Metal poisoning

Metals associated with poisoning

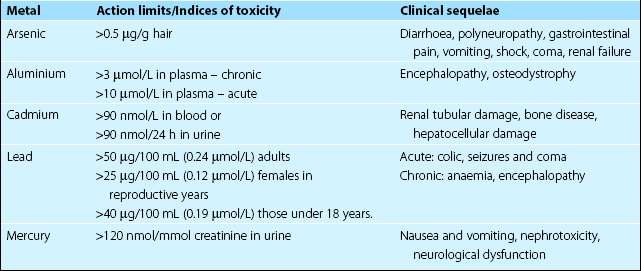

The metals that give rise to clinical symptoms in man are shown in Table 61.1. Apart from the occasional suicide or murder attempt, most poisonings are due to environmental contamination or administration of drugs, remedies or cosmetics that contain metal salts. There are three main clinical effects of exposure to toxic metals. These are: renal tubular damage, gastrointestinal erosions and neurological damage.

Diagnosis

Blood, plasma, serum or urine can all be used for measurement, and in some cases it may also be helpful to measure the metal concentration in other tissues such as hair. The action limits for metals in plasma and urine are shown in Table 61.1.

Treatment

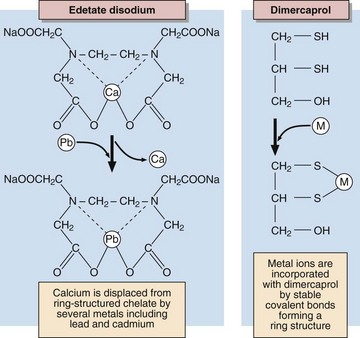

As with most poisons, treatment consists of removal of the source of the metal and increasing the elimination from the body, while correcting deranged physiological or biological mechanisms. Removal of the source may require that a person be removed from a contaminated site or workplace or that the use of a medication or cosmetic be discontinued. Elimination of heavy metals is achieved by treatment with chelating agents that bind the ions and allow their excretion in the urine (Fig 61.1).

Common sources

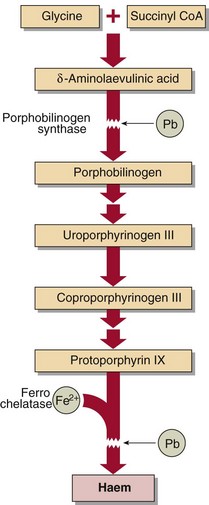

Biochemical evidence of lead poisoning is by the finding of raised protoporphyrin levels in the erythrocytes due to the inhibition of a number of the synthetic enzymes of the haem pathway by lead (Fig 61.2). A clinical sign is the appearance of a blue line on the gums.

Fig 61.2 Effects of lead on haem synthesis. Lead (Pb) inhibits porphobilinogen synthase and Fe2+ incorporation into haem, resulting in increased levels of δ-aminolaevulinic acid and coproporphyrin in urine and protoporphyrin in erythrocytes.

Lead is measured in whole blood or in urine (Table 61.1). Excretion can be enhanced using chelating agents such as NaEDTA, dimercaprol or N-acetyl-penicillamine. Because of their high toxicity the use and handling of organic lead compounds, such as tetra-ethyl-lead, the anti-knocking agent in petrol, is strictly regulated by law and they are being replaced by alternative compounds.

Mercury

Diagnosis is by estimation of blood and urine mercury concentrations (Table 61.1). Long-term monitoring of exposure, such as may be necessary with those working with dental amalgam, may be carried out using hair or nail clippings.

Aluminium

Diagnosis is by measurement of aluminium in a plasma specimen (Table 61.1). Aluminium content of bone biopsy material is also used, with levels greater than 100 µg/g dry weight indicating accumulation.

Cadmium

In diagnosis, indicators of renal damage, in particular β2-microglobulin in urine, can be used to monitor the effects. Blood and urine cadmium estimates (Table 61.1) will give an objective index of the degree of exposure, and, in some cases, the cadmium content of renal biopsy tissue may be useful.