Mobilization and Exercise

Testing and Training

This chapter describes the principles and practices for exploiting the preventive, acute, and long-term effects of mobilization, exercise, and training. Mobilization and exercise are prescribed to elicit whichever of these distinct effects is indicated. They are prescribed on the basis of their indications, contraindications, and potential side effects for a given individual. Exercise to exploit each of these effects can be prescribed to address limitations in specific organ systems, as well as augment activity ability and participation. Chapters 24 and 25 expand on these topics, describing special considerations for patient populations with an emphasis on targeting exercise testing and prescription for training based on people with conditions rather than for the condition(s) a patient has.

Pre-exercise Test Evaluation

Pre-exercise Screening for Minimizing Cardiovascular Risk During Testing

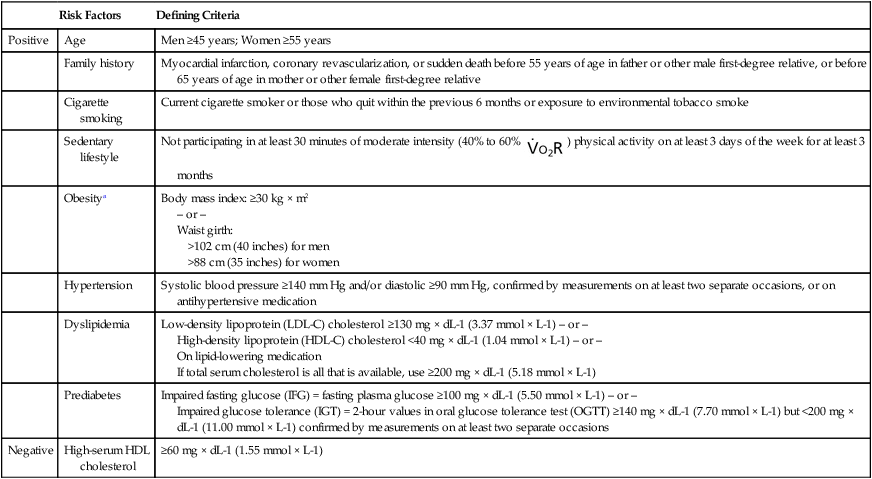

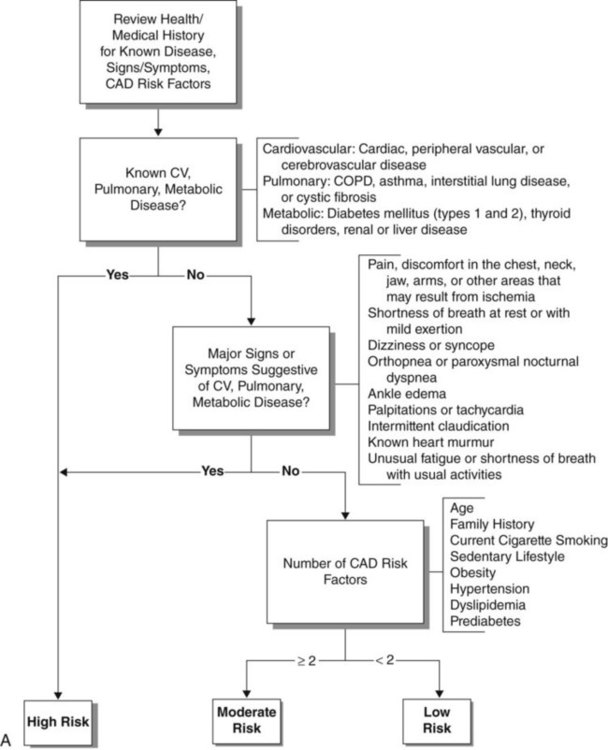

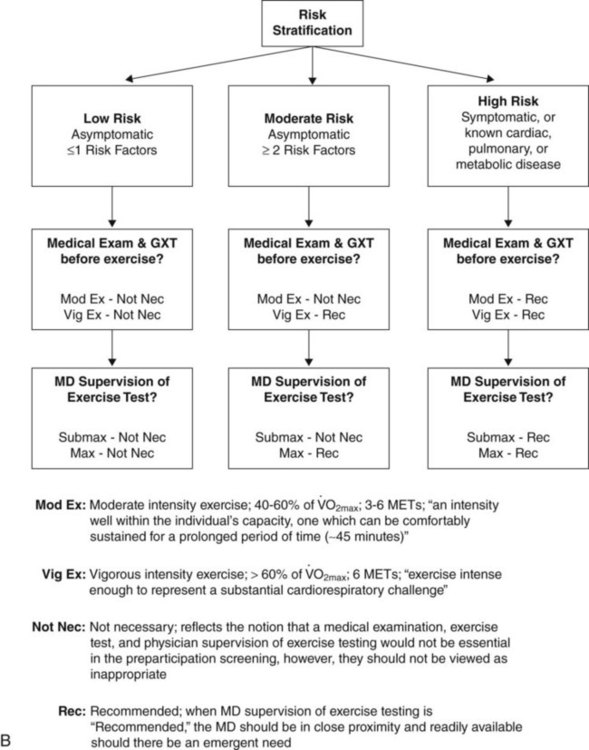

Exercise testing can pose a risk to the patient, so exercise testing must have clear indications, and any contraindications must be ruled out. On the other hand, earlier guidelines for exercise testing in patients, particularly those with cardiac conditions, were too conservative.1 Patients can be exercised aggressively provided that the indications are based on a comprehensive assessment and a judiciously selected exercise test and protocol and provided that the patient is appropriately monitored throughout testing. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)2 has developed an algorithm (Figure 19-1, A) to determine the risk for cardiovascular events during exercise testing (Table 19-1) as well as guidelines for test selection and level of supervision required based on the risk assessment (Figure 19-1, B). As shown in Figure 19-1, A, patients with known cardiovascular, metabolic, or pulmonary disease are classified as having a high risk for sustaining a cardiovascular event during exercise. For these individuals, a comprehensive medical examination and physician-supervised exercise testing is recommended before starting a moderate or vigorous intensity exercise program (see Figure 19-1, B). For individuals who do not have the conditions listed above, the remainder of the algorithm describes how patient signs and symptoms and coronary artery disease risk factors determine the risk classification and exercise testing and supervision requirements. Physical therapists need to screen patients systematically before exercise testing or prescription.

Table 19-1

Cardiovascular Risk Factor Threshold for Risk Stratification

| Risk Factors | Defining Criteria | |

| Positive | Age | Men ≥45 years; Women ≥55 years |

| Family history | Myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, or sudden death before 55 years of age in father or other male first-degree relative, or before 65 years of age in mother or other female first-degree relative | |

| Cigarette smoking | Current cigarette smoker or those who quit within the previous 6 months or exposure to environmental tobacco smoke | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | Not participating in at least 30 minutes of moderate intensity (40% to 60%  ) physical activity on at least 3 days of the week for at least 3 months ) physical activity on at least 3 days of the week for at least 3 months |

|

| Obesitya | Body mass index: ≥30 kg × m2 – or – Waist girth: >102 cm (40 inches) for men >88 cm (35 inches) for women |

|

| Hypertension | Systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic ≥90 mm Hg, confirmed by measurements on at least two separate occasions, or on antihypertensive medication | |

| Dyslipidemia | Low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C) cholesterol ≥130 mg × dL-1 (3.37 mmol × L-1) – or – High-density lipoprotein (HDL-C) cholesterol <40 mg × dL-1 (1.04 mmol × L-1) – or – On lipid-lowering medication If total serum cholesterol is all that is available, use ≥200 mg × dL-1 (5.18 mmol × L-1) |

|

| Prediabetes | Impaired fasting glucose (IFG) = fasting plasma glucose ≥100 mg × dL-1 (5.50 mmol × L-1) – or – Impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) = 2-hour values in oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) ≥140 mg × dL-1 (7.70 mmol × L-1) but <200 mg × dL-1 (11.00 mmol × L-1) confirmed by measurements on at least two separate occasions |

|

| Negative | High-serum HDL cholesterol | ≥60 mg × dL-1 (1.55 mmol × L-1) |

aProfessional opinions vary regarding the most appropriate markers and thresholds for obesity; therefore allied health professionals should use clinical judgment when evaluating the risk factor.

Modified from the American College of Sports Medicine. (2010). Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, ed 8. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins.

