CHAPTER 6 Miscellaneous Problems: Synovitis, Degenerative Joint Disease, and Tumors

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Synovitis

The role of arthroscopic synovectomy in treating synovial diseases was apparent to the earliest arthroscopists. In almost all pathology of the hip, synovitis is present. Our group has had several undiagnosed cases of hip pain with effusions that were shown to be seronegative rheumatoid arthritis with synovial biopsy. In 1988, Ide and colleagues1 performed arthroscopic synovectomy for RA on six hips in three patients using mechanical shavers through a two-portal technique, with good results. With the advent of laser and radiofrequency (RF) ablation, there are now three modalities used to débride the synovium. It remains difficult to reach 100% of the joint but with newer, more effective medical management, debulking of the diseased synovium seems to be adequate.

CPPD has not been reported as frequently in the hip as it has in the ligamentum flavum and in the knee, associated with RA.2,3 Our group has performed synovectomy on two patients for CPPD associated with femoroacetabular impingement. Clearly, it is an entity that should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with refractory synovitis.

There are no reports in the arthroscopic literature on the treatment of hyperlipoproteinemia, hemachromatosis, or any of the metabolic arthropathies. Our group has performed partial synovectomy in a few patients thought to have fatty deposition and in one patient with hemachromatosis associated with arthritis. It is presented here only to make the arthroscopic surgeon aware that metabolic arthropathies exist.4 Metabolic arthropathy appears as white or yellowish plaques on the articular cartilage associated with a mild synovitic reaction. The plaque cannot be removed without destroying the articular cartilage and therefore should be treated with synovectomy only.

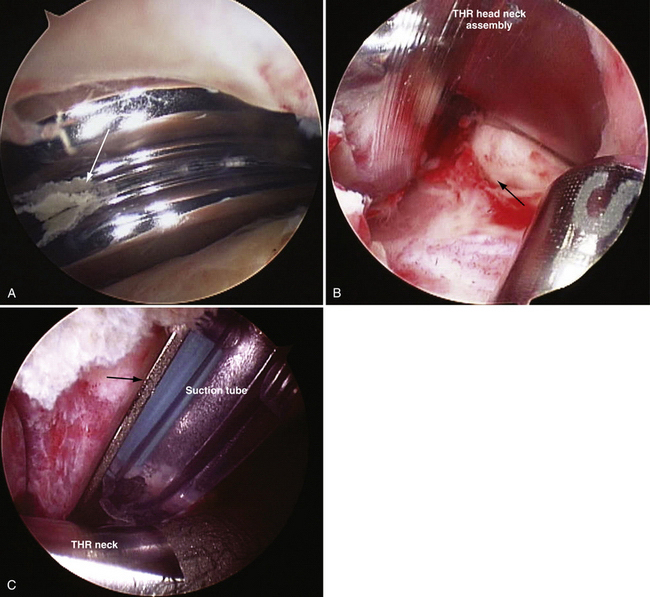

Arthroscopic débridement and lavage has become the treatment of choice for septic arthritis in children, adolescents, and adults. This modality has been associated with minimal morbidity and an excellent cure rate.5–8 McCarthy and associates9 have reported on successful treatment of septic total hips in two patients using arthroscopic débridement, lavage, and intravenous antibiotics Our group has successfully treated four patients with late hematogenous infections of their total hips arthroscopically. No recurrence has been noted, with the longest follow-up being 20 years, when one patient died from natural causes at the age of 93 years (Fig. 6-1).

Degenerative Joint Disease

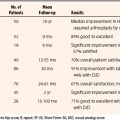

The arthroscopic treatment of degenerative joint disease (DJD) of the hip remains controversial and most challenging and difficult. Even the most experienced hip arthroscopists avoid the procedure in DJD because there are few benchmarks to predict a successful outcome. Prior to 2001, DJD was treated with arthroscopic débridement, labrectomy, synovectomy, and abrasion chondroplasty. In 28 of 290 patients who had partial labrectomies in the presence of DJD, only 21% had a good result compared with a 71% good result rate in those without DJD.10 Subsequently, with the recognition of femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) and the added correction of the abnormal morphology, the modified Harris hip score improved significantly from 72 to 92 with an average 4-year follow-up.11–13

A residual head-neck deformity from femoral neck fractures has been a cause of FAI and DJD. Reshaping of the deformity has been done using an open surgical dislocation by Eijer and coworkers.14 Our group has treated the DJD and deformity with an arthroscopic head-neck osteoplasty and débridement, synovectomy, and abrasion chondroplasty with microfracture in three patients.

