Chapter 35 Middle Cranial Fossa—Vestibular Neurectomy

With either the middle fossa or the posterior fossa approach, ablation of vestibular functions and vertigo is reported to be 85% to 99%,1–4 greatly exceeding the results of other treatment protocols. Technical difficulties have been cited by many authors as the major reason for abandoning the middle cranial fossa approach in favor of a predominantly neurosurgical approach from the posterior, especially as collaborative efforts between otoneurology and neurosurgery increase. Many centers in Europe and South America continue to use the middle fossa approach, however, with great success.3–6

The middle cranial fossa vestibular neurectomy performed at the University of Zurich is also known as the transtemporal-supralabyrinthine approach. In contrast to the middle fossa approach of House,7 which involves significant elevation of the middle fossa dura and retraction of the temporal lobe, the transtemporal-supralabyrinthine access to the internal auditory canal (IAC) is gained through bony reduction, with only minimal retraction of the dura.

PATIENT SELECTION

Unilateral peripheral vertigo without the full spectrum of Meniere’s disease may also benefit from vestibular neurectomy.8 In these patients, it is important to confirm the side of pathology with vestibular function tests if there is no hearing loss to provide a lateralizing sign. Other indications for vestibular neurectomy are rare. Labyrinthine trauma with residual hearing and disabling vertigo after successful stapedectomy with good hearing could be considered. Contraindications of surgery include an only hearing ear, signs of central vestibular dysfunction, and poor medical condition. Age older than 70 years is a relative contraindication subject to individual assessment.

SURGICAL SITE PREPARATION, POSITIONING, AND DRAPING

The surgical site is prepared in the operating room after the induction of anesthesia. Hair over the temporal region is shaved 9 cm above and 5 cm behind the pinna. The skin is washed with povidone-iodine (Betadine). The patient is secured on the Fisch operating table (Fig. 35-1) in supine position with the head turned to the side. Draping is standard except for a large-reservoir plastic bag, which is at the head of the table to catch excess irrigation fluid and blood.

