Chapter 11 Middle Childhood

Physical Development

Growth during the period averages 3-3.5 kg (7 lb) and 6-7 cm (2.5 in) per year (see Figs. 9-1 and 9-2 on the Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics website at www.expertconsult.com ![]() ). Growth occurs discontinuously, in 3-6 irregularly timed spurts each year, but varies both within and among individuals. The head grows only 2-3 cm in circumference throughout the entire period, reflecting a slowing of brain growth. Myelinization is complete by 7 yr of age. Body habitus is more erect than previously, with long legs compared with the torso.

). Growth occurs discontinuously, in 3-6 irregularly timed spurts each year, but varies both within and among individuals. The head grows only 2-3 cm in circumference throughout the entire period, reflecting a slowing of brain growth. Myelinization is complete by 7 yr of age. Body habitus is more erect than previously, with long legs compared with the torso.

Growth of the midface and lower face occurs gradually. Loss of deciduous (baby) teeth is a more dramatic sign of maturation, beginning around 6 yr of age. Replacement with adult teeth occurs at a rate of about 4 per year, so that by age 9 yr, children will have 8 permanent incisors and 4 permanent molars. Premolars erupt by 11-12 yr of age (Chapter 299). Lymphoid tissues hypertrophy, often giving rise to impressive tonsils and adenoids.

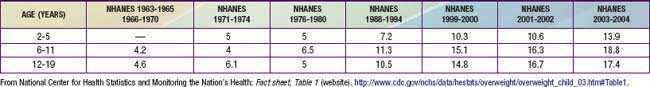

There has been a general decline in physical fitness among school-aged children. Sedentary habits at this age are associated with increased lifetime risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease (Chapter 44). The number of overweight children and the degree of overweight are both increasing; although the proportion of overweight children of all ages has increased over the last half century, this rate has increased over four-fold among children ages 6-11 yr (Table 11-1). Only 8% of middle and junior high schools require daily physical education class. One quarter of youth do not engage in any free-time physical activity, whereas the recommendation is for 1 hr of physical activity per day.

Table 11-1 PERCENT OVERWEIGHT INDIVIDUALS AMONG CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS AGES 2-19 YR, FOR SELECTED YR 1963-1965 THROUGH 1999-2002

Cognitive Development

School makes increasing cognitive demands on the child. Mastery of the elementary curriculum requires that a large number of perceptual, cognitive, and language processes work efficiently (Table 11-2), and children are expected to attend to many inputs at once. The first 2 to 3 yr of elementary school is devoted to acquiring the fundamentals: reading, writing, and basic mathematics skills. By 3rd grade, children need to be able to sustain attention through a 45 min period and the curriculum requires more complex tasks. The goal of reading a paragraph is no longer to decode the words, but to understand the content; the goal of writing is no longer spelling or penmanship, but composition. The volume of work increases along with the complexity.

Table 11-2 SELECTED PERCEPTUAL, COGNITIVE, AND LANGUAGE PROCESSES REQUIRED FOR ELEMENTARY SCHOOL SUCCESS

| PROCESS | DESCRIPTION | ASSOCIATED PROBLEMS |

|---|---|---|

| PERCEPTUAL | ||

| Visual analysis | Ability to break a complex figure into components and understand their spatial relationships | Persistent letter confusion (e.g., between b, d, and g); difficulty with basic reading and writing and limited “sight” vocabulary |

| Proprioception and motor control | Ability to obtain information about body position by feel and unconsciously program complex movements | Poor handwriting, requiring inordinate effort, often with overly tight pencil grasp; special difficulty with timed tasks |

| Phonologic processing | Ability to perceive differences between similar sounding words and to break down words into constituent sounds | Delayed receptive language skill; attention and behavior problems secondary to not understanding directions; delayed acquisition of letter-sound correlations (phonetics) |

| COGNITIVE | ||

| Long-term memory, both storage and recall | Ability to acquire skills that are “automatic” (i.e., accessible without conscious thought) | Delayed mastery of the alphabet (reading and writing letters); slow handwriting; inability to progress beyond basic mathematics |

| Selective attention | Ability to attend to important stimuli and ignore distractions | Difficulty following multistep instructions, completing assignments, and behaving well; problems with peer interaction |

| Sequencing | Ability to remember things in order; facility with time concepts | Difficulty organizing assignments, planning, spelling, and telling time |

| LANGUAGE | ||

| Receptive language | Ability to comprehend complex constructions, function words (e.g., if, when, only, except), nuances of speech, and extended blocks of language (e.g., paragraphs) | Difficulty following directions; wandering attention during lessons and stories; problems with reading comprehension; problems with peer relationships |

| Expressive language | Ability to recall required words effortlessly (word finding), control meanings by varying position and word endings, and construct meaningful paragraphs and stories | Difficulty expressing feelings and using words for self-defense, with resulting frustration and physical acting out; struggling during “circle time” and in language-based subjects (e.g., English) |