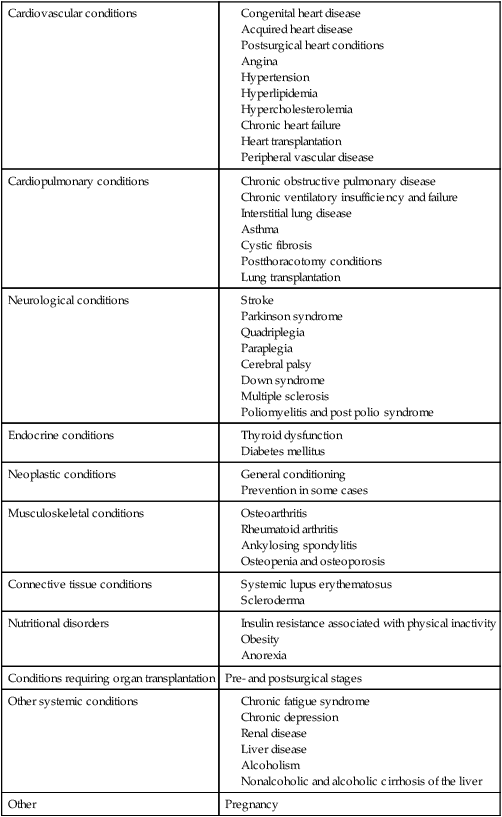

Exercise Testing

Numerous conditions, including nonprimary cardiovascular and pulmonary conditions, have been shown to benefit from the long-term effects of aerobic exercise (Table 19-2) (see Chapters 24 and 25). Thus for each patient with these conditions, the exercise prescription differs. Comparable with prescribing mobilization in acute conditions, prescribing exercise for long-term adaptations is based on the patient’s presentation, history, premorbid status and conditioning level, lab and investigative reports related to physiological reserve capacity, the exercise test, and the goals of the exercise prescription. To promote health, as few as 30 minutes of moderately intense exercise a day on most days of the week is required.3 However, based on ACSM (2010)2 guidelines, optimal aerobic exercise adaptation requires an exercise stimulus of 70% to 85% of HRmax for 20 to 40 minutes, 3 to 5 times a week for at least 6 to 8 weeks. However, the effect of exercise intensity on  and on CO continues to be studied.4 Improvement in

and on CO continues to be studied.4 Improvement in  does not appear to be achieved by the same central and peripheral adaptations across a range of exercise intensities. Some individuals have high

does not appear to be achieved by the same central and peripheral adaptations across a range of exercise intensities. Some individuals have high  , CO, and SV without a history of training.5 This may reflect a genetically determined greater blood volume.

, CO, and SV without a history of training.5 This may reflect a genetically determined greater blood volume.

The indications for exercise testing are numerous (Box 19-1). They range from quantifying maximum functional, aerobic, or oxygen transport capacities to assessing endurance during low-level activities of daily living (ADLs). The capacity of the oxygen transport system is the most important determinant of maximum oxygen uptake in healthy people. Metabolic studies including  provide a link between impairment and functional capacity6 and can distinguish cardiac versus pulmonary contribution to exercise intolerance.7

provide a link between impairment and functional capacity6 and can distinguish cardiac versus pulmonary contribution to exercise intolerance.7  studies require the use of a nose clip or face mask, which may contribute to perceived exertion in addition to the increased dead space that is created by the inspiratory circuit. In a study comparing the two devices in patients with congestive heart failure, no difference in gas-exchange measurements was observed.8 Perceived exertion, however, was not reported. This is an important finding given that

studies require the use of a nose clip or face mask, which may contribute to perceived exertion in addition to the increased dead space that is created by the inspiratory circuit. In a study comparing the two devices in patients with congestive heart failure, no difference in gas-exchange measurements was observed.8 Perceived exertion, however, was not reported. This is an important finding given that  is a strong predictor of survival (see Chapter 24).

is a strong predictor of survival (see Chapter 24).

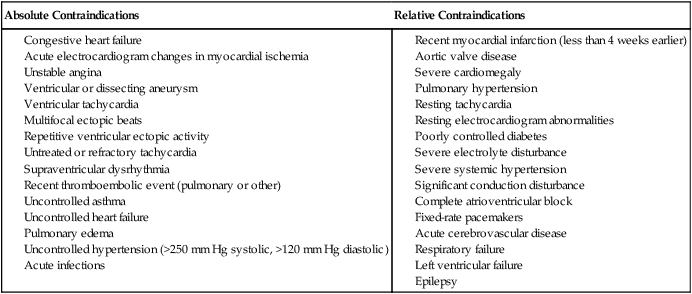

Contraindications to Exercise Testing

Contraindications to exercise testing and, in particular, maximal testing are classified as relative or absolute (Box 19-2). Absolute contraindications prohibit the safe conduction of an exercise test, whereas the presence of relative contraindications requires that the test, protocol, physiological variables monitored, or end point of the test be modified. Both the indications for the test and any contraindications must be clearly established before performing an exercise test.

Adapted from Jones NL, Fletcher J: Clinical exercise testing, ed 4, Philadelphia, 1997, WB Saunders.

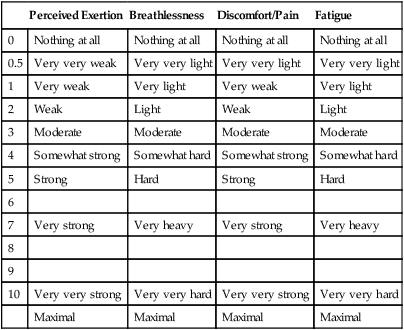

The guidelines used to test and train healthy people with no disease are not directly generalizable to patients with chronic illness who are medically stable. Because of functional impairments in these patients (secondary to cardiopulmonary, cardiovascular, neuromuscular, or musculoskeletal dysfunction), exercise testing and training must be modified. Moreover, patients who are physically challenged experience more subjective symptoms in response to exercise than do healthy people, so monitoring the subjective responses to exercise is essential. The Borg scale of rating perceived exertion can be modified for clinical use to score breathlessness, discomfort, pain, and fatigue (Table 19-3).9,10 If the end points of the scale have been well described and are understood by the patient, the ratings can be used to compare the patient’s subjective exercise responses over repeated tests. The patient’s subjective reports can be correlated with the exercise response and so can provide a basis for exercise prescription as well as avoiding adverse responses.

Table 19-3

Subjective Scales of Exercise Responses

| Perceived Exertion | Breathlessness | Discomfort/Pain | Fatigue | |

| 0 | Nothing at all | Nothing at all | Nothing at all | Nothing at all |

| 0.5 | Very very weak | Very very light | Very very light | Very very light |

| 1 | Very weak | Very light | Very weak | Very light |

| 2 | Weak | Light | Weak | Light |

| 3 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| 4 | Somewhat strong | Somewhat hard | Somewhat strong | Somewhat hard |

| 5 | Strong | Hard | Strong | Hard |

| 6 | ||||

| 7 | Very strong | Very heavy | Very strong | Very heavy |

| 8 | ||||

| 9 | ||||

| 10 | Very very strong | Very very hard | Very very strong | Very very hard |

| Maximal | Maximal | Maximal | Maximal |

Standardization of Exercise Tests and General Procedures

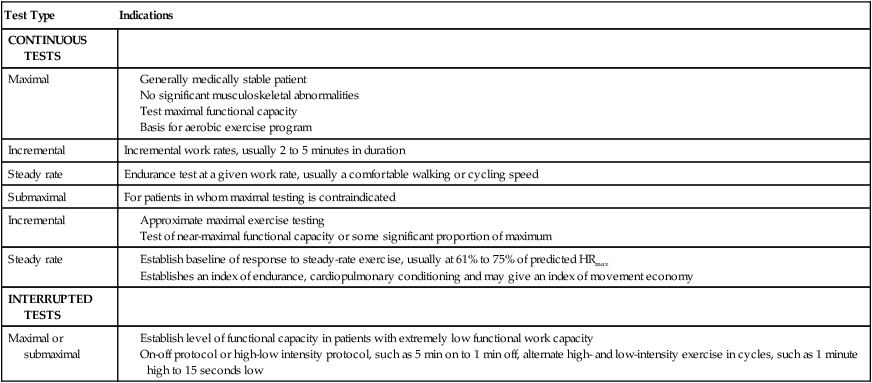

There are numerous variants of standard exercise tests (Table 19-4). They are categorized as continuous tests or interrupted tests. Continuous tests include maximal and submaximal incremental tests and steady-rate tests; interrupted tests include maximal interval and submaximal interval tests. Interrupted tests are designed for patients with low functional work capacity who cannot sustain prolonged periods of aerobic exercise. These patients can perform more work over time when the workload is intermittent. Specifically, the test allows for alternating fixed periods of work and rest or of high and low intensities of exercise. The proportion of work to rest or high to low exercise intensity is set according to the patient’s level of impairment. One patient, for example, may be able to tolerate 3 to 5 minutes of relatively high-intensity work alternated with bouts of 1 to 2 minutes of low-intensity work, whereas another patient may be able to tolerate only 1 minute of low-intensity work alternated with 10 to 20 seconds of rest.

