CHAPTER 56 Minimally Invasive Posterior Approaches to the Spine

Surgical Anatomy of the Posterior Paraspinal Muscles

The posterior lumbar paraspinal muscles are responsible for maintaining spinal posture in its neutral position. Furthermore, the paraspinal muscles guard the spine from excessive bending that would otherwise endanger the integrity of the intervertebral discs, facet joints, and ligaments.1 It is the body’s dynamic stabilizing system that prevents pain and injury to spinal column due to the repetitive loads during the course of daily activities. The posterior paraspinal muscles are composed of several muscle groups that run along the thoracolumbar spine and attach caudally to the sacrum, sacroiliac joint, and iliac wing.

Posterior spine surgery using midline approaches inherently causes damage to surrounding muscles.2,3 Muscle injury leads to long-term muscle atrophy, which in turn leads to decreased force production capacity of the muscle.2,4–12 The multifidus muscle is most severely injured when using this approach for several reasons. First, its medial location inherently requires it be displaced most during retraction. This predisposes the muscle to greater retraction pressures and makes it more vulnerable to disruption of its neurovascular supply.2,7 Of equal importance, the midline posterior approach inevitably leads to disruption of the multifidus tendon attachment to the spinous process, as well as the integrity of the dorsolumbar fascia.

Key Concepts for Minimally Invasive Spine Retraction Systems

A key advancement in minimally invasive surgery came from Foley and colleagues13 with the development of the tubular retractor. A cylindrical retractor allows the surgical corridor to be opened via serial dilation using sequentially larger concentric tubes. This decreases the need for muscle stripping during the exposure. Furthermore, a tubular retractor maximizes the surface contact area, which in turn minimizes the pressure per unit area. Another key concept in MIS is use of a retractor holder mounted to the table instead of using a “self-retaining” mechanism. In a self-retaining retractor system, constant pressure on the tissues must be exerted to hold the retractor in place. Studies show that the maximum intermuscular pressure around a tubular retractor decreases by 50% within 3 seconds.14 Thereafter, the pressure is undetectable. With self-retaining retractors, the pressure remains unchanged.