Implications for Parents and Pediatricians

As children are faced with more abstract concepts, academic and classroom behavior problems emerge and come to the pediatrician’s attention. Referrals may be made to the school for remediation or to community resources (medical or psychologic) when appropriate. The causes may be one or more of the following: deficits in perception (vision and hearing); specific learning disabilities; global cognitive delay (mental retardation); primary attention deficit; and attention deficits secondary to family dysfunction, depression, anxiety, or chronic illness (Chapters 14 and 29). Children whose learning style does not fit the classroom culture may have academic difficulties and need assessment before failure sets in. Simply having a child repeat a failed grade rarely has any beneficial effect and often seriously undercuts the child’s self-esteem. In addition to finding the problem areas, identifying each child’s strengths is important. Educational approaches that value a wide range of talents (“multiple intelligences”) beyond the traditional ones of reading, writing, and mathematics may allow more children to succeed.

Social, Emotional, and Moral Development

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Nutrition. Prevention of pediatric overweight and obesity. Pediatrics. 2003;112:424-430.

Boyce WT, Essex MJ, Woodward HR, et al. The confluence of mental, physical, social, and academic difficulties in middle childhood: I. Exploring the head waters of early life morbidities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:580-587.

Bradley RH, Houts R, Nader PR, et al. The relationship between body mass index and behavior in children. J Pediatr. 2008;153:629-634.

Dake JA, Price JH, Telljohann SK. The nature and extent of bullying at school. J Sch Health. 2003;73:173-180.

Datar A, Sturm R. Childhood overweight and elementary school outcomes. Int J Obes. 2006;30:1449-1460.

Davison KK, Markey CN, Birch LL. A longitudinal examination of patterns in girls’ weight concerns and body dissatisfaction from ages 5 to 9 years. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;33(3):320-332.

Elkind D. The hurried child: growing up too fast too soon, ed 3. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press; 2001.

Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA, et al. Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics. 2008;121(Suppl 3):S172-S191.

Hilbert A, Czaja J. Binge eating in primary school children: towards a definition of clinical significance. Int J Eat Disord. 2009;42:235-243.

Levine M. A mind at a time. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2002.

Rideout V, Roberts DF, Foehr UG. Generation M: media in the lives of 8–18 year-olds. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2005 (website) http://www.kff.org/entmedia/7250.cfm Accessed February 22, 2010

Rowley SJ, Burchinal MR, Roberts JE, et al. Racial identity, social context, and race-related social cognition in African Americans during middle childhood. Dev Psychol. 2008;44:1537-1546.

Strasburger VC. Media and children: what needs to happen now? JAMA. 2009;301:2265-2266.

United States Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention & Health Promotion. Physical activity guidelines for Americans: active children and adolescents (website). http://www.health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter3.aspx. Accessed February 22, 2010

Wells RD, Stein MT. Seven to ten years: the world of middle childhood. In: Dixon SD, Stein MT, editors. Encounters with children: pediatric behavior and development. St Louis: Mosby; 2000:402-425.

of these children have a television in their bedrooms. Parents should be advised to remove the television from their children’s rooms, limit viewing to 2 hr/day, and monitor what programs children watch. The Draw-a-Person (for ages 3-10 yr, with instructions to “draw a complete person”) and Kinetic Family Drawing (beginning at age 5 yr, with instructions to “draw a picture of everyone in your family doing something”) are useful office tools to assess a child’s functioning.

of these children have a television in their bedrooms. Parents should be advised to remove the television from their children’s rooms, limit viewing to 2 hr/day, and monitor what programs children watch. The Draw-a-Person (for ages 3-10 yr, with instructions to “draw a complete person”) and Kinetic Family Drawing (beginning at age 5 yr, with instructions to “draw a picture of everyone in your family doing something”) are useful office tools to assess a child’s functioning.