Tumors

Essentially all tumors that are amenable to arthroscopic treatment are benign. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) and synovial chondromatosis may be considered synovial diseases instead of tumors, and are both difficult to eradicate unless a complete synovectomy can be performed. Frequent recurrences are seen, from inadequate removal of the tumors or inadequate synovectomy.15–17 Capsulotomy is recommended to expose all areas and recesses of the central and peripheral compartments to remove the loose and attached bodies and ablate the synovium, particularly where the lesions are forming.

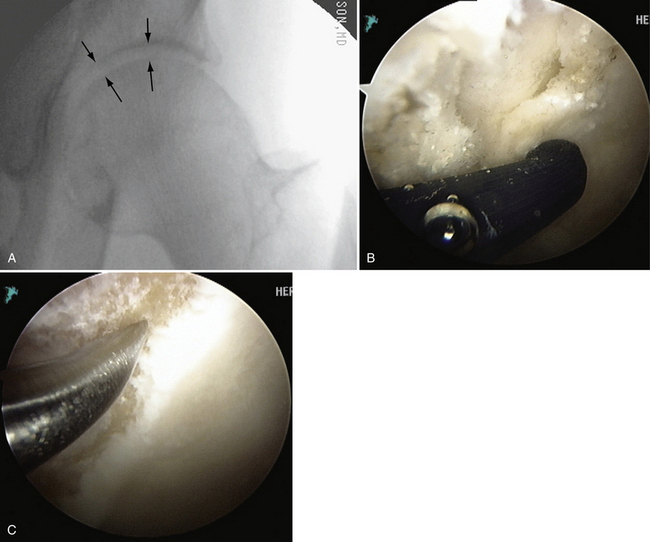

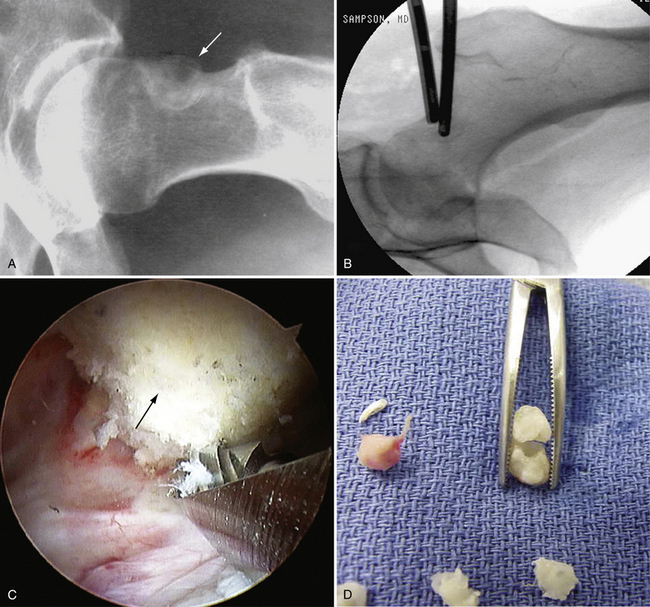

Arthroscopic removal of osteoid osteoma of the hip has been described by Glick and colleagues18 in two cases in the central compartment. Our group has since removed an old, yet active osteoid osteoma from the head-neck junction associated with a cam impingement requiring excision, synovectomy, and head neck osteoplasty (Fig. 6-2).

FIGURE 6-2 A, Radiograph of a 43-year-old woman with a 10-year history of a painful osteoid osteoma (arrow). B, Localization with fluoroscopy at surgery. C, The mass effect of the osteoid osteoma seen at arthroscopy (arrow). D, Removed osteoid osteoma, along with multiple loose bodies.

Heterotopic bone should be considered a pseudotumor of the hip and is most often a complication of trauma or hip surgery. There are no reports of its treatment using arthroscopic techniques; however, our group favors arthroscopic excision and follow surgery with a single dose of 700 rad of radiation or a strong dose of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for 3 to 6 weeks. The recurrence rate is lower with the subsequent radiation.