Table 19-4

Exercise Tests Applicable to Patient Populations

| Test Type | Indications |

| CONTINUOUS TESTS | |

| Maximal |

For maximal standardization and the capacity to perform comprehensive monitoring, stationary exercise modalities such as the treadmill, ergometer, or step are recommended. However, there may be indications to perform an exercise test without a modality, such as the 12-minute walk test or some variant like 6 or 3 minutes.11–13 Standardization of such tests, however, is more challenging. Practice has a significant effect on the results of the 12-minute walk test, so this test must be repeated to achieve a valid test. Also, the instructions for this test are less well standardized clinically than are those for the treadmill or ergometer; this jeopardizes stringent test control and thus must be tightly standardized.14

Like other diagnostic and testing procedures, the validity and reliability of the exercise test depend on standardization of the procedures. Test validity and reliability can easily be compromised in the absence of repeated testing and controls.15,16 Early ergometer training responses at rest along with submaximal heart rates and reduction in EMG activity in the arms and legs can reflect familiarization.17 Repeated exercise tests reflect the marked effects of practice. Practice reduces energy output, improves practice-related coordination, and reduces muscle activation.18 However, with good quality control, a test’s validity and reliability can be maximized, even in patients with severe disease such as chronic heart failure.19 The pre-exercise test conditions and the preparation and testing procedures must be standardized (Box 19-3).

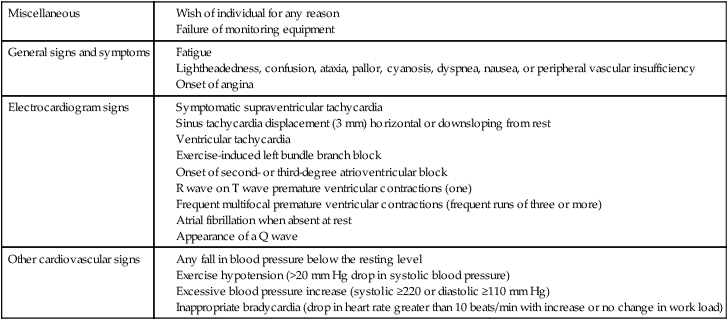

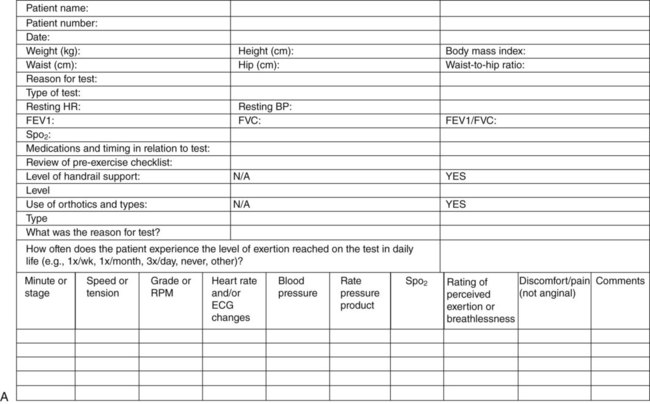

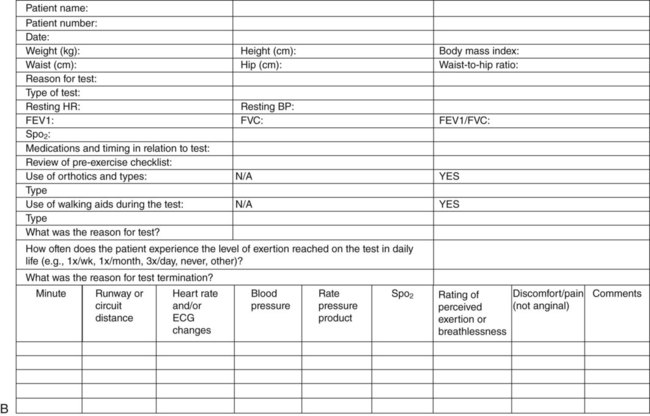

The test is terminated as soon as the sign or symptom criteria for terminating the test are reached or when the criteria for prematurely terminating the test are reached (Table 19-5). Recording the test conditions and procedures in detail is essential. An example of an exercise test data sheet that can be modified to any testing protocol that includes an exercise modality is shown in Figure 19-2, A. Many patients are unable to be exercise-tested using a modality; these patients can walk on a marked circuit, and the results are recorded on an exercise test data sheet similar to the one shown in Figure 19-2, B. Systematic and detailed record keeping will maximize the test’s validity and its interpretation and will ensure that the same procedures are used in follow-up tests, thereby maximizing the comparability of the results of repeated tests. It is imperative that retests be comparable in every respect to the original test in terms of the preparation of the patient and the procedures.

Table 19-5

Criteria for Prematurely Terminating an Exercise Test

Modified from the American College of Sports Medicine. (2010). Guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, ed 8. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; and Jones, N.L., & Fletcher, J. (1997). Clinical exercise testing, ed 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

Nutrition and preexercise meals as they relate to exercise testing and training of individuals with pathology have been given little attention in the literature compared with the attention given to the nutrition of healthy people and athletes. Nutritional preparation in respect to macro- and micronutrients and the timing of meals with respect to activity and exercise could have a major impact on the functional capacity of an individual with oxygen transport impairments and low functional capacity. The performance by healthy people in a session of moderate- to high-intensity exercise for 35 to 40 minutes is improved if they consume a meal moderately high in carbohydrates and low in fat and protein 3 hours before exercise, rather than 6 hours before.20 Missing or delaying meals could alter performance on a test or the outcome of training. Because it has been relatively overlooked in patient populations, nutrition as well as hydration should be a focus of the physical therapy assessment and standardized for the pretest and posttest and training sessions.

Exercise testing is considered resource-intense because of the need for highly qualified individuals to perform tests that are safe, valid, and reliable. In addition, pretest conditions must be met, and the patient has to devote a significant amount of time to taking one or more repeated tests. As a means of streamlining such testing, one study, using two different protocols, compared arterial blood gases and respiratory and metabolic measures in patients who reported shortness of breath.21 One protocol was an incremental exercise test and the other a constant-work protocol. The data generated by both protocols were comparable; however, PaCO2 was somewhat higher during the incremental test, as were exercise stress indexes when compared above the anaerobic threshold. No differences were observed below this threshold.

Exercise Tests and Protocols

Common exercise tests and protocols, along with their psychometric properties, are shown in Appendixes C and D for both maximal and submaximal exercise testing. These serve as an easy reference for the clinician regarding the patients for whom they are suited, their protocols and means of standardizing these tests, and how the results can be interpreted.16 The type of exercise test or tests depends on the patient’s needs and the suitability of various tests to achieve the outcomes of interest. Exercise tests can be used for diagnosis, assessment and evaluation, prognosis, and exercise prescription. The purpose is one major consideration in selecting the specific test and its protocol. The exercise test can be a continuous maximal, a submaximal incremental or steady-rate, or an interrupted maximal or submaximal test. Submaximal tests can be used either evaluatively on their own, or they can be used to predict a maximal exercise response. The protocol for the test and the end points to be used in terminating the test are determined beforehand on the basis of the indications for the test and the objectives. Some commonly used protocols are shown in Figure 18-6, along with a comparison of the energy expenditure required by the various work stages in their protocols.

