Chapter 57 Minor Trauma

1 What are the major considerations in wound assessment?

Local factors include location, mechanism of injury, wound age, possibility of foreign body, and degree of contamination. Soil contamination with organic matters has the highest rate of wound infection if not properly cleansed. The possibility of a retained foreign body should be entertained in wounds caused by broken glass or other debris. Imaging studies should be obtained if a foreign body is suspected.

Local factors include location, mechanism of injury, wound age, possibility of foreign body, and degree of contamination. Soil contamination with organic matters has the highest rate of wound infection if not properly cleansed. The possibility of a retained foreign body should be entertained in wounds caused by broken glass or other debris. Imaging studies should be obtained if a foreign body is suspected.

Host factors include disease states, tetanus immunization, allergies, sedation, and pain control.

Host factors include disease states, tetanus immunization, allergies, sedation, and pain control.

2 How does location of injury affect assessment?

Injuries over a joint or adjacent to tendons should be checked for crepitus, which may signify disruption of the joint capsule. Loss of function may indicate tendon injury.

Injuries over a joint or adjacent to tendons should be checked for crepitus, which may signify disruption of the joint capsule. Loss of function may indicate tendon injury.

Lacerations close to the neurovascular bundle are at risk for nerve damage. Assess capillary refill and pulses and conduct a careful neurologic examination of motor and sensory functions.

Lacerations close to the neurovascular bundle are at risk for nerve damage. Assess capillary refill and pulses and conduct a careful neurologic examination of motor and sensory functions.

Wounds in proximity to areas of high bacterial concentration, such as the perineum, axilla (particularly in adolescents), and exposed parts (hands, feet) are at a higher risk for infection.

Wounds in proximity to areas of high bacterial concentration, such as the perineum, axilla (particularly in adolescents), and exposed parts (hands, feet) are at a higher risk for infection.

10 When should a consultation be obtained for wound care?

Consider consultation with a surgical or orthopedic specialist for wounds associated with:

14 When should a retained foreign body be removed?

Location: Intra-articular, intravascular, or in close proximity to vital structures or has the potential to migrate towards vital structures (e.g., lung, spleen)

Location: Intra-articular, intravascular, or in close proximity to vital structures or has the potential to migrate towards vital structures (e.g., lung, spleen)

Material: Risk of toxicity (e.g., lead, venom from spines)

Material: Risk of toxicity (e.g., lead, venom from spines)

Tissue response: Production of inflammatory response (e.g., organic matter, silica that causes large granuloma formation), persistent pain, infection, or cosmetic disfigurement

Tissue response: Production of inflammatory response (e.g., organic matter, silica that causes large granuloma formation), persistent pain, infection, or cosmetic disfigurement

21 How can the pain of infiltration of a local anesthetic be decreased?

The pain of infiltration can be decreased by:

Prior application of LET gel (time permitting)

Prior application of LET gel (time permitting)

Rubbing the skin near the site of injection (stimulates other nerve endings and thereby decreases the perception of pain)

Rubbing the skin near the site of injection (stimulates other nerve endings and thereby decreases the perception of pain)

Buffering lidocaine with 8.4% sodium bicarbonate (ratio, 9:1)

Buffering lidocaine with 8.4% sodium bicarbonate (ratio, 9:1)

Warming the buffered lidocaine to 40 °C

Warming the buffered lidocaine to 40 °C

22 What is the best method of obtaining hemostasis during wound repair?

24 What are the appropriate types of sutures and techniques for closure of various wounds?

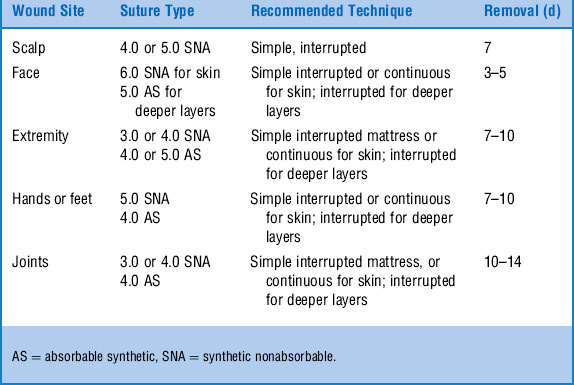

For skin closure, synthetic nonabsorbable, monofilament nylon (Ethilon or Dermalon) should be used. Fine absorbable synthetic sutures (e.g., coated Vicryl or Dexon) are used for deeper layers or nail-bed repairs. Suture size depends on the site and size of the wound. Smaller needles (e.g., PS or P1) are used for wounds that require fine cosmetic outcome. Table 57-1 lists suggested suture types for various locations.

29 A 10-year-old boy presents with persistent pain in his right forefoot after sustaining a puncture wound from a nail 10 days ago. Some redness and swelling are seen at the site. What are your major concerns and management course?

36 Describe the proper approach to lacerations of the tongue and buccal mucosa

Small isolated lacerations of the buccal mucosa, usually due to teeth impaction after falls, require no suturing. Lacerations > 2–3 cm in length or with flaps are best closed with simple interrupted stitches using absorbable material.

Small isolated lacerations of the buccal mucosa, usually due to teeth impaction after falls, require no suturing. Lacerations > 2–3 cm in length or with flaps are best closed with simple interrupted stitches using absorbable material.

Tongue lacerations often bleed excessively at the time of injury, but the bleeding usually ceases quickly as the lingual muscle contracts. Most tongue lacerations can be left alone with good results. Large lacerations involving the free edge, large flaps, and bleeding lacerations should be repaired. Full-thickness repair with interrupted 4–0 absorbable sutures is recommended.