Posterior Lumbar Approaches

Tubular Microdiscectomy

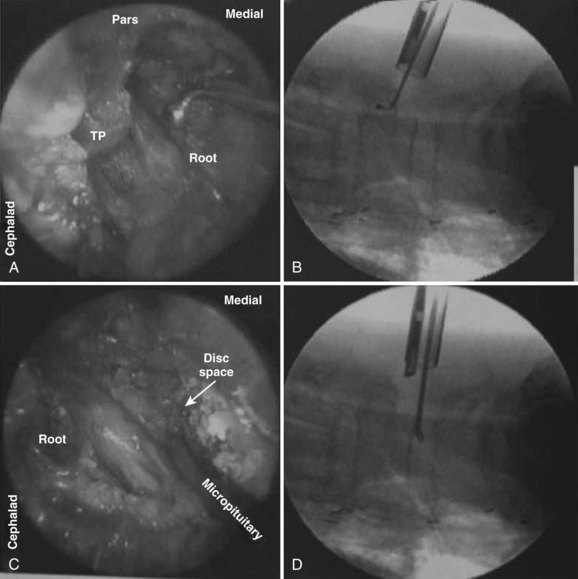

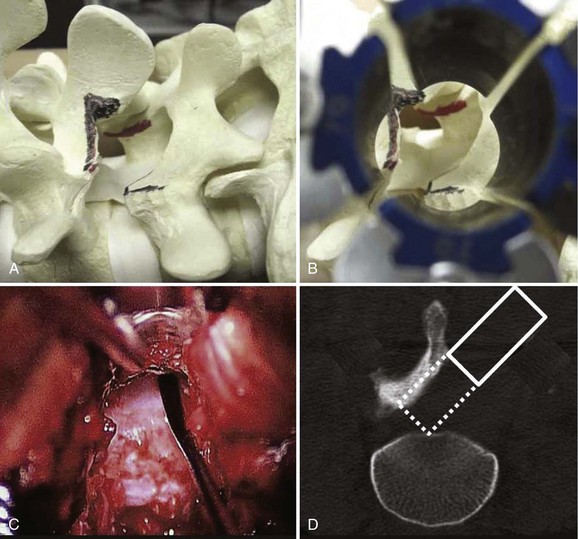

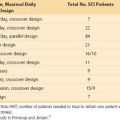

The treatment of herniated discs via MIS tubular microdiscectomy is the most common technique currently used in the United States. This system, developed by Foley and Smith, consists of a series of concentric dilators and thin-walled tubular retractors of variable length. The use of the tubular retractor, rather than blades, allows the retractor itself to be thin walled (0.9 mm). The tube circumferentially defines a surgical corridor through the erector spinae muscles. The appropriate depth of retractor prevents the muscle from intruding into the field of view. The retractor allows for the appropriately sized working channel to permit spinal decompression. The typical retractor size is 14 to 18 mm for microdiscectomy (Fig. 56–1). Surgery is typically performed using an operating microscope. Several randomized controlled trials have been performed to compare traditional open microdiscectomy with minimally invasive tubular microdiscectomy.15–17 These studies all show that tubular microdiscectomy is safe and efficacious compared with well-established traditional techniques. Clinically significant superiority was not shown, likely reflecting the difficulty is demonstrating differences between the two already successful procedures.

Lumbar Decompression

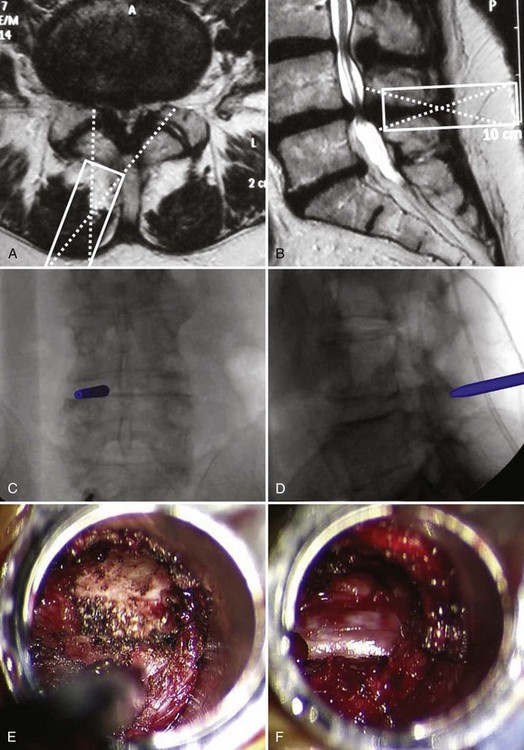

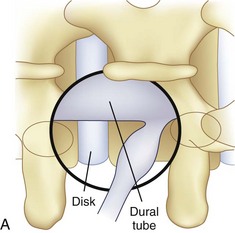

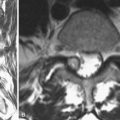

An important goal of minimally invasive posterior surgery is maintaining the tendinous attachment of the multifidus to the spinous process. During a traditional laminectomy, the spinous process is removed and the multifidus muscle is retracted laterally. Upon wound closure, the multifidus origin can no longer be repaired to the spinous process. The midline approach affords a symmetric view of the posterior elements, which allows for safe resection of the lamina, ligamentum flavum, and medial facets. The symmetric view allows the surgeon to readily identify and orient the surgical corridor. However, a thorough decompression can be achieved without need for removal of the spinous process. In a technique originally described by McCulloch and colleagues,18 the spinal canal can be approached through a unilateral portal via a hemilaminectomy technique. Decompression of the central canal and contralateral recess can be achieved by angling the tubular retractor dorsally to view the undersurface of the spinous process and contralateral lamina (Fig. 56–2). The dural tube can be gently pushed down, and the ligamentum flavum and contralateral superior articular process resected to achieve a bilateral decompression.

