Chapter 68 Microdebrider-assisted tonsillectomy

1 INTRODUCTION

Tonsillectomy remains one of the most common surgical procedures performed on children. In contrast to several decades ago when infectious indications were common, the reason most children undergo tonsillectomy today is to relieve upper airway obstruction. Traditional ‘extracapsular’ tonsillectomy remains a fairly morbid procedure. Children routinely require several days off from school and parents are often forced to take time off from work. Despite advances in surgical technology a significant reduction in postoperative pain following this procedure has eluded surgeons. This is evidenced by the wide array of techniques available to the surgeon. Furthermore, the rate of postoperative hemorrhage has remained fairly stable despite the technique practiced. Partial ‘intracapsular’ tonsillectomy seeks to significantly reduce postoperative pain and hemorrhage risk while effectively treating upper airway obstruction.

2 PATIENT SELECTION

The safety of intracapsular tonsillectomy in the young patient has been studied. Bent et al. found no significant difference in the rate of readmission, pain, oral intake or anal-gesic requirements in patients younger than 3 years of age who underwent partial tonsillectomy compared to a control group.1

3 OUTLINE OF PROCEDURE

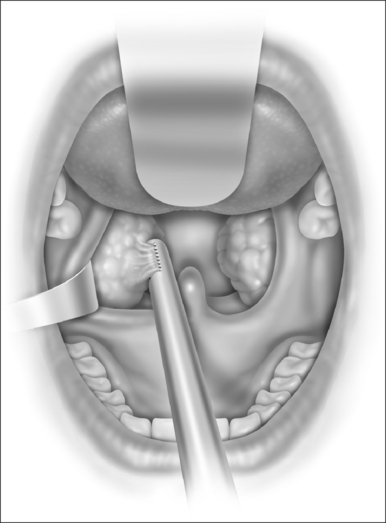

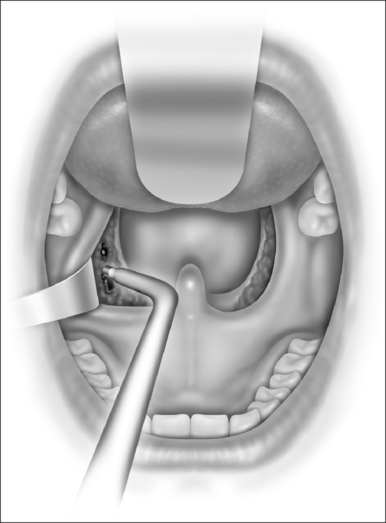

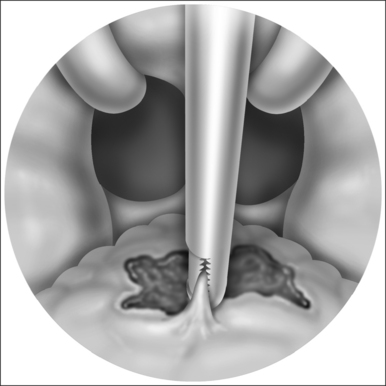

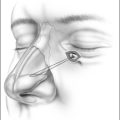

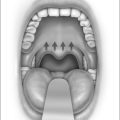

With the microdebrider set at a rate of 1500 rpm on oscillating mode, dissection of the tonsil begins at the inferior pole (Fig. 68.1). This helps prevent blood from obscuring visualization of the anterior and posterior pillars. Dissection proceeds from a lateral to medial direction until the plane of the pillars is reached. At this point it is generally helpful to further stabilize and control the anterior pillar to maximize tissue removal and minimize injury to mucosa. A Hurd elevator is particularly helpful in this circumstance as it can also help to medialize the remaining tonsil tissue, making dissection easier. Dissection is carried down to but not through the capsule of the tonsil. The use of a mirror can facilitate dissection of the superior pole. Care is taken to avoid inadvertent injury to the uvula, which can occur rapidly given the suction associated with the microdebrider. After dissection is completed, hemostasis is achieved using suction cautery with settings generally between 20 and 40 watts according to surgeon preference (Fig. 68.2). The contralateral tonsil is then dissected in an identical fashion. Once the procedure is completed the pharynx is irrigated with sterile normal saline and the mouth gag is allowed to relax. After approximately one minute the gag is reopened and hemostasis is confirmed. A suction catheter is then passed under direct vision and the stomach and hypopharynx are suctioned free of any blood or irrigation fluid that may cause post-extubation laryngospasm.The mouth gag and nasal catheters (if present) are removed and the patient is turned over to anesthesia personnel for extubation.