Evaluative Submaximal Exercise Tests

Step tests, an example of a fixed-rate exercise test in that the load and rate remain constant, emerged as practical field tests several decades ago. With the emergence of a range of field tests since then, step tests are being used less commonly. Nonetheless, when well standardized and selected appropriately for a given person, step tests can provide valuable information about aerobic fitness because they can elicit vigorous exercise intensities. People who are obese and/or physically deconditioned may require supervision when performing a step test.22

The 12-minute walk test and its variants, 6-minute and 3-minute walk tests, were designed to test patients with lung disease.12 These tests have been favored clinically, because they are functional and do not require exercise equipment. However, these tests are often used for patients who have extremely impaired exercise capacity and are unable to tolerate being tested on an exercise modality. A major disadvantage, therefore, is that the patient cannot be as comprehensively monitored. Thus patients who are to undergo a 12-minute walk test or one of its variants must be selected with care.

When the 6-minute walk test is applied to healthy older adults, it has been shown to be reliable; two familiarization tests are needed to minimize arousal and the learning effect.23 In the same trial, the subjects walked, on average, at 80% of  . Based on a comparison with the performance of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to an “encouraged” 6-minute walk test and a standard incremental cycling test, the prognostic value of the walk test was reported to be high.24 Patients achieved a high steady-rate

. Based on a comparison with the performance of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to an “encouraged” 6-minute walk test and a standard incremental cycling test, the prognostic value of the walk test was reported to be high.24 Patients achieved a high steady-rate  in the walk test. No differences were reported in

in the walk test. No differences were reported in  , HR, and arterial blood gases between the two tests at peak. However,

, HR, and arterial blood gases between the two tests at peak. However,  and

and  were lower in the walk test. When performance was “encouraged,” the 6-minute walk test was reported to have good prognostic value.

were lower in the walk test. When performance was “encouraged,” the 6-minute walk test was reported to have good prognostic value.

The 6-minute walk test has been favored as an expedient and inexpensive means of evaluating the functional capacity of older adults with multiple comorbidities. A short distance walked by this cohort is associated with having a low level of education; being non-Caucasian; having a reduced capacity to perform activities of daily living; self-reporting poor health; having a history of heart disease, stroke, or diabetes; and showing abnormal levels of C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and white blood cell count.25

The 6-minute walk test can provide a useful measure of the distance an individual can walk. Because it fails to account for body weight, which is a determinant of exercise capacity, the validity of the 6-minute walk test has been questioned.26 To enhance its usefulness, Carter and colleagues (2003)27 proposed the use of the product of the distance of the 6-minute walk and the body weight, to yield the work involved in the 6-minute walk. This measure provides a more valid measure of exercise performance and, in addition, can be converted to provide an index of calorie expenditure, hence serving as a standardized basis of comparison across exercise modalities.

Recently, the 6-minute walk test has been conducted on a treadmill. Although there are advantages of treadmill tests over field tests, the results of the two types of test may differ, at least in people after cardiac surgery.28

The shuttle test has been another commonly used exercise test for patients with disabilities. When performance on this test is compared with the 6-minute walk distance in patients with COPD, the two tests appear to assess different pathophysiological processes.29 The shuttle test is considered a more accurate predictor of maximal exercise capacity than is the 6-minute walk test.

Predictive Submaximal Exercise Testing

One application of exercise testing in patient populations that has been of interest is to predict  .16 Prediction of

.16 Prediction of  involves a large margin of error in healthy populations, and that margin could be expected to be greater in patients who are likely to be more deconditioned, have comorbidities, and are prone to greater variations in their exercise responses. The Astrand-Ryhming Cycle Ergometer Test continues to be one of the most frequently used submaximal tests for exercise prescription as well as for prediction of

involves a large margin of error in healthy populations, and that margin could be expected to be greater in patients who are likely to be more deconditioned, have comorbidities, and are prone to greater variations in their exercise responses. The Astrand-Ryhming Cycle Ergometer Test continues to be one of the most frequently used submaximal tests for exercise prescription as well as for prediction of  .30 Prediction of

.30 Prediction of  is obtained from a nomogram in which the

is obtained from a nomogram in which the  is estimated from the submaximal HR. To improve its accuracy, an age-correction factor is used to adjust for the age-dependent decrement in HRpeak.31 This ergometer test has the clinical advantage of being applicable to less ambulatory people.

is estimated from the submaximal HR. To improve its accuracy, an age-correction factor is used to adjust for the age-dependent decrement in HRpeak.31 This ergometer test has the clinical advantage of being applicable to less ambulatory people.

Three equations have been compared to predict  in patients with hypertension and fibromyalgia:32 one equation is from the ACSM; one equation is from the Fitness and Arthritis in Seniors Trial (FAST); and the third equation was developed by Foster and colleagues (FOSTER). Predicted

in patients with hypertension and fibromyalgia:32 one equation is from the ACSM; one equation is from the Fitness and Arthritis in Seniors Trial (FAST); and the third equation was developed by Foster and colleagues (FOSTER). Predicted  for all equations was different from the actual measured values. However, the FAST and FOSTER equations predicted values within 1 MET for both patient groups; the ACSM equation predicted values that were different by more than 2 METs.

for all equations was different from the actual measured values. However, the FAST and FOSTER equations predicted values within 1 MET for both patient groups; the ACSM equation predicted values that were different by more than 2 METs.

The distance walked in the 6-minute walk test can provide valid information regarding the functional capacity of elderly patients with chronic heart failure.33 The results are highly correlated with  and can differentiate between classes III and IV of the New York Hospital Association classification of functional capacity.

and can differentiate between classes III and IV of the New York Hospital Association classification of functional capacity.

The heart rate index has recently been described as a means of predicting energy expenditure with the equation METs = 6 × HRindex − 5.34 This equation was based on secondary analysis of 220 data sets (n = 11,257 of multiple ages, pathophysiology and presence/absence of beta blocker therapy) from 60 published exercise studies. These studies reported resting HR (HRrest), a measured-activity HR (HRabsolute), and measured oxygen consumption (mL O2/kg/min) associated with the HRabsolute. HRindex (HRabsolute/HRrest) was calculated. Regression analysis of oxygen consumption (expressed as METs) was performed against HRindex to derive the equation to predict METs. Simple tools are compelling for clinical use and warrant further study.

The oxygen uptake efficiency slope (OUES), which is based on a submaximal test, has been proposed as a valid and reliable index of exercise performance in patients with congestive heart failure.35 This method was tested on older healthy individuals and on patients on the basis of the rationale that maximal testing is not always valid, feasible, or safe. The OUES involves plotting  against the logarithm of total ventilation at submaximal work rates. On repeated tests, the OUES is less variable than endurance or

against the logarithm of total ventilation at submaximal work rates. On repeated tests, the OUES is less variable than endurance or  . Thus the OUES is an objective and reproducible measure of cardiorespiratory reserve based on submaximal effort. The measure reflects ventilatory-circulatory-metabolic coupling and is influenced primarily by pulmonary dead-space ventilation and exercise-induced lactic acidosis.

. Thus the OUES is an objective and reproducible measure of cardiorespiratory reserve based on submaximal effort. The measure reflects ventilatory-circulatory-metabolic coupling and is influenced primarily by pulmonary dead-space ventilation and exercise-induced lactic acidosis.

Maximal Exercise Testing

studies (also called cardiopulmonary exercise tests, or CPETs) have become a primary component of the workup of patients with abnormal exercise tolerance for diagnostic and assessment purposes and for exercise prescription. Metabolic measurement carts are used to conduct these studies. To ensure valid and reliable data, the gases used by the cart must be calibrated and testing procedures tightly standardized before the test as well as during it. A practice session is recommended to reduce learning effects and sympathetic arousal.36 Before the commencement of the test, a couple of minutes of baseline measures are taken, against which the acute exercise responses and the recovery responses can be compared. The metabolic measurement cart can be programmed to display a variety of exercise variables and graphs of interest. The exercise test results are interpreted according to an evaluation of the resting baseline values, the responses of the exercise variables to changes in the exercise test protocol (qualitatively and quantitatively appropriate), the interrelationship of these changes, and whether they achieve some peak value, such as HR or perceived exertion. Beforehand, a decision is made with respect to whether the test is sign- or symptom-limited. Any unusual responses or events during the test are documented. The full impact of the test may not be manifested for several hours or even the next day; thus the patient is followed so that these changes or effects can be evaluated as well. In some patients, lactate measures that require invasive blood work or, minimally, a finger prick, may be indicated.

studies (also called cardiopulmonary exercise tests, or CPETs) have become a primary component of the workup of patients with abnormal exercise tolerance for diagnostic and assessment purposes and for exercise prescription. Metabolic measurement carts are used to conduct these studies. To ensure valid and reliable data, the gases used by the cart must be calibrated and testing procedures tightly standardized before the test as well as during it. A practice session is recommended to reduce learning effects and sympathetic arousal.36 Before the commencement of the test, a couple of minutes of baseline measures are taken, against which the acute exercise responses and the recovery responses can be compared. The metabolic measurement cart can be programmed to display a variety of exercise variables and graphs of interest. The exercise test results are interpreted according to an evaluation of the resting baseline values, the responses of the exercise variables to changes in the exercise test protocol (qualitatively and quantitatively appropriate), the interrelationship of these changes, and whether they achieve some peak value, such as HR or perceived exertion. Beforehand, a decision is made with respect to whether the test is sign- or symptom-limited. Any unusual responses or events during the test are documented. The full impact of the test may not be manifested for several hours or even the next day; thus the patient is followed so that these changes or effects can be evaluated as well. In some patients, lactate measures that require invasive blood work or, minimally, a finger prick, may be indicated.