The efficacy and safety of minimally invasive posterior lumbar decompression have been assessed in multiple studies.18–24 In a review by Asgarzadie and Khoo,25 this technique provides long-term symptomatic relief equivalent to traditional open surgery but with significant reductions in operative blood loss, postoperative pain, hospital stay, and narcotic usage. The effect of the MIS learning curve remains a significant concern as increased complication rates are seen during the initial series of patients.26 Despite the learning curve, the overall complication rates remain low, even in patients who are elderly or medically frail.27–29

It is important to consider the anatomic variation of the lower lumbar spine with the upper lumbar spine with this particular technique. At L3 and above, the lamina between the spinous process and facet joint can be narrow (Fig. 56–3). With a unilateral approach, it may be difficult to reach the ipsilateral recess without excessively removing the ipsilateral inferior articular process. An option is to use a bilateral cross-over technique to reach the right lateral recess from a left-sided hemilaminectomy and vice versa. Anatomically, the lateral recess is more accessible through a contralateral approach when using the unilateral approach. In a preliminary study of four patients and seven levels of decompression, the total operating time was 32 minutes per level and the estimated blood loss was 75 mL. The average postoperative stay was 1.2 days. All patients had resolution of neurogenic claudication and there were no complications.30

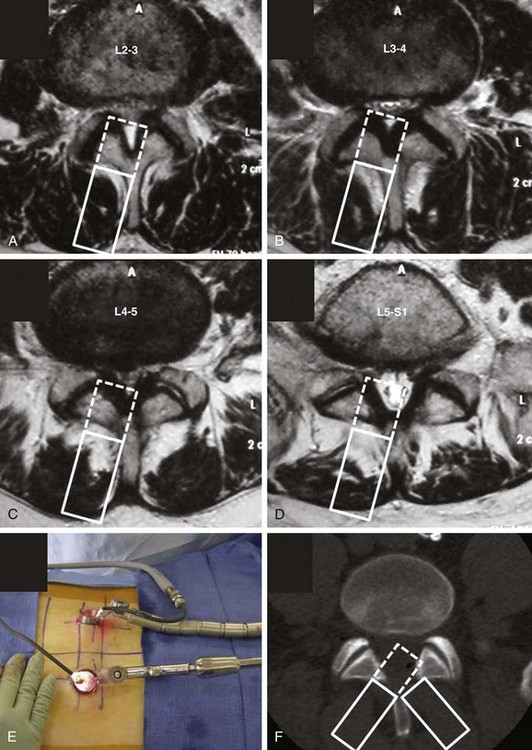

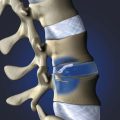

Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion

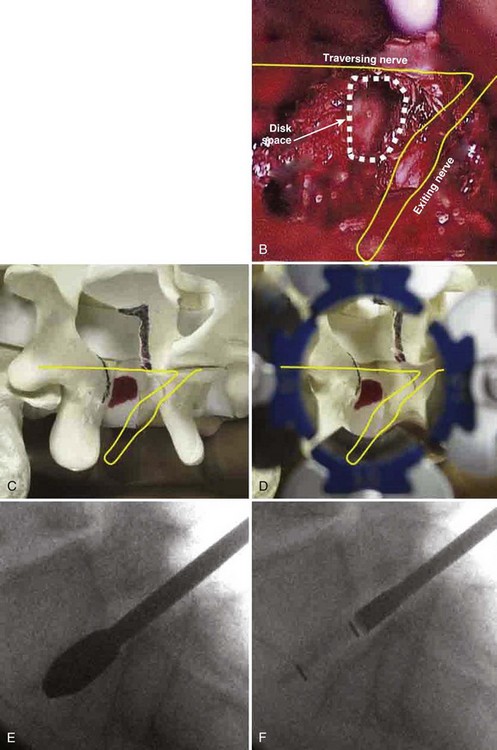

An extension of the minimally invasive hemilaminectomy technique is transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (MIS TLIF). The unilateral approach is used to perform the analogous decompression and is combined with a complete facetectomy. The surgical corridor is in the neurovascular plane between the multifidus and longissimus muscles (Fig. 56–4). A complete facetectomy allows for decompression of the spinal canal from the ipsilateral to the contralateral side (Fig. 56–5). Access to the disc space is through a window bordered medially by the dural tube, proximally by the exiting nerve root, and distally by the pedicle and superior endplate of the caudad vertebra, thus forming within the Kambin triangle (Fig. 56–6). Angled curettes are used to perform a subtotal discectomy from a unilateral approach. If necessary, an osteotome is used to remove the overhanging rim of the posterior vertebral endplate during discectomy. Fusion is performed using interbody spacers that can be placed anteriorly for maximum lordosis correction. A second cage may be inserted by using the smooth trials to push the first cages to the far side of the disc space. Dual cage constructs may be desirable when there is significant osteoporosis or at L5-S1 in a multilevel fusion.

