MINOR BRUISES AND WOUNDS

BRUISES

Never attempt to puncture or cut into a bruise to drain it. This is fraught with the risk of uncontrolled bleeding and the introduction of bacteria that cause infection. The exception to this rule is a tense and painful collection of blood under the fingernail (see page 258).

A severe bruise, usually caused by a direct blunt force, can on rare occasion develop into a compartment syndrome (see page 73).

BLACK EYE

A black eye is a darkened blue or purple discoloration in the region around the eye. It can be caused by a direct blow (bruise) or by blood that has settled into the area from a broken nose, skull fracture, or laceration of the eyebrow or forehead. “Raccoon eyes” are black eyes caused by a skull fracture. If a black eye is due to a direct injury (with swelling and pain), first examine the eyeball for injury (see page 182). The skin discoloration may be treated with intermittent cold compresses for 24 hours.

BLOOD UNDER THE FINGERNAIL

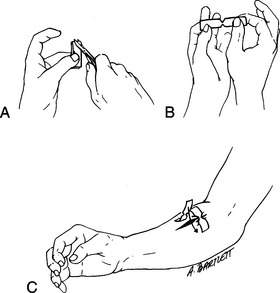

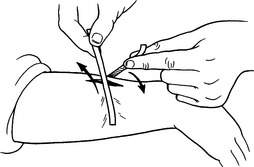

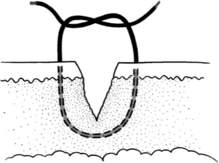

When a fingertip is smashed between two objects, there is frequently a rapid blue discoloration of the fingernail, which is caused by a collection of blood underneath the nail. Pain from the pressure may be quite severe. To relieve the pain, it is necessary to create a small hole in the nail directly over the collection of blood, to allow the blood to drain and thus relieve the pressure. This can be done during the first 24 to 48 hours following the injury by heating a paper clip or similar-diameter metal wire to red-hot temperature in a flame (taking care not to burn your fingers while holding the other end of the wire; use a needle-nose pliers, if available) and quickly pressing it through the nail (Figure 134). Another technique is to drill a small hole in the nail by twirling a scalpel blade, sharp knife, or needle. As soon as the nail is penetrated, blood will spurt out, and the pain will be considerably lessened. Before and after the procedure, the finger should be washed carefully. If the procedure was not performed under sterile conditions, administer dicloxacillin, erythromycin, or cephalexin for 3 days.

PUNCTURE WOUNDS

Puncture wounds are most frequently caused by nails, tree branches, fishhooks, and the like. Because they do not drain freely, these wounds carry a high risk for retained bacteria and subsequent infections. A puncture wound should be irrigated copiously with the cleanest solution that is available and left open to heal. Bleeding washes bacteria from the wound, so a small amount of bleeding should be encouraged. Never suture or tape a puncture wound closed, unless necessary to halt profuse bleeding; doing so promotes the development of infection. Similarly, do not occlude the opening of a puncture wound with a “grease seal” or plug of medicinal ointment; apply any antiseptic sparingly. If the wound is more than ¼ in (0.6 cm) at its opening, you can leave a piece of sterile gauze in the wound as a wick for a day or two, to allow drainage and prevent the formation of an abscess cavity (see page 241). If the wound becomes infected (see page 240), apply warm soaks four or more times a day. Treat the victim with dicloxacillin, erythromycin, or cephalexin for 4 days.

SCRAPES

The pain of cleansing can be relieved by applying pads soaked with lidocaine 2.5% ointment to the abrasion for 10 to 15 minutes before scrubbing. To avoid lidocaine toxicity, don’t do this if the surface area of the abrasion exceeds 5% of the total body surface area (an area approximately five times the size of the victim’s fingers and palm). In some cases, particularly when there is deeply embedded grime that will be extremely painful to remove, it is useful to inject the wound with a local anesthetic (see page 262).

CUTS (LACERATIONS)

1. Control bleeding. This can be done in almost every instance by direct pressure (see page 54). Apply firm pressure to the wound using a wadded sterile compress, cloth, or direct hand contact (wearing latex gloves, if possible; if you are allergic to latex, use other nonpermeable gloves, such as nonlatex synthetic). Hold the pressure for a full 10 to 15 minutes without release. If this does not stop the bleeding, apply a sterile compress and wrap with an elastic bandage, taking care to not wrap so tightly as to occlude the circulation (check for warm and pink fingers and toes). If bleeding is not controlled with pressure alone, you may need to apply a hemostatic (stops bleeding) dressing or compress. These are described on page 55. During all of these maneuvers, keep the victim calm and elevate the injured part as much as possible.

2. Clean the wound. In many cases, “the solution to pollution is dilution.” After you have controlled the bleeding, the minor wound(s) should be properly cleansed. If you have needed to use hemostatic gauze or other ancillary agent (such as Celox) other than brief pressure to control the bleeding, you should wait for at least 60 minutes before attempting to clean the wound. Otherwise, brisk bleeding may reoccur. Wear sterile, nonpermeable, nonlatex gloves if these are available; if you are not allergic to latex, latex gloves are acceptable. If sterile gloves are not available, wear nonsterile gloves. Examine the wound and remove all obvious foreign debris.

3. Anesthetize (numb) the wound. Most laypeople will never be called on to sew (suture) or staple a wound closed. However, for the benefit of rescuers who might need to practice advanced skills, here are the basics:

SKIN FLAPS AND AVULSIONS

If a cut occurs at an oblique angle to the skin, so that a very thin layer of skin is “shaved” away, the wound should be cleaned carefully and the flap repositioned and held in place with tape (see below). If the flap is extremely thin or if its base of attachment is small, the blood supply may not be sufficient to allow survival of the tissue. In this circumstance, it will turn dusky blue and then blacken, harden, shrivel, and fall away. Unless there is an underlying infection—in which case the obviously dead or dying tissue should be removed—the flap may provide a biologic covering, much like a skin graft, to allow the underlying tissue to proliferate and heal. Since it is difficult to tell which dusky flaps will survive and turn pink and which will deteriorate and “mummify,” it is best to give the flap at least a few days before trimming to see which way things are headed.

If a large chunk of skin is cut away entirely, or avulsed, the wound must either be closed, allowed to fill in as it heals with new tissue, or covered with a skin graft. The first two options are available to you in the field. If fat or muscle is showing and the wound edges will not easily pull together for field closure, the wound should be cleaned carefully, a sterile bandage (see below) applied, and the victim transported to definitive medical care.

TAPING A WOUND CLOSED

To apply tape to a wound, prepare the skin surrounding the cut by drying it thoroughly. Next, apply a thin layer of tincture of benzoin using a cotton-tipped swab, taking care not to get any into the open wound (it will sting like crazy). Push the two sides of the wound together so that they are perfectly opposed, and then lay the first adhesive strip across the wound at the midpoint of its length. Continue to apply strips perpendicular to the long axis of the wound until it is closed. Use diagonal or crisscross strips for extra strength.

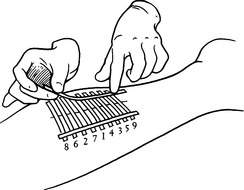

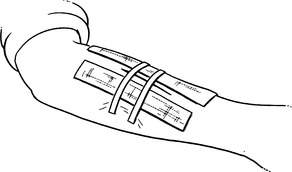

If you don’t have an assistant and it is difficult to hold the wound edges together and lay down an adhesive strip at the same time, you can fix a strip to one side of the wound, fix a second strip immediately next to the first one on the opposite side, and then use the two loose ends to pull the wound together (Figure 142). If the strips keep popping off the skin because it is slippery or too much tension is required to keep the edges together, you can run a strip of adhesive tape or duct tape longitudinally along the wound edges on either side of the gash about ¼ in (0.6 cm) away from the opening, and use these as anchors for the crossing strips (Figure 143).

Another method of wound closure using tape, which may be more appropriate for a longer wound, is to cut two strips of adhesive tape 1 in (2.5 cm) longer than the wound. Fold one-quarter of each strip of tape over lengthwise (sticky to sticky) to create a long nonsticky edge on each piece (Figure 144). Attach one strip of the tape on each side of the wound, ¼ in to ½ in (0.6 to 1.3 cm) from the wound, with the folded (nonsticky) edge toward the wound. Using a needle and thread, sew the folded edges together, cinching them tightly enough to bring the wound edges together properly (Figure 145). The tape will stick much better if you first apply a thin layer of benzoin to the skin.

SEWING (SUTURING) A WOUND CLOSED

In general, it is best to avoid sewing (suturing) a wound closed outside of the sterile environment of the hospital. However, sometimes this is necessary, particularly if the wound is large and cannot be closed with taping methods.

Sutures come in a variety of sizes attached to many different types of needles, depending on their purpose. For an expedition kit intended for use by a layperson, I recommend carrying 3/O monofilament nylon suture (such as Ethilon, Dermalon, or Prolene) attached (“swaged on”) to a large curved “cutting” needle, and 4/O monofilament nylon suture attached to a large curved cutting needle. The 3/O suture is larger in diameter, and should be used to close large wounds on the scalp, trunk, and limbs. The smaller-diameter 4/O suture is used to close smaller wounds on the trunk, limbs, hands, and feet. Although there are other suture types (such as nonabsorbable silk and absorbable synthetics), sizes (thick to so fine [ophthalmic] that it requires a magnifying glass to see them), and needles (such as small curved, and straight), these two suture setups will suffice for most situations in which a layperson might wish to stitch a wound. Ideally, you would use 5/O and 6/O (smaller diameter) suture material on the face, but this is more difficult to manipulate and tie if you—re inexperienced.

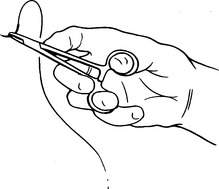

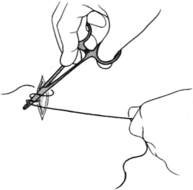

The instrument used to push the needle through the skin is a needle holder (Webster-style “needle driver”). It has finger handles like a scissors, and clamps open and shut with finger pressure to hold the needle firmly in its finely grooved jaws. It is held in a certain way to allow the wrist rotation that forces the curved needle through the skin.

The goal of stitching a wound is to bring the skin edges neatly together without excessive tightness, which would be manifested by a wound that is puckered up, and stitches that become buried. Most wounds swell a bit; thus, it is not necessary to cinch them closed with too much tension. After a wound is stitched, it should lie flat.

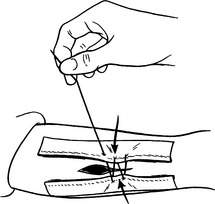

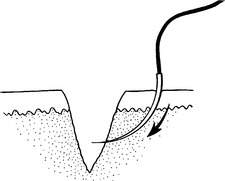

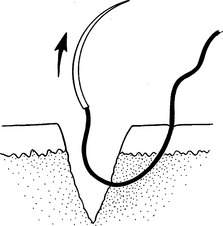

Wear sterile, nonlatex, nonpermeable surgical gloves if they are available, to avoid a reaction if you are allergic to latex. If you are not allergic to latex, latex gloves may be worn. If sterile gloves are not available, nonsterile gloves are acceptable. The needle should be placed into the jaws of the needle driver so that it can be clamped just behind (toward the suture) the midpoint of the curve (Figure 146). The needle should be oriented perpendicular to the skin and pushed through using a gentle rotating motion at the wrist; this pushes it out into the base of the wound (Figure 147). Then release the needle, reach down into the wound and regrip the needle that has exited into the wound, and pull the needle and suture through the wound until a 2 in (5 cm) tag is left outside the skin (Figure 148). The needle is once again grasped with the needle driver as before, pushed into the opposite side of the base of the wound at exactly the same depth as it entered into the wound on the other side (Figure 149), and rotated out through the external skin surface on the same side (Figure 150). Now you once again release the needle from the needle driver. The ideal suture placement is square or bottle shaped (Figure 151). As shown in this figure, the suture ideally crosses the wound close to its deepest point; slightly above (see Figures 148 to 151) or below (see Figure 151) is acceptable.

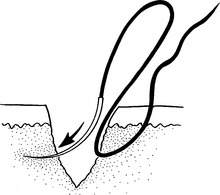

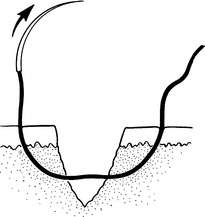

To tie a modified square knot, the long end (with the needle) of the suture is looped around the needle holder twice (Figure 152); then the short end of the suture—which was left as a 2 in (5 cm) tag—is grasped and lock-clamped tightly in the jaws of the needle driver (Figure 153). Holding the needle in one hand and the needle driver in the other, lay the double loop down flat against the skin to pull the wound together (Figure 154). To complete the knot, a single loop is thrown around the needle driver in the direction opposite the first (clockwise versus counterclockwise, or “over” versus “under”) (Figure 155), the short end of the suture once again grasped with the needle driver (Figure 156), and the knot pulled tight; cross your hands properly to lay the second loop-tie down flat (“square”) against the first (Figure 157). This process should be repeated three more times for a total of five “throws” to ensure that the knot won’t unravel. Cut the long ends ¼ in (0.6 cm) from the knot.

Place the stitches close enough together (approximately ¼ in [0.6 cm]) so that the wound is closed and there is no fat showing from underneath the skin. A nice way to close a wound is to place enough stitches to bring the wound edges into reasonable approximation and support the tension, and then close the remainder with cloth or paper adhesive strips. Put the first stitch at the midpoint of the wound, then at the midpoints of the remaining segments, and so forth. If you begin stitching at one end and work your way to the other, you run a much greater chance of misaligning the wound edges and ending up with a tear-shaped “dog-ear” that can’t be easily closed; this might force you to remove all of the stitches and begin all over again.

After you stitch a wound, it may ooze blood from the needle holes or the center of the wound. Apply firm, direct pressure with a gauze bandage or cloth for 10 to 15 minutes. To dress the wound, apply a thin layer of bacitracin or mupirocin ointment and an absorbent sterile bandage. Inspect the wound daily for signs of infection (see page 240). If an infection develops, remove a few stitches over the worst area to see if any pus is released. Allowing the wound to drain in one area may allow you to keep the other stitches in place for the normal duration of healing. When in doubt, however, take all of the stitches out and let the wound heal open or under loose approximation with adhesive strips.

Try to keep the wound dry for at least 4 days. Stitches are left in place for 14 days across the joints of the finger and hand, 10 days on the arms and legs, 7 days on the trunk and scalp, and 4 days on the face. After you remove a stitch, you can reinforce a wound with adhesive strips for a week to allow a margin of safety for healing.

If you are going to carry sutures with the intention of sewing a wound, you should have a physician teach you how to suture before you need to do it yourself. You can practice the technique on a pig’s foot, a chicken leg, or even a thick-skinned orange.

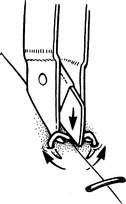

To remove a stitch from a healed wound, wash the wound carefully, and then cut the stitch on one side only of the visible knot. (If you cut on both sides of the knot, you may not be able to retrieve the buried portion of the stitch.) Grasp the knot with tweezers and pull the stitch out of the skin. If a crust has formed over the stitch, soften it up by applying moist compresses for 30 minutes before removing it.

STAPLING A WOUND CLOSED

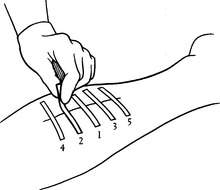

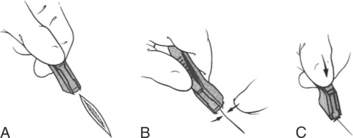

An excellent technique for closing relatively straight lacerations on the arm, leg, trunk, and scalp is stapling. A disposable surgical stapler, such as the Precise 5-, 15-, or 25-staple Disposable Skin Stapler (3M Medical-Surgical Division), allows precise placement of stainless-steel staples. The proper technique takes practice! Hold the skin edges together and press the business end of the stapler against the wound closure line, and then squeeze the stapler to discharge a staple into the skin (Figure 158). The recipient feels a quick pinprick. The closure is rapid and sturdy. The staples are left in place for 7 days on the scalp and trunk, and 10 days on the arm or leg. A disposable scissors-handle staple remover or smaller pinch-handle-style staple remover (Precise SR-1, 3M) is used to painlessly remove the staples (Figure 159).

If you are going to carry surgical staples with the intention of stapling a wound, you should receive proper instruction before the journey.

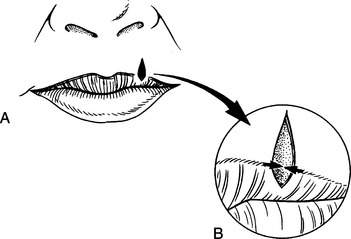

GLUING A WOUND CLOSED

Tissue adhesives (“glue”), which can be applied in a thin layer on top of a wound (not within the wound) to bond the edges together, have been recommended for superficial cuts. Two examples are 2-octyl-cyanoacrylate (DERMABOND) and n-2-butyl-cyanoacrylate (Histoacryl Blue or GluStitch). The “octyl” tissue glue products are thought to be more flexible than the “butyl” products when dry, but to carry less tensile strength, which is probably not significant for the intended uses. DERMABOND is available in a ProPen applicator that makes this product quite easy to apply. Tissue adhesive wound closure creates a closure that, while not initially absolutely as strong across a highly stressed area, like the skin overlying a finger joint, ultimately results in a similar cosmetic outcome to sewing the skin together. It cannot be used on the eye, inner moist surfaces of the mouth and lips, or areas with dense body hair. Routine tape-strip reinforcement is recommended, and topical ointments should be avoided, as they will weaken the bond between the glue and the skin. After the wound is closed with tissue adhesive, the victim may wash off or shower, but should not soak the wound, swim, or bathe in a tub, because prolonged moisture loosens the bond. Blot, rather than wipe, the area dry. Superglue should not be used to close full-thickness wounds, because it liberates heat when it contacts skin and causes an intense inflammatory reaction.

BANDAGING TECHNIQUES

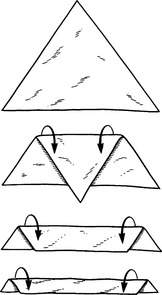

A triangular bandage is a three-cornered bandage, usually approximately 42 in (1 m) across the base. A cravat is a triangular bandage folded two or three times into a long strap (Figure 160).

The following tips should prove useful:

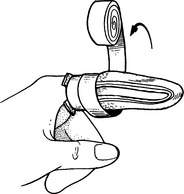

Finger bandage. Fold a 1 in (2.5 cm) rolled gauze back and forth over the tip of the finger to cover and cushion the wound (Figure 161). Then wrap the gauze around the finger until the bandage is snug and not overly bulky. On the last turn around the finger, pull the gauze over the top of the hand, so that it extends beyond the wrist. Split this tail lengthwise. Tie a knot at the wrist, and wrap the two ends around the wrist; tie again to secure the bandage. Another technique involves not splitting the tail, wrapping it around the wrist twice, and then bringing it up over the top of the hand around the base of the finger from the side opposite where it originated, looping it over the hand back to the wrist, and tying it off (Figure 162).

Hand bandage. The hand should be bandaged as if for a fracture, in the position of function (see Figure 39). Take care to place gauze or cotton padding between the fingers to separate and cushion them. Use a simple figure-of-eight wrap across the palm.

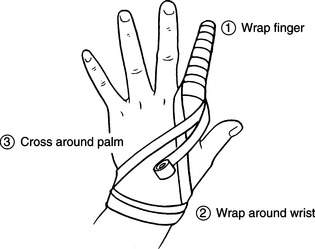

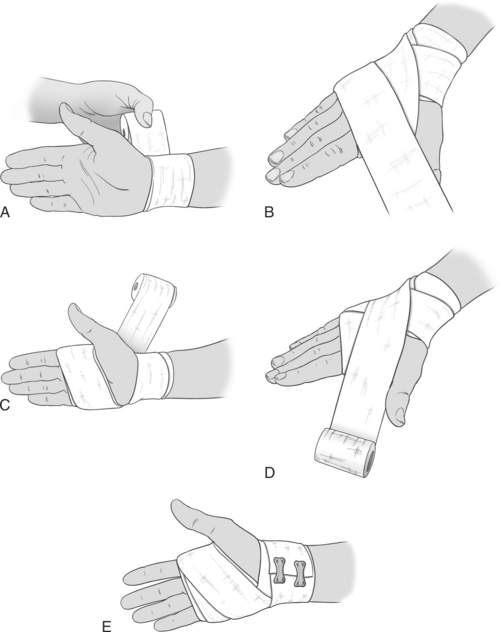

Wrist bandage. Begin by wrapping the wrist 2 to 3 times (Figure 163). Continue over the top of the hand, and then through the space between the thumb and fingers, across the palm. Repeat the process in a figure-of-eight pattern until the desired thickness and rigidity is obtained.

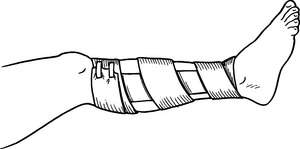

Arm or leg bandage. Cover the wound(s) with a gauze pad(s). Overwrap the wound using simple spiral turns of rolled gauze or a figure-of-eight pattern (Figure 164). Secure the bandage with adhesive tape in a spiral pattern to avoid a tourniquet effect. Whenever possible, don’t apply tape directly to the skin.

