Chapter 10 Modified Minimally Invasive Component Separation ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

One of the goals of minimally invasive component separation (MICS) is to avoid dissecting the subcutaneous tissue overlying the anterior rectus sheath and the vessels that penetrate the rectus abdominis muscle, thereby minimizing subcutaneous dead space and improving vascularity to the overlying skin. The inferior epigastric vessels penetrate the inferior lateral aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle and travel through the muscle, branching off into myocutaneous perforating vessels that provide vascular supply to the overlying abdominal skin and subcutaneous tissue.

One of the goals of minimally invasive component separation (MICS) is to avoid dissecting the subcutaneous tissue overlying the anterior rectus sheath and the vessels that penetrate the rectus abdominis muscle, thereby minimizing subcutaneous dead space and improving vascularity to the overlying skin. The inferior epigastric vessels penetrate the inferior lateral aspect of the rectus abdominis muscle and travel through the muscle, branching off into myocutaneous perforating vessels that provide vascular supply to the overlying abdominal skin and subcutaneous tissue. The external oblique, internal oblique, and transversalis muscles insert laterally into the rectus abdominis complex at the semilunar line. In MICS, the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle is released without disrupting much of the subcutaneous tissue attachments to the anterior rectus sheath and the rectus abdominis perforating vessels within the anterior rectus sheath. The transversalis and internal oblique musculature remains attached to the rectus complex and vascularized and innervated by the intercostal neurovascular bundles. The plane between the external and internal oblique muscle aponeuroses is relatively avascular and easily dissected to facilitate medialization of the rectus complex for the closure of moderate or large defects. Cranially, toward the costal margin, interdigitations between the external and internal oblique muscles require electrocautery dissection.

The external oblique, internal oblique, and transversalis muscles insert laterally into the rectus abdominis complex at the semilunar line. In MICS, the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle is released without disrupting much of the subcutaneous tissue attachments to the anterior rectus sheath and the rectus abdominis perforating vessels within the anterior rectus sheath. The transversalis and internal oblique musculature remains attached to the rectus complex and vascularized and innervated by the intercostal neurovascular bundles. The plane between the external and internal oblique muscle aponeuroses is relatively avascular and easily dissected to facilitate medialization of the rectus complex for the closure of moderate or large defects. Cranially, toward the costal margin, interdigitations between the external and internal oblique muscles require electrocautery dissection.2 Preoperative Considerations

Each patient’s risk for perioperative wound complications, infection, and hernia recurrence must be considered.

Each patient’s risk for perioperative wound complications, infection, and hernia recurrence must be considered. Realistic expectations of the potential outcomes must be clearly defined and discussed with each patient; topics should include the anticipated surgical outcome, possible complications, risk of recurrence, length of hospital stay, need for drainage catheters, and commitment to restrictions on activity.

Realistic expectations of the potential outcomes must be clearly defined and discussed with each patient; topics should include the anticipated surgical outcome, possible complications, risk of recurrence, length of hospital stay, need for drainage catheters, and commitment to restrictions on activity. Patients should be encouraged to cease tobacco use for at least 2 weeks before surgery. Many patients benefit from participating in nutrition and exercise programs to achieve safe weight loss before MICS for hernia repair.

Patients should be encouraged to cease tobacco use for at least 2 weeks before surgery. Many patients benefit from participating in nutrition and exercise programs to achieve safe weight loss before MICS for hernia repair.2 Musculofascial Considerations

The surgeon must consider the size and location of the defect, particularly in difficult hernia repairs in the epigastric or low suprapubic area where the possibility of medializing musculofascial tissue is limited by a lack of tissue laxity. Previous surgeries and previously placed mesh materials that have failed also must be considered. Violation of the rectus complex with stomas, stomal site hernias, port site hernias, and/or indwelling catheters also must be considered but generally are not contraindications to MICS.

The surgeon must consider the size and location of the defect, particularly in difficult hernia repairs in the epigastric or low suprapubic area where the possibility of medializing musculofascial tissue is limited by a lack of tissue laxity. Previous surgeries and previously placed mesh materials that have failed also must be considered. Violation of the rectus complex with stomas, stomal site hernias, port site hernias, and/or indwelling catheters also must be considered but generally are not contraindications to MICS. The surgeon should ascertain whether the rectus abdominis myocutaneous perforators have been elevated and ligated during previous surgeries (usually from undermining the skin flap laterally over the anterior rectus sheath). The most important musculofascial consideration is semilunar line violation. Previous musculofascial incisions and/or trauma that transected the semilunar line complicate MICS or render this procedure contraindicated on the ipsilateral side. Transverse and oblique incisions that cross the semilunar line from the oblique muscles to the rectus muscle complex are relative contraindications to performing ipsilateral MICS. Subcostal incisions, transplant incisions, and in some patients, long appendectomy scars traversing the semilunar line, may limit the extent of or preclude component separation.

The surgeon should ascertain whether the rectus abdominis myocutaneous perforators have been elevated and ligated during previous surgeries (usually from undermining the skin flap laterally over the anterior rectus sheath). The most important musculofascial consideration is semilunar line violation. Previous musculofascial incisions and/or trauma that transected the semilunar line complicate MICS or render this procedure contraindicated on the ipsilateral side. Transverse and oblique incisions that cross the semilunar line from the oblique muscles to the rectus muscle complex are relative contraindications to performing ipsilateral MICS. Subcostal incisions, transplant incisions, and in some patients, long appendectomy scars traversing the semilunar line, may limit the extent of or preclude component separation.3 Intraperitoneal (Visceral) Considerations

4 Skin Considerations

The patient should be evaluated for sufficient availability and laxity of good-quality skin to ensure reliable cutaneous closure over the musculofascial repair. Sufficient closure must be achieved to reduce the risk of skin dehiscence after surgery.