Studies have shown that, when compared to total tonsillectomy, intracapsular tonsillectomy may produce slightly increased intraoperative blood loss and require slightly more operative time. A recent study of 300 patients found that intracapsular tonsillectomy was performed on average in 10 minutes while electrocautery tonsillectomy took 8 minutes.2 This study also found no significant difference in overall blood loss but 15% of the intracapsular group lost more than 25 milliliters of blood compared to only 4% in the electrocautery group.

4 POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT AND COMPLICATIONS

In the recovery room patients are appropriately monitored. Oral diet is resumed, generally in the form of clear liquids, once an adequate level of consciousness is reached. Pain medicine may be administered either via an intravenous route or orally. The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the postoperative period is controversial and may lead to an increased risk of postoperative hemorrhage. It is our practice to use either acetaminophen or acetaminophen/narcotic combinations. The use of narcotic medication in the child with sleep apnea must be carefully considered. This population may have reduced respiratory drive in the presence of even low doses of narcotics. Patients who are observed in the hospital overnight should have continuous pulse oximetry. Consideration can also be given to temporary observation in an intensive care unit setting for patients with craniofacial abnormalities, severe preoperative sleep apnea, young age, history of bleeding disorder or other significant medical co-morbidities. It is our practice to routinely observe healthy patients less than 4 years of age overnight prior to discharge following tonsillectomy.

One potential advantage of intracapsular tonsillectomy is a potentially decreased risk of postoperative hemorrhage compared to traditional procedures. A recent multi-center retrospective review of 870 patients found a 0.7% rate of delayed postoperative hemorrhage.3

As mentioned earlier in this text, the risk of potential tonsil regrowth must be discussed with patients and their families preoperatively. A recent study reviewed 278 children who underwent intracapsular tonsillectomy.4 Nine patients (3.2%) experienced regrowth of tonsil tissue associated with snoring and two of these required revision surgery. We are currently in the process of reviewing a large series of patients who are several years removed from their intracapsular procedures to better understand the rate and severity of regrowth that does occur.

1. Bent JP, April MM, Ward RF, et al. Ambulatory powered intracapsular tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in children younger than 3 years. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:1197-1200.

2. Derkay CS, Darrow DH, Welch CW, et al. Post-tonsillectomy morbidity and quality of life in pediatric patients with obstructive tonsils and adenoid: microdebrider vs. electocautery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:114-120.

3. Solares CA, Koempel JA, Hirose K, et al. Safety and efficacy of powered intracapsular tonsillectomy in children: a multi-center retrospective case series. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;69:21-26.

4. Sorin A, Bent J, April M, et al. Complications of microdebrider-assisted powered intracapsular tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(2):297-300.

1. Sobol SE, Wetmore RF, Marsh RR. Postoperative recovery after microdebrider intracapsular or monopolar electrocautery tonsillectomy: a prospective, randomized, single-blinded study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(3):270-274.

3. Koltai PJ, Solares CA, Mascha EJ, et al. Intracapsular partial tonsillectomy for tonsillar hypertrophy in children. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(8 part 2) Suppl No. 100):17-19.

2. Koltai PJ, Solares CA, Koempel JA, et al. Intracapsular tonsillar reduction (partial tonsillectomy): reviving a historical procedure for obstructive sleep disordered breathing in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129(5):532-538.

4. Ray RM, Bower CM. Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea: the year in review. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;13(6):360-365.

5. Sobol SE, Wetmore RF, Marsh RR, et al. Postoperative recovery after microdebrider intracapsular or monopolar electrocautery tonsillectomy: a prospective, randomized, single-blinded study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(3):270-274.