Chapter 6 Mitral Stenosis

Introduction

Mitral stenosis is quite uncommon in Western countries, yet it still is a frequent problem worldwide, particularly in developing countries. The low incidence in the United States, in particular, is largely because rheumatic fever resulting in rheumatic heart disease has been largely eradicated; nevertheless, occasional outbreaks do occur. The occurrence of rheumatic fever in Utah in the mid-1980s and early 1990s is notable.1,2 That particular outbreak had two unusual aspects. First, as opposed to previous history of outbreaks typically appearing in lower socioeconomic groups, this outbreak seemed to affect the middle class. Second, there was a distressingly low incidence of a symptomatic streptococcal infection in the group developing rheumatic fever.

Rheumatic heart disease preferentially affects the mitral valve, with the order of involvement being (1) mitral, (2) aortic, (3) tricuspid, and (4) pulmonic. The mitral valve is involved in virtually all cases, whereas the aortic valve is affected in 20% to 25% of cases. Pulmonary valve involvement in rheumatic heart disease is exceedingly rare. Even though the tricuspid valve frequently is involved, tricuspid valvular disease often is clinically silent.3 From a functional standpoint, however, approximately 25% of patients with rheumatic heart disease have pure mitral stenosis and 40% have a combination of mitral stenosis and mitral regurgitation.4 Two thirds of all patients with rheumatic mitral stenosis are female5; however, in my experience, it is almost 90%. In the United States and other Western countries, mitral stenosis develops over a period of decades, with a mean age of onset of 45 years. However, for reasons that are not entirely understood, individuals in developing countries such as India, in Africa, and in Alaskan Inuits, the time from rheumatic fever to onset of clinically significant mitral stenosis can be as little as 10 years. The factors for this rapid onset, however, appear to be more socioeconomic than necessarily related to specific medical care.6,7