ANATOMY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Degenerative joint disease presents with or without a limp, and difficulty walking, sitting, and putting on shoes and socks because of restricted range of motion. With the loss of articular cartilage, a straight leg raise with the knee extended may cause pain in the groin because of the compressive forces of the opposing chondromalacic surfaces of the head and acetabulum. There may be popping and catching with rotation. Loss of internal rotation is almost always present. The Trendelenburg sign and test may be negative in milder cases. Our group has found that if there is at least 50% range of rotational movement when tested passively compared with the normal contralateral side, and if more than 50% of articular cartilage thickness on the anteroposterior (AP) x-ray is present, results show a more than 80% chance of significant improvement that continues for more than 2 years (Fig. 6-3).

Tumors present with pain and, in many cases, popping and catching. There may be a limp if there is an effusion. Range of motion may be restricted if catching or locking is present. Most patients may present with entirely normal movement. Osteoid osteomas usually cause night pain that is relieved by aspirin or other NSAIDs.18,19

PREOPERATIVE IMAGING AND PLANNING

The findings of synovitis on x-ray may be normal in the early stages may include subtle erosions and cyst formation. On MRI, the findings in RA may include subchondral erosions and hypertrophic synovium.20 DJD is easily detectable x-rays and MRI scans, with osteophyte formation and joint space narrowing. Because FAI may be the cause in many osteoarthritic hips, a metaplastic bump on the head-neck junction and a rim overgrowth or prominence may be seen. In many cases, a fibro-osseous cyst of varying size appears on the neck, typically within the bump. The MRI shows capsular thickening, chondral erosions, and usually some cysts.