The clinical safety and efficacy of this technique has been well established. Schwender and colleagues31 reported on 49 patients who underwent MIS TLIF through a paramedian, muscle-sparing approach using an expandable tubular retractor system. Of these patients, 26 patients had degenerative disc disease (DDD) with herniated nucleus pulposus (HNP), 22 had spondylolisthesis, and 1 had a Chance-type fracture as their primary diagnosis. The minimum follow-up was 18 months with a mean follow-up of 22.6 months. Operative time averaged 240 minutes (110 to 310 minutes), and average estimated blood loss (EBL) was 140 mL (50 to 450 mL). No patients required a blood transfusion, and there were no intraoperative complications. Length of hospital stay was 1.9 days on average (1 to 4 days). All 45 patients who had preoperative radicular symptoms had resolution of their symptoms. All patients with mechanical low back pain (LBP) had postoperative improvement of their pain. Four complications were noted postoperatively (two from malpositioned screws, one from graft dislodgement causing new radiculopathy, and the last from radiculopathy caused by contralateral neuroforaminal stenosis). Visual Analog Scale pain scores improved from 7.2 to 2.1, and Oswestry Disability Index scores improved from 46% to 14% at last follow-up.

Numerous studies have since confirmed the safety and efficacy of this technique.32–40 These studies show that MIS TLIF can achieve results comparable with traditional open techniques but with less postoperative pain, decreased blood loss, and shorter hospital stays, particularly when compared with anterior-posterior circumferential fusion.41

