Chapter 11 Miscarriage and abortion

AETIOLOGY OF SPONTANEOUS MISCARRIAGE

The causes of miscarriage are:

Implantation

In the early weeks of pregnancy (0–10 weeks) ovofetal factors account for most miscarriages; in the later weeks (11–22 weeks) maternal factors become more common (Table 11.1).

| FACTOR | PERCENTAGE |

|---|---|

| Fetal or ovular | |

| Defective ovofetus | 60 |

| Defective implantation or activity of trophoblast | 15 |

| Maternal | |

| General disease | 2 |

| Uterine abnormalities | 8 |

| Psychosomatic | ?15 |

Maternal factors

Systemic maternal disease (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus), and particularly maternal infections, account for 2% of miscarriages. A further 8% are associated with uterine abnormalities, such as congenital defects, uterine myomata, particularly submucous tumours, or cervical incompetence (see p. 104). Psychosomatic causes have been suggested as leading to miscarriage, but the evidence is difficult to evaluate. Women who smoke 10 cigarettes or more per day double their risk.

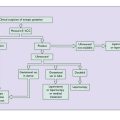

VARIETIES OF SPONTANEOUS MISCARRIAGE

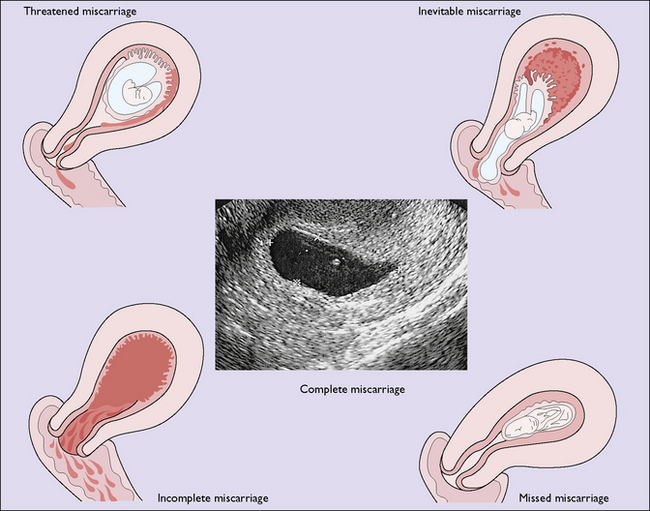

For descriptive purposes the miscarriage is classified according to the findings when the woman is first examined, but one kind may change into another if the aborting process continues. If infection complicates the miscarriage, the term septic miscarriage is used. The various types of miscarriage are shown in Figure 11.1 and each will be considered separately later.

Threatened miscarriage

A real-time pelvic ultrasound examination will clarify the diagnosis. This may show:

Inevitable, incomplete and complete miscarriage

Treatment

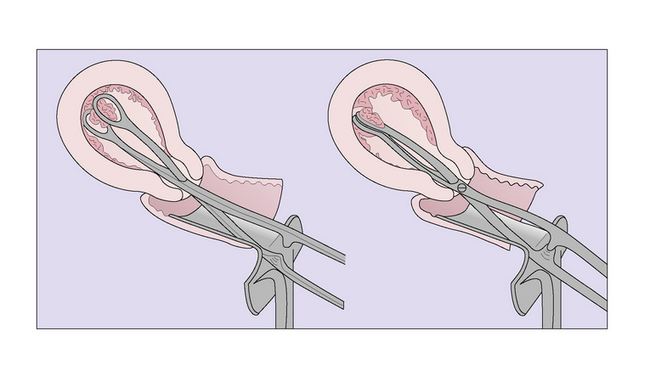

If there is any doubt about the completeness of the miscarriage the patient should be taken to the operating theatre and the uterus evacuated using a sponge forceps (Fig. 11.2), followed by a careful suction curettage. Towards the end of the curettage, an injection of ergometrine 0.25 mg is given intravenously.