TECHNIQUE

Procedure

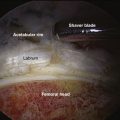

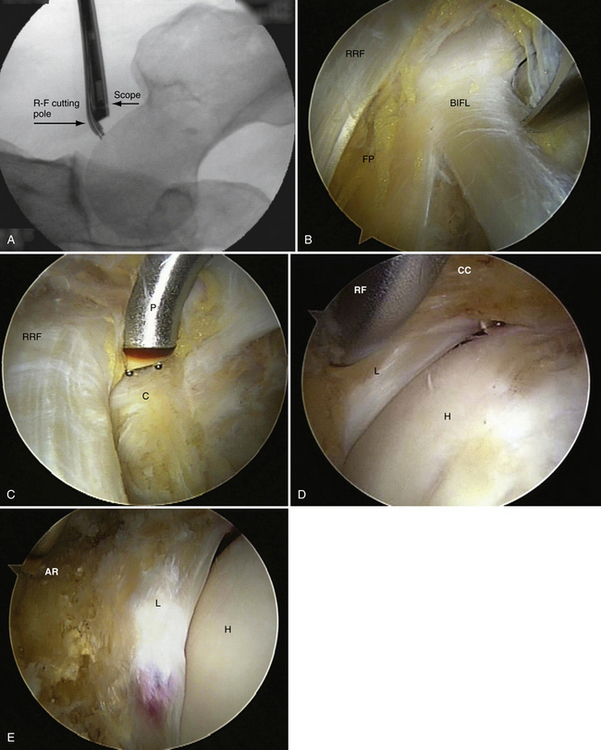

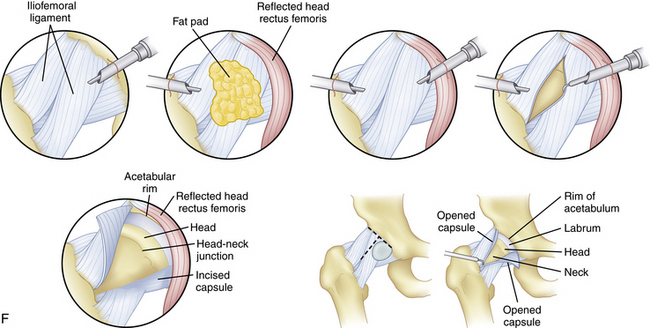

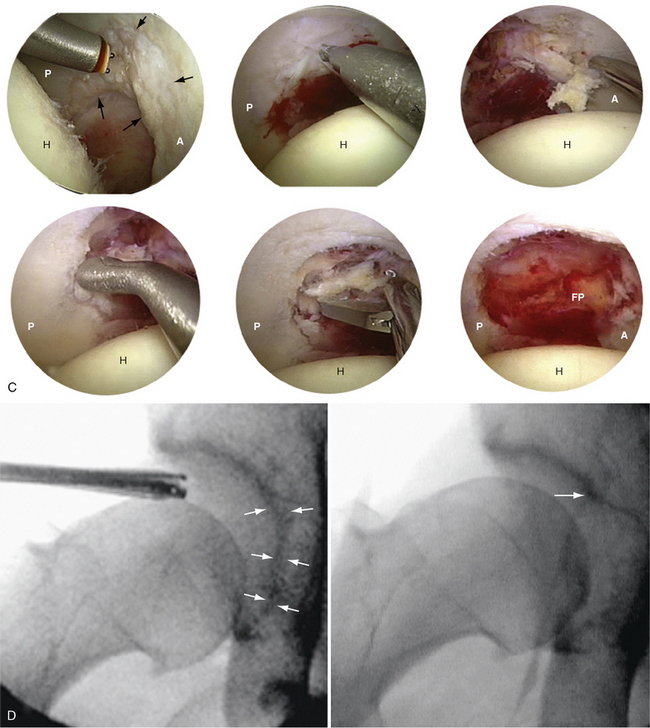

Under fluoroscopic control, the long needle is placed through the anterolateral portal directed toward the capsular area at the head-neck junction. There should be about 1 cm of clearance with the greater trochanter. A Nitinol wire is placed through the needle and the skin is incised with a no. 11 blade. The arthroscope trocar sheath assembly is pushed over the wire and the sheath is used to sweep the muscle away from the capsule. The procedure is begun with a 30-degree arthroscope. The pump is started at 50 mm Hg pressure on low flow, allowing a view of the fat pad over the anterior hip capsule. The anterior portal is established with the same technique and a 4-mm switching stick is used to sweep the capsule and palpate the reflected head of the rectus femoris. The key to this approach is identifying the rectus femoris, because the capsule directly beneath covers the anterolateral portion of the labrum (Fig. 6-4).

FIGURE 6-4 A, C-arm fluoroscopic view of the arthroscope and RF probe over the anterolateral capsule of a left hip before capsulotomy. B, Arthroscopic view external to the left anterolateral hip capsule. Note the reflected head of the rectus femoris (RRF), fat pad over the capsule (FP), and band of the iliofemoral ligament (BIFL). C, Arthroscopic view external to the left anterolateral hip capsule with the RF probe in place that matches the fluoroscopic view in A before capsulotomy. Note the RRF, capsule (C), and RF probe (P). D, Arthroscopic view of the cut capsule (CC), with the RF probe retracting the capsule before incising it over the labrum (L). Note the femoral head (H). E, Arthroscopic view of the completed capsulotomy exposing the femoral head (H), labrum (L), and acetabular rim (AR), much like what is seen in an arthrotomy. F, Illustration of the capsule being incised using the RF probe and exposure of the head-neck junction and labrum.