From the results of CPETs, there are several important variables that can be used clinically. First, determination of the exercise limitation(s) can be made. As described in Chapter 18, the normal limitation to aerobic exercise performance is usually considered to be cardiac output, more specifically, stroke volume. In this case, subjects will exhibit a near maximal heart rate (>90% of age predicted maximum), evidence of a high metabolic demand involving anaerobic energy (respiratory exchange ratio –  – >1.1; or blood lactate levels >8 mmol/L), and near maximal perceptions of effort (rate of perceived exertion >8/10 or >17/20). If these factors are present, a cardiovascular limitation is presumed. In this case, if

– >1.1; or blood lactate levels >8 mmol/L), and near maximal perceptions of effort (rate of perceived exertion >8/10 or >17/20). If these factors are present, a cardiovascular limitation is presumed. In this case, if  values are well below the predicted maximal values, the patient may have some degree of underlying cardiovascular pathology or may simply be deconditioned. Examination of the pre-exercise history, the exercise ECG findings, and the levels of O2 saturation can determine whether the cardiovascular limitation is due to disease or deconditioning. Another common limitation to aerobic exercise observed in clinical exercise testing is due to an inadequate ability to achieve an appropriate level of ventilation. Ventilatory limitations can be detected by the use of pre-exercise spirometry and exercise tidal flow volume loops; or may be detected by comparing the

values are well below the predicted maximal values, the patient may have some degree of underlying cardiovascular pathology or may simply be deconditioned. Examination of the pre-exercise history, the exercise ECG findings, and the levels of O2 saturation can determine whether the cardiovascular limitation is due to disease or deconditioning. Another common limitation to aerobic exercise observed in clinical exercise testing is due to an inadequate ability to achieve an appropriate level of ventilation. Ventilatory limitations can be detected by the use of pre-exercise spirometry and exercise tidal flow volume loops; or may be detected by comparing the  achieved at maximal exercise to the predicted or measured maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV).

achieved at maximal exercise to the predicted or measured maximal voluntary ventilation (MVV).  /MVV >90% is considered to indicate a ventilatory limitation. The interested reader is referred to the ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary exercise testing37 for more information on these topics.

/MVV >90% is considered to indicate a ventilatory limitation. The interested reader is referred to the ATS/ACCP Statement on Cardiopulmonary exercise testing37 for more information on these topics.

Second, CPETs provide a range of exercise performance data, including anaerobic threshold, which is often ignored. Recently, however, the anaerobic threshold has been considered an important marker of cardiovascular insufficiency and exercise performance that has importance in evaluating the performance of individuals with low functional work capacity, such as older adults and patients with left ventricular dysfunction, and in prescribing exercise for them.38,39 In addition, examining the anaerobic threshold may have particular relevance to individuals in these groups, who may be ill-advised to undergo maximal stress tests. From CPET, anaerobic threshold can be determined by the following criteria:

General Testing Considerations

Reproducibility of exercise test results is a particular concern in patient populations whose status may change from day to day. When tested weekly for 4 weeks, patients with stable COPD have been reported to have reproducible submaximal physiological exercise responses and ratings of perceived exertion in response to a constant work rate.40 Exercise performance at a constant work rate is a functional indicator of endurance. On serial exercise testing of patients with chronic heart failure, the mechanical efficiency of walking markedly improves, giving rise to an apparent placebo effect, which has been reported to be independent of motivation and changes in conditioning.41 This factor can invalidate the findings of a single test. Highly trained individuals show a more marked neuroendocrine (sympathoadrenal and hypothalamopituitary adrenal) response in a second bout than in the first bout of exercise performed on the same day.42 Study is needed on the implications of neuroendocrine changes with repeated exercise tests in patient populations.

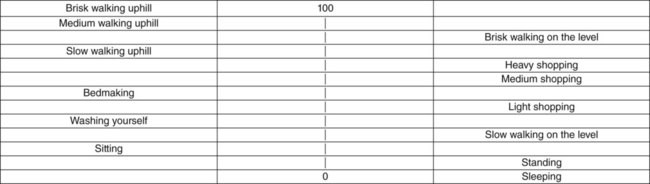

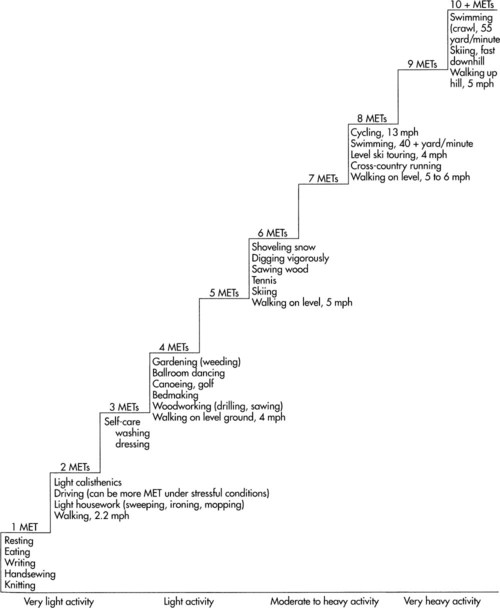

Knowledge of the patient’s functional ability based on verbal report is useful and serves as a guideline for selecting the type of exercise test, its parameters, and the test termination criteria. Although these verbal reports do not replace an exercise test, they can be used as an adjunct. The diagram of oxygen cost is shown in Figure 19-3. This visual analog scale is constructed of a 100-mm line with physical activities hierarchically sequenced based on oxygen cost; the high end of the scale represents strenuous activity (walking briskly uphill) and the low end of the scale represents no activity, or sleep. The patient crosses the line at the point where breathlessness does not allow continuation at the patient’s best (see Figure 19-3). Figure 19-4 shows incremental workloads associated with step increments in metabolic cost—that is, multiples of resting or near resting metabolic rate (resting metabolic rate = 1 MET, or 3.5 mL O2/min/kg of body weight). Metabolic costs of activities range from very light to very heavy activities. One limitation of such charts in indicating the metabolic costs of various activities and exercises is that they can be used only as a general guide in patients with cardiopulmonary compromise, as they do not take into consideration the increased work of breathing and the work of the heart that is observed in patients with cardiopulmonary dysfunction, or the increased energy cost associated with abnormal biomechanics as observed in patients with neuromuscular and musculoskeletal conditions.

Exercise testing and training can be challenging in individuals with physical disabilities, such as those with stroke. Because of this limitation, many patients are denied the potential benefits of diagnostic exercise testing and exercise training. The use of external body supports is one means of providing support during standardized exercise testing on a treadmill. One study examined the metabolic effects of a 15% body-weight support in individuals without impairments.43 End-expiratory gas variables were not affected, except for maximal VT, which was lower with body support; however, time to achieve peak values was increased. The responses of patient populations who would require variable levels of body support have yet to be determined. Another dimension of exercise testing in people with disabilities is the assessment of gait speed, which is associated with physical independence and in activities such as crossing an intersection safely. In addition, gait speed has been proposed as a means of predicting discharge for people with acute stroke. Within the first 5 weeks following stroke, the 5-meter walk test at a comfortable pace (as opposed to the 10-meter walk test, the timed up-and-go test, and other common functional assessment indexes) is the measure of choice for detecting change in walking ability.44 Finally, movement economy can be compromised in people with physical disabilities, given that their movements are biomechanically inefficient (e.g., people with the residua of poliomyelitis).45 Abnormal postural alignment and movement asymmetry need to be considered in patient populations because these impairments can increase the energy cost of a given work rate based on norms.