Cardiac Imaging and Real-Time Three-Dimensional Echocardiography

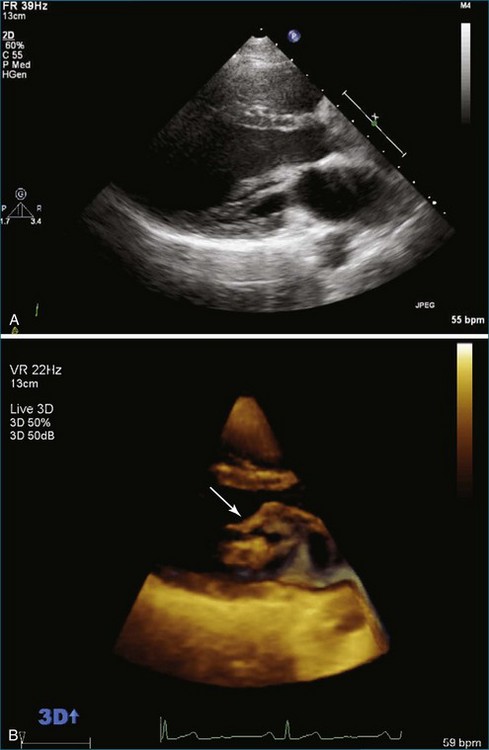

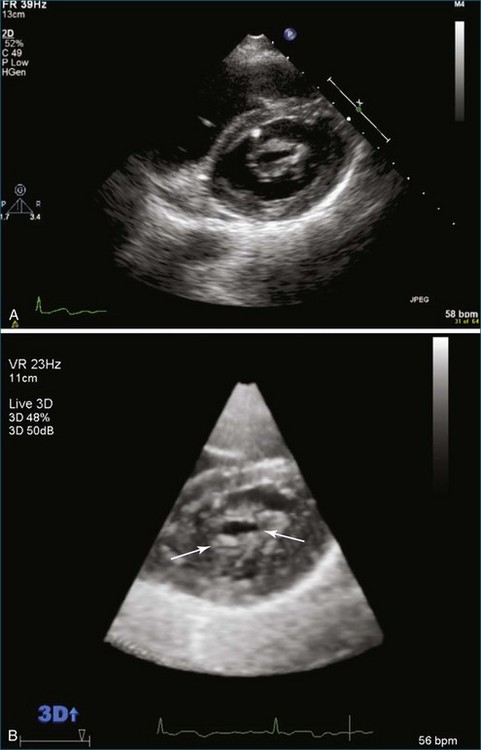

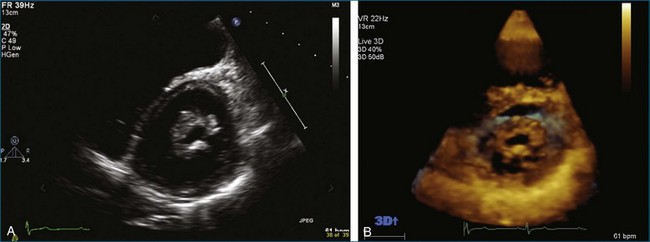

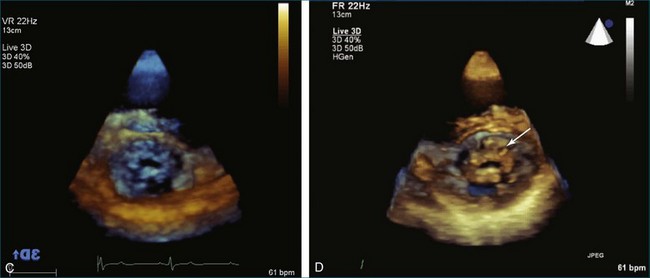

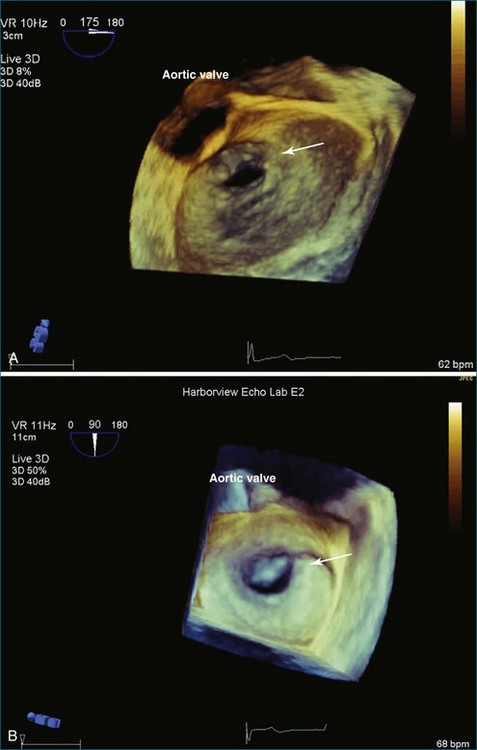

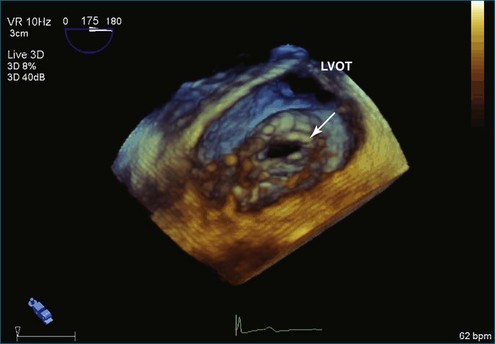

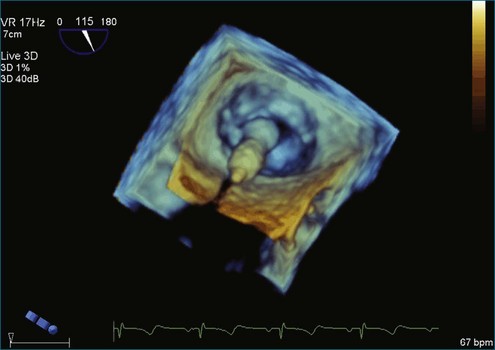

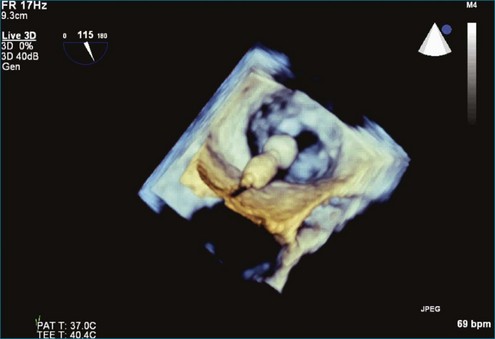

From the standpoint of cardiac imaging, echocardiography is clearly the mainstay for evaluation of mitral stenosis. The extent of mitral valvular deformity traditionally has been evaluated by two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography and graded based on a score of 0 to 4 for each of four factors: (1) valvular thickening, (2) valvular mobility, (3) degree of leaflet calcification, and (4) extent of subvalvular thickening and calcification.8 The Wilkins scoring system does have several drawbacks, however. In particular, some patients with a high Wilkins score still respond well to percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty (PMV). Three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography provides incremental information regarding the status of rheumatic involvement of the mitral valve, particularly regarding the fusion of the commissures. Determination of the status of commissural fusion, particularly the symmetry and length of commissural fusion, is critical information to predict the success of treatment of mitral stenosis with PMV.9 That is, mitral valvuloplasty is most effective when extensive symmetric commissural fusion is present and when such fusion is alleviated at the time of the procedure. 3D echocardiography (3DE) has a particular strength for visualizing the mitral commissures and commissural fusion because of the added dimension of elevation (Figures 6-1 to 6-5; Videos 6-1 to 6-9). The elevation dimension allows clearer assessment of the degree and length of commissural fusion as well as the presence of structures that could inhibit the process, such as rheumatic nodules and subvalvular (typically chordal) thickening. Although in mitral stenosis symmetric commissural fusion is the optimal morphology for PMV success, evidence indicates that if the commissural fusion is accompanied by significant calcification, results are not as satisfactory, which is a predictable finding.10–12