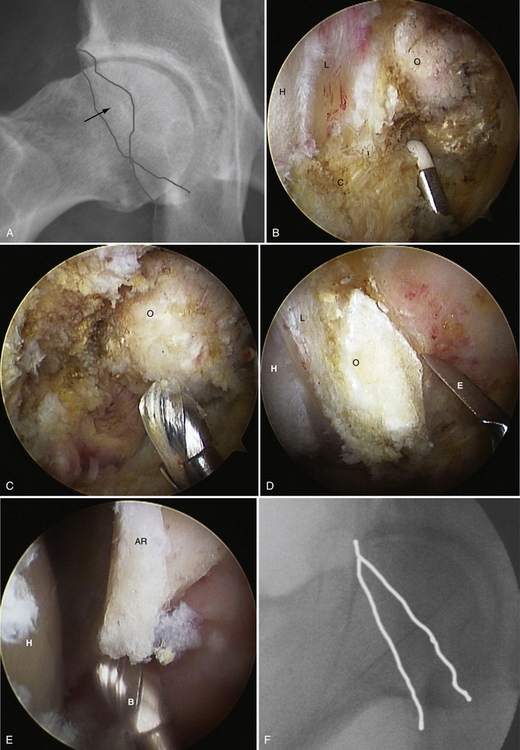

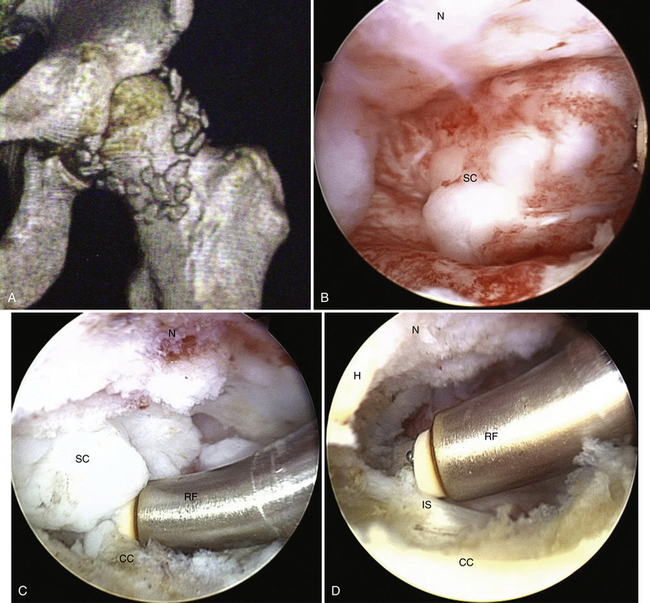

Synovitis, loose bodies, degenerative tissue, and normal and abnormal anatomy of the head-neck region are visualized similar to an open procedure with the addition of magnification (Fig. 6-5).

FIGURE 6-5 A, Three-dimensional CT scan of the left hip with synovial chondromatosis. B, Arthroscopic view of a clump of synovial chondromata (SC) anterior to the femoral neck (N). C, Arthroscopic view of a clump of SC anterior to the femoral neck (N) being freed up before extraction with an RF probe (RF). Note the cut capsule (CC). D, Arthroscopic view anterior to N in which the mass has been removed, exposing the iliopsoas (IS); the RF is being used to do a synovectomy. Note the femoral head (H).

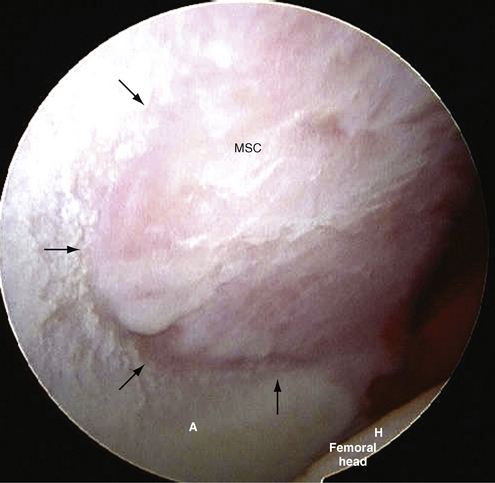

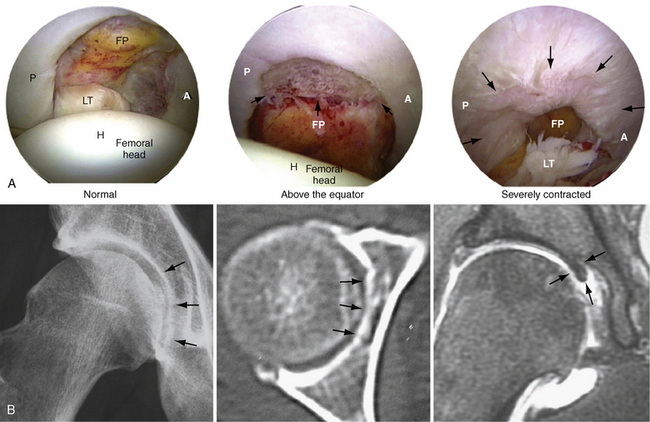

If loose bodies are present, they are removed with a shaver and graspers. Occasionally, the fat pad hides notch bodies or is fibrotic, and is removed with the shaver. If the notch is filled with a mat of chondromata, the mass is removed with a combination of curettes, picks, and shavers (Fig. 6-6). If the notch has encroaching osteophytes, osteophytectomy using a long 4-mm hip burr, curettes, and picks is preferable to restore the contact forces between the head and acetabular cartilage (Fig. 6-7).21

FIGURE 6-6 View of matted mass of synovial chondromata (MSC) filling the acetabular fossa. Note the acetabulum (A) and femoral head (H).