The patient should be evaluated for sufficient availability and laxity of good-quality skin to ensure reliable cutaneous closure over the musculofascial repair. Sufficient closure must be achieved to reduce the risk of skin dehiscence after surgery. The vast majority of patients have redundant, attenuated, poor-quality skin in the midline that is associated with the hernia sac. Most or all of this skin is usually resected to allow the more lateral, adequate-quality skin to be medialized and serve as the primary closure without tension.

The vast majority of patients have redundant, attenuated, poor-quality skin in the midline that is associated with the hernia sac. Most or all of this skin is usually resected to allow the more lateral, adequate-quality skin to be medialized and serve as the primary closure without tension.5 Defect Considerations

Potential bacterial contamination, including infected mesh, contamination of the surgical field, inadvertent enterotomy, existing ostomy, and/or active open-wound infection, must be considered before MICS. To reduce the risk of infection, the surgeon should aggressively debride devitalized tissue, give perioperative therapeutic antibiotics, employ pulsatile lavage, reduce subcutaneous dead space, and drain subcutaneous space with closed-suction drainage catheters.

Potential bacterial contamination, including infected mesh, contamination of the surgical field, inadvertent enterotomy, existing ostomy, and/or active open-wound infection, must be considered before MICS. To reduce the risk of infection, the surgeon should aggressively debride devitalized tissue, give perioperative therapeutic antibiotics, employ pulsatile lavage, reduce subcutaneous dead space, and drain subcutaneous space with closed-suction drainage catheters.3 Operative Steps

After making a midline incision for laparotomy, the surgeon performs adhesion lysis to mobilize all the adhesions from the dorsal aspect of the abdominal wall. The surgeon incises the musculofascia exactly at the midline of the abdomen without violating the rectus complex. The surgeon then incises the midline defect superiorly and inferiorly to combine all areas of midline herniation into a single defect. In patients who have had previous surgeries, the surgeon should palpate intraperitoneally any areas of unopened midline incisions to identify sites possibly subject to future herniation. At this time, any planned or unplanned intraperitoneal or intrapelvic surgeries should be performed before MICS.

After making a midline incision for laparotomy, the surgeon performs adhesion lysis to mobilize all the adhesions from the dorsal aspect of the abdominal wall. The surgeon incises the musculofascia exactly at the midline of the abdomen without violating the rectus complex. The surgeon then incises the midline defect superiorly and inferiorly to combine all areas of midline herniation into a single defect. In patients who have had previous surgeries, the surgeon should palpate intraperitoneally any areas of unopened midline incisions to identify sites possibly subject to future herniation. At this time, any planned or unplanned intraperitoneal or intrapelvic surgeries should be performed before MICS. The surgeon dissects preperitoneal fat from the posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle complex to facilitate the direct placement of implantable surgical mesh to the posterior rectus sheath. The majority of the preperitoneal fat pad is generally located in the central portion of the abdominal wall near the linea alba and is more extensive, thicker, and wider near the costal margin and the pubis than in the central, periumbilical area. Dissecting the preperitoneal fat pad flap at least 5 cm in the most cranial and caudal aspects of the defect facilitates mesh implantation. Patients with numerous previous surgeries and patients with a very thin body habitus may not have a well-defined preperitoneal fat layer. After adhesion lysis and preperitoneal flap dissection has been completed, the surgeon should place a moist, radiopaque-tagged towel or sponge on the intraperitoneal viscera to help protect it from inadvertent trauma and dissection.

The surgeon dissects preperitoneal fat from the posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle complex to facilitate the direct placement of implantable surgical mesh to the posterior rectus sheath. The majority of the preperitoneal fat pad is generally located in the central portion of the abdominal wall near the linea alba and is more extensive, thicker, and wider near the costal margin and the pubis than in the central, periumbilical area. Dissecting the preperitoneal fat pad flap at least 5 cm in the most cranial and caudal aspects of the defect facilitates mesh implantation. Patients with numerous previous surgeries and patients with a very thin body habitus may not have a well-defined preperitoneal fat layer. After adhesion lysis and preperitoneal flap dissection has been completed, the surgeon should place a moist, radiopaque-tagged towel or sponge on the intraperitoneal viscera to help protect it from inadvertent trauma and dissection. Surgeons may choose to place mesh in the retrorectus rather than the preperitoneal plane, particularly if macroporous, synthetic mesh will be used. This minimizes mesh exposure directly to abdominal viscera. The retrorectus plane is developed by incising the posterior rectus sheath just lateral to the linea alba and dissecting between the rectus abdominis muscle and posterior rectus sheath. Below the arcuate line, where there is no posterior rectus sheath, the preperitoneal fat pad can be elevated in continuity. After MICS is completed and before insetting mesh to the semilunar lines, the posterior sheath and preperitoneal fat pad from each side are closed in the midline, thereby separating the intraperitoneal contents from the mesh.

Surgeons may choose to place mesh in the retrorectus rather than the preperitoneal plane, particularly if macroporous, synthetic mesh will be used. This minimizes mesh exposure directly to abdominal viscera. The retrorectus plane is developed by incising the posterior rectus sheath just lateral to the linea alba and dissecting between the rectus abdominis muscle and posterior rectus sheath. Below the arcuate line, where there is no posterior rectus sheath, the preperitoneal fat pad can be elevated in continuity. After MICS is completed and before insetting mesh to the semilunar lines, the posterior sheath and preperitoneal fat pad from each side are closed in the midline, thereby separating the intraperitoneal contents from the mesh. To facilitate suture placement for insetting implantable surgical mesh and fascial closure, the surgeon dissects the subcutaneous tissue from the anterior rectus sheath approximately 2 to 4 cm circumferentially. The dissection should extend laterally to the medial row of the rectus abdominis myofascial perforators, which is preserved.