Mitral Valve Area Determination

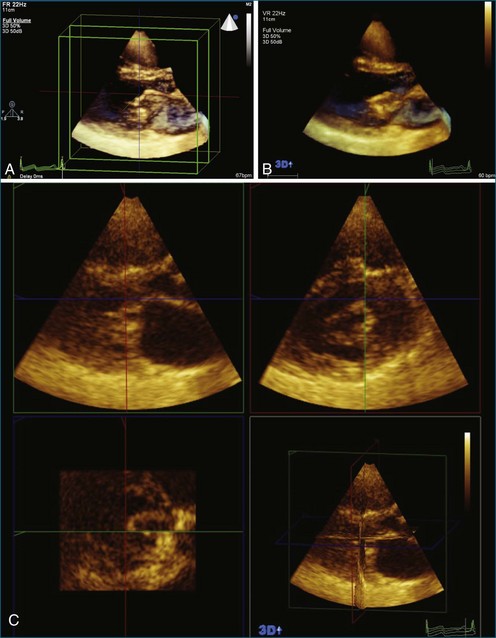

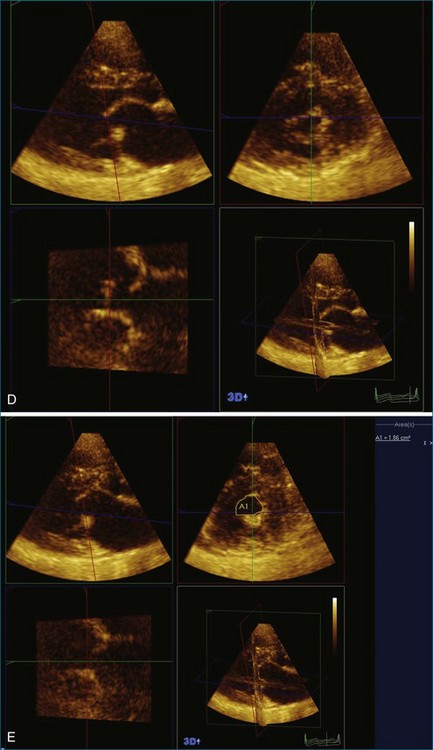

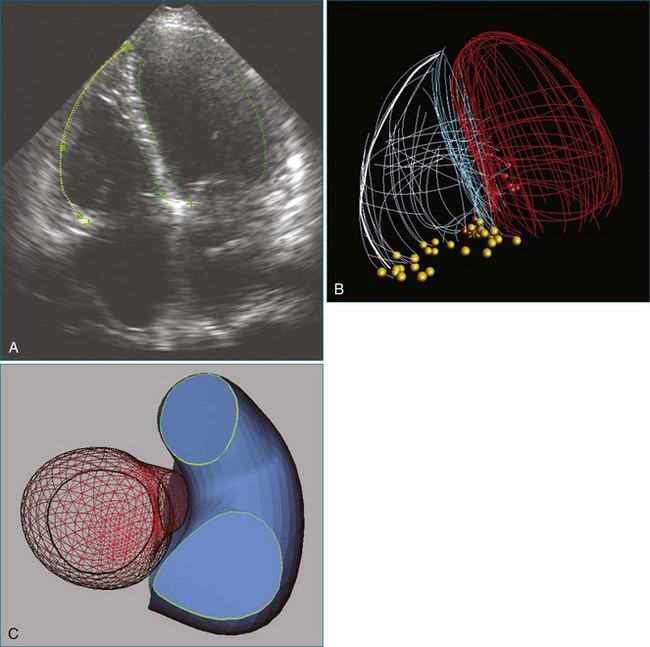

The severity of mitral stenosis can be determined by several echocardiographic measures: peak and mean pressure gradient by Doppler and mitral valve area by (1) Doppler pressure half-time, (2) Doppler-based continuity equation, and (3) direct planimetry of the mitral valve area by 2DE or 3DE. Direct planimetry of the mitral valve orifice by real-time 3DE (RT3DE) has now emerged as the gold standard, thanks to several investigations and publications.13–20 RT3DE quantification of the mitral valve orifice begins with a full-volume RT3D transthoracic echocardiography (RT3DTTE) acquisition obtained in the parasternal long-axis orientation. From this full-volume dataset, the mitral valve can be cropped to obtain an en face view of the mitral orifice. A precise en face image of the stenotic mitral valve is crucial for accurate measurement of the mitral valve area. In addition to being lined up with the tips of the mitral valve leaflets using the orthogonal plane, the en face view can be panned above and below the valve and viewed from the atrial and ventricular sides. The cropping function markedly enhances the confidence in the accuracy of valve area quantification because multiple plane cropping ensures that the orifice area is traced in a plane that is (1) at the tips of the mitral valve and (2) perpendicular to the inflow through the valve. The progression shown in Figure 6-3 demonstrates the sequential plan for procurement of an accurate mitral valve area using planimetry of an RT3DE dataset. Note that such a dataset could be obtained using either RT3DTTE or RT3D transesophageal echocardiography (RT3DTEE).

