Chapter 31 Metastases to Abdominal-Pelvic Organs

Introduction

Metastasis is a complex process in which a tumor cell leaves the original site of disease, called the primary tumor, to spread to others parts of the body. Cancer cells can break away from a primary tumor, enter the blood vessels, circulate through the bloodstream, and be deposited in other organs of the body far from the primary tumor. When tumor cells metastasize to distant organs, the new tumor is called secondary or metastatic tumor.1

Epidemiology

Most tumors can metastasize. The most common sites of metastasis from solid tumors are the lungs, liver, and bones. However, the frequency, location, and patterns of metastases will depend on the primary tumor. Certain tumors rarely metastasize whereas some cancers tend to metastasize earlier than others.2 The presence of metastatic disease may also be correlated with the tumoral histology. Undifferentiated, anaplastic, and high-grade tumors have a tendency to give more metastases than well-differentiated and low-grade tumors.3 The cells in a metastatic tumor resemble those in the primary tumor. However, when the metastatic tumor is undifferentiated, the pathologist can use several adjuvant techniques, such as immunohistochemistry, to try to identify the origin of the primary tumor. In rare cases, patients will have metastatic disease without a primary tumor found, and these patients are considered to have a cancer of an unknown primary tumor.4

Patterns of Tumor Spread

The three principal pathways of tumor dissemination are hematogenic, lymphatic, and local invasion. The purpose of this chapter is to review hematogenous metastasis to intra-abdominal and pelvic organs. We divide our chapter by individual organ.

Key Points General principles

• Metastasis is a complex process in which tumor cells leave the original site to spread to other parts of the body.

• The most common sites of metastasis from solid tumors are the lungs, liver, and bones.

• The diagnosis of the presence of metastatic disease is one of the most important steps in staging patients.

• The three principal pathways of tumor dissemination are hematogeneous, lymphatic, and local invasion.

• Several imaging modalities may be used in the staging including US, CT, and MRI.

Key Points What the surgeon, radiation oncologist, and medical oncologist want to know

• The surgeon wants to know the presence of metastases, the number and size of the lesions, multifocality, and vascular involvement to plan resection.

• The radiation oncologist needs to know the location, size, and relationship of tumor to radiosensitive organs to plan radiation therapy field.

• The medical oncologist wants to know the number, location, and size of the lesions in the baseline study and the response to chemotherapy on follow-up imaging.

Liver

The most common solid organ to receive metastatic disease is the liver. Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who die of cancer have hepatic metastases at autopsy.5 The tumors that most commonly give metastases to the liver include lung; breast; gastrointestinal tract, such as esophageal, gastric, and colorectal; pancreas; and melanoma. Liver metastases usually appear as multiple solid lesions; however, in some cases, it may present as a solitary lesion, confluent masses, and infiltrative lesions that may mimic cirrhosis.6 Various imaging modalities may be used in the assessment of presence of hepatic metastases.

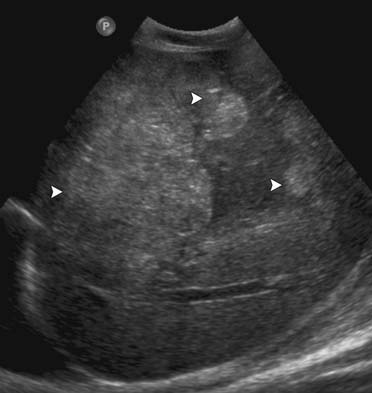

On US, liver metastases can have a variety of different appearances. Generally, the majority of the liver metastases present as multiple, solid, hypoechoic lesions from hypovascular tumors such as breast and lung cancer (Figure 31-1). They may show a peripheral hypoechoic rim known as the halo sign, which has been shown to represent a zone of proliferating tumor, a pseudocapsule, and/or compressed liver parenchyma.7 Other liver metastases may appear isoechoic, hyperechoic, and with an anechoic cystic component. Hyperechoic lesions are frequently associated with gastrointestinal primary tumors, renal cell carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma (Figure 31-2). Cystic metastases may demonstrate mural solid nodules or thick septations. Calcified metastases present with posterior acoustic shadowing and are usually seen with mucinous adenocarcinoma of the gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts.8

Although US has been widely used to detect liver metastases, its sensitivity in detecting liver metastases is lower than that of CT and MRI. Wernecke and coworkers9 reported a 53% sensitivity of US in the detection of hepatic masses. The application of new technologies such as microbubble intravenous contrast agents that improve the difference between the metastatic lesions and the background liver parenchyma increases the sensitivity of US in detecting hepatic metastases, even though its use is more common in some centers in Europe.10 Additional limitations of US include being operator-dependent, nonreproducible, and limited by abdominal gas.

