2 Mitral regurgitation

Salient features

History

• Asymptomatic or mild symptoms: often

• Shortness of breath (from pulmonary congestion)

• Fatigue (from low cardiac output)

• Palpitation (from atrial fibrillation or LV dysfunction)

• Fluid retention (in late-stage disease)

• Obtain a history of myocardial infarction, rheumatic fever, connective tissue disorder, infective endocarditis.

Examination

• Peripheral pulse may be normal or jerky (i.e. rapid upstroke with a short duration).

• Apex beat will be displaced downwards and outwards and will be forceful in character.

• First heart sound will be soft.

• Third heart sound is common (left ventricular gallop sound).

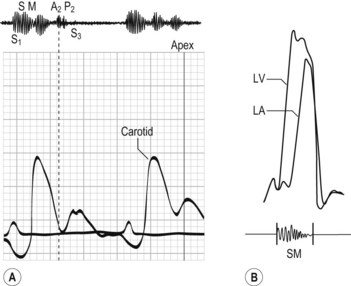

• Pansystolic murmur (Hope murmur) (Fig. 2.1) conducted to the axilla, best detected with the diaphragm and on expiration. (Note: It is important to be sure that there is no associated tricuspid regurgitation.)

• Loud pulmonary second sound and left parasternal heave when there is associated pulmonary hypertension.

Questions

How would you investigate this patient?

• ECG: look for broad bifid P waves (P mitrale), left ventricular hypertrophy, atrial fibrillation. When coronary artery disease is the cause, there is often evidence of inferior or posterior wall myocardial infarction.

• Radiography can assess pulmonary congestion, large heart, left atrial enlargement and pulmonary artery enlargement (if severe and long-standing).

• Echocardiography determines the anatomy of the mitral valve apparatus, left atrial and left ventricular size and function (typical features include large left atrium, large LV, increased fractional shortening, regurgitant jet on colour Doppler, leaflet prolapse, floppy valve or flail leaflet). The echocardiogram provides baselines estimation of LV and left atrial volume, an estimation of left ventricular ejection fraction, and approximation of the severity of regurgitation. It can be helpful to determine the anatomic cause of mitral regurgitation. In the presence of even mild tricuspid regurgitation, an estimate of pulmonary artery pressure can be obtained.

• Transoesophageal echocardiogram is useful when transthoracic echocardiography provides non-diagnostic images. It may give better visualization of mitral valve prolapse. It is useful intraoperatively to establish the anatomic basis for mitral regurgitation and to guide repair.

• Cardiac catheterization is useful to determine coexistent coronary artery or aortic valve disease. Large ‘v’ waves are seen in the wedge tracing. Left ventriculogram and haemodynamic measurements are indicated when non-invasive tests are inconclusive regarding the severity of mitral regurgitation, LV function, or the need for surgery.

How would you differentiate between mitral regurgitation and tricuspid regurgitation?

| Mitral regurgitation | Tricuspid regurgitation | |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse | Jerky or normal | Normal |

| Jugular venous pressure | Prominent ‘v’ wave | |

| Palpation | Left ventricular heave | Left parasternal heave |

| Auscultation | Pansystolic murmur | Pansystolic murmur |

| Intensity increases with expiration | Intensity increases with inspiration | |

| Radiates to the axilla | ||

| Other signs | Hepatic pulsations |

Advanced-level questions

What are the mechanisms of mitral regurgitation?

Mechanisms are grossly classified as:

• functional (mitral valve is structurally normal and disease results from valve deformation caused by ventricular remodelling), e.g. cardiomyopathy, myocarditis

• organic (intrinsic valve lesions), e.g. endocarditis, annular calcification, rheumatic heart disease, ruptured papillary muscle.

They can be subclassified by leaflet movement (Carpentier’s classification):

How would you determine the severity of the lesion?

• The larger the LV on clinical examination, the greater the severity.

• A third heart sound suggests that the disease is severe.

• Colour Doppler ultrasonography quantifies the severity of the regurgitant jet, usually into three grades. However echocardiography provides only a semiquantitative estimate of the severity of regurgitation. Left ventriculography performed during cardiac catheterization provides an additional but also imperfect estimate of the severity of mitral regurgitation.

• Prognosis is worsened if the right ventricular function is reduced and patients with a right ventricular ejection fraction of <30% are particularly at high risk (Circulation 1986;73:900–12).

How would you quantify the severity of the lesion?

Moderate mitral regurgitation:

How would you follow an asymptomatic patient with mitral regurgitation?

Mild regurgitation

What are the indications for surgery in this patient?

• Moderate to severe symptoms despite medical therapy (NYHA functional class III or IV), provided that left ventricular function is adequate.

• Patients with minimal or no symptoms should be followed up every 6 months by echocardiographic or radionuclide assessment of left ventricular size and systolic function. When the ejection fraction falls to 60% (Circulation 1994;90:830–7), or when left ventricular end systolic dimension is greater than 45 mm (J Am Coll Cardiol 1984;3:235–42), mitral valve repair or replacement should be considered even in the absence of symptoms.

• valve repair improves outcome compared with valve replacement and reduces mortality of patient with severe organic mitral regurgitation by about 70%

• ischaemic mitral regurgitation carries the worse prognosis: operative mortality is 10 to 20% and long-term survival is substantially lower than with non-ischaemic mitral regurgitation (J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1986;91:379–88, Ann Thorac Surg 1994;58:668–75).