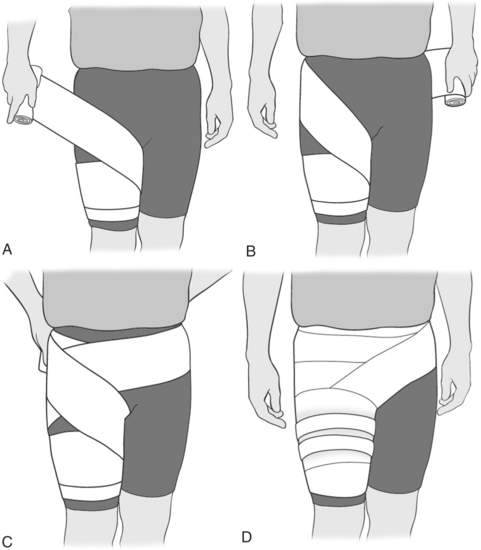

Thigh and groin bandage. Wrap a 6-inch elastic bandage around the mid-thigh in an inner to outer direction and continue up toward the pelvis (Figure 165). At the groin crease, continue up and around the waist one time. This anchors the bandage. Then proceed back down the thigh to complete the figure-of-eight pattern. If the injury is to the quadriceps (“quads”) or hamstrings (“hammies”) muscles, put additional wraps on the thigh. If the injury is to the groin, alternate wrapping around the hip with wrapping the thigh. Since this is a large bandage, a double-length wrap serves best.

Foot bandage. The foot should be bandaged as if wrapped for an ankle sprain, using gauze instead of elastic wraps (see page 288).

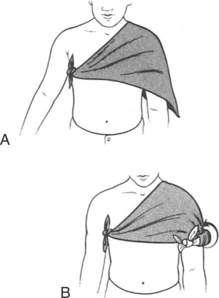

Shoulder bandage. To make a shoulder bandage (Figure 166) from a triangular bandage, lay the base over the shoulder at a downward diagonal across the chest (front and back) with the apex pointed down the arm. Roll or fold the apex back down a few turns to create the beginning of a cravat; tie this just in front of the opposite armpit. Roll or fold the apex up the arm in the same manner until the bandage achieves the desired coverage, and then tie off this smaller cravat segment with the knot visible on the outside of the arm.

Chest bandage. To wrap the chest with gauze, circle the chest and upper abdomen for a few turns. To keep the bandage from slipping toward the hips, bring it up over the shoulder every third or fourth turn. Secure with adhesive tape.

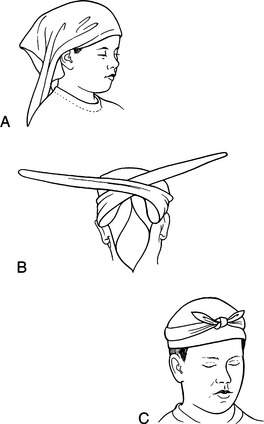

Head bandage. Place the base edge of a triangular bandage just over the eyes (Figure 167). Fold the base edge 1 in (2.5 cm) under to create a hem. Allow the bandage to fall back over the top of the head, with the apex point (tail) dropping over the back of the head. Then cross the other two free corners (at the ends of the hem) over the tail and tie them in a single turn (half of a knot). Continue to bring them around to the forehead and tie a complete square knot. Tuck the hanging tail over and into the half knot behind the head. If more pressure is necessary, tie a cravat directly over a gauze or cloth bandage.

Another way to secure a bandage to the side of the head, ear, or chin is to lay a cravat over the wound at the cravat’s midpoint, and then wrap it vertically over the head and under the chin (Figure 168). Cross the cravat on the side of the head at ear level, and wrap the ends in opposite directions horizontally so that one side loops across the forehead. Tie the knot behind the ear.

WOUND INFECTION

Despite your best efforts, a wound may become infected. The most common bacteria that cause wound infections are Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. The common signs of an infection include redness and swelling surrounding the wound, pus or cloudy discharge (pink, green, or cream colored), a foul odor (this is variable), fever, increased wound tenderness, red streaking that travels to the trunk from the wound, and swollen regional lymph nodes (see Figure 126).

If a wound is infected, its edges should be spread apart to allow the drainage of any pus. To do this, you need to remove some or all fastening bandages (such as butterfly bandages). The wound should then be irrigated copiously and dressed with a dry, absorbent, sterile bandage without bringing the wound edges tightly together. Begin to apply warm, moist compresses, using disinfected water, to the wound at least four times a day; also begin the victim on an antibiotic (dicloxacillin, cephalexin, or erythromycin). For a cat bite, use amoxicillin-clavulanate, cefuroxime axetil, azithromycin, clindamycin plus ciprofloxacin, or penicillin plus dicloxacillin. For a wound incurred in ocean, river, or lake water, administer ciprofloxacin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as an additional antibiotic.