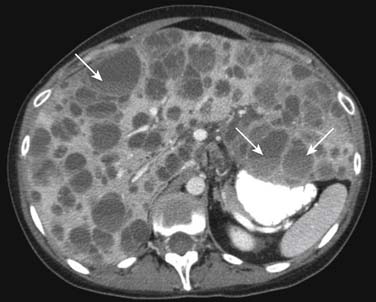

On unenhanced CT, the majority of the liver metastases appear as low-attenuating lesions compared with the surrounding liver parenchyma (Figure 31-3). Calcifications may be seen in the metastatic lesions from a primary mucin-secreting tumor of the gastrointestinal tract or ovary as well as after chemotherapy treatment (Figure 31-4). The use of intravenous contrast medium facilitates the distinction between focal lesions and the underlying liver parenchyma, improving the detection and characterization of hepatic lesions.11

On enhanced CT, the imaging features of liver metastases will depend on the primary tumor. The most common liver metastases are hypovascular compared with the adjacent liver and appear as low-attenuation lesions on the portal venous phase of imaging, when the surrounding normal liver is at its peak of enhancement (Figures 31-5 and 31-6). It may also present a hypoattenuating halo and areas of hemorrhage and necrosis when the growth exceeds the tumor neovascularity (Figures 31-7 to 31-9). Hypovascular metastases usually originate from primary tumors from the gastrointestinal tract including colon, rectum, esophagus, and stomach and other sites such as lung, pancreas, and prostate.12

Alternatively, the hepatic metastases with increased arterial flow relative to normal liver are best seen as hypervascular lesions during the arterial dominant phase of enhancement. Moreover, they may show washout and become hypoattenuating on delayed images (Figure 31-10). Hypervascular metastases usually originate from renal cell carcinomas and neuroendocrine tumors. Other primary tumors that may present with hypervascular liver metastases include medullary thyroid cancer, melanoma, and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.13

The reported accuracy of CT in detecting hepatic metastases ranges from 75% to 96% based on studies with patients with colorectal cancer.14,15 The limitations of CT include radiation exposure and the risk of adverse reaction with the use of iodine intravenous contrast agents.

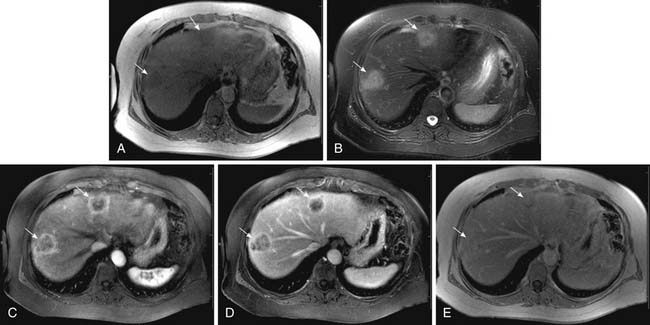

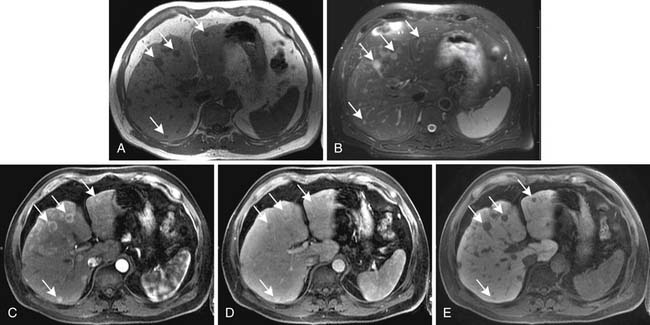

On MRI, hepatic metastases may have a variable appearance. The majority of liver metastases appear as low signal intensity on unenhanced T1-weighted images. Some tumors that may contain melanin or fat, such as metastases from melanoma and liposarcomas, respectively, can appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images. Hemorrhagic metastases may also appear hyperintense on T1-weighted images. On T2-weighted images, most liver metastases appear with high signal intensity (Figure 31-11). Lesions with central necrosis or cystic metastases can result in even higher signal intensity in T2-weighted images, whereas calcified lesions may be hypointense on T2-weighted images.16

After intravenous injection of gadolinium, most liver metastases show a peripheral ring of enhancement and are seen in the portal venous phase of imaging as hypointense lesions in comparison with the enhancing surrounding liver parenchyma (see Figure 31-11). Larger lesions may show cauliflower-like enhancement. The hypervascular metastases appear as foci of intense enhancement versus the background liver parenchyma during the arterial phase of enhancement (Figure 31-12). The presence of washout of the contrast from the lesion on delayed images is highly suspicious for malignancy.17 The reported sensitivity of MRI for the evaluation of suspected hepatic metastases ranges from 80% to 99%.18,19 The limitations of MRI include restriction to big centers and contraindication for patients with pacemakers and ferromagnetic implants.

Key Points Liver

• The liver is the most common solid organ to receive metastatic disease.

• Approximately 50% to 60% of patients who die of cancer have hepatic metastases at autopsy.

• Liver metastases may have a variable appearance and imaging features depend on the primary tumor.

• Most common liver metastases are hypovascular and appear as low-attenuation lesions compared with the adjacent liver parenchyma in the portal venous phase.

• Some hepatic metastases are hypervascular, presenting with increased arterial flow relative to normal liver, and are best seen during the arterial phase of enhancement.

Spleen

The spleen is an infrequent site of tumor metastases; metastases usually occur in late stages of cancer as a manifestation of widely disseminated disease. The incidence of neoplastic involvement of the spleen ranges from 0.3% to 16% depending on the type of primary tumor and the extent of disease on autopsy studies.20 The lack of afferent lymphatic vessels, the presence of a sharp angle at the origin of the splenic artery, the contractile nature of the spleen, and the inhibitory effect of the splenic reticuloendothelial system are some of the several theories that have been proposed to explain the relative paucity of splenic metastases.21

The most common primary sources of splenic metastases are breast, lung, ovarian, melanoma, colorectal, and gastric cancer. In cases of isolated splenic metastasis, ovarian and colorectal carcinomas are the most common causes. Most metastases to the spleen occur by hematogenous involvement resulting in parenchymal disease. The presence of surface/capsular lesions is often associated with peritoneal dissemination usually from ovarian cancer whereas direct splenic invasion is more commonly observed in gastric cancer and left renal cell carcinoma.22

Patients with splenic metastases are usually asymptomatic and the diagnosis is generally made by routine imaging studies. Eventually, patients may present with abdominal pain, splenomegaly, or a palpable mass. In rare cases, it may present as spontaneous rupture of the spleen.23

Parenchymal splenic metastases usually appear as multiple round solid hypoechoic lesions on US. In some cases, it may be a hypoechoic solitary lesion. Splenic surface involvement also appears hypoechoic on US.24

On CT scans, splenic metastases are typically solid round areas of slightly decreased attenuation in relation to the normal splenic parenchyma (Figure 31-13). Capsular metastases result in indentation of the splenic surface. Melanoma and ovarian cancers may also cause cystic splenic metastases, and ovarian metastatic lesions may calcify (Figures 31-14 and 31-15).24

On MRI, splenic metastases typically appear as hypointense to isointense lesions on T1-weighted images and as hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images. The metastases usually enhance after intravenous injection of contrast.25

Key Points Spleen

• The incidence of neoplastic involvement of the spleen ranges from 0.3% to 16% depending on the type of primary tumor and the extent of disease on autopsy studies

• Most common primary sources of splenic metastases are breast, lung, ovarian, melanoma, colorectal, and gastric cancer.

• Metastases to the spleen may be parenchymal disease, surface/capsular lesions, and direct invasion.

Gallbladder

Metastases to the gallbladder are rare in clinical practice. Although infrequent, there are some reports in the literature of metastases to the gallbladder from some primary cancer such as melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, lung, breast, and stomach.26 Among these, malignant melanoma is reported to be the most common origin of gallbladder metastases, accounting for 50% to 60% of cases of gallbladder metastases. According to Shimkin and colleagues,27 malignant melanoma can metastasize to the gallbladder in 4% to 20% of cases.

Gallbladder metastases generally do not cause clinical symptoms and are usually an incidental postmortal finding. However, in rare symptomatic cases, the most frequent presentation is acute cholecystitis. Nassenstein and Kissler28 reported a case of a 45-year-old man who developed symptoms of an acute cholecystitis caused by a metastasis from a non–small cell lung cancer to the wall of the gallbladder.

The most used modality in the assessment of both primary and metastatic lesions of the gallbladder is US. US can demonstrate focal thickening of the gallbladder wall, intraluminal polypoid mass, or an exophytic echogenic mass. It is usually not associated with the presence of calculi, as in cases of primary gallbladder malignancy.29

CT may also show focal thickening of the gallbladder wall, intraluminal polypoid mass, or an exophytic mass that usually enhances after administration of contrast (Figure 31-16). Some cases may involve the biliary tree, causing bile ductal dilatation.30

On MRI, metastatic lesions of the gallbladder may appear as hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted images and hypointense to isointense on T1-weighted images; it usually enhances after intravenous injection of contrast.31

Pancreas

The pancreas is rarely a site of metastatic disease, being found at autopsy in 3% to 12% of patients with disseminated malignant disease.32 The most common primary tumor associated with solitary pancreatic metastases is renal cell carcinoma. Other primary malignancies that may metastasize to the pancreas include lung, stomach, breast, colon, esophageal, melanoma, and lymphoma.33

According to Thompson and Heffess,34 renal cell carcinoma metastatic disease to the pancreas may occur many years after nephrectomy with an average of 8.4 years (range 0.5-27 yr); they are usually potentially amenable to surgery. Thus, patients must be followed closely because most patients with pancreatic metastases are asymptomatic with the lesions usually being detected incidentally on surveillance CT scans. Alternatively, symptomatic patients may present with abdominal pain, back pain, nausea, weight loss, and jaundice. In rare cases, it may cause acute pancreatitis.

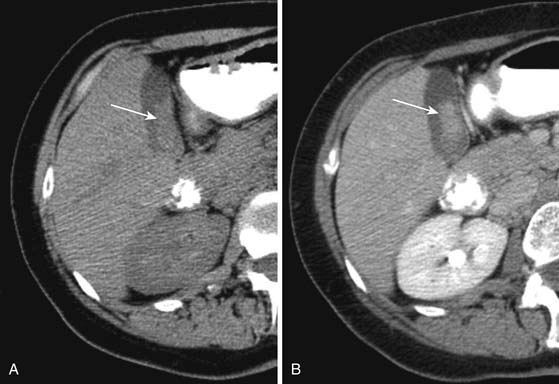

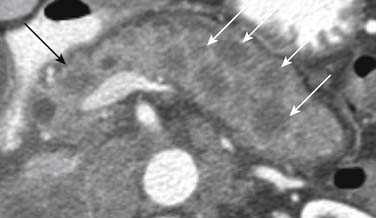

Metastatic pancreatic involvement manifests as a solitary focal mass without a predilection for a particular part of the pancreas, multiple nodules within the pancreas, or diffuse enlargement of the pancreas.35 On US, single or multiple metastatic solid lesions usually appear more hypoechoic than the remainder of the pancreatic parenchyma.36 Circumscribed lesions may appear isodense or, more often, slightly hypodense compared with the normal pancreatic parenchyma on unenhanced CT images. After intravenous injection of contrast, most pancreatic metastases appear as single or multiple enhancing low-attenuation lesions (Figure 31-17). A rim enhancement with heterogeneous areas of central low attenuation may be observed in large lesions whereas smaller lesions enhance more homogeneously (Figure 31-18). Conversely, metastases from renal cell carcinoma appear as intense-enhancing lesions in the arterial phase of contrast enhancement (Figure 31-19). In addition, attention should be given to the CT protocol used in the surveillance of renal cell carcinoma patients. According to Ng and associates,37 smaller pancreatic metastases from renal cell carcinoma, ranging from 0.6 to 11 cm in diameter, enhance most conspicuously during the early arterial phase of enhancement, beginning 25 seconds from the start of injection. The enhancement is less pronounced on the 60-second portal-phase images and may even fail to be appreciated on the 120-second delayed-phase images. On MRI, pancreatic lesions are usually hypointense on unenhanced T1-weighted images, moderately hyperintense on T2-weighted images, and enhance after intravenous injection of contrast.38

Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands are a frequent site of metastatic disease. They are the fourth most common site after lungs, liver, and bones. At autopsy, adrenal metastases are found in up to 27% of patients dying with an epithelial malignancy.32 Common sites of origin of adrenal gland metastases include the lung, breast, melanoma, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, pancreas, and thyroid.

Metastases are the most common malignant lesions involving the adrenal glands. In patients with a known underlying malignancy, an adrenal mass may be a metastasis but also could be an unrelated benign lesion. Imaging studies may help in differentiating between them. Patients with adrenal metastases are usually clinically silent. However, in some cases, it may present as hypoadrenalism.39

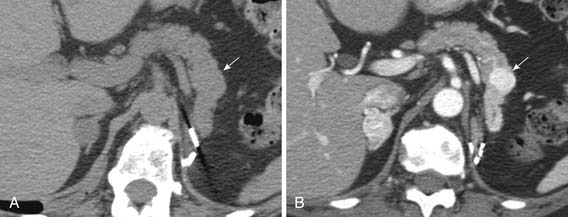

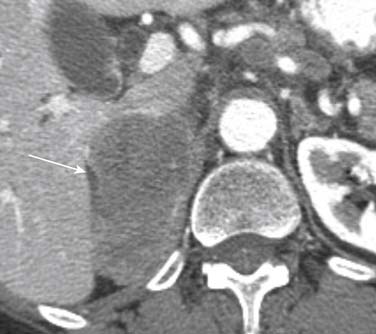

The radiographic appearance of adrenal metastases is not specific. They may be unilateral or bilateral, large or small. Adrenal metastases that are smaller than 2 cm are usually difficult to be diagnosed by US. In addition, US is limited in the differentiation of benign and malignant adrenal masses.40

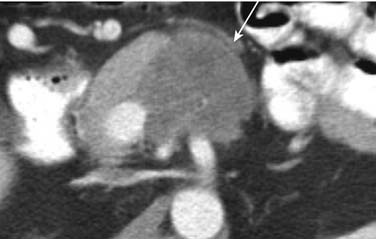

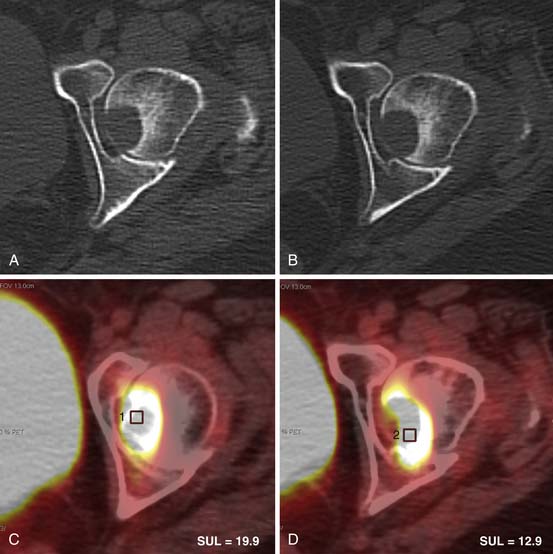

On CT, small adrenal metastases are usually well-defined, round or ovoid lesions with a thin rim and homogeneous density. Conversely, larger adrenal metastases may be lobulated or irregular in shape, with a heterogeneous appearance due to areas of necrosis, hemorrhage, or calcifications (Figures 31-20 and 31-21). The demonstration of the presence of fat in an adrenal mass allows the differential diagnosis between an adrenal adenoma and an adrenal metastasis that does not contain fat. The threshold of 10 HU in an unenhanced CT scan has a sensitivity of 79% and a specificity of 96% for the diagnosis of adrenal adenomas.41 After intravenous administration of contrast material, both the adrenal adenoma and the adrenal metastases enhance, but adenomas have a faster washout. The use of a percentage enhancement washout with a threshold of more than 60% on delayed enhanced scans performed at 15 minutes after the intravenous injection of contrast has a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 92% for the diagnosis of adrenal adenomas.42

On MRI, adrenal metastases usually demonstrate low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. It usually enhances after the intravenous administration of contrast material. The most accurate MRI technique for distinguishing an adenoma from a metastasis is chemical-shift imaging. Owing to its high fat content, adrenal adenomas demonstrate signal loss on out-of-phase images that is not present with adrenal metastasis.43

Key Points Adrenal glands

• The adrenal glands are the fourth most common site of metastatic disease after lungs, liver, and bones.

• Adrenal metastases may be found in up to 27% of patients dying with an epithelial malignancy at autopsy.

• Common sites of origin of adrenal glands metastases include the lung, breast, melanoma, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, pancreas, and thyroid.

Kidneys

Renal metastases constitute a significant percentage of kidney lesions found at autopsy. The kidney is the fifth most common site for metastatic solid tumors, following the lung, liver, bones, and adrenal glands. Renal metastases may be seen in up to 20% of patients dying of malignancy.44

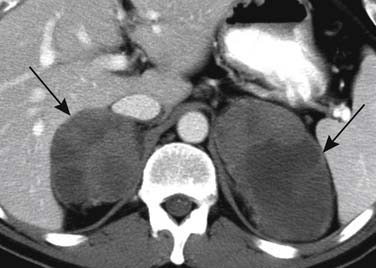

The most common primary tumors to metastasize to the kidneys are from the lung, breast lymphoma, melanoma, and gastrointestinal tract. Most renal metastases are usually clinically silent but some patients may present with microscopic or gross hematuria. Metastatic renal lesions may present as single or multiple cortical nodules and can be unilateral or bilateral. Renal metastases rarely manifest as intraluminal filling defects.45

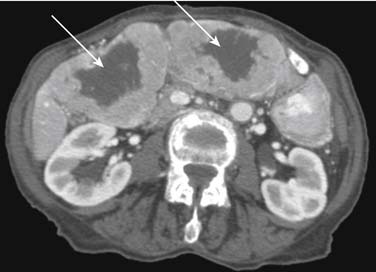

On US, renal metastases usually appear as homogeneous hypoechoic masses. However, some metastases may appear heterogeneous or echogenic.46 On unenhanced CT, renal metastases are generally small and multiple isodense or slightly hypodense lesions compared with the renal parenchyma. They are usually hypovascular and present mild enhancement after intravenous injection of contrast (Figures 31-22 and 31-23). Other features include an irregular thickened wall and a blurred margin with the normal renal parenchyma. Tumor invasion of the renal vein and extension into the inferior vena cava are rare with metastatic lesions.47 When the primary tumor is lymphoma, the renal involvement from lymphoma may have several different appearances. The most common presentation is multiple, bilateral, round, soft tissue density lesions that also enhance less than the normal renal parenchyma. However, a solitary mass or diffuse infiltration of the kidney by lymphoma may also be seen.48 On MRI, renal metastases usually demonstrate low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. It usually presents a mild enhancement after the intravenous administration of contrast material.47

Key Points Kidneys

• The kidneys are the fifth most common site for metastatic solid tumors, following the lung, liver, bones, and adrenal glands.

• Renal metastases may be seen in up to 20% of patients dying of malignancy.

• The most common primary tumors to metastasize to the kidneys are from the lung, breast lymphoma, melanoma, and gastrointestinal tract.

Urinary Bladder

The bladder is not a common site for metastasis and often goes undiagnosed in the clinical follow-up of cancer patients. Metastases to the bladder represent no more than 3% of all malignant bladder tumors.49 Urinary bladder involvement by a secondary tumor occurs either as a metastasis or by direct extension. It originates most commonly from primary tumors in the genitourinary tract, such as prostate and cervical sites, and from the colon and rectum. Of the malignancies arising from distant foci, melanoma is the most common tumor followed by breast, lung, and gastric carcinoma. Radiographically, these tumors present as one or multiple mural masses projecting into the bladder lumen. However, in some cases, they may present as diffuse thickening of the bladder wall that can be revealed by US and CT.50

Female Genital Tract

Metastases to the female genital tract are uncommon. However, the most frequent metastatic sites for both extragenital and genital primaries are the ovaries and vagina. Secondary tumors to the uterus are very uncommon and account for fewer than 10% of all cases of metastases to the female genital tract from extragenital cancers.51 The most common genital primaries tumors to give metastases to the female genital tract are the uterine body and uterine cervix. The most common extragenital tumors to give metastases to the female genital tract include breast, colon, stomach, lung, melanoma, pancreas, and sarcomas.51

Ovaries

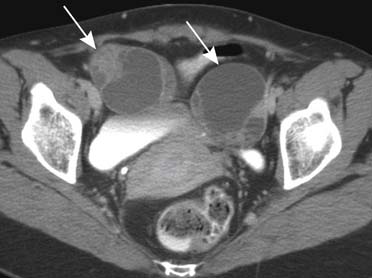

Metastatic tumors to the ovaries may represent 10% to 30% of malignant ovarian tumors.52 The most common tumors that metastasize to the ovary originate from the gastrointestinal tract, breast, gynecologic organs, lung, and melanoma.52 The term Krukenberg’s tumor is usually used to describe bilateral ovarian metastases consisting of solid portions and variable amounts of fluid-filled structures and characterized by mucin-producing signet-ring cells, most commonly originating from primary lesions in the gastrointestinal tract, in particular from carcinomas of the stomach (Figure 31-24).53

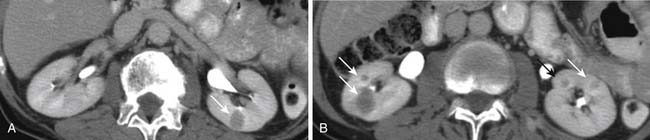

Colon carcinoma is one of the most frequent primary sites metastasizing to the ovary. Approximately 3% to 8% of female patients with colon carcinoma will develop metastases to the ovaries and between 6% and 14% of women dying with colorectal cancer are found to have ovarian metastases at autopsy.54

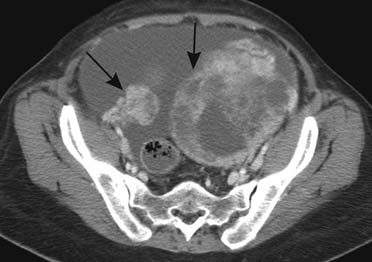

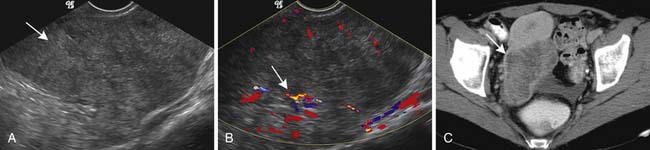

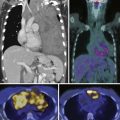

Radiographically, ovarian metastases are difficult to be differentiated from primary ovarian cancer. On US, ovarian metastastic lesions appear as complex masses with mixed echogenicity due to areas of soft tissue and cystic components.55 On CT, ovarian metastases frequently appear as heterogeneous masses with solid and cystic areas. The solid areas enhance after the intravenous injection of contrast (Figures 31-25 and 31-26).56

On MRI, the signal intensity will vary according to the presence and extent of the solid and cystic components. The more solid areas present as low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and as intermediate to low signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Alternatively, the signal intensity of the cystic component will depend on the chemical composition of the cyst fluid. Whereas simple fluid cystic lesions present with low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images, some mucin-containing lesions appear as high signal intensity on T1-weighted images.57

Key Points Ovaries

• Metastatic tumors to the ovaries may represent 10% to 30% of malignant ovarian tumors.

• The most common tumors that metastasize to the ovary originate from the gastrointestinal tract, breast, gynecologic organs, lung, and melanoma.

• Krukenberg’s tumor is usually used to describe bilateral ovarian metastases consisting of solid and cystic portions, most commonly originating from primary lesions in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly from the stomach.

• Approximately 3% to 8% of female patients with colon carcinoma will develop ovarian metastases.

• Six percent to 14% of women dying with colorectal cancer are found to have ovarian metastases at autopsy.

Male Genital Tract, Prostate, and Testicles

Metastatic tumors to the male genital tract are rare. Secondary tumors account for 1.6% to 3% of solid malignancies encountered in surgical specimens from the genitourinary tract.58

Prostate

Secondary neoplasms of the prostate may be found in 0.5% to 5.6% of patients who died from cancer and in 2.1% of all neoplasms in surgical specimens.58 Prostate involvement by a secondary tumor occurs either as a metastasis or by direct extension from adjacent structures. The most common primary sites that can give metastases to the prostate include lung, gastrointestinal tract, melanoma, and pancreas, whereas tumors of the bladder and rectum usually reach the prostate by direct spread.59

Testicles

Secondary neoplasms of the testicles are most commonly an incidental finding at autopsy reported to be found in 0.5% of patients who have died of cancer. The most common primary sites that can give metastases to the testicles include the prostate, lung, melanoma, colon, kidney, urinary tract, and pancreas.60

1. Poste G., Fidler I.J. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis. Nature. 1980;283:139-146.

2. Fidler I.J. Critical determinants of metastasis. Semin Cancer Biol. 2002;12:89-96.

3. Yokota J. Tumor progression and metastasis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:497-503.

4. Blaszyk H., Hartmann A., Bjornsson J. Cancer of unknown primary: clinicopathologic correlations. APMIS. 2003;111:1089-1094.

5. Cameron G.R. The liver as a site and source of cancer. Br Med J. 1954;13:347-352.

6. Baker M.E., Pelley R. Hepatic metastases: basic principles and implications for radiologists. Radiology. 1995;197:329-337.

7. Wernecke K., Henke L., Vassallo P., et al. Pathologic explanation for hypoechoic halo seen on sonograms of malignant liver tumors: an in vitro correlative study. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:1011-1016.

8. Robison P.J. Imaging liver metastases: current limitations and future prospects. Br J Radiol. 2000;73:234-241.

9. Wernecke K., Rummeny E., Bongartz G., et al. Detection of hepatic masses in patients with carcinoma: comparative sensitivities of sonography, CT, and MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:731-739.

10. Quaia E., D’Onofrio M., Palumbo A., et al. Comparison of contrast-enhanced ultrasonography versus baseline ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography in metastatic disease of the liver: diagnostic performance and confidence. Eur Radiol. 2006;16:1599-1609.

11. Sica G.T., Ji H., Ros P.R. CT and MRI imaging of hepatic metastases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:691-698.

12. Kanematsu M., Kondo H., Goshima S., et al. Imaging liver metastases: review and update. Eur J Radiol. 2006;58:217-228.

13. Liu P.S., Francis I.R. Hepatic imaging for metastatic disease. Cancer J. 2010;16:93-102.

14. Mainenti P.P., Mancini M., Mainolfi C., et al. Detection of colo-rectal liver metastases: prospective comparison of contrast enhanced US, multidetector CT, PET/CT, and 1.5 Tesla MR with extracellular and reticulo-endothelial cell specific contrast agents. Abdom Imaging. 2010;35:511-521.

15. Valls C., Lopez E., Gumà A., et al. Helical CT versus CT arterial portography in the detection of hepatic metastasis of colorectal carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:1341-1347.

16. Imam K., Bluemke D.A. MR imaging in the evaluation of hepatic metastases. Magn Reson Imaging Clin North Am. 2000;8:741-756.

17. Namasivayam S., Martin D.R., Saini S. Imaging of liver metastases: MRI. Cancer Imaging. 2007;7:2-9.

18. Hussain S.M., Semelka R.C. Hepatic imaging: comparison of modalities. Radiol Clin North Am. 2005;43:929-947.

19. Semelka R.C., Schlund J.F., Molina P.L., et al. Malignant liver lesions: comparison of spiral CT arterial portography and MR imaging for diagnostic accuracy, cost, and effect on patient management. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1996;6:39-43.

20. Berge T. Splenic metastases. Frequencies and patterns. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1974;82:499-506.

21. Lam K.Y., Tang V. Metastatic tumors to the spleen. A 25-year clinicopathologic study. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:526-530.

22. Compérat E., Bardier-Dupas A., Camparo P., et al. Splenic metastases: clinicopathologic presentation, differential diagnosis, and pathogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:965-969.

23. Sauer J., Soblewski K., Dommish K. Splenic metastases—not a frequent problem, but an underestimate location of metastases: epidemiology and course. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135:667-671.

24. Federle M., Moss A.A. Computed tomography of the spleen. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1983;19:1-16.

25. Elsayes K.M., Narra V.R., Mukundan G., et al. MR imaging of the spleen: spectrum of abnormalities. Radiographics. 2005;25:967-982.

26. Yoon W.J., Yoon Y.B., Kim Y.J., et al. Metastasis to the gallbladder: a single-center experience of 20 cases in South Korea. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:4806-4809.

27. Shimkim P.M., Soloway M.S., Jaffe E. Metastatic melanoma of the gallbladder. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1972;116:393-395.

28. Nassenstein K., Kissler M. Gallbladder metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Onkologie. 2004;27:398-400.

29. Dong X.D., DeMatos P., Prieto V.G., Seigler H.F. Melanoma of the gallbladder: a review of cases seen at Duke University Medical Center. Cancer. 1999;85:32-39.

30. Takayama Y., Asayama Y., Yoshimitsu K., et al. Metastatic melanoma of the gallbladder. Comput Med Imaging Graph. 2007;31:469-471.

31. Yoshimitsu K., Honda H., Kaneko K., et al. Dynamic MRI of the gallbladder lesions: differentiation of benign from malignant. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1997;7:696-701.

32. Abrams H.L., Spiro R., Goldestein N. Metastases in carcinoma. analysis of 1000 autopsied cases. Cancer. 1950;3:73-85.

33. Adsay N.V., Andea A., Basturk O., et al. Secondary tumors of the pancreas: an analysis of a surgical and autopsy database and review of the literature. Virchows Arch. 2004;444:527-535.

34. Thompson L.D., Heffess C.S. Renal cell carcinoma to the pancreas in surgical pathology material. Cancer. 2000;89:1076-1088.

35. Klein K.A., Stephens D.H., Welch T.J. CT characteristics of metastatic disease of the pancreas. Radiographics. 1998;18:369-378.

36. Wernecke K., Peters P.E., Galanski M. Pancreatic metastases: US evaluation. Radiology. 1986;160:399-402.

37. Ng C.S., Loyer E.M., Iyer R.B., et al. Metastases to the pancreas from renal cell carcinoma: findings on three-phase contrast-enhanced helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:1555-1559.

38. Merkle E.M., Boaz T., Kolokythas O., et al. Metastases to the pancreas. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:1208-1214.

39. Sahagian-Edwards A., Holland J.F. Metastatic carcinoma to the adrenal glands with cortical hypofunction. Cancer. 1954;7(6):1242-1245.

40. DeAtkine A.B., Dunnick N.R. The adrenal glands. Semin Oncol. 1991;18:131-139.

41. Lee M.J., Hahn P.F., Papanicolaou N., et al. Benign and malignant adrenal masses: CT distinction with attenuation coefficients, size, and observer analysis. Radiology. 1991;179:415-418.

42. Caoili E.M., Korobkin M., Francis I.R., et al. Adrenal masses: characterization with combined unenhanced and delayed enhanced CT. Radiology. 2002;222:629-633.

43. Bilbey J.H., McLoughlin R.F., Kurkjian P.S., et al. MR imaging of adrenal masses: value of chemical-shift imaging for distinguishing adenomas from other tumors. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:637-642.

44. Hietala S.O., Wahlqvist L. Metastatic tumors to the kidney. A postmortem, radiologic and clinical investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh). 1982;23:585-591.

45. Wagle D.G., Moore R.H., Murphy G.P. Secondary carcinomas of the kidney. J Urol. 1975;114:30-32.

46. Choyke P.L., White E.M., Zeman R.K., et al. Renal metastases: clinicopathologic and radiologic correlation. Radiology. 1987;162:359-363.

47. Bailey J.E., Roubidoux M.A., Dunnick N.R. Secondary renal neoplasms. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23:266-274.

48. Cohan R.H., Dunnick N.R., Leder R.A., Baker M.E. Computed tomography of renal lymphoma. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990;14:933-938.

49. Morichetti D., Mazzucchelli R., Lopez-Beltran A. Secondary neoplasms of the urinary system and male genital organs. BJU Int. 2009;104(6):770-776.

50. Velcheti V., Govindan R. Metastatic cancer involving bladder: a review. Can J Urol. 2007;14:3443-3448.

51. Mazur M.T. Metastases to the female tract. Analysis of 325 cases. Cancer. 1984;53:1978-1984.

52. Yada-Hashimoto N., Yamamoto T., Kamiura S., et al. Metastatic ovarian tumors: a review of 64 cases. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:314-317.

53. Young R.H. From Krukenberg to today: the ever present problems posed by metastatic tumors in the ovary: part I. Historical perspective, general principles, mucinous tumors including the krukenberg tumor. Adv Anat Pathol. 2006;13:205-227.

54. Omranipour R., Abasahl A. Ovarian metastases in colorectal cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19:1524-1528.

55. Moyle J.W., Rochester D., Sider L., et al. Sonography of ovarian tumors: predictability of tumor type. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983;141:985-991.

56. Megibow A.J., Hulnick D.H., Bosniak M.A., Balthazar E.J. Ovarian metastases: computed tomographic appearances. Radiology. 1985;156:161-164.

57. Iyer V.R., Lee S.I. MRI, CT, and PET/CT for ovarian cancer detection and adnexal lesion characterization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:311-321.

58. Bates A.W., Baithun S.I. The significance of secondary neoplasms of the urinary and male genital tract. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:640-647.

59. Bates A.W., Baithun S.I. Secondary solid neoplasms of the prostate: a clinico-pathological series of 51 cases. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:392-396.

60. Ulbright T.M., Young R.H. Metastatic carcinoma to the testis: a clinicopathologic analysis of 26 nonincidental cases with emphasis on deceptive features. Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1683-1693.