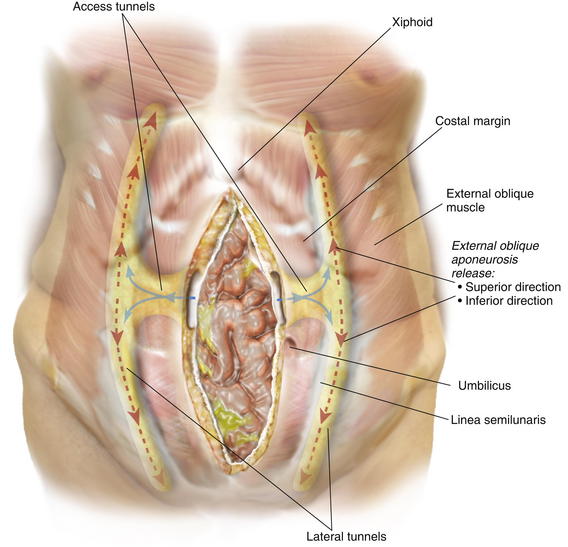

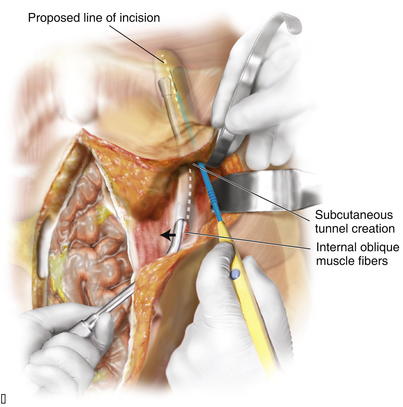

To facilitate suture placement for insetting implantable surgical mesh and fascial closure, the surgeon dissects the subcutaneous tissue from the anterior rectus sheath approximately 2 to 4 cm circumferentially. The dissection should extend laterally to the medial row of the rectus abdominis myofascial perforators, which is preserved. Depending on the length of the defect and body habitus of the patient, the surgeon accesses the semilunar line through one or two narrow tunnel incisions between the anterior rectus fascia and subcutaneous tissue. The hernia sac, which typically extends laterally towards the semilunar line, is often used to initiate tunnel access. Generally, a single tunnel incision is used in the supraumbilical area centered between the umbilicus and the costal margin. A narrow Deaver retractor is used to elevate the subcutaneous tissue, and electrocautery is used to dissect an approximately 4-cm-wide tunnel laterally to approximately 2 cm lateral to the semilunar line (Fig. 10-1). These lateral access tunnels allow creation of vertically oriented subcutaneous lateral tunnels over the anticipated external oblique aponeurosis release sites (depicted in Fig. 10-1) later in the procedure.

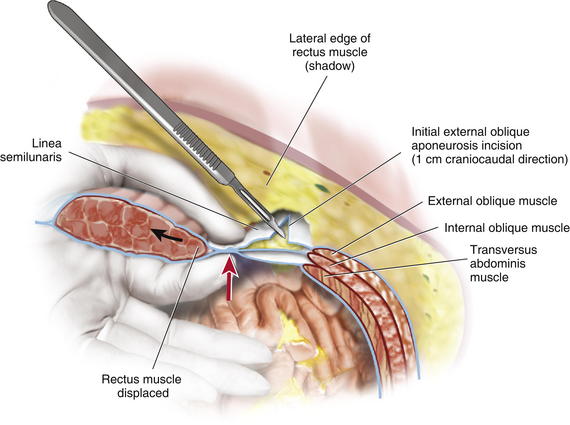

Depending on the length of the defect and body habitus of the patient, the surgeon accesses the semilunar line through one or two narrow tunnel incisions between the anterior rectus fascia and subcutaneous tissue. The hernia sac, which typically extends laterally towards the semilunar line, is often used to initiate tunnel access. Generally, a single tunnel incision is used in the supraumbilical area centered between the umbilicus and the costal margin. A narrow Deaver retractor is used to elevate the subcutaneous tissue, and electrocautery is used to dissect an approximately 4-cm-wide tunnel laterally to approximately 2 cm lateral to the semilunar line (Fig. 10-1). These lateral access tunnels allow creation of vertically oriented subcutaneous lateral tunnels over the anticipated external oblique aponeurosis release sites (depicted in Fig. 10-1) later in the procedure. It is imperative to identify the semilunar line to ensure that the appropriate plane is entered for the component separation release. Palpation is used to identify the edge of the rectus muscle, lateral edge of the rectus sheath, and transition of oblique musculature to aponeurosis, which serve as landmarks (Fig. 10-2). The presence of a fat pad between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses is a good indication of being in the correct plane. The optimal location of the release of the external oblique muscle is through its aponeurosis medial to the muscle body and lateral to its insertion into the rectus sheath complex, that is, generally 1.5 cm lateral to the lateral edge of the rectus complex. The area is marked with a pen and incised with a scalpel or electrocautery for 1 cm in the craniocaudal direction (see Fig. 10-2). In the event that the incision enters the rectus sheath (revealing the rectus abdominis muscle), the incision is closed and a new incision is made more laterally.