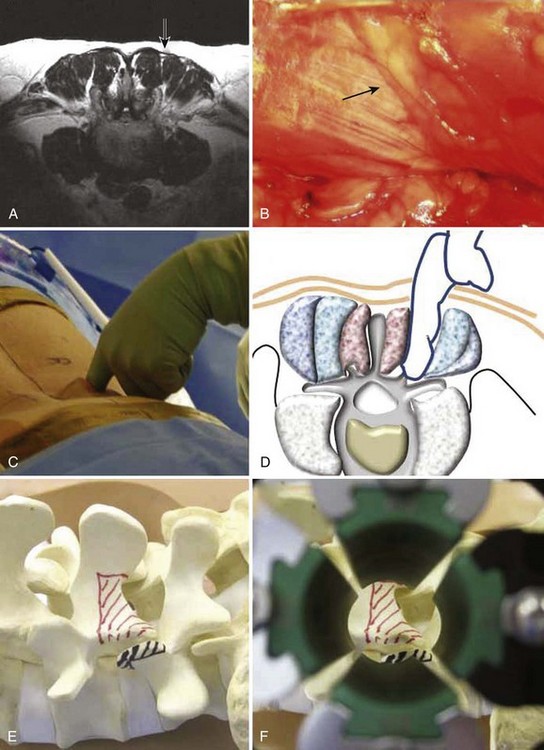

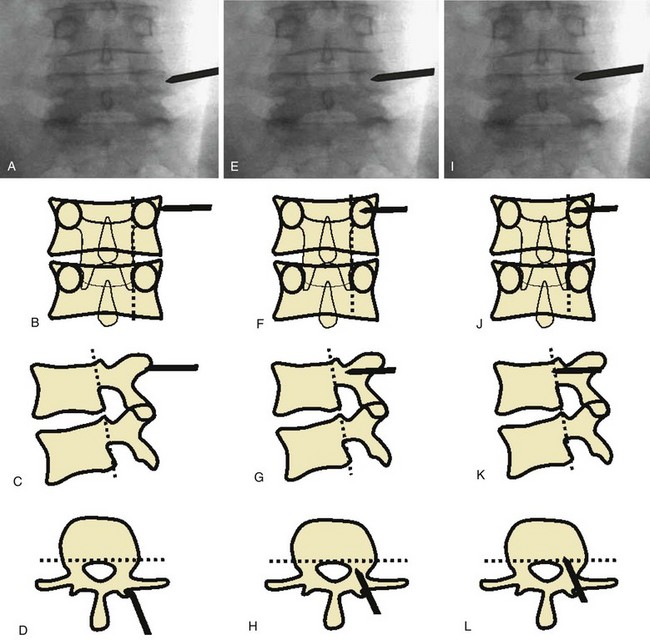

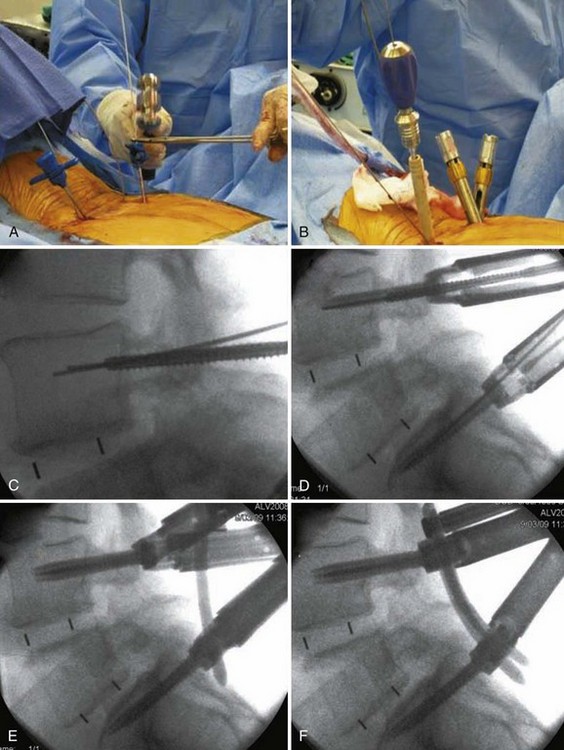

Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Instrumentation

Insertion of pedicle screws through a midline approach requires massive retraction of the multifidus muscle, subjecting the muscle to high retraction pressures and disruption of its osseo-tendinous attachments and neurovascular supply. The rationale for MIS pedicle screw insertion lies in the preservation of multifidus muscle function. Pedicle screw insertion can be performed percutaneously or via a paramedian mini-open technique. With the percutaneous technique, the pedicle is entered using a Jamshidi-type trocar needle under fluoroscopic control (Fig. 56–7). Once the needles are within the pedicle, the stylets are removed and guidewires inserted. The guidewire is then used to direct cannulated taps and screws into the pedicle (Fig. 56–8). Sequential soft-tissue dilators are used to create a path for the tap and screw. The outermost dilator can be used as a protective sleeve during pedicle tapping. A cannulated pedicle screw is then placed over the guidewire. Rods are inserted percutaneously to minimize soft tissue trauma.

The mini-open technique offers several advantages over the percutaneous method. It allows for direct visualization of the anatomy and the choice of using either cannulated or noncannulated pedicle screw systems. The mini-open technique also allows for greater access for bone grafting posteriorly. On the other hand, the mini-open technique threatens the medial branch of the dorsal rami, which extends downward to the transverse process of the caudal level, where it passes between the mammillary and accessory processes. It then curves posteriorly, where it branches to supply the multifidus muscle, the intertransverse muscles and ligaments, and the facet joint of the cephalad level. As a result, insertion of a pedicle screw through the mammillary process at one level can cause injury to the medial branch nerve of the dorsal rami (MBN) that supplies the adjacent cephalad level. In a cadaveric study comparing these MIS techniques, Regev and colleagues found that the mini-open technique causes injury to the medial branch of the dorsal rami more frequently than the percutaneous technique.42 They recommend that pedicle screw insertion at the cephalad level be performed percutaneously if one desires to minimize denervation of the multifidus complex at the cephalad adjacent level.

