CHAPTER 5 Metabolism

Endocrinology

Diabetes

Pathophysiology

CNS. Neuropathy impairs neuromuscular transmission. Decreased response to tetanic stimulation.

GI. Delayed gastric emptying and gastroparesis are secondary to autonomic neuropathy.

Alberti regimen (Alberti and Thomas 1979). Safe because glucose and insulin are provided together.

Guidelines for the Management of Diabetic Patients Undergoing Surgery

British National Formulary 59

Cushing’s syndrome

Postoperative problems. Sleep apnoea (20%), steroids risk wound breakdown and infection.

Acromegaly

This is characterized by excess growth hormone secretion resulting in soft tissue overgrowth.

Surgery. Via transfrontal craniotomy or transethmoidal approach.

Perioperative: 25% have enlarged thyroid which may compress the trachea.

Postoperative. Addison’s disease, hypothalamic damage, CSF leak, diabetes insipidus, sleep apnoea.

Thyroid disease

Hyperthyroidism

Symptoms. Excitability, tremor, sweating, weight loss, palpitations, exophthalmos.

Diagnosis. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free T3/T4, resin uptake, thoracic inlet X-ray/CT.

Hypoparathyroidism

Severe hypocalcaemia indicated by:

Trousseau’s sign. Tourniquet inflated above arterial pressure causes carpopedal spasm.

Chvostek’s sign. Percussion of the facial nerve produces facial muscle contraction.

Hyperparathyroidism

Carcinoid tumour

Perioperative Steroid Supplementation

Anaesthetic implications

There is no evidence that aiming for cortisol levels higher than normal baseline values is of any benefit in patients with suppressed HPA function (i.e. those on steroid therapy). The current recommendations are summarized in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Recommendations for perioperative steroid supplementation

| Preoperative | Additional steroid cover | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients currently taking steroids | ||

| <10 mg/day | Assume normal HPA function | Additional steroid cover not required |

| >10 mg/day | Minor surgery | 25 mg hydrocortisone on induction |

| Moderate surgery | Usual preoperative steroids + 25 mg hydrocortisone on induction + 100 mg/day for 24 h | |

| Major surgery | Usual preoperative steroids + 25 mg hydrocortisone on induction + 100 mg/day for 48–72 h | |

| Patients stopped taking steroids | ||

| <3 months | Treat as if on steroids | |

| >3 months | No perioperative steroids necessary | |

Alberti K.G., Thomas D.J. The management of diabetes during surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1979;51:693-703.

Annane D., Bellissant E., Bollaert P.E., et al. Corticosteroids in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in adults: a systematic review. JAMA. 2009;301:2362-2375.

Bacuzzi A., Dionigi G., Del Bosco A., et al. Anaesthesia for thyroid surgery: perioperative management. Int J Surg. 2008;6:S8.

British National Formulary 59. http://bnf.org.bnf/extra/current/450062.htm. The reader is reminded that the BNF is constantly revised; for the latest guidelines please consult the current edition at www.bnf.org

Holdcroft A. Hormones and the gut. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:58-68.

Lipshutz A.K.M., Gropper M.A. Perioperative glycemic control – an evidence-based review. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:408-421.

Malhotra S., Sodhi V. Anaesthesia for thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2007;7:55-58.

Mihai R., Farndon J.R. Parathyroid disease and calcium metabolism. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:29-43.

NICE. Intraoperative nerve monitoring during thyroid surgery, 2008. March National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence www.nice.org.uk/IPG255distributionlist ©c

Nicholson G., Burrin J.M., Hall G.M. Peri-operative steroid supplementation. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:1091-1104.

Pace N., Buttigieg M. Phaeochromocytoma. BJA CEPD Rev. 2003;3:20-23.

Robertshaw H.J., Hall G.M. Diabetes mellitus: anaesthetic management. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:1187-1190.

Smith M., Hirsh N.P. Pituitary disease and anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:3-14.

Vaughan D.J., Brunner M.D. Anesthesia for patients with carcinoid syndrome. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1997;35:129-142.

Webster N.R., Galley H.F. Does strict glucose control improve outcome? Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:331-334.

Malignant hyperthermia

Signs

Early. Tachypnoea, rise in end-tidal CO2, tachycardia, hypoxaemia, fever (>2°C.h−1), masseter spasm.

Triggering factors

Pathophysiology

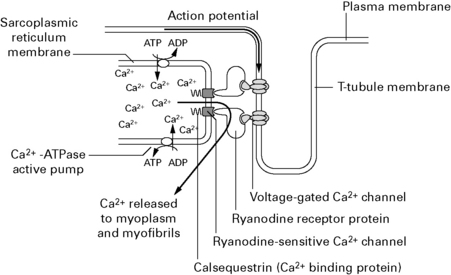

Muscle contraction results from flooding of the cytoplasm by Ca2+ entering across the plasma membrane through voltage-gated Ca2+ channels and released from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) through ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ channels (Fig. 5.1). These channels occur in pairs where folds in the SR meet the sarcolemma of the t-tubule. The ryanodine (Ry1) receptor is a large protein molecule comprising four identical monomers that sits between the two Ca2+ channels. Depolarization results in charge movement in the voltage-operated Ca2+ channels which activates the Ry1 receptor to open and Ca2+ is released into the myoplasm. Volatile anaesthetic agents may increase the leak of Ca2+ through the Ry1 protein, which does not cause clinical symptoms. In myopathic muscle, this leak may be sufficient to trigger a final common pathway with activation of contractile elements, ATP hydrolysis, O2 consumption, CO2 production, lactate and heat generation, uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, and cell breakdown with loss of myoglobin, CPK and K+ to cause the clinical picture of MH.

Guidelines for the Management of a Malignant Hyperthermia Crisis

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2007

Take measures to halt the MH process

Perioperative management of patients with known MH

Dental patient. Any major surgery must be performed in hospital.

Adnet P., Lestavel P., Krivosic-Horber R. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:129-135.

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Guidelines for the management of a malignant hyperthermia crisis, 2007. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland

Hopkins P.M. Malignant hyperthermia. Advances in clinical management and diagnosis. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:118-128.

Robinson R.L., Hopkins P.M. A breakthrough in the genetic diagnosis of malignant hyperthermia. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:166-168.

Anaesthesia for the morbidly obese patient

Definition

Body mass index (BMI) = weight (kg)/height (m)2. Normal = 22–28 kg/m2.

Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic changes

Drug doses

Some drug dosages may need to be altered for morbidly obese patients (see Table 5.2).

| Unchanged dose per total weight | Unchanged dose per lean weight | Larger absolute dose but smaller dose per total weight |

|---|---|---|

| Midazolam | Vecuronium | Thiopentone |

| Diazepam | Propofol | |

| Suxamethonium | Remifentanil | |

| Pancuronium | ||

| Atracurium | ||

| Fentanyl | ||

| Alfentanil | ||

| Lignocaine |

Perioperative management

Regional/local anaesthesia

Never perform regional/local block unless able and ready to convert to a GA.

Perioperative Management of the Morbidly Obese Patient

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland 2007

Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland: Peri-Operative Management of the Morbidly Obese Patient. Reproduced with the kind permission of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, 2007.

Cheah M.H., Kam P.C.A. Obesity: basic science and medical aspects relevant to anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2005;60:1009-1021.

Lotia S., Bellamy M.C. Anaesthesia and morbid obesity. Contin Edu Anaesth, Crit Care Pain. 2008;8:151-156.

NICE. Obesity – guidance on the prevention, identification, assessment and management of overweight and obesity in adults and children, 2006. December National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence www.nice.org.uk/CG043

Ogunnaike B.O., Jones S.B., Jones D.B. Anesthetic considerations for bariatric surgery. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1793-1805.

Pieracci F.M., Barie P.S., Pomp A. Critical care of the bariatric patient. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1796-1804.

Saravanakumar K., Rao S.G., Cooper G.M. Obesity and obstetric anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:36-48.

Metabolic response to stress

The metabolic response is initiated by:

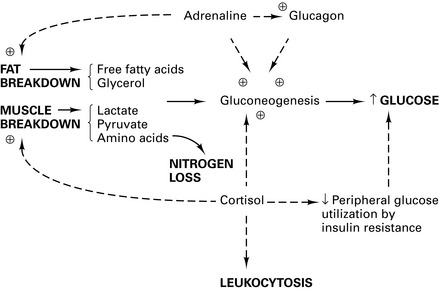

This neurohumoral response (Fig. 5.2) converges on the hypothalamus to trigger:

Thermoregulation

Physiology

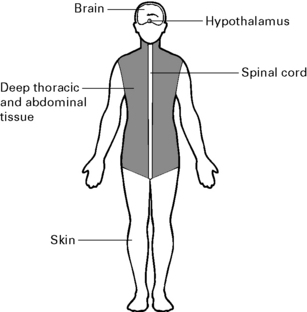

Afferent input

Perioperative hypothermia

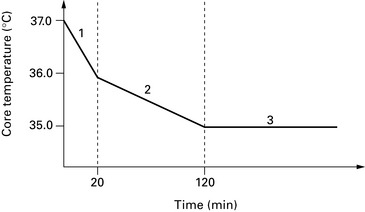

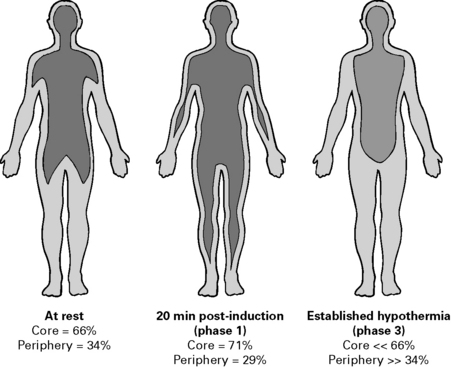

Perioperative hypothermia develops in three phases (see Figs 5.4 and 5.5):

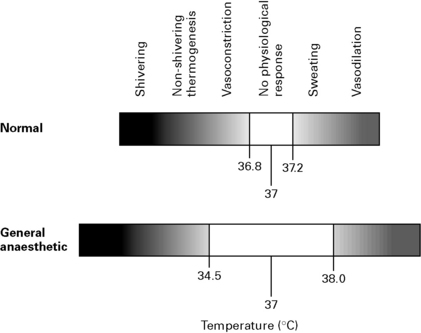

Effects of general anaesthesia

GA inhibits behavioural responses to hypothermia, decreases metabolic rate, inhibits hypothalamic function and attenuates homeostatic reflexes. The threshold at which compensatory mechanisms to hypothermia are activated is lowered by about 2.5°C and the threshold for mechanisms protecting from hyperthermia is increased by about 1.0°C, i.e. widening of thresholds with ↑ MAC (Fig. 5.7).

Thermoregulatory thresholds vary depending upon the anaesthetic agents used:

Effects of hypothermia

CVS

Metabolism

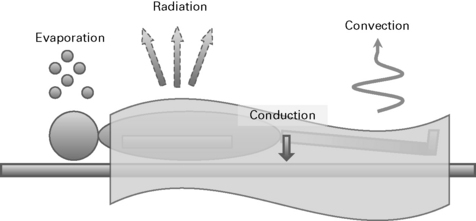

Techniques to avoid heat loss

Inadvertent Perioperative Hypothermia

NICE Clinical Guideline 65, April 2008

Preoperative phase

Intraoperative phase

Buggy D.J., Crossley A.W. Thermoregulation, mild perioperative hypothermia and post-anaesthetic shivering. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:615-628.

NICE. Inadvertent perioperative hypothermia. NICE clinical guideline 65 www.nice.org.uk/CG065, 2008.

Sessler D.I. Temperature monitoring and perioperative thermoregulation. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:318-338.

mismatch and hypoxia, obstructive sleep apnoea progressing to Pickwickian syndrome (cor pulmonale, hypoxia, hypercapnia, polycythaemia). Increased O2 consumption and low FRC cause faster desaturation.

mismatch and hypoxia, obstructive sleep apnoea progressing to Pickwickian syndrome (cor pulmonale, hypoxia, hypercapnia, polycythaemia). Increased O2 consumption and low FRC cause faster desaturation.