Treatment: Percutaneous Mitral Valvuloplasty

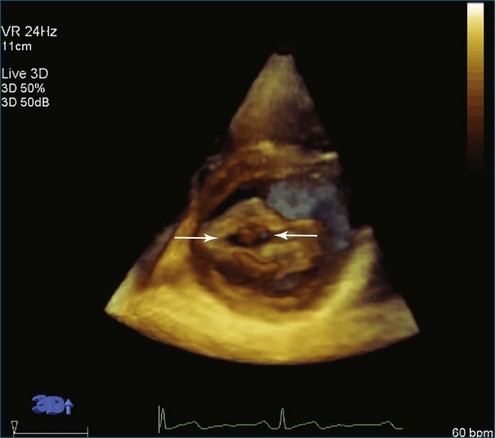

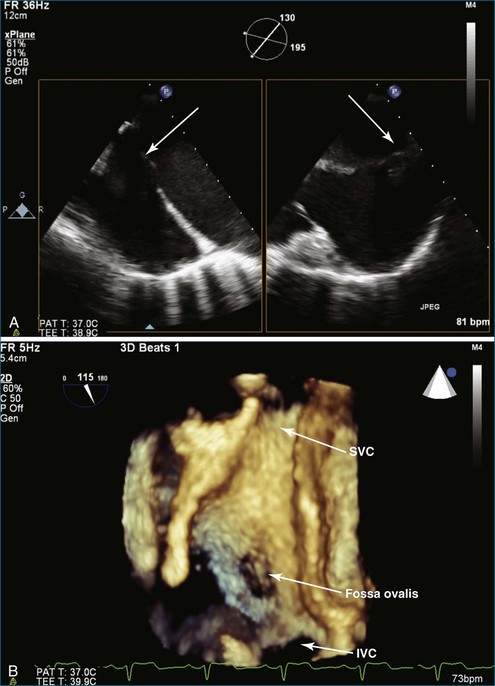

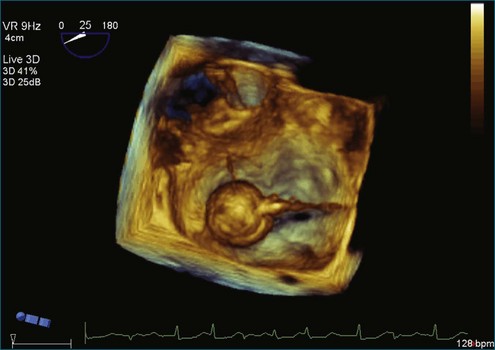

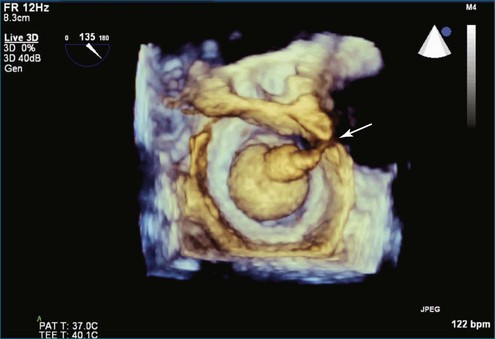

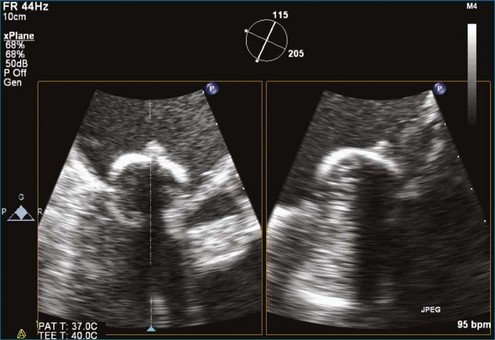

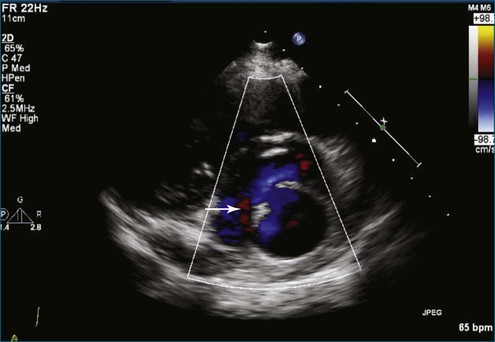

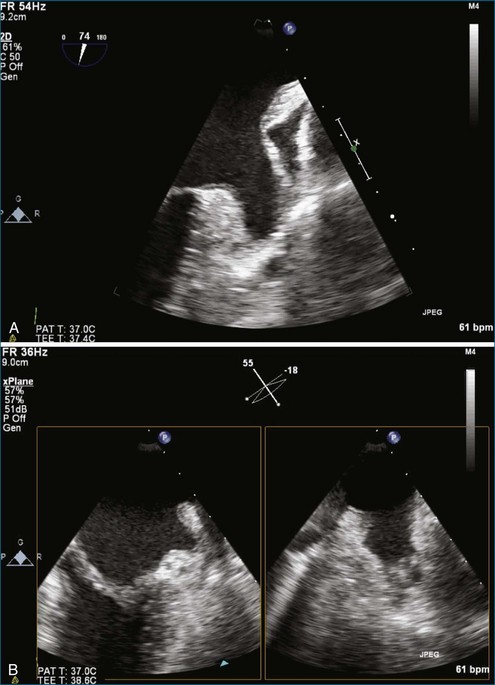

PMV is the current state-of-the-art treatment when valve morphology is favorable and mitral regurgitation is no worse than mild. Previously, Applebaum21 had suggested the use of 3DE during PMV, although this was prior to the development of RT3DE. RT3DTTE and RT3DTEE have drastically changed the approach to PMV at some centers. PMV is a unique procedure that, along with a few others, has advanced the term “interventional echocardiography” to a new level. Echocardiography guidance of PMV can be performed with either RT3DTTE or RT3DTEE. RT3DTEE, however, provides benefits to the interventional cardiologist from the transseptal puncture, to positioning the Inoue balloon, to avoiding the left atrial appendage, and finally to assessing the splitting of the commissures on both the atrial and ventricular sides of the valve. The transseptal puncture is theoretically safer using RT3DTEE guidance because of the use of biplane or “X-plane” to view two orthogonal 2D views of the septum simultaneously. Classically, the two orthogonal planes that are used are (a) the bicaval view at 110 degrees and (b) the four-chamber view at the aortic valve area, roughly 30 degrees (Figure 6-6; Video 6-12). The bicaval view guides the interventionalists to the superior portion versus the inferior portion of the septum, and the four-chamber view is useful to avoid damaging the aortic valve and root during the transseptal puncture (see Figure 6-6; Videos 6-10 to 6-12). Visualization of the fossa ovalis is also safer by RT3DTEE by both X-plane orthogonal views as well as 3D zoom mode (to visualize the entire fossa ovalis en face in real time and the catheter relationship to the superior vena cava [SVC] and the inferior vena cava [IVC] as it traverses the interatrial septum) (see Figure 6-6; Video 6-13). RT3DTEE has the advantage of providing particularly vivid images of the interatrial septum, the left atrium, the left atrial appendage, and the mitral orifice. All four of these structures are important anatomic landmarks used during the procedure, so optimal visualization also is crucial to the success or failure of the procedure.9,22,23