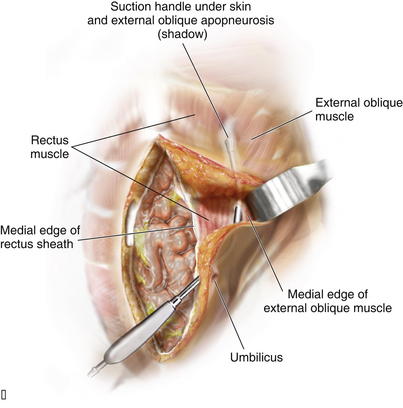

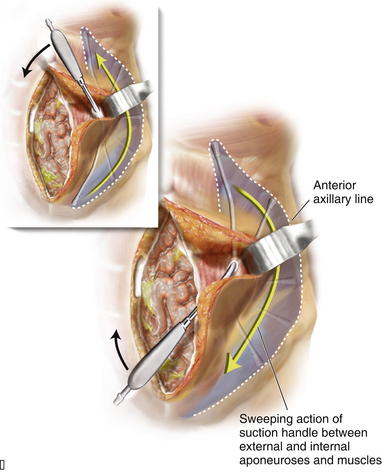

It is imperative to identify the semilunar line to ensure that the appropriate plane is entered for the component separation release. Palpation is used to identify the edge of the rectus muscle, lateral edge of the rectus sheath, and transition of oblique musculature to aponeurosis, which serve as landmarks (Fig. 10-2). The presence of a fat pad between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses is a good indication of being in the correct plane. The optimal location of the release of the external oblique muscle is through its aponeurosis medial to the muscle body and lateral to its insertion into the rectus sheath complex, that is, generally 1.5 cm lateral to the lateral edge of the rectus complex. The area is marked with a pen and incised with a scalpel or electrocautery for 1 cm in the craniocaudal direction (see Fig. 10-2). In the event that the incision enters the rectus sheath (revealing the rectus abdominis muscle), the incision is closed and a new incision is made more laterally. Blunt dissection between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses and muscle is performed through the 1-cm vertical incision in the external oblique aponeurosis. The surgeon uses a blunt-tip, metal Yankauer suction handle (not connected to suction) to start the dissection between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses inferiorly and superiorly to the initial external oblique aponeurosis incision (Fig. 10-3). This should slide easily just lateral to the rectus complex superiorly over the costal margin (shown) and inferiorly toward the pubis (not shown). This sweeping blunt dissection provides separation between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses for a safe separation of the external oblique aponeurosis in a minimally invasive fashion without inadvertent injury to the underlying internal oblique structure muscular aponeurosis. The surgeon then inserts the suction handle inferiorly between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses and positions the handle against the rectus abdominis muscle complex and uses the suction handle as a palpable guide to create vertical, 3-cm-wide, subcutaneous tunnels (Fig. 10-4, A). Using a narrow Deaver retractor and electrocautery, dissection over the external oblique aponeurosis release site is performed inferiorly and superiorly (see Fig. 10-4). The external oblique aponeurosis is then freed anteriorly and posteriorly and can be easily transected without injuring the overlying subcutaneous tissue or underlying oblique muscle or aponeurosis.

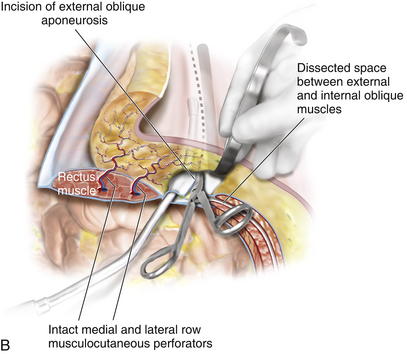

Blunt dissection between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses and muscle is performed through the 1-cm vertical incision in the external oblique aponeurosis. The surgeon uses a blunt-tip, metal Yankauer suction handle (not connected to suction) to start the dissection between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses inferiorly and superiorly to the initial external oblique aponeurosis incision (Fig. 10-3). This should slide easily just lateral to the rectus complex superiorly over the costal margin (shown) and inferiorly toward the pubis (not shown). This sweeping blunt dissection provides separation between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses for a safe separation of the external oblique aponeurosis in a minimally invasive fashion without inadvertent injury to the underlying internal oblique structure muscular aponeurosis. The surgeon then inserts the suction handle inferiorly between the internal and external oblique aponeuroses and positions the handle against the rectus abdominis muscle complex and uses the suction handle as a palpable guide to create vertical, 3-cm-wide, subcutaneous tunnels (Fig. 10-4, A). Using a narrow Deaver retractor and electrocautery, dissection over the external oblique aponeurosis release site is performed inferiorly and superiorly (see Fig. 10-4). The external oblique aponeurosis is then freed anteriorly and posteriorly and can be easily transected without injuring the overlying subcutaneous tissue or underlying oblique muscle or aponeurosis. The external oblique aponeurosis incision can be performed inferiorly and superiorly to the initial external oblique aponeurosis incision through the initial lateral tunnel incision. The blunt tip suction handle is again used as a guide to avoid inadvertently entering the rectus complex medially (Fig. 10-4, B). The surgeon uses scissors to release the inferior half of the external oblique aponeurosis, which extends towards the pubis. The same technique is applied superiorly to fully release the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle; however, electrocautery becomes necessary as more muscle and less aponeurosis are present at and above the costal margin. The release is continued cranially to 8-12 cm cranial to the costal margin. Electrocautery for hemostasis and dissection is often required for the considerable interdigitation between the external oblique muscular aponeurosis and the underlying musculature at and above the costal margin. After the external oblique aponeurosis is completely released, the internal oblique muscle should be clearly visible.