Exercise testing has a role in preoperative assessment. In combination with other tests and examination, exercise testing in patients as a component of the workup for abdominal aortic aneurysm repair with measurement of P can identify patients at risk for perioperative complications.46 Exercise testing has been used to define a gas-exchange threshold for patients with COPD who are being considered for thoracic surgery.47 A

can identify patients at risk for perioperative complications.46 Exercise testing has been used to define a gas-exchange threshold for patients with COPD who are being considered for thoracic surgery.47 A  of less than 20 mL O2/kg/min has been recommended as the threshold for predicting perioperative complications. Routine preoperative exercise testing has been advocated. Exercise testing has also been recommended to assist in determining the operability of a patient with lung cancer.48,49 Patients may be excluded from lung resection surgery based on conventional medical criteria, yet included based on their

of less than 20 mL O2/kg/min has been recommended as the threshold for predicting perioperative complications. Routine preoperative exercise testing has been advocated. Exercise testing has also been recommended to assist in determining the operability of a patient with lung cancer.48,49 Patients may be excluded from lung resection surgery based on conventional medical criteria, yet included based on their  . These patients have shown survival benefit.

. These patients have shown survival benefit.

Monitoring

Common variables measured during an exercise test include HR, ECG, systolic and diastolic BP, rate pressure product (RPP), RR, SpO2, and subjective responses such as perceived exertion, breathlessness, discomfort, pain, and fatigue (see Chapter 18). Assessment of dyspnea is central to monitoring individuals with breathing and exertional impairments. The Borg scale and the visual analog scale are applicable to individuals with dyspnea, and if assessed in a systematic manner, they can provide valid and reliable measures when used in the patient groups for which they were designed, so they should be used routinely.50 Measures are taken every few minutes after the patient has been exercising at a given intensity for a few minutes when a response to steady-rate exercise is being assessed. This allows for relative stabilization of oxygen kinetics during dynamic exercise. Subjective responses to exercise and daily activities are often the most important to the patient because these typically interfere with their social participation and its composite activities.

Pulse pressure (SBP − DBP) is known to be influenced by aging and arterial wall elasticity.51 Pulse pressure is also influenced by lifestyle interventions, including exercise and diet. Therefore it may serve as an index of changes in arterial wall stiffness with exercise training.

More detailed analysis can be done, depending on the testing or training goals. Noninvasive measures, including transcutaneous oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions, can be readily used to assess gas exchange during testing.52 Invasive monitoring can be done in conjunction with metabolic testing. Such monitoring requires blood sampling through an intraarterial line to examine serial changes in oxygen and carbon dioxide tensions, acid base balance, and arterial saturation, as well as to provide a means for conducting the thermodilution method that yields an index of CO.

The short- and long-term recovery responses, both quantitative and qualitative, in patient populations are important components of the exercise testing profile. The physical therapist must have a thorough understanding of normal physiological recovery responses in order to benchmark abnormal and atypical responses. Sustained elevated BP after cessation of exercise, for example, has been reported to be more sensitive than ECG for detecting myocardial insufficiency. Further, systolic BP after exercise is a strong predictor of hypertension, coronary artery disease, and cardiovascular mortality. An increase in systolic BP and the percent maximum systolic BP 2 minutes after exercise is directly and independently related to risk for stroke.53

Exercise Training Prescription

Exercise Prescription for Health and General Fitness

The components of exercise training for patients for general physical conditioning are the same as those for healthy people: selection of the type of exercise; its intensity, duration, and frequency; and the course of training and its progression. An individualized, rather than standardized, exercise prescription is essential to maximize outcomes in the same way that a physician individualizes a drug prescription.54 The word prescription implies individualization to a person’s needs and goals, including his or her social participation and its composite activities. The selection of the type of exercise used for training and the type used in the exercise test is based on the specific objectives of training.

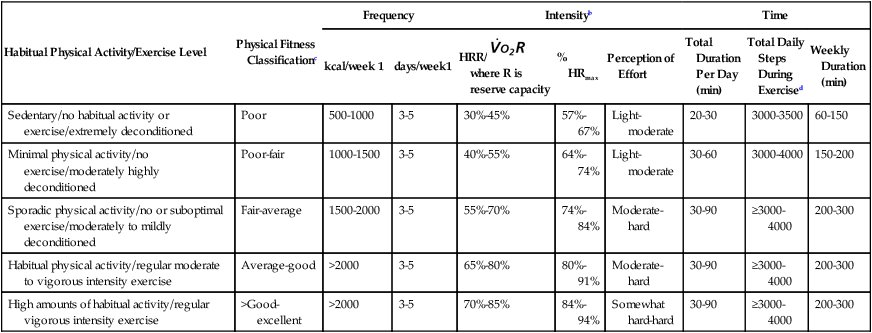

Several expert organizations provide general guidelines for exercise prescription for health and general fitness. Arguably, the foremost of these organizations is the American College of Sports Medicine. The ACSM guidelines are well established and updated frequently; they provide enough guidance to give a comprehensive prescription, but allow enough flexibility to suit the demands of each individual patient. Table 19-6 provides a wide array of examples of how to approach exercise prescription for patients based on their individual level of habitual activity and physical fitness. The FITT approach (frequency, intensity, time, type/mode) to providing exercise prescription ensures that each prescription is detailed enough to be performed by each patient. Although guidelines are just examples, they provide a good starting point from which to design an exercise prescription. These principles are purposefully vague in terms of the exact numbers to use. This range of potential values, particularly for intensity, reflects the fact that improvements in cardiovascular health and fitness can occur with almost any type of exercise prescription within the designated ranges.

Table 19-6

Recommended FITT Framework for the Frequency, Intensity, and Time of Aerobic Exercise for Apparently Healthy Adultsa

| Habitual Physical Activity/Exercise Level | Physical Fitness Classificationc | Frequency | Intensityb | Time | |||||

| kcal/week 1 | days/week1 | HRR/ where R is reserve capacity where R is reserve capacity |

% HRmax | Perception of Effort | Total Duration Per Day (min) | Total Daily Steps During Exercised | Weekly Duration (min) | ||

| Sedentary/no habitual activity or exercise/extremely deconditioned | Poor | 500-1000 | 3-5 | 30%-45% | 57%-67% | Light-moderate | 20-30 | 3000-3500 | 60-150 |

| Minimal physical activity/no exercise/moderately highly deconditioned | Poor-fair | 1000-1500 | 3-5 | 40%-55% | 64%-74% | Light-moderate | 30-60 | 3000-4000 | 150-200 |

| Sporadic physical activity/no or suboptimal exercise/moderately to mildly deconditioned | Fair-average | 1500-2000 | 3-5 | 55%-70% | 74%-84% | Moderate-hard | 30-90 | ≥3000-4000 | 200-300 |

| Habitual physical activity/regular moderate to vigorous intensity exercise | Average-good | >2000 | 3-5 | 65%-80% | 80%-91% | Moderate-hard | 30-90 | ≥3000-4000 | 200-300 |

| High amounts of habitual activity/regular vigorous intensity exercise | >Good-excellent | >2000 | 3-5 | 70%-85% | 84%-94% | Somewhat hard-hard | 30-90 | ≥3000-4000 | 200-300 |

aThe various methods to quantify exercise intensity in this table may not necessarily be equivalent to each other.

bFitness classification based on normative fitness data categorized by

cPerception of effort using the ratings of perceived exertion (RPE), OMNI, talk test, or feeling scale.