FIGURE 6-7 A, Arthroscopic views of the acetabular fossa from normal to arthritic. Note the head (H), ligamentum teres (LT), fat pad (FP), and anterior (A) and posterior (P) views. B, AP radiograph (A) of the fossa osteophyte, and CT (B) and MRI (C) scans. Note the notch osteophyte (arrows). C, Arthroscopic procedure for excision of a notch osteophyte. D, AP fluororadiographs before and after removal of the notch osteophyte (arrows).

The rim of the acetabulum may have an anterolateral osteophytic ridge. The osteophyte is exposed behind the labrum and removed with a 4-mm hip burr. If cysts are encountered, they are curetted and saucerized with the burr (Fig. 6-8).

Erosions of the articular cartilage of the head and acetabulum require excision of the delaminated tissue to stable cartilage with a shaver or curette, abrasion and removal of the calcific layer, and microfracture using the awls. Most areas can be reached on the acetabular surface except for zone 6, near the transverse ligament; however, on the femoral head, there is difficulty applying instruments to zones 2m, 3m, 4m, and 6.22

If the hip is arthritic and stiff, a generous capsulectomy is done with the 5-mm shaver, arthroscopic knife, and/or RF probe. In all other situations, the capsule is left open, because it will heal in most cases (Fig. 6-9).

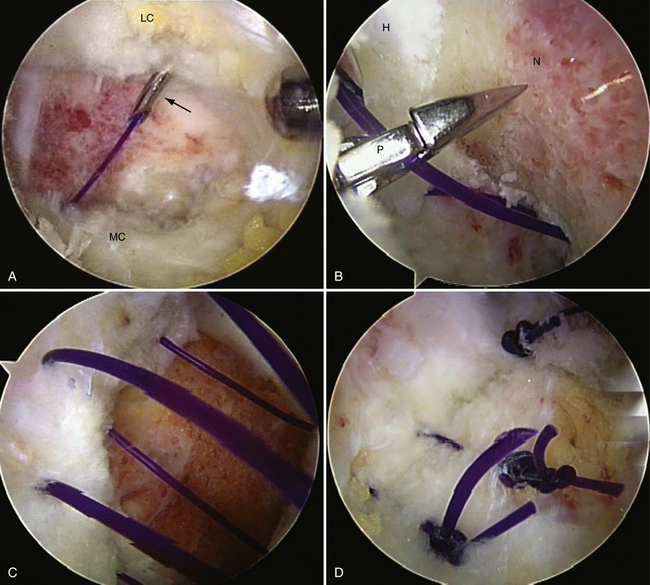

FIGURE 6-9 A, Arthroscopic view of a capsular closure of a left hip. The curved suture hook (arrow) is shown penetrating the lateral capsule (LC) with a no. 1 absorbable monofilament suture. Note the medial capsule (MC). B, Arthroscopic view of a capsular closure of a left hip showing the penetrator (P) grasper grabbing the suture. Note the head (H) and neck (N) of the femur. C, Arthroscopic view of a capsular closure of a left hip after a no. 3 suture has been passed before tying. D, Arthroscopic view of a capsular closure of a left hip after the sutures have been tied and the capsule closed.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

After wound closure, 30 mL of bupivacaine is administered to all patients. An NSAID such as ibuprofen, celecoxib, or diclofenac is prescribed to reduce the potential for heterotopic bone formation. On the day of surgery, weight bearing on two crutches is begun as tolerated and progressed to one crutch or a cane. When the patient is experiencing little pain on weight bearing, has no sensation of giving way, and has good hip stabilization, use of the crutches or cane can be discontinued. Beginning 1 day after surgery, or when tolerated, the patient is encouraged to ride a stationary bike with little to no resistance for 20 minutes three times daily. The time is increased along with the resistance as tolerated. Sutures are removed at 1 week and elliptical and weight-training exercises are begun, along with distance walking on a treadmill or outside. The patient is taught range of motion exercises and told not to hyperextend for 3 to 6 weeks. At 1 month, the patient is evaluated for symptoms, range of motion, and hip stability. Most patients continue with self-directed advancement of their exercises and activities. If the range of motion is not 80% of normal, physical therapy is advised. Symptoms may continue to some degree, even after successful surgery, for at least 1 year, and patients are advised not to be alarmed if the symptoms fluctuate in intensity and frequency. Most symptoms improve over months. If there is a significant decline, further investigation with a simple x-ray may lead to a diagnosis of failed surgery. Surgical failure in arthritic patients is demonstrated by further loss of joint space or widening of the medial clear space and superior lateral subluxation.