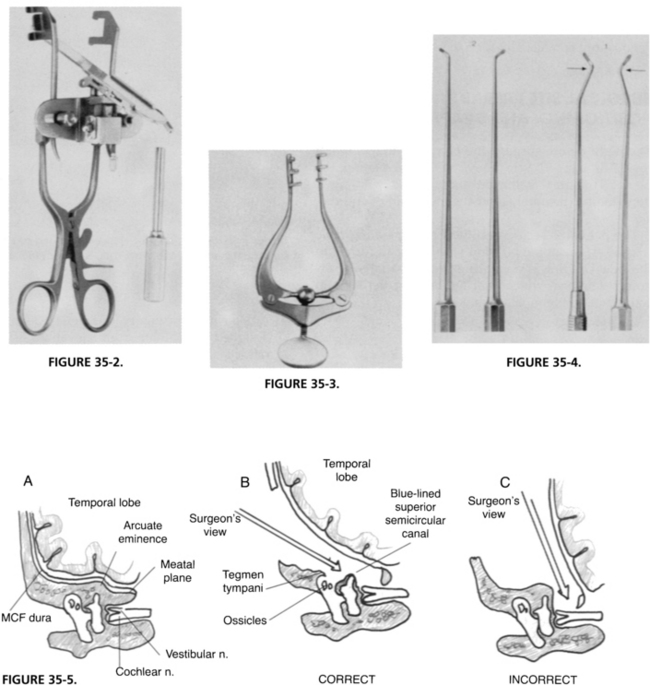

SPECIAL INSTRUMENTS

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

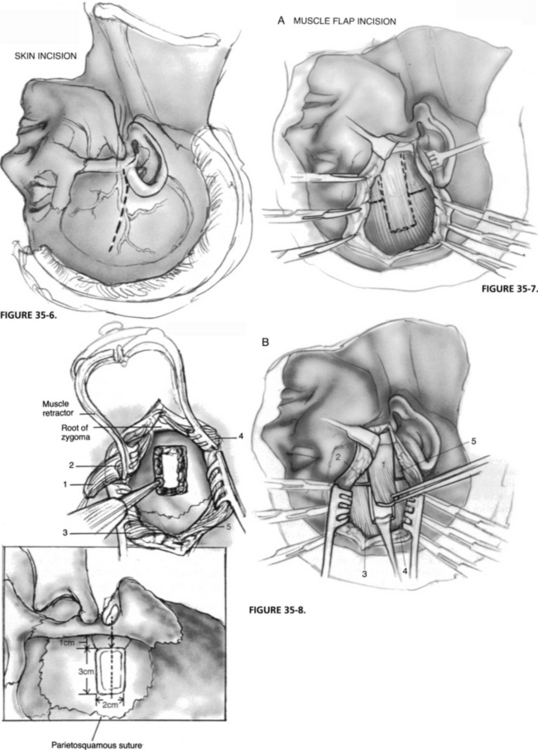

The objective of the transtemporal-supralabyrinthine approach for vestibular neurectomy is to gain access to the IAC through the exenteration of the supralabyrinthine bone, while dural elevation and retraction are limited to no more than 1.5 cm (Fig. 35-5).

Skin Incision

A preauricular incision is made from approximately the lower edge of the zygomatic root and extended to the temporal area at an angle for about 7 cm (Fig. 35-6). The depth of the incision is made to the temporalis fascia, and branches of the superficial temporal artery are divided and clamped. Retraction of the skin edges is provided by securing arterial clamps to the drapes.

Temporal Muscle Flap

After some undermining, the temporalis muscle is well exposed with a self-retaining retractor. Five muscle flaps (Fig. 35-7) are developed, elevated from the temporal squama, and retracted away with stay sutures. The temporal squama should be exposed from the root of the zygoma to the parietosquamous suture line. A temporalis muscle retractor should be used for the inferior exposure, where the identification of the zygomatic root is essential in the accurate positioning of the craniotomy.

Craniotomy

A 2 × 3 cm craniotomy (Fig. 35-8) is made perpendicular to, and at least 1 cm above, the temporal line, centered over the zygomatic root. This craniotomy is performed with a 5 mm cutting burr on a straight handpiece, and when dura is blue-lined, a 4 mm diamond burr is used. Care is taken to avoid injuring the dura and branches of the middle meningeal artery, which usually cross the undersurface of the bone flap in its midportion, but could be variable.

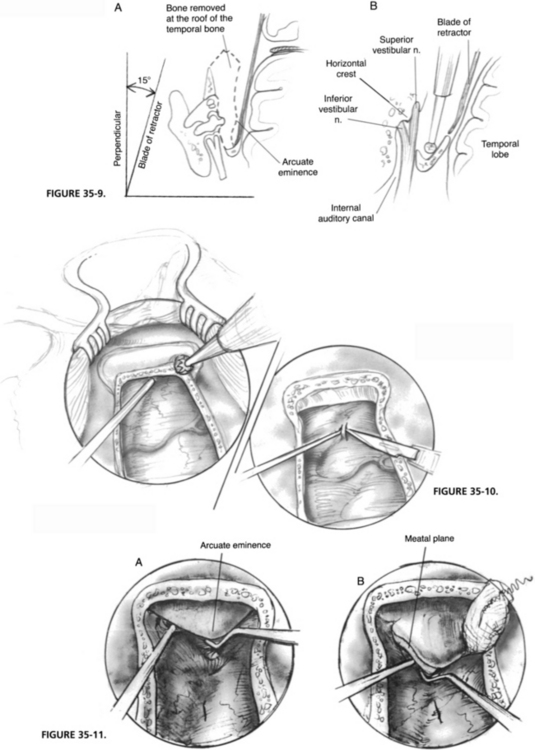

The bone flap is elevated from the dura with a dura raspatory and is kept in Ringer’s solution for later use. The dura is elevated from the edges of the craniotomy to facilitate the placement of the middle fossa retractor. In the region of the middle meningeal arterial branches, this step must be done with care. Sharp edges are removed with a small rongeur to prevent dural laceration. The craniotomy is extended inferiorly toward the zygomatic arch to the floor of the middle cranial fossa. Lateral extensions of 1 cm on each side provide better visibility for the next step (Fig. 35-9).