Intensity

The intensity of exercise is arguably the most important aspect of exercise prescription and is usually set at some proportion of the HR response or some other response, to a maximum or near-maximum work rate that was safely tolerated during an exercise test. The training intensity for a relatively fit individual who is able to tolerate several incremental work stages on a graded exercise test may be optimal between 65% and 85% of the heart rate reserve (HRR) achieved in the test. The HRR is calculated by taking the percentage intensity within the physiological range from rest to maximum. Thus HRR is equal to (HRmax – HRrest) × intensity fraction + resting heart rate. HRmax can be estimated based on a predicted HRmax such as 220 − age. This predicted maximum is associated with significant error ± 10 beats (i.e., deviation from the actual HRmax achieved in a maximal test), thus the HR at which training is eventually conducted is refined on the basis of other indexes, such as the talk test and general responses. The ratio of HRmax (actual or predicted) and resting HR (the heart rate ratio method) provides a good estimate of  in healthy men and may have some application in some patient populations.55

in healthy men and may have some application in some patient populations.55

A patient who is unable to tolerate a couple of increases in work stage is more likely to benefit from an exercise intensity range of 30% to 50% of HRR. In some patients, HR is an invalid indicator of exercise intensity because of the pathology or medications.45,56 Thus other responses, such as BP, arterial saturation, or subjective parameters such as rating of perceived exertion or breathlessness, can be used. Use of subjective symptoms to supplement the training parameters is useful in patients whose objective exercise responses may be spurious and less valid (e.g., patients on medications that alter autonomic activity).

Time and Frequency

The duration (time) and frequency of the exercise program are established based on the patient’s functional capacity, physiological reserve capacity, and exercise responses (see Table 19-6 for general guidelines). Patients with low functional capacities but with adequate physiological reserve capacity respond quickly to a training stimulus (short training course), so they should be progressed accordingly. However, patients with low functional capacities and with limited physiological reserve capacity adapt more slowly (long training course). The shorter the training course, the sooner a retest is indicated to progress and reset the training parameters. To ensure that the patient continues to be trained safely and optimally, the training parameters should be progressed based on an exercise retest.

Type

The type or mode of exercise should be specific to the individual goals of the client, but should involve a large amount of muscle mass and should be relatively functional. For these reasons, walking, cycling, running, and swimming are often prescribed. Hemodynamic exercise responses depend on the type of exercise and the degree of static exercise and postural stabilization involved and on the muscle mass recruited. Depending on the patient’s status and diagnoses, hemodynamic responses have to be considered. The HR response to ergometer rowing using the arms and legs, for example, is lower than running for the same relative workload.57 Correspondingly, venous return,  and O2 pulse are also greater in rowing.

and O2 pulse are also greater in rowing.

Water exercise, including chair exercise in the water and running, are undergoing a revival in physical therapy for the management of chronic conditions. Water provides buoyancy, prevents injury, reduces spinal loading and lower extremity loading, minimizes muscle soreness, and optimizes temperature control to facilitate exercise performance. Long-term effects of water exercise such as deep-water running include increased blood volume, increased stroke volume, and increased cardiac output.58 Water exercise for strength or cardiovascular endurance has benefits for training and for recovery from injury. Aquatic exercise programs have the advantage of being offered to groups as a way of improving fitness in healthy individuals and in people with pathologies such as stroke.59

Cross-training principles analogous to those used in athletes apply to patients.60,61 Based on the assessment of oxygen transport deficits and threats and goals for the individual (e.g., function, health, fitness, prevention, or a combination), a decision is made regarding the prescription of a single mode or a dissimilar mode of training. Because of the specificity of exercise principles, the generalization of a single-mode exercise cannot be assumed; thus, other types of exercise, including task-specific exercise, may have to be included. Also, consideration should be given to the cross-transfer effects of exercising one side of the body. Cross-transfer between ipsilateral and contralateral limbs should be considered when focusing attention on one side of the body or to limit detraining during periods of unilateral immobilization.

Developing exercise programs for the masses of sedentary people in the community constitutes one of the greatest challenges to the physical therapist. Motivating people to be physically active in their daily lives and undertake a formal program of exercise is a skill in itself (see physical activity pyramid in Chapter 1). Intermittent bouts of exercise accumulated throughout the day are showing acceptance by the public and are producing favorable results. The 10,000-steps-per-day program encourages individuals to wear a pedometer and become conscious of how closely they approximate this guideline, which has been associated with an “active” lifestyle.62 With this objective information, people may be more inclined to increase the number of their daily steps so as to improve their health by elevating the range of their daily steps from the inactive to the active lifestyle. Another creative public health initiative is a stair-climbing program in the community. Such a program has been directed toward sedentary young women.63 The 7-week program of stair climbing involves progressing from one flight to several flights daily using a public-access stairway of 199 steps. This short-term exercise program resulted in aerobic conditioning as evidence by reduced  , HR, and lactate during stair climbing and by improved cholesterol levels. Such innovative approaches have enormous potential for improving public health.

, HR, and lactate during stair climbing and by improved cholesterol levels. Such innovative approaches have enormous potential for improving public health.

Exercise Training to Improve Tasks or Performance

A significant difference between exercise prescription for health and training program design is that training programs often require long-term periodization in order to address multiple needs. Usually, this type of training design involves structuring periods of training that progress from more general to more task- or performance-specific. In the example of the patient wanting to increase anaerobic threshold, the physical therapist would usually begin the program with some lower intensity aerobic exercise for 3 to 8 weeks designed to increase overall endurance and tolerance to walking. After this initial period of “aerobic base” training, the physical therapist would progress the program by prescribing training to increase anaerobic threshold. This type of training program design is complex, and a full description is beyond the scope of this chapter; however, physical therapists working with patients requiring improvements in specific tasks/performance should be competent in comprehensive program design.64

Emerging Alternate Types of Exercise Prescription

For many patients, continuous aerobic training as described above is either ineffective, inefficient, or intolerable (see Chapters 18, 34, and 35). There are a few promising methods of altering aerobic exercise prescription techniques that help to minimize these limitations. One example is the use of single-limb training (as opposed to double-limb). As mentioned in Chapter 18, patients who exhibit inability to exercise at high enough intensities to elicit significant physiological benefit due to impairments of central cardiovascular or respiratory responses can increase their muscle specific peripheral load by restraining exercise in one limb. Dolmage and Goldstein (2008)65 found that single-limb cycling in patients with COPD allowed patients to rapidly progress single-limb workload, resulting in a significantly greater increase in  than the group who trained using two-legged cycling (22% versus 1%, respectively). This increase in

than the group who trained using two-legged cycling (22% versus 1%, respectively). This increase in  was achieved during a double-legged cycling GXT. What is most striking about this study is the fact that the overall training time between the two groups was the same. The double-legged training group cycled for 30 minutes continuously, whereas the single-limb group exercised one leg for 15 minutes, then switched legs for the remaining 15 minutes. There are two main conclusions that can be made in regard to the physiological adaptations achieved with single-limb training. First, it appears that progression of overall intensity beyond what is capable through double-legged training in this population is much more important than overall training time. Second, because

was achieved during a double-legged cycling GXT. What is most striking about this study is the fact that the overall training time between the two groups was the same. The double-legged training group cycled for 30 minutes continuously, whereas the single-limb group exercised one leg for 15 minutes, then switched legs for the remaining 15 minutes. There are two main conclusions that can be made in regard to the physiological adaptations achieved with single-limb training. First, it appears that progression of overall intensity beyond what is capable through double-legged training in this population is much more important than overall training time. Second, because  increased in the single-limb group on a double-limbed test, the mechanisms for increases in

increased in the single-limb group on a double-limbed test, the mechanisms for increases in  are likely due to peripheral adaptations. It has been proposed that adaptations at the level of muscle mitochondria are most apparent with maximizing the amount of tissue oxygenation to minimize the circulating PO2.66,65

are likely due to peripheral adaptations. It has been proposed that adaptations at the level of muscle mitochondria are most apparent with maximizing the amount of tissue oxygenation to minimize the circulating PO2.66,65

Another example of a promising method of exercise training is the use of high-intensity interval training. Although typically thought of as an “athletic” type of training, high-intensity interval training has been used successfully in patients with cardiovascular and respiratory disease. In patients with COPD, for example, ventilatory limitations prevent continuous exercise performance at high intensities.67 As such, interval exercise models can be used to attempt to increase overall workload during exercise and to enhance muscular adaptation.68,69 Interval exercise involves alternating periods of higher intensity work bouts (termed work phase) with those of lower intensity (termed recovery phase). The results of training studies reported to date in COPD indicate that high-intensity interval training (at a work phase of 90% to 100% of peak aerobic power) increases muscle performance and exercise tolerance to a similar degree as continuous training, with less ventilatory limitation and dyspnea.68,69 In addition, the adaptations achieved in skeletal muscle are comparable to those achieved by continuous training. Meyer and colleagues (1996)70 used high-intensity interval training at a work phase of approximately 120% of peak aerobic power compared with a continuous exercise protocol at 75% of peak power in patients with chronic heart failure. The interval exercise protocol resulted in greater exercise times, with reduced levels of ventilatory and cardiac stress and reduced symptoms of fatigue and dyspnea. After only 3 weeks of training at this high intensity, these patients achieved remarkable increases in maximal aerobic power and leg muscle performance, with reduced symptoms and stress during training.70

Recovery and Overtraining

The prescription of the parameters for optimal physiological recovery has not been described in detail. However, the practice of progressive, decremental exercise intensity in the form of a warm-up is supported. Such activity facilitates venous return and the return of HR and other exercise parameters to baseline values.71 In addition, light activity after exercise promotes the degradation of circulating catecholamines. Priming exercise in athletes improves performance,72 and this result can be expected in nonathletes as well. However, the parameters (i.e., exercise type, intensity, and duration) of an optimal warm-up have yet to be defined, and they may depend on the individual, general health and fitness, weight, age, and morbidity.