Tongue lacerations often bleed excessively at the time of injury, but the bleeding usually ceases quickly as the lingual muscle contracts. Most tongue lacerations can be left alone with good results. Large lacerations involving the free edge, large flaps, and bleeding lacerations should be repaired. Full-thickness repair with interrupted 4–0 absorbable sutures is recommended.

Local or regional anesthesia is often sufficient.

Local or regional anesthesia is often sufficient.

Attention must be paid to potential airway problems during repair.

Attention must be paid to potential airway problems during repair.

The mouth should be held open with a padded tongue depressor. The tongue can be maintained in the protruded position by a gentle pull by using a towel clip or by placing a suture through the tip.

The mouth should be held open with a padded tongue depressor. The tongue can be maintained in the protruded position by a gentle pull by using a towel clip or by placing a suture through the tip.

As in lip lacerations, children may chew off the stitches; parents must be warned of this possibility. They should attempt to distract the child, at least until the local anesthesia has worn off.

As in lip lacerations, children may chew off the stitches; parents must be warned of this possibility. They should attempt to distract the child, at least until the local anesthesia has worn off.

39 How should a subungal hematoma be managed?

Subungual hematoma (Fig. 57-1) is a collection of blood in the interface of the nail and nail bed. It is commonly seen with blunt fingertip injuries. The usual presentation is throbbing pain and discoloration of the nail. Subungual hematoma may be associated with nail bed injury or fracture of the distal phalanx. A subungual hematoma involving 50% or more of the nail should be drained. Drainage of the hematoma relieves symptoms. In general, no local anesthesia is required for a simple trephination by cauterization of the nail. Postdrainage care includes elevation of the hand and warm soaks for a few days. The possibility of nail deformity in the future should be discussed with the family.

42 What are the key elements of postrepair wound care?

Apply antibiotic cream to reduce infection by preventing scab formation.

Apply antibiotic cream to reduce infection by preventing scab formation.

Elevate the affected area to decrease edema.

Elevate the affected area to decrease edema.

Immobilize wounds over joints with a splint or apply a bulky dressing.

Immobilize wounds over joints with a splint or apply a bulky dressing.

Provide discharge instructions regarding wound care, signs of infection, and follow-up.

Provide discharge instructions regarding wound care, signs of infection, and follow-up.

Instruct patient to avoid bathing for 24–48 hours; after that time, the wound should be washed with mild soap and water and gently dried.

Instruct patient to avoid bathing for 24–48 hours; after that time, the wound should be washed with mild soap and water and gently dried.

Recheck patient in 24–48 hours for healing and signs of infection.

Recheck patient in 24–48 hours for healing and signs of infection.

Remove sutures in a timely manner to prevent scars from suture tracks.

Remove sutures in a timely manner to prevent scars from suture tracks.

Instruct patient to use sunscreen for 6–12 months after injury to prevent hyperpigmentation of the scar.

Instruct patient to use sunscreen for 6–12 months after injury to prevent hyperpigmentation of the scar.

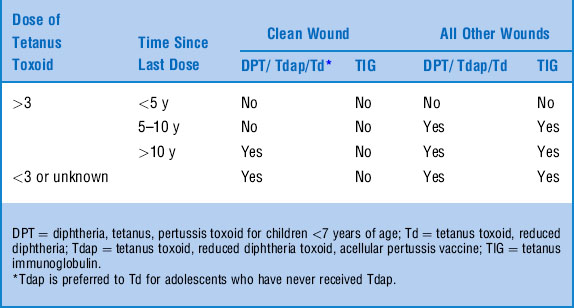

44 What are the indications for tetanus prophylaxis?

Tetanus is a potential risk in all wounds. Wounds at a higher risk for tetanus are those contaminated by soil or feces and those with devitalized tissue (e.g., puncture, crush, missile, or avulsion wounds). Burns and frostbite are also prone to tetanus. Prophylaxis depends on the type of wound and the patient’s immunization status (Table 57-3).

45 A young boy is brought to the ED after being stuck by a needle on the playground. The needle has crusted blood along the metallic edge. What are your concerns? What is the best course of management?

A needlestick injury raises concerns about exposure to tetanus and blood-borne pathogens, such as hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). HBV can survive on fomites for several days. Table 57-4 summarizes the American Academy of Pediatrics Red Book recommendations for hepatitis prophylaxis after a needlestick exposure.

Table 57-4 Hepatitis Prophylaxis After a Needlestick Exposure

| Number of Doses of HBV Vaccine Already Received | Immunoprophylaxis |

|---|---|

| >3 | None |

| 1–3 | Additional dose of HBV vaccine; complete the rest of the schedule with or without HBIG |

| None | Begin vaccination series + HBIG |

HBIG = hepatitis B immunoglobulin, HBV = hepatitis B.

American Academy of Pediatrics: Red Book Online: http://aapredbook.aappublications.org

46 When is rabies prophylaxis indicated?

Various animals transmit rabies. The virus is shed in the saliva of infected animals for 10–14 days before they become symptomatic. Postexposure guidelines are summarized in Table 57-5.Bites from animals such as squirrels, hamsters, guinea pigs, gerbils, chipmunks, rats, mice, rabbits, hares, and other rodents rarely require rabies prophylaxis.

| Type of Animal | Availability of Animal for Observation | Postexposure Prophylaxis |

|---|---|---|

| Dog or cat | Healthy or can be observed for 10 d Suspected to be rabid or unknown |

Only if animal develops signs of rabies RIG + HDCV |

| Livestock, ferrets, rodents | Consider individually | As per advice of public health official |

| Skunks, raccoons, bats, fox, woodchuck, other carnivores | Consider rabid unless geographic area is known to be free of rabies | RIG + HDCV |

HDCV = human diploid cell vaccine, RIG = rabies immunoglobulin.

American Academy of Pediatrics: Red Book Online: http://aapredbook.aappublications.org