Although severe mitral regurgitation can be a complication of PMV, the development of some minor mitral regurgitation actually can be viewed as a sign of success. That is because the mechanism of mitral regurgitation is typically related to the splitting of the mitral commissures during the procedure.24 Further examples of RT3DTEE and RT3DTTE use during the course of PMV are shown in Figures 6-7 to 6-15 (Videos 6-14 to 6-24).

Cases

Case 2

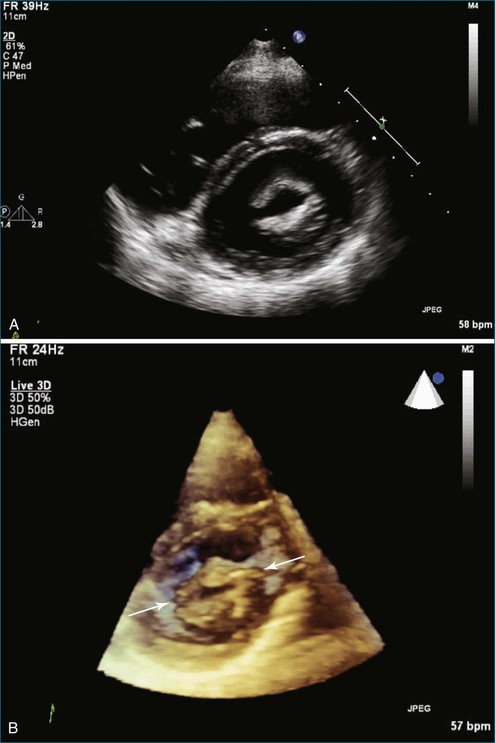

A 48-year-old woman presented to the cardiology clinic reporting the presence of a heart murmur but also having symptoms of palpitations and dyspnea. The symptoms necessitated obtaining an echocardiogram that showed moderate mitral stenosis. The patient was gravida 3 para 3 and had not had any significant problems during her pregnancy with dyspnea, palpitations, or known arrhythmia. However, her most recent pregnancy was 7 years ago. The mitral valve area was 1.2 cm2 by 3D planimetry and 1.3 cm2 by Doppler pressure half-time. Pulmonary artery pressure was 45 mm Hg but increased to 60 mm Hg with bicycle exercise. Hence, the patient was deemed a candidate for PMV. A few challenges with the procedure were clearly aided by RT3DTEE. The first was a potential thrombus in the left atrial appendage, identified using standard 2DTEE (Figure 6-16, A). However, with the use of the biplane or X-plane feature, when viewing this structure in the orthogonal plane, the structure was clearly a trabeculation of the left atrial appendage wall rather than a thrombus (see Figure 6-16, B). This also was demonstrated using the RT3DTEE mode of 3D zoom. The second was the positioning of the catheter. It was difficult to cross the valve, and use of the RT3DTEE to steer the Ionue balloon dramatically hastened the procedure (see Figures 6-10 and 6-11; see also Videos 6-17 to 6-19). After successfully navigating these potential hurdles, the procedure had a successful result, increasing the mitral valve area to 1.7 cm2 and decreasing the transmitral gradient to 5 mm Hg.

1 Veasy LG, Tani LY, Hill HR. Persistence of acute rheumatic fever in the intermountain area of the United States. J Pediatr. 1994;124:9–16.

2 Tani LY, Veasy LG, Minich LL, Shaddy RE. Rheumatic fever in children younger than 5 years: Is the presentation different? Pediatrics. 2003;112:1065–1068.

3 Meira ZM, Goular EM, Colosimo EA, Mota CC. Long term follow up of rheumatic fever and predictors of severe rheumatic valvular disease in Brazilian children and adolescents. Heart. 2005;91:1019.

4 Bono RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease. Circulation. 2006;114:e84.

5 Rahimtoola SH, Durairaj A, Mehra A, et al. Current evaluation and management of patients with mitral stenosis. Circulation. 2002;106:1183.

6 Vijayaraghavan G, Cherian G, Krishnaswami S, et al. Rheumatic aortic stenosis in young patients presenting with combined aortic and mitral stenosis. Br Heart J. 1977;39:294.

7 Davidson M, Bulkow LR, Gellin BG. Cardiac mortality in Alaska’s indigenous and non-Native residents. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:62–71.

8 Wilkins GT, Weyman AE, Abascal VM, et al. Percutaneous balloon dilatation of the mitral valve: An analysis of echocardiographic variables related to outcome and the mechanism of dilatation. Br Heart J. 1988;60:299.

9 Gill EA, Kim MS, Carroll JD. 3D TEE for evaluation of commissural opening before and during percutaneous mitral commissurotomy. J Am Coll Cardiol Imag. 2009;2:1034–1035.

10 Hernandez R, Banuelos C, Alfonso F. Long-term clinical and echocardiographic follow-up after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty with the Inoue balloon. Circulation. 1999;99:1580.

11 Lung B, Garbarz E, Michaeud P, et al. Late results of percutaneous mitral commissurotomy in a series of 1024 patients. Analysis of late clinical deterioration: Frequency, anatomic findings, and predictive factors. Circulation. 1999;99:3272.

12 Cannon CR, Nishimura RA, Reeder GS, et al. Echocardiographic assessment of commissural calcium: A simple predictor of outcome after percutaneous mitral balloon valvotomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997;29:175.

13 Chen Q, Hosir YF, Vletter WB, et al. Accurate assessment of MVA in patients with mitral stenosis by three-dimensional echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1997;10:133–150.

14 Singh V, Nanda NC, Agrawal G, et al. Live three-dimensional echocardiographic assessment of mitral stenosis. Echocardiography. 2003;20:43–50.

15 Zamorano J, Cordeiro P, Sugeng L, et al. Real-time three dimensional echocardiography for rheumatic mitral valve stenosis evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2091–2096.

16 Xie MX, Wang XF, Cheng TO, et al. Comparison of accuracy of mitral valve area in mitral stenosis by real-time, three-dimensional echocardiography versus two-dimensional echocardiography versus Doppler pressure half-time. Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:1496–1499.

17 Zamorano J, Perez de Isla L, Sugeng L, et al. Non-invasive assessment of mitral valve area during percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty: Role of real-time 3D echocardiography. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2086–2091.

18 Perez de Isla L, Casanova C, Almeria C, et al. Which method should be the reference method to evaluate the severity of rheumatic mitral stenosis? Gorline’s method versus 3D echo. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2007;8(6):470–473.

19 Mannaerts HF, Kamp O, Visser CA. Should mitral valve area assessment in patients with mitral stenosis be based on anatomical or on functional evaluation? A plea for 3D echocardiography as the new clinical standard. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:2073–2074.

20 Zamorano J, Cordeiro P, Sugeng L, et al. Real-time three-dimensional echocardiography for rheumatic mitral valve stenosis evaluation: An accurate and novel approach. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2091.

21 Applebaum RM, Kasliwal RR, Kanojia A, et al. Utility of three-dimensional echocardiography during balloon mitral valvuloplasty. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1405–1409.

22 Gill EA, Bhola R, Carroll J, et al. Three dimensional echocardiography predictors of percutaneous balloon mitral valvuloplasty success. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2001;1:S32.

23 Gill EA, Bhola R, Carroll JD, et al. Live 3D echo and biplane evaluation of mitral stenosis for prediction of mitral valvuloplasty success. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2004;17:499.

24 Kim MJ, Song JK, Song JM, et al. Long-term outcomes of significant mitral regurgitation after percutaneous mitral valvuloplasty. Circulation. 2006;114:2815.