Dural Elevation

In addition to pharmacologic reduction of the intracranial pressure with mannitol and dexamethasone, cerebrospinal fluid decompression through a small dural incision facilitates dural elevation further; this should be done by first coagulating a small central portion of the dura and then elevating this area with a hook before making an incision (Fig. 35-10). With the use of a curved suction and angled microraspatory, dural elevation is performed from posteriorly forward. Vascular channels are coagulated and cut close to bone. Persistent bleeding from bone can be controlled by drilling over it with a diamond burr. Oozing from dural vessels at the corners can be controlled with oxidized cellulose (Oxycel) packed beneath a Cottonoid. The dural attachment to the petrosquamous suture is also coagulated and cut.

Exposure of the Meatal Plane and Arcuate Eminence

Dural elevation is extended to the superior petrosal sulcus and over the arcuate eminence. Moving anteriorly, the meatal plane is reached; this is an area bound by the arcuate eminence, superior petrosal sulcus, and facial hiatus (Fig. 35-11). When the meatal plane is not well defined because of a flat arcuate eminence, it can be identified after blue-lining the superior SCC. If the attachment of the greater superficial petrosal nerve limits the exposure of the meatal plane, it can be separated from dura gently to avoid traction injury of the facial nerve. Meticulous hemostasis in this region is important, and direct coagulation is avoided because of the proximity of the facial nerve.

Introduction of the Middle Cranial Fossa Retractor

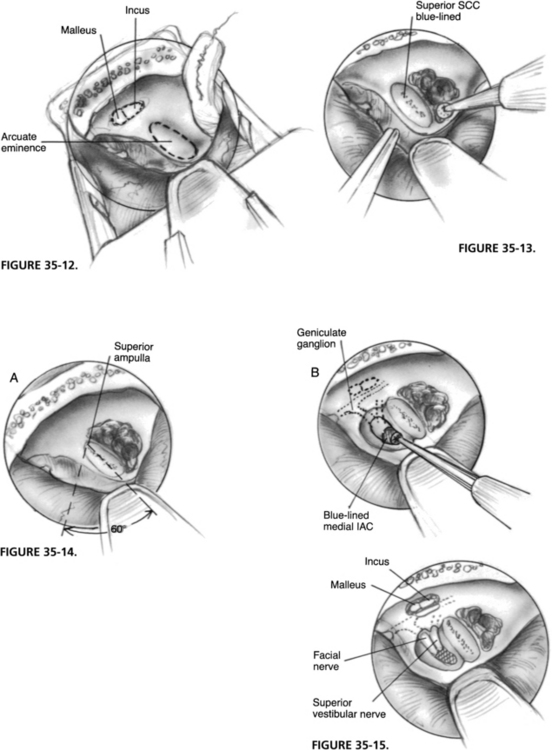

The middle cranial fossa retractor can be introduced at this point without the use of a microscope. The self-retaining jaws are firmly attached to the edges of the craniotomy first; the multidirectional stage is slid over the self-retaining portion and loosely placed. The dura is retracted with a suction to reveal the meatal plane to allow the accurate placement of the retractor blade, which is positioned parallel to the superior petrosal sulcus, its tip just beyond the arcuate eminence (Fig. 35-12). When the desired position is attained, screws on the multidirectional stage are tightened. Fine adjustments subsequently are done under the microscope.

Bony Exenteration and Blue Lining of the Superior Semicircular Canal

The operating table is now placed in Trendelenburg position to visualize better the area over the retractor blade. Bone posterior and lateral to the arcuate eminence is removed with a cutting burr (5 mm), enabling wider access for the final exposure and the progressive identification of the superior SCC. Because of the variable relationship of the superior SCC to the arcuate eminence, its identification is best accomplished from a posterolateral approach through the pneumatic cells; the yellow compact bone of the SCC can be readily exposed. To blue-line the SCC, removal of bone should be done with small diamond burrs (2.3 mm, 3.1 mm, 4.0 mm) in a wide rotatory fashion (Fig. 35-13).