The overall safety and accuracy of minimally invasive pedicle screw insertion has been shown in several studies. Ringel and colleagues43 assessed a total of 488 pedicle screws implanted in 103 patients via a percutaneous technique. They found that only 3% of screws were rated as unacceptable, leading to nine screw revision surgeries. These results mirror a growing body of evidence that reflects the safety and efficacy of minimally invasive posterior spinal instrumentation.31,44,45 These results are comparable with pedicle screws inserted via a traditional open approach. In a meta-analysis of 130 studies and 37,337 pedicle screws placed, the overall screw accuracy was 91.3%.46

Limitations and Drawbacks

Radiation Exposure

Several techniques for minimally invasive posterior screw insertion exist, but the percutaneous pedicle screw technique is the least tissue disruptive and is currently adapted for single or multilevel fusions. Its use, however, depends on intraoperative fluoroscopy. In the past, fluoroscopy was mainly used for lateral fluoroscopic pedicle screw guidance in open surgery. However, multiplanar fluoroscopic techniques are necessary for minimally invasive spinal instrumentation. Obtaining multiple views in several planes increases accuracy but increases operating times. The operative time for two screws on the same vertebra level reaches 10 minutes or longer using advanced fluoroscopic techniques, whereas lateral-only fluoroscopic methods require less than 5 minutes per level.47–49 With increased insertion times associated with advanced fluoroscopic guidance, the cumulative exposure to radiation increased concomitantly.

Studies have shown that fluoroscopically guided pedicle screw placement exposes surgeons to 10 to 12 times the dose of radiation required when compared with nonspinal musculoskeletal procedures.50 Despite these concerns, the convenience of the C-arm, combined with a high degree of accuracy, has made intraoperative fluoroscopy an increasingly necessary part of advanced spinal surgery. The addition of navigation technology is a promising means of decreasing radiation exposure to the surgical team. Kim and colleagues51 showed that the use of navigation-assisted fluoroscopy for MIS TLIF markedly decreases direct exposure to radiation. In addition to reducing radiation exposure, navigation eliminates the need for cumbersome protective lead gear and clears the surgical field by removing the C-arm during surgery.

Learning Curve for Minimally Invasive Spinal Surgery

The barriers to widespread adoption of minimally invasive techniques appear to be related to technical difficulties of the procedures and a lack of adequate training opportunities. In a survey of spinal surgeons, Webb and colleagues52 showed that most surgeons perceive MIS to be efficacious and want to perform more MIS procedures. However, most have not pursued MIS surgery because of concerns with technical difficulties of the procedure and a lack of adequate training opportunities. The technical difficulty of the procedure, combined with inadequate training, is evident in initial studies of MIS surgery. Nowitzke evaluated the learning curve for tubular decompression and noted that 3 of the first 7 but none of the subsequent 28 cases required conversion to open.53 Villavicencio and colleagues41 noted a higher rate of overall perioperative complications, Dhall and colleagues54 found a higher rate of instrumentation complications, and Peng and colleagues55 noted longer operative times when comparing MIS TLIF versus open TLIF.

Summary

Pearls

Pitfalls

Key Points

1 Stevens KJ, Spenciner DB, Griffiths KL, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive and conventional open posterolateral lumbar fusion using magnetic resonance imaging and retraction pressure studies. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:77-86.

2 Foley KT, Gupta SK. Percutaneous pedicle screw fixation of the lumbar spine: preliminary clinical results. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:7-12.

3 Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(Suppl):S1-S6.

4 Peng CW, Yue WM, Poh SY, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes of minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1385-1389.

5 Dhall SS, Wang MY, Mummaneni PV. Clinical and radiographic comparison of mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in 42 patients with long-term follow-up. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:560-565.

1 Cholewicki J, Panjabi MM, Khachatryan A. Stabilizing function of trunk flexor-extensor muscles around a neutral spine posture. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22:2207-2212.

2 Gejo R, Kawaguchi Y, Kondoh T, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and histologic evidence of postoperative back muscle injury in rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:941-946.

3 Gille O, Jolivet E, Dousset V, et al. Erector spinae muscle changes on magnetic resonance imaging following lumbar surgery through a posterior approach. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:1236-1241.

4 Datta G, Gnanalingham KK, Peterson D, et al. Back pain and disability after lumbar laminectomy: is there a relationship to muscle retraction? Neurosurgery. 2004;54:1413-1420. discussion 20

5 Gejo R, Matsui H, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Serial changes in trunk muscle performance after posterior lumbar surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:1023-1028.

6 Hyun SJ, Kim YB, Kim YS, et al. Postoperative changes in paraspinal muscle volume: comparison between paramedian interfascial and midline approaches for lumbar fusion. J Korean Med Sci. 2007;22:646-651.