Missed miscarriage/abortion

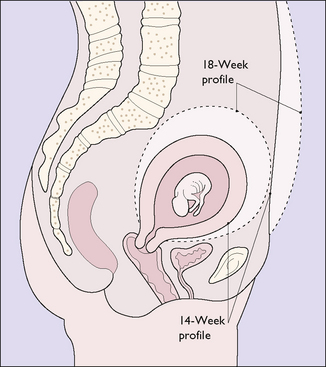

In a few cases of miscarriage the dead embryo or fetus and placenta are not expelled spontaneously. If the embryo dies in the early weeks it is likely to be anembryonic or blighted. In other cases a fetus forms but dies. Multiple haemorrhages may occur in the choriodecidual space, which bulge into the empty amniotic sac. This condition is called a carnaceous mole. It is thought that although the fetus has died, progesterone continues to be secreted by surviving placental tissue, which delays the expulsion of the products of conception (Fig. 11.3).

If the fetus dies at a later stage of the pregnancy, but before the 22nd gestational week, and is not expelled, it is either absorbed or mummified. The liquor amnii is absorbed and the placenta degenerates. Fetal death after the 22nd week is discussed on page 203.

Clinical aspects

With the widespread use of ultrasound a common presentation is at the time of a routine ultrasound examination when a fetal heart is not detected. Alternatively the woman may report that she has had a small amount of vaginal bleeding and this may be accompanied by the disappearance of early pregnancy symptoms (Fig. 11.3).

Treatment

There is no medical need to treat missed miscarriage urgently as most cases end in a spontaneous miscarriage. Information and support must be given to the parents once they become aware that the fetus has died in utero, as this can be a very traumatic experience. In most cases the woman requests an early evacuation of the uterus. Surgical evacuation when the uterine size is greater than 12–14 weeks’ gestational size carries greater risk of haemorrhage and uterine and cervical damage and this must be explained. In these cases if the woman does not want to wait for spontaneous miscarriage then termination is best effected using mifepristone and misoprostol or prostaglandins, as described on page 106.

Recurrent (habitual) miscarriage

The aetiological factors in recurrent miscarriage vary depending on the population studied, but two large series, of over 100 subjects in each, offer some idea of the aetiology (Table 11.2). In Table 11.2 the causes marked with a query are speculative.

| POSSIBLE AETIOLOGY | PERCENTAGE OF MISCARRIAGES OCCURRING | |

|---|---|---|

| <12 weeks | >12 weeks | |

| Not known | 62 | 35 |

| Uterine malformations or abnormality | 3 | 10 |

| Cervical incompetence | 3 | 30 |

| Chromosome abnormality | <5 | <4 |

| ?Endometrial infection | 15 | 15 |

| Endocrine dysfunction | 3 | 3 |

| Systemic disease | 1 | 1 |

| ?Sperm factors | 3 | 1 |

| ?Immune factors | ? | 1 |

Investigation and treatment of a recurrent miscarrier

Endocrine dysfunctions, for example polycystic ovarian disease (see p. 223), may be excluded by transvaginal ultrasound scanning and blood tests. Other endocrine disorders, such as thyroid disease and diabetes, are no longer believed to be causes of recurrent miscarriage unless they are poorly controlled.

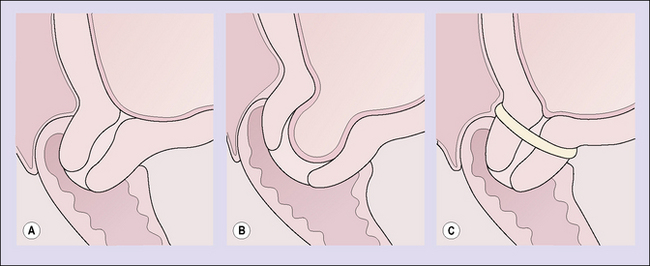

Cervical incompetence

If cervical incompetence is diagnosed, treatment entails placing a soft unabsorbable suture (such as Mersilk 4) around the cervix at the level of the internal cervical os (Fig. 11.4). The patient may return home the same night or stay in hospital for a day, depending on the circumstances. There is no place postoperatively for the use of progesterone, uterine relaxants or narcotics. If there is doubt about the diagnosis, then surveillance with ultrasound is undertaken, cerclage being performed if there are signs of cervical shortening and/or beaking of the membranes through the internal os.

INDUCED ABORTION

The main reasons for abortion are shown in Box 11.1. In most developed countries where abortion is legal, over 95% are performed for social or psychiatric reasons. It should be stressed that women rarely seek an abortion without considerable thought, and are receptive to and welcome counselling during this difficult time. It is also evident that in many cases the pregnancy could have been prevented if effective contraceptive precautions had been taken.

Technique of induced abortion

After the 12th gestational week the uterus may be evacuated using the following: