Metastatic disease and palliative care

Introduction

Metastatic spread is defined as spread of breast cancer beyond the breast and ipsilateral axillary and/or internal mammary lymph nodes. With current therapies, metastatic disease is incurable and treatment is, by definition, palliative. Such patients may, however, benefit considerably from treatment. The principles and practice of treatment include a combination of active disease management, active symptom management, and appropriate support for patient and family. A more detailed review of the evidence is provided in the National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline.1

Presentation and prognosis

A minority of breast cancer patients (< 10%) present initially with metastatic disease.2 Most metastatic patients, however, present months or years after their primary treatment (surgery and appropriate adjuvant therapy). The natural history of breast cancer can be very long – patients still die from breast cancer 20 years and more after their initial treatment.3

Most patients present with symptoms of metastatic disease between follow-up visits;4 screening asymptomatic patients is not worthwhile.5,6 The common sites of metastatic spread are listed in Table 14.1; among other sites is the peritoneum, to which infiltrating lobular carcinoma, in particular, can spread and cause non-specific abdominal symptoms and/or obstruction.

Table 14.1

Symptoms commonly associated with metastatic spread to different organs

| Site | Common symptoms |

| Pleura | Dyspnoea (due to effusion) |

| Bone | Pain Pathological fracture Nausea and thirst (due to associated hypercalcaemia) |

| Lung | Dyspnoea Cough (dry cough is often seen with lymphangitis carcinomatosa) |

| Liver | Fatigue Nausea Anorexia Pain over liver |

| Brain | Headache (often worse first thing in the morning) Unilateral weakness Unsteady gait |

Staging

All patients presenting with locally advanced, inoperable or locally recurrent breast cancer should undergo a series of investigations to stage their disease adequately. In addition, patients presenting with metastatic disease at one site (e.g. bone) should have investigations to assess the extent of spread to other organs. The principal sites of spread are the thorax, bone and liver. Thus, tests to assess the extent of spread and organ function include a full blood count, clinical chemistry (urea and electrolytes, bone chemistry and liver function tests), tumour markers (carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 15-3, which can be useful to assess response7), bone scintigram and computed tomography (CT) scan of thorax abdomen and pelvis. Alternatives are a liver ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Increased long bone activity identified on bone scintigraphy should be further assessed by plain X-ray, supplemented by MRI if necessary, to assess degree of destruction and risk of pathological fracture. The brain should be assessed (CT or MRI) if the patient has symptoms suggestive of intracranial metastases. Urgent MRI of the whole spine is required if the patient has symptoms of spinal cord compression.

Clinicians need to understand the limitations of these investigations. Although bone scintigraphy is more sensitive than plain X-ray, it will not detect all bone metastases. If a patient has persistent bony symptoms and a negative bone scan (or negative in the symptomatic area) then an MRI should be requested, since it is more sensitive than bone scintigraphy. Discrete liver metastases are well visualised by most techniques, but diffuse infiltration may not be apparent on liver ultrasound. Positron emission tomography (PET)-CT cam be useful8 in resolving whether lymph nodes or isolated lesions seen in the lung or liver are indeed metastases (albeit infected or inflammatory conditions can also be positive on fluorodeoxyglucose PET).

Treatment

Systemic therapy

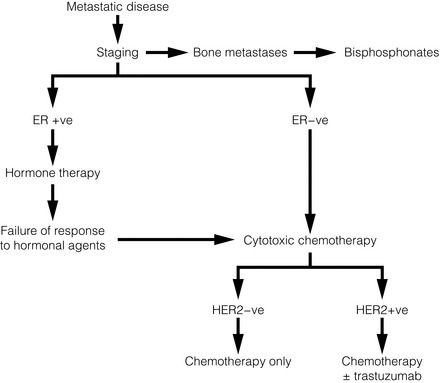

In general, a durable response to systemic therapy offers the best quality of life (see guidance in Fig. 14.1).

Figure 14.1 Outline of systemic therapy. Oestrogen receptor positive (ER + ve) includes all ER-positive and/or progesterone receptor-positive patients. ER-positive patients with lymphangitis carcinomatosa or liver metastases would normally be considered for chemotherapy in preference to hormone therapy.

Endocrine therapy

In 1896, Beatson10 demonstrated the endocrine sensitivity of breast cancer for the first time, by undertaking surgical oophorectomy for advanced breast cancer. Current therapy (Table 14.2) aims to either decrease levels of circulating oestrogen (ovarian ablation) or block its effect on the oestrogen receptor (anti-oestrogens). Ovarian ablation can be performed either by surgical removal (usually laparoscopically), by a short course of radiotherapy to the pelvis (infrequent – because of gastrointestinal side-effects), or the use of a luteinising hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH) agonist, e.g. goserelin. The latter is given by monthly injection into the anterior abdominal wall and is reversible; thus, if there is no tumour response, the patient’s periods can be restored and menopausal symptoms abolished. Tamoxifen is a partial oestrogen agonist but its effects on breast cancer cells are to antagonise oestrogen. It is effective in both pre- and postmenopausal women.

Table 14.2

Endocrine agents used in breast cancer

| Class of agent | Examples | Main side-effects |

| Ovarian ablation | Surgical oophorectomy Radiation menopause LH-RH agonists |

Menopausal symptoms |

| Anti-oestrogens | Tamoxifen Fulvestrant |

Menopausal symptoms Thrombo-embolism |

| Aromatase inhibitors | Anastrozole Letrozole Exemestane |

Menopausal symptoms Arthralgia Osteoporosis |

| Progestagens | Megesterol acetate | Weight gain Increased appetite Thrombo-embolism Glucocorticoid suppression |

Aromatase inhibitors (AIs; see next section) work in postmenopausal but not in premenopausal women. Particular caution should be taken with women who have chemotherapy-induced amenorrhoea, as they may still have some ovarian function, making AIs ineffective.12 In premenopausal women, a combination of LH-RH agonist plus AI has shown responses.13

Progestagens (e.g. megesterol acetate, medroxyprogesterone) at high dose have been used for many years, for their anti-oestrogenic action. Their main side-effects are significant weight gain and increased risk of thromboembolic disease. Suppression of glucocorticoid production has been reported,14 so patients may need hydrocortisone to cover physiological stress (e.g. pinning of pathological fractures, infections, etc.).

Postmenopausal patients

Ovarian ablation has no role. Oestrogen in postmenopausal women is produced by conversion of androstenedione to oestrone by aromatase,15 mostly in peripheral fat but also in liver, normal breast tissue and some breast cancers. Aromatase inhibitors (Table 14.2) reduce circulating oestrogen to nearly immeasurable levels.

There are two types of AI: non-steroidal (anastrozole and letrozole) and steroidal (exemestane). Their side-effects are, however, similar (Table 14.2), implying that these are due to their reduction of circulating oestrogen.

Fulvestrant is a pure oestrogen antagonist, as unlike tamoxifen it has no agonist action. It binds to, blocks and degrades the oestrogen receptor. Clinical trials in postmenopausal women have shown it to be as active as anastrozole.17 It is given monthly by intramuscular injection – a potential advantage where oral compliance is a problem. Studies with higher doses, 500 mg instead of the standard 250 mg dose, have shown that these higher doses appear effective.

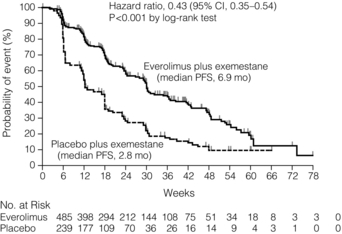

Adding biological agents such as mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin) inhibitors to endocrine agents such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors appears to increase response rate, duration of response and even overall survival (Fig. 14.2). Studies with these agents are continuing, although as yet they are not used outside clinical trials.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is used to treat ER-negative breast cancer, ER-positive breast cancer that is no longer sensitive to endocrine agents, and advanced ER-positive visceral disease. The main classes of drugs and their side-effects are listed in Table 14.3. These drugs are toxic and should only be prescribed by clinicians (usually oncologists) experienced in their use.

Table 14.3

Main cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs used in breast cancer

| Group of drugs | Examples | Main side-effects* |

| Anthracyclines | Doxorubicin Epirubicin |

Mouth ulcers Cardiomyopathy |

| Alkylating agents | Cyclophosphamide | |

| Antimetabolites | 5-Fluorouracil (capcitabine) Methotrexate |

Coronary spasm Hand–foot symdrome |

| Taxanes | Docetaxel Paclitaxel |

Peripheral and autonomic neuropathy Mouth ulcers |

| Vinca alkaloids | Vinorelbine | Peripheral neuropathy |

| Gemcitabine | ||

| Platinum | Carboplatinum Cis-platinum |

Neuropathy Renal failure |

*Nearly all these drugs can cause fatigue, nausea, vomiting, myelosuppression, cessation of periods (premenopausal women) and alopecia, so they are not listed individually.

The drug groups with the highest activity are the anthracyclines and the taxanes. The major limitation to anthracycline use is cardiomyopathy – the risk increasing as cumulative dose increases. A course of anthracyclines cannot, therefore, usually be repeated. Taxanes are active and more effective than some other regimens.19 Capecitabine is an oral prodrug of 5-fluorouracil. It is metabolised into the active component in the liver and possibly in the tumour itself.

As more agents are used in the adjuvant (or neoadjuvant) setting, the use of other active drugs such as vinorelbine, gemcitabine and platinum agents in metastatic disease is likely to increase. Platinum salts may have particular activity in the treatment of patients with basal-type tumours20 and are currently being studied in clinical trials.

Trastuzumab

A growth factor receptor gene, human epidermal growth factor (HER-2), is amplified in about 14% of breast cancers and is associated with a poorer prognosis.21 Trastuzumab is a humanised monoclonal antibody that targets the HER-2 receptor in patients whose tumours overexpress HER-2 as assessed by immunohistochemistry and/or fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) testing.

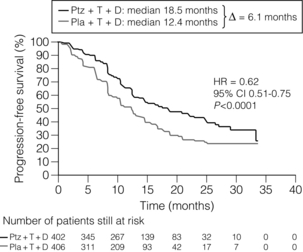

With these provisos, trastuzumab can be used in HER-2-positive patients. It is generally given with a course of taxane chemotherapy and continued as a single agent whilst response is maintained. Response may last months and even years. Trastuzumab is a large molecule and does not pass the blood–brain barrier, so patients who respond may develop brain metastases as the sole site of active disease. The brain metastases should be treated actively (see later), trastuzumab continued and the patient may regain remission. Other drugs targeting HER-2-positive breast cancers including pertuzumab and T-DM1 are in clinical trials. Combination of pertuzumab and trastuzumab looks particularly promising in patients with metastatic breast cancer (Fig. 14.3).

Figure 14.3 Progression free survival in the CLEOPATRA Trial of Docetaxel + Trastuzumab +/− Pertuzumab. Ptz = pertuzumab; T = trastuzumab; D = docetaxel; Pla = placebo. Reproduced from N Engl J Med 2012; 366(2): 109–19.

Lapatinib inhibits the tyrosine kinases of HER-2 and has been shown to be active in combination with capecitabine in patients who have relapsed on trastuzumab.23

Assessment of response

The most important method of assessing benefit is whether the patient’s symptoms have improved. Nevertheless, symptoms can improve independently of systemic therapy (e.g. analgesics for pain). Thus, it is also important to assess response to systemic therapy objectively. Locally recurrent disease can be assessed by regular photography and compared with previous clinical photographs. Similarly, monitoring measurable lesions on CT provides objective evidence of response. Assessment of bony metastases can be difficult. Plain X-ray changes are slow to develop with response, and responding sclerotic lesions will show little change. Bone scintigraphy can be misleading; 3 months after starting therapy, there may be increased uptake at sites of disease (‘flare’) indicating response and this can be indistinguishable from progression. Changes in the levels of tumour markers at 3 months can predict response24 or individual lesions can be monitored by MRI.1

Surgery

For patients presenting with metastatic disease it was formerly the case that surgery to the primary site was contraindicated because it will not help symptoms nor influence prognosis. This has now been questioned by a series of studies that have shown improved outcome in patients who have had surgery. Whether this improved outcome is due to selection bias or is genuine is not clear.25 Ongoing randomised trials will provide the answers. In those patients who are responding and have stable metastatic disease, surgery to control local disease in the breast and on the chest wall and in regional nodes should be considered.

Control of symptoms

Pain

Sixty-five per cent of patients with advanced cancer suffer pain.27 One-third of those with pain have one pain, another third have two different types of pain and the remaining third have three or more types of pain. Cancer-related nerve pain is common; 70–90% of pain responds to potent opioids if properly prescribed28 and the key to managing pain is careful assessment using a simple structured tool such as ‘NOPQRST’ (Box 14.1).

Analgesic requirements are likely to increase as illness advances.

Common concerns over opioid analgesics: Whilst morphine is the drug of first choice, side-effects or inadequate pain relief may limit benefit in 10–30% of patients. Switching opioids may reduce side-effects (Box 14.2) but if the pain is not opioid sensitive and toxicity is not a problem, switching from one to the other alone will not solve uncontrolled pain.30

Pain flares: Transient flares of severe pain are common and may be due to end of dose failure, a spontaneous worsening of pain or incident pain. The first two usually respond to an increased 24-hour dose of opioid.

Neuropathic pain: Patients often find it difficult to describe accurately nerve pain that typically has burning, shooting, stabbing, knife-like or tingling character and patients frequently accompany their description by rubbing the dermatome where the pain is felt. It has a distressing quality, which may not be adequately reflected in a simple 0–10 scale; hence a simple neuropathic pain screening tool has been recently developed.32 It is critical to recognise neuropathic pain, and to diagnose the underlying pathology, as it usually represents new and potentially treatable metastatic disease.

Neuropathic pain responds to opioids in approximately one-third of patients, but the remaining two-thirds may be difficult to manage. Nerve root involvement is most likely to result from brachial plexus involvement or epidural disease as a result of vertebral metastases and subsequent bony collapse. Drugs used primarily for reasons other than analgesia may help,33,34 such as low doses of antidepressants (amitriptyline or nortriptyline35), anticonvulsants (gabapentin, pregabalin36) or specific N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists (ketamine37). Methadone (specialist use only) is helpful when pain consists of a mixture of neuropathic and non-neuropathic pain, but there is insufficient published evidence on its use in cancer-induced pain.38 Finally, interventional procedures – cordotomy (unilateral nerve root pain) or epidural followed by an intrathecal implant – may be considered following consultation with the local pain or anaesthetic service.

Spinal cord compression: Patients with severe increasing back pain plus neuropathic pain referred around the chest wall, abdomen or down one or both legs should be assessed for the risk of spinal cord compression.

If spinal cord compression is suspected, then an urgent MRI scan of the whole spine should be organised. If the diagnosis is confirmed, radiotherapy or surgical intervention is indicated.40,41

Bony metastases: This is the commonest site of metastatic disease and can cause significant pain and morbidity.

Bisphosphonates: Bisphosphonates inhibit osteoclast activity, leading to decreased bone absorption.

The drugs used are most commonly the third-generation drugs zoledronate and ibandronate. Zoledronate is given intravenously every 4 weeks (or 3-weekly with chemotherapy); ibandronate can be given orally (on an empty stomach 1 hour before food). They are usually reasonably well tolerated but can cause flu-like symptoms, gastrointestinal disturbance and rarely osteonecrosis of the jaw.44 They should be given with caution in patients with renal impairment. Intravenous bisphosphonates can also reduce pain in patients with widespread bony metastases.45 A monoclonal antibody against rank ligand, denosumab, looks promising and is at least as effective as zoledronate and can be administered by subcutaneous injection.

Bone pain: Non-steroidal analgesics are helpful and are opioid sparing. The most common drug used by palliative medicine physicians is diclofenac (75 mg, slow release twice daily). A slow-release preparation reduces early morning pain due to overnight immobility. When pain is severe and distressing, immediate relief may need a non-oral prescription, e.g. 48-hour syringe driver with, for example, an opioid and a non-steroidal such as ketorolac, before returning to oral medication.

Fractures: Pathological fractures cause severe bony pain. Orthopaedic interventions can stabilise fractures of long bones (commonly femur or humerus). The results of orthopaedic interventions are usually better if done prophylactically rather than as an emergency. In either case, surgery will normally be followed by palliative radiotherapy. Most vertebral fractures are managed by palliative radiotherapy but selected cases may benefit from surgical stabilisation and/or decompression, especially where there is a risk of spinal cord compression.41

Effusions: Pleural spread is common, especially on the ipsilateral side. The patient usually presents with dyspnoea, and drainage with pleurodesis (using talc47) gives good symptomatic relief. Ascites is less common than pleural spread and is managed by repeated percutaneous drainage.

Cerebral metastases: This is typically a relatively late site of metastases. Occasionally, it may be the sole site of metastases. Presentation is usually with headache (characteristically worst in the morning if the patient has raised intracranial pressure), weakness and/or altered sensation, difficulty walking or severe persisting nausea. Diagnosis is confirmed by CT or MRI. A short course (five fractions) of palliative radiotherapy to the whole brain may provide useful palliation for patients whose clinical condition is reasonably well preserved. A patient who is in good general condition and has a single cerebral metastasis may get a more prolonged remission from neurosurgical removal followed by radiotherapy.

Nausea, vomiting and retching: These are common, distressing symptoms and are reported in 50–60% of patients suffering from advanced cancer. Numerous neurotransmitters and receptor types are involved; thus, anti-emetics are mainly neurotransmitter blockers (Table 14.4).48

Table 14.4

Management of nausea/vomiting due to cancer or its treatment

| Anti-emetic | |

| Metabolic, e.g. hypercalcaemia Drug/toxin induced, e.g. opioid |

Haloperidol 1.5 mg nocte/b.d. Levomepromazine 6 mg tab nocte |

| Haloperidol 1.5 mg nocte/b.d. Levomepromazine 6 mg nocte |

|

| Chemotherapy | Ondansetron Dexamethasone |

| Radiotherapy | Ondansetron |

| Raised intracranial pressure (cerebral metastases, brain stem or meningeal disease) | Cyclizine 50 mg t.d.s. or 150 mg/24 h s.c. Dexamethasone 4–16 mg in morning |

| Bowel obstruction (if surgery inappropriate) |

Cyclizine 50 mg p.o. t.d.s./150 mg/24 h s.c. Hyoscine butyl bromide 40–100 mg/24 h s.c. Octreotide 300–1000 mg/24 h s.c. Ondansetron 8–24 mg/24 h p.o., i.v., s.c. |

| Gastric stasis/outlet obstruction | Metochlopramide or domperidone 10–20 mg q.d.s. or Metochlopramide 30–100 mg/24 s.c. |

| Vestibular disease (base skull tumour) | Cyclizine 50 mg p.o. t.d.s. Levomepromazine 6 mg p.o. Haloperidol 1.5 mg b.d. Trial dexamethasone |

Constipation: Constipation is present in half of all patients with advanced cancer. It causes pain, distension, anorexia, nausea, malaise and embarrassment, and diagnostic confusion if it results in ‘overflow’ diarrhoea. Contributory factors include opioid use, reduced fluid and fibre intake, and reduced mobility. A recent Cochrane systematic review49 concluded that all laxatives assessed were ineffective for a significant proportion of patients, and some patients required multiple ‘rescue’ laxatives. Patients on opiates should be routinely prescribed a stimulant and a softener. Methylnaltrexone is a novel treatment for opioid-induced constipation.50

Overall care of the patient approaching death

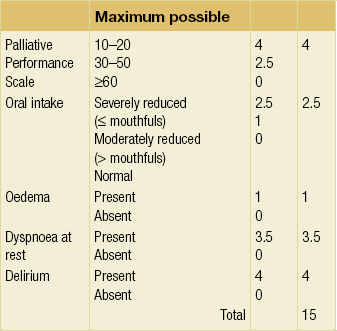

In advanced malignancy, symptoms rather than test results may be more useful in predicting survival. Patients with low performance status (Palliative or Karnofsky Performance Scales) have a poorer survival, although higher performance status does not necessarily predict for longer survival. Certain symptoms such as nausea, breathlessness and weakness have independent value as prognostic factors. Combining clinical prediction with other factors to produce a prognostic score (Table 14.5) gives simple and clinically more accurate useful bedside prognostic information.51

Recognition and communication that the patient may be dying

‘The physician does and does not want to pronounce a death sentence and the patient does and does not want to hear it’

Communication in difficult situations is difficult, and easy for professionals to avoid. Some patients prefer not to discuss these matters, as do some professionals. Both patients and professionals may collude to limit such discussions.52

There is usually more agreement about the most appropriate approach when a patient is actively dying, i.e. the last few days or hours, and the use of care pathways53 may be helpful in ensuring that all pre-emptive medications for distress, pain, etc. are prescribed and that the goals of care are clear to the patient, family and staff. Requests for transfer to hospice are common during this time, even when the patient is comfortable and their needs are being met. Other patients may wish to be at home and many specialist palliative care services can help with a swift, supported discharge.

References

1. National Institute of Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and treatment. Full Guideline. www.nice.org.uk, 2009.

2. Scottish Breast Cancer Focus Group and Scottish Cancer Therapy Network. Scottish Breast Cancer Audit 1987 and 1993: Report to the Chief Scientist and CRAG. Edinburgh: SCTN, ISD; 1996.

3. Brinkley, D., Haybittle, J.L., The curability of breast cancer. Lancet 1975; ii:95–97. 49738

4. Dewar, J.A., Kerr, G.R., Value of routine follow up of women treated for early carcinoma of the breast. Br Med J 1985; 291:1464–1467. 3933711

5. Givio Investigators, Impact of follow-up testing on survival and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1994; 271:1567–1592. 8182797

6. Rosselli Del Turci, M., Palli, D., Cariddi, A., et al, Intensive diagnostic follow-up after treatment of primary breast cancer: a randomized trial. National Research Council Project on Breast Cancer follow-up. JAMA 1994; 271:1593–1597. 7848404

7. Harris, L., Fritsche, H., Mennel, R., et al, American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumour markers in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5287–5312. 17954709

8. Brunetti, J.C. PET and PET-CT imaging of breast cancer. Appl Radiol. 2009; 38:9–16.

9. Wilcken, N., Hornbuckle, J., Ghersi, D., Chemotherapy alone versus endocrine therapy alone for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; 2 CD002747. 12804433

10. Beatson, G.T. On the treatment of inoperable cases of carcinoma of the mamma: suggestions for a new method of treatment, with illustrative cases. Lancet. 1896; ii:104–107. [162–5].

11. Robertson, J.F., Blamey, R., The use of gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists in early and advanced breast cancer in pre- and perimenopausal women. Eur J Cancer 2003; 7:861–869. 12706354

12. Smith, I.E., Dowsett, M., Yap, Y.S., et al, Adjuvant aromatase inhibitors for early breast cancer after chemotherapy induced amenorrhoea: caution and suggested guidelines. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:2444–2447. 16735701

13. Forward, D.P., Cheung, K.L., Jackson, L., et al, Clinical and endocrine data for goserelin plus anastrozole as second-line endocrine therapy for premenopausal advanced breast cancer. Br J Cancer 2005; 92:416–417. 15583687

14. Naing, K.K., Dewar, J.A., Leese, G.P., Megesterol acetate (Megace) therapy and secondary adrenal suppression. Cancer. 1999;86(6):1044–1049. 10491532

15. Miller, W.R., Aromatase inhibitors:mechanism of action and role in the treatment of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2003;30(4, Suppl. 14):3–11. 14513432

16. Gibson, L.J., Dawson, C.K., Lawrence, D.H., et al, Aromatase inhibitors for the treatment of advanced breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 1 CD003370. 17253488 This meta-analysis of all the trials comparing AIs with other endocrine therapies confirms the advantages of AIs.

17. Howell, A., Pippen, J., Elledge, R.M., et al, Fulvestrant versus anastrozole for the treatment of advanced breast cancer: a prospectively planned combined analysis of two multicentre trials. Cancer 2005; 104:236–239. 15937908

18. Carrick, S., Parker, S., Thornton, C.E., et al, Single agent versus combination chemotherapy for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009; 2 CD003372. 19370586 A systematic review of 43 trials and, although the results are summarised in the text, there is heterogeneity between the trials reflecting differences in efficacy of the drugs used.

19. Ghersi, D., Wilcken, N., Simes, J., et al, Taxane containing regimes for metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 2 CD003366. 15846659

20. Brody, L.C., Treating cancer by targeting a weakness. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:949–950. 16135843

21. Purdie, C.A., Baker, L., Ashfield, A., et al, Increased mortality in HER2 positive, oestrogen receptor positive invasive breast cancer: a population based study. Br J Cancer. 2010;102(4):719–726. 20104224

22. Slamon, D.J., Leyland-Jones, B., Shak, S., et al, Use of chemotherapy plus a monoclonal antibody against HER2 for metastatic breast cancer that overexpresses HER2. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:783–792. 11248153 The first randomised trial to demonstrate the activity of a monoclonal antibody in human breast cancer.

23. Geyer, C.E., Forster, J., Lindquist, D., et al, Lapatinib plus capecitabine for HER2-positive advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355:2733–2743. 17192538

24. Breast Speciality Group of the British Association of Surgical Oncology, Guidelines for the Management of Metatastic Bone Disease in Breast Cancer in the United Kingdom. Eur J Surg Oncol 1999; 25:3–23. 10188849

25. Rapiti, E., Verkooijen, H.M., Vlastos, G., et al, Complete excision of primary breast tumor improves survival of patients with metastatic breast cancer at diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:2743–2749. 16702580

26. Grossman, S.A., Sheidler, V.R., Swedeen, K., et al, Correlation of patient and caregiver ratings of cancer pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 1991; 6:53–57. 2007792

27. Van den Beuken, van Everdingen, M.H.J., de Rijke, J.M., et al, Prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: a systematic review of the past 40 years. Ann Oncol 2007; 18:1437–1449. 17355955

28. David, M.P., Glare, P., Quigley, C., et al. Opioids in cancer pain, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009.

29. King, S., Forbes, K., Hanks, G.W., et al, A systematic review of the use of opioid medication for those with moderate to severe cancer pain and renal impairment: a European Palliative Care Research Collaborative opioid guidelines project. Palliat Med 2011; 25:525–552. 21708859

30. Fine, P.G., Portnoy, R.K., Ad hoc expert panel on evidence review and guidelines for opioid rotation. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(3):418–425. 19735902

31. Dale, O., Moksnes, K., Kaasa, S., European Palliative Care Research Collaborative pain guidelines: opioid switching to improve analgesia or reduce side effects. A systematic review. Palliat Med 2011; 25:494–503. 21708856

32. Portenoy, R., Development and testing of a neuropathic pain screening questionnaire: ID Pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(8):1555–1565. 16870080

33. Attal, N., Cruccu, G., Baron, R., et al, EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17:1113–1123. 20402746

34. Bennett, M.I., Effectiveness of antiepileptic and antidepressant drugs when added to opioids for cancer pain: systematic review. Palliat Med 2011; 25:553–559. 20671006

35. Saarto, T., Wiffin, P.J., Antidepressants for neuropathic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 3 CD005454. Updated 2007. 16034979

36. Wiffen, P.J., McQuay, H.J., Edwards, J.E., et al, Gabapentin for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 3 CD005452. 16034978

37. Bell, R.F., Ecclestone, C., Kalso, E., Ketamine as an adjuvant to opioids for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003; 1 CD003351. Updated 2009. 12535471

38. Nicholson, A.B., Methadone for cancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 2 CD003971. Reviewed 2007. 17943808

39. Levack, P., Graham, J., Collie, D., et al, Don’t wait for a sensory level – listen to the symptoms: a prospective audit of the delays in the diagnosis of malignant spinal cord compression. Clin Oncol 2002; 14:472–480. 12512970

40. Loblaw, D.A., Perry, J., Chambers, A., et al, Systematic review of the diagnosis and management of malignant cord compression: the Cancer Care Ontario Practice Guidelines Initiative’s Neuro-Oncology Disease Site Group. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(9):2028–2037. 15774794

41. Metastatic spinal cord compression: diagnosis and management of adults at risk of and with metastatic spinal cord compression. NICE; 2008.

42. Pavlakis, N., Schmidt, R., Stockler, M. Bisphosphonates for breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2005. [CD003474].

43. Ross, J.R., Saunders, Y., Edmonds, P.M., et al, Systematic review of role of bisphosphonates on skeletal morbidity in metastatic cancer. Br Med J 2003; 327:469–472. 12946966 Both of these reviews (Refs 42 and 43) confirm from large randomised studies in women with advanced breast cancer that bisphosphonates when given in addition to systemic endocrine or chemotherapy reduce the risk of skeletal morbidity.

44. Marx, R.E., Sawatari, Y., Fortin, M., et al, Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone (osteonecrosis/osteopetrosis) of the jaws: risk factors, recognition, prevention and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005; 63:1567–1575. 16243172

45. Wong, R., Wiffen, P.J., Bisphosphonates for the relief of pain secondary to bone metastases (Cochrane review)The Cochrane Library. Chichester, UK: John Wiley, 2004. [Issue 2].

46. Chow, E., Harris, K., Fan, G., et al, Palliative radiotherapy trials for bone metastases: a systematic review. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(11):1423–1436. 17416863 A systematic review of 16 trials comparing single fractions vs. multiple fractions confirms that both are as effective in relieving pain, but patients who had a single fraction are more likely to be retreated.

47. Tan, C., Sedrakyan, A., Browne, J., et al, The evidence on the effectiveness of management for malignant pleural effusion: a systematic review. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006; 29:829–838. 16626967

48. Hallenbeck, J.L. Palliative care perspectives. Oxford University Press; 2003.

49. Miles, C.L., Fellowes, D., Goodman, M.L., et al, Laxatives for the management of constipation in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 4 CD003448. 17054172

50. Candy, B., Jones, L., Goodman, M.L., et al, Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; CD003448. 21249653

51. Lau, F., Cloutier-Fischer, D., Kuziemsky, C., et al, A systematic review of prognostic tools for estimating survival time in palliative care. J Palliat Care. 2007;23(2):93–112. 17853845

52. The, A.-M., Hak, T., Koeter, G., et al, Collusion in doctor–patient communication about imminent death: an ethnographic study. Br Med J 2000; 321:1376–1381. 11099281

53. National Care of the Dying – Audit of Hospitals (England). http://www.mcpcil.org.uk/files/hospital_pathway.pdf, December 2011