7 Kawaguchi Y, Matsui H, Gejo R, et al. Preventive measures of back muscle injury after posterior lumbar spine surgery in rats. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:2282-2287. discussion 8

8 Mayer TG, Vanharanta H, Gatchel RJ, et al. Comparison of CT scan muscle measurements and isokinetic trunk strength in postoperative patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1989;14:33-36.

9 Motosuneya T, Asazuma T, Tsuji T, et al. Postoperative change of the cross-sectional area of back musculature after 5 surgical procedures as assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:318-322.

10 Rantanen J, Hurme M, Falck B, et al. The lumbar multifidus muscle five years after surgery for a lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18:568-574.

11 Granata KP, Marras WS. An EMG-assisted model of loads on the lumbar spine during asymmetric trunk extensions. J Biomech. 1993;26:1429-1438.

12 Marras WS, Davis KG, et al. Trunk muscle activities during asymmetric twisting motions. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 1998;8:247-256.

13 Perez-Cruet MJ, Foley KT, Isaacs RE, et al. Microendoscopic lumbar discectomy: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:S129-S136.

14 Stevens KJ, Spenciner DB, Griffiths KL, et al. Comparison of minimally invasive and conventional open posterolateral lumbar fusion using magnetic resonance imaging and retraction pressure studies. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:77-86.

15 Arts MP, Brand R, van den Akker ME, et al. Tubular diskectomy vs conventional microdiskectomy for sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302:149-158.

16 Ryang YM, Oertel MF, Mayfrank L, et al. Standard open microdiscectomy versus minimal access trocar microdiscectomy: results of a prospective randomized study. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:174-181. discussion 81-82

17 Righesso O, Falavigna A, Avanzi O. Comparison of open discectomy with microendoscopic discectomy in lumbar disc herniations: results of a randomized controlled trial. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:545-549. discussion 9

18 Weiner BK, Walker M, Brower RS, et al. Microdecompression for lumbar spinal canal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24:2268-2272.

19 Palmer S, Turner R, Palmer R. Bilateral decompressive surgery in lumbar spinal stenosis associated with spondylolisthesis: unilateral approach and use of a microscope and tubular retractor system. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;13:E4.

20 Palmer S, Turner R, Palmer R. Bilateral decompression of lumbar spinal stenosis involving a unilateral approach with microscope and tubular retractor system. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:213-217.

21 Costa F, Sassi M, Cardia A, Ortolina A, et al. Degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis: analysis of results in a series of 374 patients treated with unilateral laminotomy for bilateral microdecompression. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007;7:579-586.

22 Iwatsuki K, Yoshimine T, Aoki M. Bilateral interlaminar fenestration and unroofing for the decompression of nerve roots by using a unilateral approach in lumbar canal stenosis. Surg Neurol. 2007;68:487-492. discussion 92

23 Khoo LT, Fessler RG. Microendoscopic decompressive laminotomy for the treatment of lumbar stenosis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:S146-S154.

24 Rahman M, Summers LE, Richter B, et al. Comparison of techniques for decompressive lumbar laminectomy: the minimally invasive versus the “classic” open approach. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51:100-105.

25 Asgarzadie F, Khoo LT. Minimally invasive operative management for lumbar spinal stenosis: overview of early and long-term outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38:387-399. abstract vi-vii

26 Ikuta K, Tono O, Tanaka T, et al. Surgical complications of microendoscopic procedures for lumbar spinal stenosis. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2007;50:145-149.

27 Podichetty VK, Spears J, Isaacs RE, et al. Complications associated with minimally invasive decompression for lumbar spinal stenosis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:161-166.

28 Rosen DS, O’Toole JE, Eichholz KM, et al. Minimally invasive lumbar spinal decompression in the elderly: outcomes of 50 patients aged 75 years and older. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:503-509. discussion 9-10

29 Sasaki M, Abekura M, Morris S, et al. Microscopic bilateral decompression through unilateral laminotomy for lumbar canal stenosis in patients undergoing hemodialysis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2006;5:494-499.

30 Regev G, Taylor W, Garfin SR, et al: The Use of Concurrent Bilateral Minimally Invasive Approach for Central and Neuroforaminal Spinal Decompression. Poster Presentation at 2008 Annual Meeting of the Society for Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery, San Diego, 2008.

31 Schwender JD, Holly LT, Rouben DP, et al. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF): technical feasibility and initial results. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2005;18(Suppl):S1-S6.

32 Anand N, Hamilton JF, Perri B, et al. Cantilever TLIF with structural allograft and RhBMP2 for correction and maintenance of segmental sagittal lordosis: long-term clinical, radiographic, and functional outcome. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31:E748-E753.

33 Deutsch H, Musacchio MJJr. Minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with unilateral pedicle screw fixation. Neurosurg Focus. 2006;20:E10.

34 Isaacs RE, Podichetty VK, Santiago P, et al. Minimally invasive microendoscopy-assisted transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with instrumentation. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:98-105.

35 Joseph V, Rampersaud YR. Heterotopic bone formation with the use of rhBMP2 in posterior minimal access interbody fusion: a CT analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:2885-2890.

36 Park Y, Ha JW. Comparison of one-level posterior lumbar interbody fusion performed with a minimally invasive approach or a traditional open approach. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:537-543.

37 Salerni AA. A minimally invasive approach for posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;13:e6.

38 Selznick LA, Shamji MF, Isaacs RE. Minimally invasive interbody fusion for revision lumbar surgery: technical feasibility and safety. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22:207-213.

39 Sethi A, Lee S, Vaidya R. Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion using unilateral pedicle screws and a translaminar screw. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:430-434.

40 Shen FH, Samartzis D, Khanna AJ, Anderson DG. Minimally invasive techniques for lumbar interbody fusions. Orthop Clin North Am. 2007;38:373-386. abstract vi

41 Villavicencio AT, Burneikiene S, Bulsara KR, et al. Perioperative complications in transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion versus anterior-posterior reconstruction for lumbar disc degeneration and instability. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2006;19:92-97.

42 Regev GJ, Lee YP, Taylor WR, et al. Nerve injury to the posterior rami medial branch during the insertion of pedicle screws: comparison of mini-open versus percutaneous pedicle screw insertion techniques. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1239-1242.

43 Ringel F, Stoffel M, Stuer C, et al. Minimally invasive transmuscular pedicle screw fixation of the thoracic and lumbar spine. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:ONS361-ONS366. discussion ONS6-7

44 Foley KT, Gupta SK. Percutaneous pedicle screw fixation of the lumbar spine: preliminary clinical results. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:7-12.

45 Eck JC, Hodges S, Humphreys SC. Minimally invasive lumbar spinal fusion. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15:321-329.

46 Kosmopoulos V, Schizas C. Pedicle screw placement accuracy: a meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32:E111-E1120.

47 Merloz P, Troccaz J, Vouaillat H, et al. Fluoroscopy-based navigation system in spine surgery. Proc Inst Mech Eng H. 2007;221:813-820.

48 Assaker R, Cinquin P, Cotten A, et al. Image-guided endoscopic spine surgery: Part I. A feasibility study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1705-1710.

49 Assaker R, Reyns N, Pertruzon B, et al. Image-guided endoscopic spine surgery: Part II: clinical applications. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26:1711-1718.

50 Rampersaud YR, Foley KT, Shen AC, et al. Radiation exposure to the spine surgeon during fluoroscopically assisted pedicle screw insertion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:2637-2645.

51 Kim CW, Lee YP, Taylor W, et al. Use of navigation-assisted fluoroscopy to decrease radiation exposure during minimally invasive spine surgery. Spine J. 2008;8:584-590.

52 Webb J, Gottschalk L, Lee YP, et al. Surgeon Perceptions of Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery. SAS Journal. 2008;2:62-66.

53 Nowitzke AM. Assessment of the learning curve for lumbar microendoscopic discectomy. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:755-762. discussion-62

54 Dhall SS, Wang MY, Mummaneni PV. Clinical and radiographic comparison of mini-open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion with open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion in 42 patients with long-term follow-up. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:560-565.

55 Peng CW, Yue WM, Poh SY, et al. Clinical and radiological outcomes of minimally invasive versus open transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34:1385-1389.