Exposure of the Internal Auditory Canal

When the blue-line of the superior SCC is identified, using a 60-degree angle centered over the superior canal ampulla, the area of the meatal plane overlying the IAC can be defined. If the surgeon stays within this angle, there is no danger of damaging the facial nerve or the basal turn of the cochlea. The initial drilling is focused over the meatal plane, staying as close as possible to the blue-lined SCC. The axis of the drill is directed medioinferiorly, toward the superior lip of the porus and the medial roof of the IAC. These areas are progressively thinned out, until they are blue-lined (Fig. 35-14). The lateral exposure of the IAC involves the removal of bone over the meatal fundus and tegmen tympani (Fig. 35-15). This small triangular area is bordered by the ampulla of the superior SCC, and the facial nerve in its labyrinthine and tympanic portions; only 3 mm separates the superior ampulla from the genu of the facial nerve. The tegmen is opened if necessary to expose the malleus head and incus for better orientation. Bone over the meatal foramen and the distal superior vestibular nerve (SVN) is removed to identify the vertical crest (Bill’s bar), which gives the fundus its inverted-W shape. If this is not well defined, the SVN proximal to the ampulla should be exposed. The meatal foramen of the facial nerve should not be unroofed to avoid facial nerve injury.

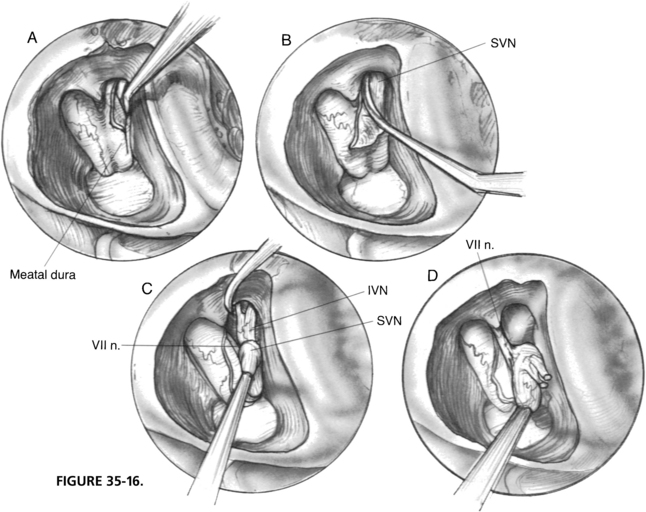

Vestibular Neurectomy

When the IAC is unroofed from the fundus to the porus, dura over the SVN is opened with a 1 mm hook. The nerve is identified and cut sharply with a neurectomy knife distal to the vestibular crest (Fig. 35-16). Avulsion of the SVN with a hook is discouraged because of the high incidence of deafness associated with this maneuver as a result of either traction or vascular injury to the cochlear nerve.