The external oblique aponeurosis incision can be performed inferiorly and superiorly to the initial external oblique aponeurosis incision through the initial lateral tunnel incision. The blunt tip suction handle is again used as a guide to avoid inadvertently entering the rectus complex medially (Fig. 10-4, B). The surgeon uses scissors to release the inferior half of the external oblique aponeurosis, which extends towards the pubis. The same technique is applied superiorly to fully release the aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle; however, electrocautery becomes necessary as more muscle and less aponeurosis are present at and above the costal margin. The release is continued cranially to 8-12 cm cranial to the costal margin. Electrocautery for hemostasis and dissection is often required for the considerable interdigitation between the external oblique muscular aponeurosis and the underlying musculature at and above the costal margin. After the external oblique aponeurosis is completely released, the internal oblique muscle should be clearly visible. Sharp and electrocautery dissection between the internal and external oblique muscles should be completed through the initial lateral tunnel incision. Narrow Deaver retractors and a headlight or lighted retractor are helpful in performing this maneuver. The lateral extent of the dissection between the internal and external oblique muscles continues laterally to the anterior axillary line to facilitate maximal medialization of the rectus complex. The surgeon must avoid injuring the underlying internal oblique muscle and aponeurosis, which can cause potential weakness or herniation.

Sharp and electrocautery dissection between the internal and external oblique muscles should be completed through the initial lateral tunnel incision. Narrow Deaver retractors and a headlight or lighted retractor are helpful in performing this maneuver. The lateral extent of the dissection between the internal and external oblique muscles continues laterally to the anterior axillary line to facilitate maximal medialization of the rectus complex. The surgeon must avoid injuring the underlying internal oblique muscle and aponeurosis, which can cause potential weakness or herniation. After the minimally invasive release on one side is complete, a medialization of the rectus complex and overlying attached soft tissue should be visible. If additional access to the semilunar line is required, the surgeon can perform a second tunnel incision 10 to 15 cm inferior to the initial tunnel incision. The entire procedure is then performed identically on the contralateral side.

After the minimally invasive release on one side is complete, a medialization of the rectus complex and overlying attached soft tissue should be visible. If additional access to the semilunar line is required, the surgeon can perform a second tunnel incision 10 to 15 cm inferior to the initial tunnel incision. The entire procedure is then performed identically on the contralateral side. To determine whether primary fascial midline closure is possible, the surgeon places Kocher clamps on the fascial edge and retracts the fascial edges toward the midline. Inlay mesh is used to reinforce the primary fascial closure. If primary fascial closure is not possible in all or some areas of the defect, an inlay-bridging mesh is required.

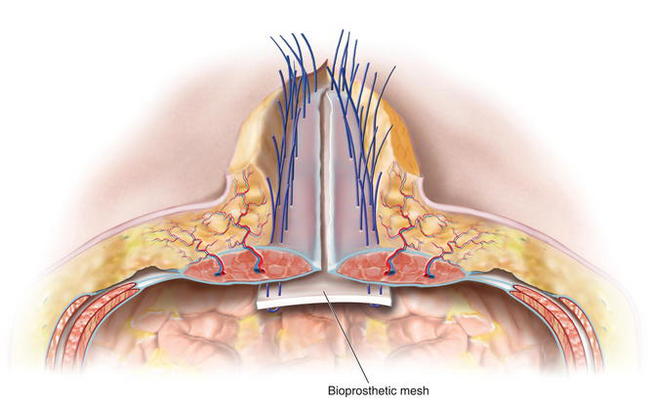

To determine whether primary fascial midline closure is possible, the surgeon places Kocher clamps on the fascial edge and retracts the fascial edges toward the midline. Inlay mesh is used to reinforce the primary fascial closure. If primary fascial closure is not possible in all or some areas of the defect, an inlay-bridging mesh is required. The defect’s condition and the surgeon’s preferences determine the type of implantable surgical mesh to be used. To avoid the consequences of adhesions, macroporous synthetic mesh should not be placed directly onto the intraperitoneal viscera. Instead, for simple defects, composite antiadhesive barrier mesh may be used. For complex defects, particularly defects with bacterial contamination, defects in which mesh may be placed directly over viscera, defects with a high risk of skin dehiscence with subsequent mesh exposure, and/or defects in patients at an increased risk for perioperative wound healing complications, bioprosthetic mesh is generally used. The procedure has been described by the author, Charles Butler, as the MICSIB (Minimally Invasive Component Separation with Inlay Bioprosthetic Mesh) technique when minimally invasive component separation is used with an inlay bioprosthetic mesh. The mesh is inset with at least 4-5 cms of overlap with the musculofascial edges to ensure a reliable repair. The surgeon cuts the mesh, orients it into the defect, and marks the midline of the mesh with a marker. The surgeon then resects any devitalized, attenuated, or severely scarred midline tissue. The surgeon marks the anticipated suture line on the mesh and the musculofascia to ensure that once the inset sutures have been placed and tied, the fascial edges meet at the midline without tension over the reinforcing mesh inlay if primary fascial closure is possible (reinforced repair). If bridging mesh is required, the surgeon marks the area of bridging and the anticipated positions of central suture lines where the true musculofascial edges are inset to the mesh.

The defect’s condition and the surgeon’s preferences determine the type of implantable surgical mesh to be used. To avoid the consequences of adhesions, macroporous synthetic mesh should not be placed directly onto the intraperitoneal viscera. Instead, for simple defects, composite antiadhesive barrier mesh may be used. For complex defects, particularly defects with bacterial contamination, defects in which mesh may be placed directly over viscera, defects with a high risk of skin dehiscence with subsequent mesh exposure, and/or defects in patients at an increased risk for perioperative wound healing complications, bioprosthetic mesh is generally used. The procedure has been described by the author, Charles Butler, as the MICSIB (Minimally Invasive Component Separation with Inlay Bioprosthetic Mesh) technique when minimally invasive component separation is used with an inlay bioprosthetic mesh. The mesh is inset with at least 4-5 cms of overlap with the musculofascial edges to ensure a reliable repair. The surgeon cuts the mesh, orients it into the defect, and marks the midline of the mesh with a marker. The surgeon then resects any devitalized, attenuated, or severely scarred midline tissue. The surgeon marks the anticipated suture line on the mesh and the musculofascia to ensure that once the inset sutures have been placed and tied, the fascial edges meet at the midline without tension over the reinforcing mesh inlay if primary fascial closure is possible (reinforced repair). If bridging mesh is required, the surgeon marks the area of bridging and the anticipated positions of central suture lines where the true musculofascial edges are inset to the mesh. The surgeon then performs a circumferential, interrupted #1 polypropylene suture inlay inset through the full thickness of the musculofascia, through the mesh, and then back out through the musculofascia. In Figure 10-5 the separation of the internal and external oblique muscles laterally and the completed external oblique aponeurosis release are shown with the discontinued external oblique aponeurosis on both sides. The rectus complex on both sides is now able to be medialized toward the midline. Bioprosthetic mesh is being inset with interrupted monofilament sutures. Suture knots are oriented ventral to the musculofascia. The distance between the entry and exit of a suture through the fascia should be at least 1.5 cm to avoid suture pull-through and sutures should be placed at approximately 2-cm intervals on the musculofascia during the inset. The most superior suture is placed first, often through or around the xiphoid process, and the remainder of the costal margin inset is performed with all sutures placed on hemostats and left untied. Next, the most inferior suture is placed to provide midline orientation and establish the appropriate physiologic tension of the inlay mesh. The remaining sutures are then placed in the appropriate positions to enable primary fascial closure (reinforced repair) or placement of bridging mesh (bridged repair) as previously determined. The surgeon must identify the inferior epigastric vessels as they penetrate the rectus muscles to avoid inadvertently occluding them with a suture and thereby compromising the vascularity of the rectus complex and overlying skin.

The surgeon then performs a circumferential, interrupted #1 polypropylene suture inlay inset through the full thickness of the musculofascia, through the mesh, and then back out through the musculofascia. In Figure 10-5 the separation of the internal and external oblique muscles laterally and the completed external oblique aponeurosis release are shown with the discontinued external oblique aponeurosis on both sides. The rectus complex on both sides is now able to be medialized toward the midline. Bioprosthetic mesh is being inset with interrupted monofilament sutures. Suture knots are oriented ventral to the musculofascia. The distance between the entry and exit of a suture through the fascia should be at least 1.5 cm to avoid suture pull-through and sutures should be placed at approximately 2-cm intervals on the musculofascia during the inset. The most superior suture is placed first, often through or around the xiphoid process, and the remainder of the costal margin inset is performed with all sutures placed on hemostats and left untied. Next, the most inferior suture is placed to provide midline orientation and establish the appropriate physiologic tension of the inlay mesh. The remaining sutures are then placed in the appropriate positions to enable primary fascial closure (reinforced repair) or placement of bridging mesh (bridged repair) as previously determined. The surgeon must identify the inferior epigastric vessels as they penetrate the rectus muscles to avoid inadvertently occluding them with a suture and thereby compromising the vascularity of the rectus complex and overlying skin. Once all inset sutures are placed and tagged with hemostats, the surgeon applies tension to them to confirm that the physiologic tension of the inset mesh will be appropriate and ensure that primary fascial closure is possible. The inset sutures are then individually tied under tension with the adjacent sutures above and below the placed on tension to facilitate an appropriate inset tension of the suture being tied. The surgeon should carefully visually inspect the intraperitoneal space and manually palpate each suture to ensure that any inclusion of intraperitoneal viscera within the suture loops has not occurred. After tying the inset sutures, the surgeon places a closed-suction drainage catheter to remove fluid from the space between the inset mesh and the overlying musculofascial closure.

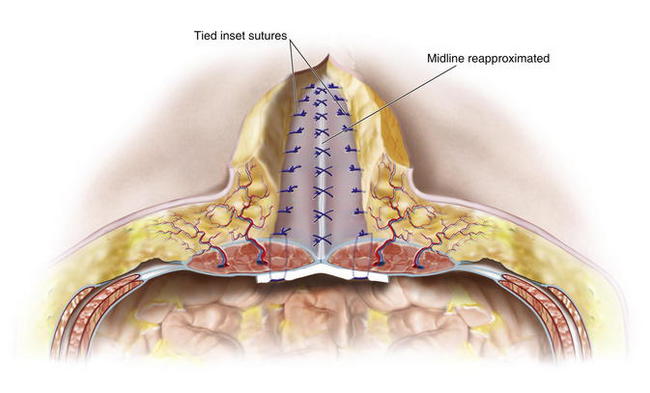

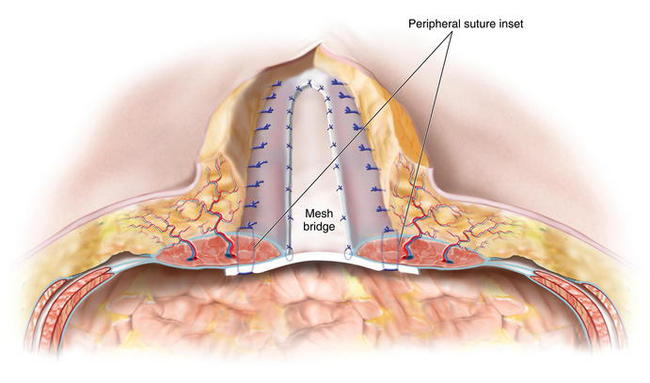

Once all inset sutures are placed and tagged with hemostats, the surgeon applies tension to them to confirm that the physiologic tension of the inset mesh will be appropriate and ensure that primary fascial closure is possible. The inset sutures are then individually tied under tension with the adjacent sutures above and below the placed on tension to facilitate an appropriate inset tension of the suture being tied. The surgeon should carefully visually inspect the intraperitoneal space and manually palpate each suture to ensure that any inclusion of intraperitoneal viscera within the suture loops has not occurred. After tying the inset sutures, the surgeon places a closed-suction drainage catheter to remove fluid from the space between the inset mesh and the overlying musculofascial closure. When complete primary fascial closure is planned, the surgeon reapproximates the fascial edges in the midline with either a running or interrupted long-term monofilament resorbable suture (Fig. 10-6). The vascularity of the rectus muscle is then assessed to ensure that it has not become congested or devascularized after inset placement. In areas where bridging is required and primary fascial reapproximation at the midline is not possible, the surgeon should use resorbable sutures to carefully tack the fascial edges to the surface of the mesh without injuring the underlying intraperitoneal structures (Fig. 10-7). To protect from inadvertent injury to intraperitoneal sutures while placing these central sutures, it is helpful to have left several peripheral inset sutures untied and placed on hemostats. A wide malleable retractor (not shown in Fig. 10-7) can be inserted through this area and placed just under the bioprosthetic mesh to protect the bowel during central inset suture placement. The few untied inset sutures are then tied.

When complete primary fascial closure is planned, the surgeon reapproximates the fascial edges in the midline with either a running or interrupted long-term monofilament resorbable suture (Fig. 10-6). The vascularity of the rectus muscle is then assessed to ensure that it has not become congested or devascularized after inset placement. In areas where bridging is required and primary fascial reapproximation at the midline is not possible, the surgeon should use resorbable sutures to carefully tack the fascial edges to the surface of the mesh without injuring the underlying intraperitoneal structures (Fig. 10-7). To protect from inadvertent injury to intraperitoneal sutures while placing these central sutures, it is helpful to have left several peripheral inset sutures untied and placed on hemostats. A wide malleable retractor (not shown in Fig. 10-7) can be inserted through this area and placed just under the bioprosthetic mesh to protect the bowel during central inset suture placement. The few untied inset sutures are then tied. The surgeon then carefully measures the amount of skin redundancy for a vertically oriented central skin and subcutaneous tissue resection, which is performed to minimize dead space and to remove central, less vascularized tissue.

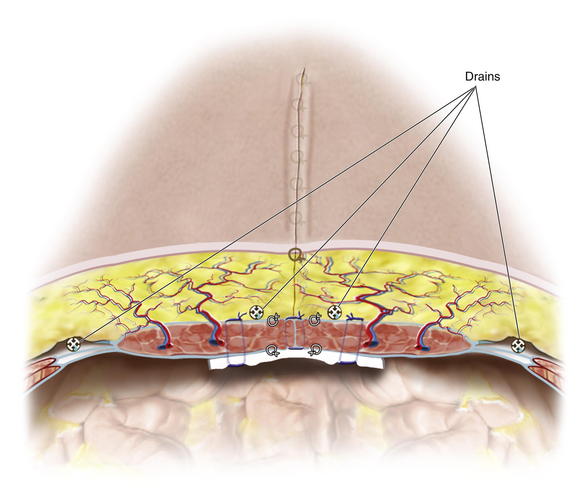

The surgeon then carefully measures the amount of skin redundancy for a vertically oriented central skin and subcutaneous tissue resection, which is performed to minimize dead space and to remove central, less vascularized tissue. Large-bore, round, channeled, closed-suction drainage catheters are placed with the drains exiting the suprapubic area. One drain is placed laterally in each MICS donor site, and depending on the volume of subcutaneous space, two to five drains are placed centrally in the subcutaneous space.

Large-bore, round, channeled, closed-suction drainage catheters are placed with the drains exiting the suprapubic area. One drain is placed laterally in each MICS donor site, and depending on the volume of subcutaneous space, two to five drains are placed centrally in the subcutaneous space. Generally, 3 to 5 interrupted 3-0 resorbable sutures are placed in a vertical line between drainage catheter channels to quilt the elevated skin flaps from Scarpa fascia to the musculofascial repair to eliminate dead space and reduce shear. Figure 10-8 shows a completed closure in three-dimensional cross section, indicating location of drainage catheters inset sutures, and quilting sutures. This technique has minimized the need for extensive skin flap elevation and preserved the rectus perforator vascularity to the overlying skin.

Generally, 3 to 5 interrupted 3-0 resorbable sutures are placed in a vertical line between drainage catheter channels to quilt the elevated skin flaps from Scarpa fascia to the musculofascial repair to eliminate dead space and reduce shear. Figure 10-8 shows a completed closure in three-dimensional cross section, indicating location of drainage catheters inset sutures, and quilting sutures. This technique has minimized the need for extensive skin flap elevation and preserved the rectus perforator vascularity to the overlying skin.4 Postoperative Care

Patients are generally hospitalized for 3 to 6 days after MICS, depending on the complexity of the reconstruction and whether other intraabdominal procedures were performed.

Patients are generally hospitalized for 3 to 6 days after MICS, depending on the complexity of the reconstruction and whether other intraabdominal procedures were performed. Patients are encouraged to walk either the day of surgery or the following morning. Depending on a patient’s risk factors, an anticoagulant may be prescribed to prevent venous thromboembolism.

Patients are encouraged to walk either the day of surgery or the following morning. Depending on a patient’s risk factors, an anticoagulant may be prescribed to prevent venous thromboembolism. Perioperative antibiotics are discontinued within 24 hours of surgery unless indicated to treat an existing contamination and/or infection. Pain control is generally managed with an epidural catheter until the patient can tolerate oral narcotics.

Perioperative antibiotics are discontinued within 24 hours of surgery unless indicated to treat an existing contamination and/or infection. Pain control is generally managed with an epidural catheter until the patient can tolerate oral narcotics. Oral diet is advanced gradually as tolerated, generally starting with sips of clear fluid the morning after surgery.

Oral diet is advanced gradually as tolerated, generally starting with sips of clear fluid the morning after surgery.5 Pearls/Pitfalls

Surgeons must actively manage patients’ expectations before patients undergo MICS. Patients must understand that MICS is a complex procedure, that indwelling drainage catheters will be present after surgery, that the umbilicus may be resected, that they may experience pain after surgery, that they must restrict their activity after surgery, and that complications can occur.

Surgeons must actively manage patients’ expectations before patients undergo MICS. Patients must understand that MICS is a complex procedure, that indwelling drainage catheters will be present after surgery, that the umbilicus may be resected, that they may experience pain after surgery, that they must restrict their activity after surgery, and that complications can occur. Meticulous attention to detail during tissue dissection, component separation release, and mesh inset is critical to the success of MICS. The appropriate physiologic tension of the mesh inset must be achieved to reduce the risk of bulge and/or early hernia recurrence (tear) owing to insets that are too loose or too tight, respectively.

Meticulous attention to detail during tissue dissection, component separation release, and mesh inset is critical to the success of MICS. The appropriate physiologic tension of the mesh inset must be achieved to reduce the risk of bulge and/or early hernia recurrence (tear) owing to insets that are too loose or too tight, respectively. Eliminating dead space reduces the risk of potentially chronic and/or infected subcutaneous and retrorectus fluid collections. To help reduce the risk of fluid collection, the surgeon should place drainage catheters and use quilting sutures.

Eliminating dead space reduces the risk of potentially chronic and/or infected subcutaneous and retrorectus fluid collections. To help reduce the risk of fluid collection, the surgeon should place drainage catheters and use quilting sutures. The vascularity of the rectus abdominis muscle must be confirmed during and after mesh inset. If venous congestion or arterial insufficiency of the muscle is suspected, the surgeon should evaluate the sutures to ensure that the inferior epigastric pedicle has not been inadvertently included within a suture and that the sutures have not been placed too close together laterally, which could devascularize the central rectus muscle. In some patients, a posterior sheath release approximately 2 cm lateral to the midline can reduce vascular congestion, particularly if the congestion is related to rectus sheath constriction.

The vascularity of the rectus abdominis muscle must be confirmed during and after mesh inset. If venous congestion or arterial insufficiency of the muscle is suspected, the surgeon should evaluate the sutures to ensure that the inferior epigastric pedicle has not been inadvertently included within a suture and that the sutures have not been placed too close together laterally, which could devascularize the central rectus muscle. In some patients, a posterior sheath release approximately 2 cm lateral to the midline can reduce vascular congestion, particularly if the congestion is related to rectus sheath constriction. The appropriate number of mesh inset sutures must be placed at the proper intervals. Too few sutures or too long an interval between consecutive sutures may result in herniation and/or insufficient mechanical strength to withstand the forces of the abdominal wall musculature. Too many sutures or too small an interval between consecutive sutures may compromise the vascularity of the central rectus complex, potentially leading to poor wound healing, musculofascial necrosis, and subsequent failure of the defect repair.

The appropriate number of mesh inset sutures must be placed at the proper intervals. Too few sutures or too long an interval between consecutive sutures may result in herniation and/or insufficient mechanical strength to withstand the forces of the abdominal wall musculature. Too many sutures or too small an interval between consecutive sutures may compromise the vascularity of the central rectus complex, potentially leading to poor wound healing, musculofascial necrosis, and subsequent failure of the defect repair. The surgeon should perform a complete release of the musculature from near the pubis to superior to the costal margin to enable maximal medialization of the rectus complex. The surgeon also should perform a complete dissection between the internal and external oblique muscles to the lateral axillary line. Together, these two maneuvers facilitate the primary fascial closure of very large defects in the epigastric region without undue tension.

The surgeon should perform a complete release of the musculature from near the pubis to superior to the costal margin to enable maximal medialization of the rectus complex. The surgeon also should perform a complete dissection between the internal and external oblique muscles to the lateral axillary line. Together, these two maneuvers facilitate the primary fascial closure of very large defects in the epigastric region without undue tension.Baumann DP, Butler CE: Abdominal wall wounds. In Marsh J, Perlyn C, editors: Decision-Making in Plastic Surgery. St. Louis, MO: Quality Medical Publishing, In Press.

Breuing K., Butler C.E., Ferzoco S., Franz M., Hultman C.S., Kilbridge J.F., Rosen M., Silverman R.P., Vargo D. Incisional ventral hernias: review of the literature and recommendations regarding the grading and technique of repair. Surgery. Epub ahead of print. March 19, 2010. In Press

Butler C.E. Ciné Clinic I: Plastic Surgery: Minimally invasive component separation with inlay bioprosthetic mesh (MICSIB). October 13. American College of Surgeons 94th Annual Clinical Congress, San Francisco, CA, 2008.

Butler C.E., Langstein H.N., Kronowitz S.J. Pelvic, abdominal, and chest wall reconstruction with AlloDerm in patients at increased risk for mesh-related complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1263-1275.

Campbell K, Butler CE. Minimally Invasive Component Separation with Inlay Bioprosthetic Mesh (MICSIB) for Complex Abdominal Wall Reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. In Press.