New advances in athletic training may have application to clinical populations, including titrating, or periodizing, training day by day, week by week, or month by month. Periodization has two primary goals: to structure a training program to achieve optimal, multiple physiological adaptations and to prevent overtraining. An overtraining phenomenon has been described in healthy people. Athletes whose performance has dropped off may improve performance outcomes with several weeks of rest.73 Prevention of overtraining is achieved through a detailed analysis of the responses to and recovery from the previous exercise session. This method is based on modeling the effects of training, detraining, and overtraining.74,75 This method does not assume that the interval between exercise sessions is the same across individuals or the same for a given individual from one day to the next. The proponents of the model believe that training is optimized by the avoidance of under- or overtraining and that training effects are better if they are accumulated over time, rather than according to the conventional methods that subscribe to a rigid exercise intensity, duration, and frequency over some interval (e.g., 6 to 8 weeks).

The role of overtraining in people with underlying pathology, whether induced by the pathology or resulting from an excessive therapeutic exercise prescription, is not well understood. The extent to which some severely compromised patients are, in fact, overtrained as a mere consequence of their activities of daily living is not known. It is possible that the syndrome of inability to maintain work performance, persistent fatigue, frequent illness (in particular upper respiratory tract infections), disturbed sleep, and altered mood states may reflect overwork in patients that is analogous to overtraining in athletes.76,77 With respect to immunity, reduced neutrophil function may be implicated in both situations. In athletes, this overtraining syndrome due to excessive physical exertion and inadequate recovery has been related to autonomic dysfunction and increased cytokine production. Because regular intense exercise can suppress mucosal immunity and because saliva is the most commonly used secretion for assessing mucosal immunity, monitoring the saliva of athletes during critical training periods provides an index of risk status. The usefulness of mucosal assessment in clinical populations warrants investigation. Relaxation has been shown to offset the exercise-induced suppression of secretory immunoglobulin associated with upper respiratory tract infection in healthy people.78 The role of relaxation and its immune protection warrants exploitation in clinical populations. Immunity may be optimized with an appropriate balance of exercise, rest, and recovery. Achieving an optimal balance of exercise and rest or recovery warrants study in patient populations as a means of maximizing a patient’s social participation.

Exercise Prescription

General Procedures

Before an exercise session, the patient needs to review a checklist to ensure that exercise is not contraindicated on that day. This is particularly important for patients whose conditions change rapidly or whose disease course tends to fluctuate, as in multiple sclerosis, cystic fibrosis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and congestive heart failure. Box 19-4 provides a checklist to be used in preparation for exercise testing and training sessions. Such a checklist, however, must be tailored to each patient. Aids and devices for older patients must provide assistance that is optimal and safe and promotes the most independence. Inappropriate aids are associated with poor patient outcomes in this population, and their use requires more surveillance by carers.79

Active exercise is always selected to elicit optimal oxygen transport stress for improving aerobic and muscle power. Passive exercise, however, may have a limited role in some patients. Compared with active exercise, little is known about the physiological responses to passive exercise. When low-intensity active and passive cycling are compared in healthy people, inotropic changes are elicited primarily with active exercise, thus are dependent on mechanoreflexes stimulated by the metabolic products of skeletal muscle.80 Cardiac output is increased by an increase in HR during active cycling and by an increase in stroke volume during passive cycling. It is interesting to note that blood lactate increases in both active and passive cycling but is higher during active cycling. These findings are of some physiological interest and may have potential therapeutic application; however, active exercise is the therapeutic priority, no matter how minimal the absolute intensity, duration, and frequency may be initially. The degree to which passive exercise could be exploited in individuals unable to cooperate with an exercise program, or whether passive exercise could augment active exercise, warrants further study.

Monitoring

The HR, BP, RR, and other measure are taken according to standardized procedures. Electronic equipment and mechanical devices must be calibrated. A break point in the double product (HR × systolic BP) and work-rate relationship can provide a good estimate of the anaerobic threshold in patients with exercise intolerance as well as in healthy persons.81

The World Health Organization recommends repeated BP measurements be performed in the sitting or supine position followed by standing82 and that the cuff be positioned at the level of the right atrium, irrespective of body position. One concern about this recommendation is that systolic and diastolic BP is lower in a sitting than in a supine position, so the two readings are not equivalent.83 Blood pressure may be under- or overestimated if the level of the cuff is not at the level of the right atrium, regardless of body position. Further, this effect may be amplified in patients with autonomic dysfunction such as that found in patients with diabetes.

Most evidence related to exercise and health has focused on cardiovascular conditioning. The relationship between other dimensions of health is being increasingly studied—for example, immunological status84 and mental health.85 With respect to mental health, little is known about the parameters of exercise that are optimally antidepressive, other than benefits may be associated with regular physical activity, preferably engaged in with other people. Although there is an association between depressive symptoms and reduced activity in community-living older adults, research is needed to establish the role of exercise training in preventing or attenuating these symptoms.85

plateau

plateau reaching a nadir and increasing incrementally after this point

reaching a nadir and increasing incrementally after this point is considered by many to be the gold standard for determination of fitness. Although this point is debatable,

is considered by many to be the gold standard for determination of fitness. Although this point is debatable,  reference values that are specific to age and gender are widely used to determine an individual’s level of fitness. In terms of prescribing exercise training, values at peak exercise such as HRmax and work rate maximum can be used to help set appropriate levels of intensity.

reference values that are specific to age and gender are widely used to determine an individual’s level of fitness. In terms of prescribing exercise training, values at peak exercise such as HRmax and work rate maximum can be used to help set appropriate levels of intensity. ), a maximal GXT may be conducted. A maximal GXT without respiratory monitoring holds the same level of risk associated with CPETs, but it will still provide valid information on maximal work rate attained and also on a subject and modality specific maximal heart rate. In this case, an achieved maximal heart rate or maximal work rate can be used to prescribe exercise training intensity more accurately than using an age-predicted maximal heart rate or a predicted maximal work rate based on submaximal testing. In addition, if all of the monitoring requirements other than

), a maximal GXT may be conducted. A maximal GXT without respiratory monitoring holds the same level of risk associated with CPETs, but it will still provide valid information on maximal work rate attained and also on a subject and modality specific maximal heart rate. In this case, an achieved maximal heart rate or maximal work rate can be used to prescribe exercise training intensity more accurately than using an age-predicted maximal heart rate or a predicted maximal work rate based on submaximal testing. In addition, if all of the monitoring requirements other than  are maintained (ECG, Sp

are maintained (ECG, Sp

, oxygen uptake reserve; HRR, heart rate reserve; %HRmax, percentage of age-predicted maximal heart rate.

, oxygen uptake reserve; HRR, heart rate reserve; %HRmax, percentage of age-predicted maximal heart rate. measurement to allow the estimation of this individual’s anaerobic threshold (as a marker of maximal sustainable pace). The exercise training program would be designed to have the patient increase her anaerobic threshold (using an intensity of exercise at or around anaerobic threshold).

measurement to allow the estimation of this individual’s anaerobic threshold (as a marker of maximal sustainable pace). The exercise training program would be designed to have the patient increase her anaerobic threshold (using an intensity of exercise at or around anaerobic threshold).