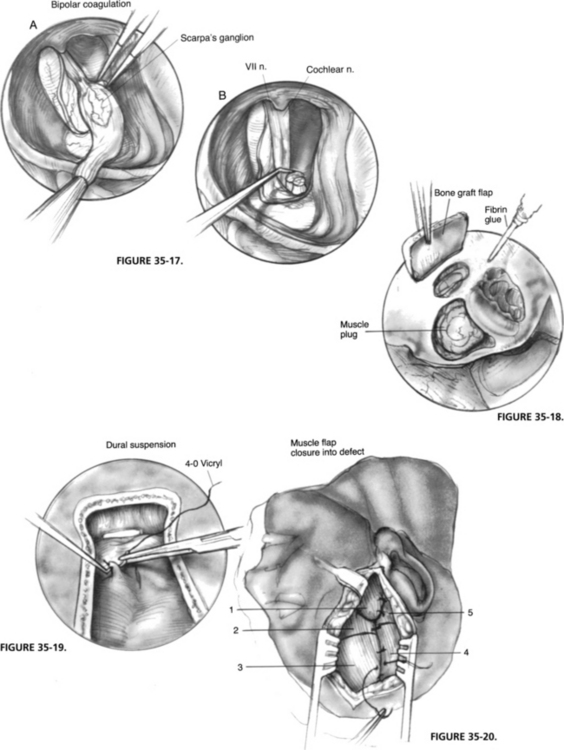

The meatal dura is incised along the posterior edge toward the porus. The cut end of the SVN is retracted with a microsuction to expose the saccular and singular branches of the inferior vestibular nerve, which are sectioned with a neurectomy knife. The entire vestibular nerve is stabilized with the suction while the vestibulofacial anastomoses are cut sharply with a neurectomy scissor. The vestibular nerve is now everted with Scarpa’s ganglion in full view, which is slightly darker and has a pronounced vascular pattern over it. The vessels are coagulated, and the nerve is resected proximal to the ganglion with neurectomy scissors (Fig. 35-17). The facial nerve should be exposed only partially, retaining most of its dural cover for protection. The cochlear nerve is hidden beneath the facial nerve and need not be exposed.

Repair of the Floor of the Middle Cranial Fossa

The IAC is covered with a free muscle plug and stabilized with fibrin glue. The tegmen defect is reconstructed with the thinner half of the craniotomy bone flap (wrapped in a gauze and fractured with a rongeur). This bony fragment usually straddles the tegmen defect perfectly, and is fixed in position with fibrin glue (Fig. 35-18). The middle fossa retractor is now removed.

Wound Closure

The dura is elevated with a dural hook and suspended to the adjacent temporalis muscle with 4-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) sutures (Fig. 35-19). This action obliterates the dead space between dura and bone, and prevents the formation of an epidural hematoma. The supralabyrinthine cavity is obliterated with the long, anteriorly based muscle flap (No. 1), which is sutured to its opposing flap (No. 5). The craniotomy bone flap is placed over the upper bony defect, and the remaining muscle flaps are sutured over it (Fig. 35-20). A single 3 mm suction drain is placed over the temporalis muscle and brought out through a separate stab incision posteriorly. The skin is closed in two layers with 2-0 catgut and 3-0 nylon sutures.

TIPS AND PITFALLS

RESULTS

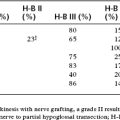

Follow-up of 3 to 15 years was available in 281 vestibular neurectomy patients operated on at the University of Zurich from 1967 to 1988.8 Of these, 218 of the operations were for Meniere’s disease, including four patients who underwent staged operations for bilateral disease, and 63 operations were for other forms of peripheral vestibular disorder. The success rate of transtemporal vestibular neurectomy to alleviate intractable vertigo was 98.2% for patients with Meniere’s disease, and 96.8% for patients with peripheral vestibular disorder.

In 61% of the patients with Meniere’s disease, evidence suggests a stabilizing effect of the surgery on residual hearing. An initial hearing improvement of more than 15 dB was seen in 12% of patients, with some improvement lasting 7 years, but invariably hearing deterioration ensued. Although difficult to explain, this hearing improvement could be due to (1) the division of cochlear efferents traveling with the vestibular nerve, (2) the reduction in the rate of endolymph production resulting from the devascularization and destruction of the dark cell areas, or (3) a change in the parasympathetic innervation of the inner ear subsequent to the sectioning of the olivocochlear bundle in the vestibulofacial anastomosis.9

ALTERNATIVE TECHNIQUES

The indication for endolymphatic sac surgery seems to be hearing preservation only in patients with early-stage disease. The long-term results at the University of Zurich have been as disappointing as the results reported by others.10–12 Endolymph-perilymph shunting procedures and peripheral labyrinthine ablation by either medical or surgical means continue to find support in many centers.13–17 Many procedures are of historical interest only, whereas others, such as intratympanic injection of vestibulotoxic medications, show some promise; however, the results in the control of vertigo and in prevention of hearing loss make them undesirable alternatives. Vestibular neurectomy and neurotomy (nerve section) seem to offer the best control of intractable vertigo refractory to medical therapy.

