1 Mitral stenosis

Instruction

This patient developed shortness of breath and orthopnoea during pregnancy, please examine.

This 55-year-old patient has atrial fibrillation, please do the relevant clinical examination.

Salient features

History

Examination

• Pulse is regular or irregularly irregular (from atrial fibrillation).

• Jugular venous pressure (JVP) may be raised.

• Tapping apex beat in the 5th intercostal space just medial to midclavicular line.

• Left parasternal heave (indicating right ventricular enlargement).

• Opening snap (OS; often difficult to hear; a high-pitched sound that can vary from 0.04 to 0.10 s after the second sound (S) and is heard best at the apex with the patient in the lateral decubitus position).

• Rumbling, low-pitched, mid-diastolic murmur, best heard in the left lateral position on expiration. In sinus rhythm there may be presystolic accentuation of the murmur. If you are not sure about the murmur, tell the examiner that you want the patient to perform sit-ups or hopping on one foot to increase the heart rate. This will increase the flow across the mitral valve and the murmur is better heard.

Notes

1 Remember the signs of pulmonary hypertension include loud P2, right ventricular lift, elevated neck veins, ascites and oedema. This is an ominous sign of the disease progression because pulmonary hypertension increases the risk associated with surgery (Br Heart J 1975;37:74–8).

2 In patients with valvular lesions, a candidate would be expected to comment on rhythm, the presence of heart failure and signs of pulmonary hypertension.

3 In atrial septal defect, large flow murmurs across the tricuspid valve can cause mid-diastolic murmurs. The presence of wide, fixed splitting of second sound, absence of loud first heart sound, and an opening snap and incomplete right bundle branch block should indicate the correct diagnosis. However, about 4% of the patients with atrial septal defect have mitral stenosis, a combination called Lutembacher syndrome.

Questions

What is the natural history of mitral stenosis?

• From the occurrence of rheumatic fever to the onset of symptoms, there is a long latent period of 20 to 40 years in Europe and North America.

• Moreover, there is a further period of about 10 years before symptoms become disabling.

• The 10-year survival of untreated patients is 50% to 60%, depending on symptoms at presentation:

How does one determine clinically the severity of the stenosis?

• The narrower the distance between the second sound and the opening snap, the greater the severity. The converse is not true. (Note: This time interval between the second sound and opening snap is said to be inversely related to the left atrial pressure.)

• The longer the duration of the diastolic murmur, the greater the severity. Note that in tight mitral stenosis the murmur may be less prominent or inaudible and the findings may be primarily those of pulmonary hypertension.

Advanced-level questions

What are the investigations you would do?

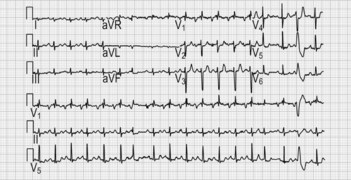

• ECG shows broad bifid P wave (P mitrale); atrial fibrillation in advanced disease, left atrial enlargement, right ventricular hypertrophy (Fig. 1.1).

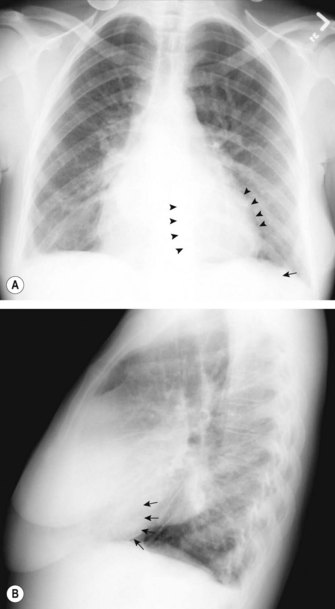

• Chest radiography (Fig. 1.2) shows:

• Echocardiography: two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography is the diagnostic tool of choice for assessing the severity of mitral stenosis and for judging the applicability of balloon mitral valvotomy (N Engl J Med 1997;337:32–41):

• A transoesophageal echocardiography is not required unless a question about diagnosis remains after transthoracic echocardiography. It is also useful to exclude thrombus in the left atrial appendage before balloon valvotomy or cardioversion.

• Coronary angiography may be required in selected patients who need intervention.

• Exercise haemodynamics should be performed when the symptoms are out of proportion to the calculated mitral valve gradient area.

What is the normal cross-sectional area of the mitral valve?

It ranges from 4 to 6 cm2 and turbulence of the flow occurs when this area is <2 cm2.

How would you manage the patient?

• Asymptomatic patient in sinus rhythm: prophylaxis against infective endocarditis only.

• Mild symptoms: diuretics to reduce left atrial pressure and, therefore, symptoms.

• Anticoagulation should also be considered in patients with left atrial dimensions ≥55 mm.

• Moderate to severe symptoms or pulmonary hypertension is beginning to develop: mechanical relief of valve stenosis, including balloon valvotomy (N Engl J Med 1994;331:961–7, Br Heart J 1988;60:299–308) (percutaneous mitral balloon valvuloplasty is usually the procedure of choice when there is a non-calcified pliable valve) or surgery.

What are the indications for surgery?

• Patients with severe symptoms of pulmonary congestion and significant mitral stenosis (mitral valve area ≤1.5 cm2).

• Patients with pulmonary hypertension (pulmonary artery systolic pressure >50 mmHg at rest or 60 mmHg with exercise) or haemoptysis even if minimally symptomatic.

• Recurrent thromboembolic events despite therapeutic anticoagulation.

Which surgical procedures are used to treat mitral stenosis?

• Open commissurotomy requires cardiopulmonary bypass and allows surgical repair of the valve under direct vision resulting in more effective and safer valvotomy than the closed procedure.

• Valve replacement entails risks including thromboembolism, endocarditis and primary valve failure.