COMPLICATIONS

In our series of 1000 cases, we have found that continuous distraction lasting less than 2 hours results in no sciatic, femoral, or pudendal neuropraxias. We have had five cases of lateral cutaneous neuropraxia; however, all either resolved or the patient accommodated to the patch of numbness on the thigh. Approximately 1% of our cases developed heterotopic bone; in five patients, reoperation was required to alleviate symptoms. There was one nondisplaced femoral neck fracture in a patient treated for DJD and FAI, in which the treatment was placement of a single cannulated screw. This patient has had a final modified Harris hip score of 100 for the last 5 years. We have had no occurrence of deep infections.

1. Ide T, Akamatsu N, Nakajima I. Arthroscopic surgery of the hip joint. Arthroscopy. 1991;7:204-211.

2. Ishida Y, Oki T, Ono Y, Nogami H. Coffin-Lowry syndrome associated with calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition in the ligamenta flava. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;275:144-151.

3. Gerster JC, Varisco PA, Kern J, et al. CPPD crystal deposition disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2006;25:468-469.

4. Timsit MA, Bardin T. Metabolic arthropathies. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1994;6:448-453.

5. Broy SB, Schmid FR. A comparison of medical drainage (needle aspiration) and surgical drainage (arthrotomy or arthroscopy) in the initial treatment of infected joints. Clin Rheum Dis. 1986;12:501-522.

6. Ohl MD, Kean JR, Steensen RN. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritic knees in children and adolescents. Orthop Rev. 1991;20:894-896.

7. Blitzer CM. Arthroscopic management of septic arthritis of the hip. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:414-416.

8. Kim SJ, Choi NH, Ko SH, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of septic arthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;407:211-214.

9. McCarthy JC, Jibodh SR, Lee JA. The role of arthroscopy in evaluation of painful hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:174-180.

10. Farjo LA, Glick JM, Sampson TG. Hip arthroscopy for acetabular labral tears. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:132-137.

11. Sampson T. Hip morphology and its relationship to pathology: dyplasia to impingement. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2005;13:37-45.

12. Sampson T. Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement. Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2005;20(1):56-62.

13. Sampson TG. Arthroscopic treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: a proposed technique with clinical experience. Instr Course Lect. 2006;55:337-346.

14. Eijer H, Myers SR, Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement after femoral neck fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2001;15:475-481.

15. Boyer T, Dorfmann H. Arthroscopy in primary synovial chondromatosis of the hip: description and outcome of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:314-318.

16. Sim FH. Synovial proliferative disorders: role of synovectomy. Arthroscopy. 1985;1:198-204.

17. Yamamoto Y, Hamada Y, Ide T, Usui I. Arthroscopic surgery to treat intra-articular type snapping hip. Arthroscopy. 2005;21:1120-1125.

18. Khapchik V, O’Donnell RJ, Glick JM. Arthroscopically assisted excision of osteoid osteoma involving the hip. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:56-61.

19. Alvarez MS, Moneo PR, Palacios JA. Arthroscopic extirpation of an osteoid osteoma of the acetabulum. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:768-771.

20. Sampson T, Bredella M. The hip. In: Stoller DW, editor. Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:41-304.

21. Daniel M, Iglic A, Kralj-Iglic V. The shape of acetabular cartilage optimizes hip contact stress distribution. J Anat. 2005;207:85-91.

22. Ilizaliturri VMJr, Byrd JW, Sampson TG, et al. A geographic zone method to describe intra-articular pathology in hip arthroscopy: cadaveric study and preliminary report. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:534-539.