Retrolabyrinthine and retrosigmoid vestibular nerve sections1,2,11 have been proposed more recently as alternatives to the middle fossa (transtemporal-supralabyrinthine) vestibular neurectomy. It is, however, more logical to divide the vestibular nerve fibers in the distal IAC where fibers are distinct to achieve a complete section, while preserving the cochlear nerve. Also, the resection of the vestibular nerve, including Scarpa’s ganglion, ensures that regeneration does not occur. One is less likely to encounter large vessels in the distal portion of the IAC. These three important anatomic considerations are inadequately addressed with the posterior fossa approaches and must be kept in mind when comparing long-term results of the various surgical options.

Although the surgical access to the IAC in the transtemporal-supralabyrinthine approach is narrower compared with the access of the standard middle fossa approach, the dangers associated with temporal lobe retraction are practically eliminated. The posterior fossa approach entails more risks of severe cerebrospinal fluid leaks, meningitis, deafness, permanent facial paralysis, and intracranial hemorrhage, not to mention the common sequela of permanent headache2 that is often not emphasized. We concur that the transtemporal-supralabyrinthine approach is challenging and demands a thorough knowledge of the temporal bone; however, these challenges are similar to those of other neurotologic procedures.

1. House J.W., Hitselberger W.E., Mc Elveen J., et al. Retrolabyrinthine section of the vestibular nerve. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:212-215.

2. Silverstein H., Norrell H. Microsurgical posterior fossa vestibular neurectomy: An evolution in technique. Skull Base Surg. 1991;1:16-25.

3. Fisch U., Mattox D. Microsurgery of the Skull Base. New York: Thieme; 1988.

4. Garcia-Ibanez E., Garcia-Ibanez J.L. Middle fossa vestibular neurectomy: A report of 373 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88:486-490.

5. Castro D. Transtemporal-supralabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy for Ménière’s disease. In: Fisch U., Yasargil M.G., editors. Neurological Surgery of the Ear and Skull Base. Berkeley: Kugler & Ghedini Publications, 1989.

6. Portmann M., Sterkers J.M., Charachon R., Chouard C.H. Le Conduit Auditif Interne-Anatomie, Pathologie, Chirurgie. Paris: Librairie Arnette; 1973. 102-117

7. House W.F. Surgical exposure of the internal auditory canal and its contents through the middle cranial fossa. Laryngoscope. 1961;71:1363-1365.

8. Kronenberg J., Fisch U., Dillier N. Long-term evaluation of hearing after transtemporal supralabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. In: Nadol J.B., editor. The Second International Symposium on Ménière’s Disease. Amsterdam: Kugler & Ghedini Publications; 1989:481-488.

9. Chouard C.H. Acousticofacial anastomosis in Ménière’s disorder. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1975;101:296-300.

10. Bretlau P., Thomsen J., Tos M., Johnsen N.J. Placebo effect in surgery for Ménière’s disease: Nine-year follow-up. Am J Otol. 1989;10:259-261.

11. Glasscock M.E., Jackson C.G., Poe D.S., Johnson G.D. What I think of sac surgery. Am J Otol. 1989;10:230-233.

12. Brown J.S. A ten-year statistical follow-up of 245 consecutive cases of endolymphatic shunt and decompression with 328 consecutive cases of labyrinthectomy. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1419-1424.

13. Schuknecht H.F. Cochleosacculotomy for Ménière’s disease: Theory, technique, and results. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:853-854.

14. Pennington C.L., Stevens E.L., Griffin W.L. The use of ultrasound in the treatment of Ménière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1980;80:578-581.

15. Wolfson R.J. Labyrinthine cryosurgery for Ménière’s disease-present status. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:221-227.

16. Shea J. Perfusion of the inner ear with streptomycin. Am J Otol. 1989;10:150-155.

17. Moller C., Odkvist L.M., Thell J., et al. Vestibular and audiologic functions in gentamicin-treated Ménière’s disease. Am J Otol. 1989;9:383-391.