10.1 Metabolic emergencies

Physiology and pathogenesis

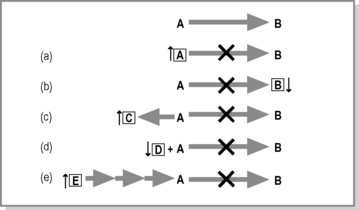

The process by which living matter is built up (anabolism) or broken down (catabolism) is termed metabolism. Strictly speaking, an inborn error of metabolism (IEM) is an inherited defect in a metabolic pathway or enzyme. Generally, there is a defect in an enzyme that catalyses the conversion of one organic compound to another. However, not all defects in metabolic pathways give rise to pathology. Figure 10.1.1 shows that compound A is converted to B. If the enzyme that catalyses the reaction is not present or is functioning poorly, this can affect the body in any one of the following ways.

There is a deficiency of B, which results in cellular dysfunction – example: Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, a disorder of cholesterol biosynthesis.

There is a deficiency of B, which results in cellular dysfunction – example: Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome, a disorder of cholesterol biosynthesis. Excess A results in accumulation of metabolite E earlier in the pathway, which is toxic – example: maple syrup urine disease.

Excess A results in accumulation of metabolite E earlier in the pathway, which is toxic – example: maple syrup urine disease. Excess A is excreted by reacting/conjugating with D, which results in deficiency of D – example: carnitine deficiency in fatty acid oxidation defects.

Excess A is excreted by reacting/conjugating with D, which results in deficiency of D – example: carnitine deficiency in fatty acid oxidation defects.The pathology seen in an IEM can result from any of the processes outlined in Figure 10.1.1, but in fact most IEM are the result of more than one mechanism. Genetic defects can also occur in the support processes of metabolic pathways such as transport proteins, enzyme chaperones and enzyme complex assembly proteins, which result in the block of a metabolic process and thus pathology.

Clinical features

The clinical features and presentations of IEM are many and varied due to the diverse nature of the enzymes and processes affected; however, Table 10.1.1 shows that there are a number of common features that should alert the clinician to the possibility of an IEM.

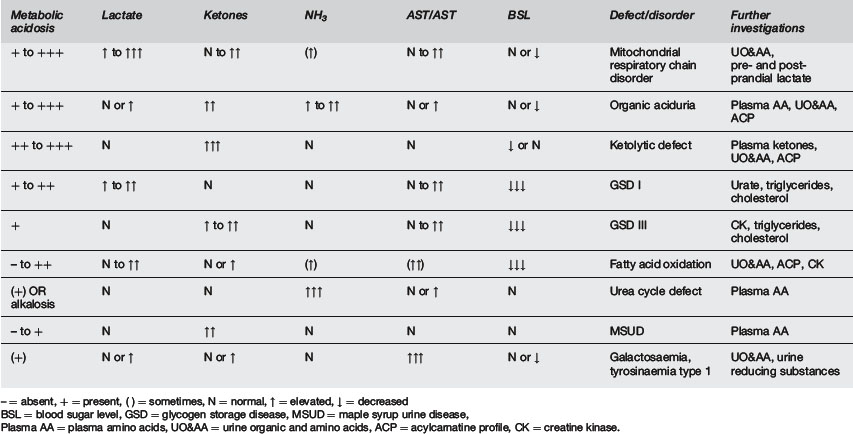

Table 10.1.2 can be used as a guide to identifying an IEM in the ED:

| Clinical features | Biochemical features |

|---|---|

| Overwhelming illness in the neonatal period Recurrent vomiting Coma or encephalopathy Apnoea and/or seizures Failure to thrive or malnutrition Presence of an unusual odour Not responding to usual treatment Unusual odour FH of neonatal or infant death, SIDS or acute life threatening event (ALTE) |

Acute acidosis (with raised anion gap) Hypoglycaemia Lactic acidosis (normal perfusion) Ketoacidosis Acute hepatic dysfunction Coagulopathy |

IEM are broken down into a number of groups of conditions, all of which affect a common metabolic pathway. The groups of IEM that are likely to present to the ED are outlined in Table 10.1.1, including the common presenting features of each.

Investigation

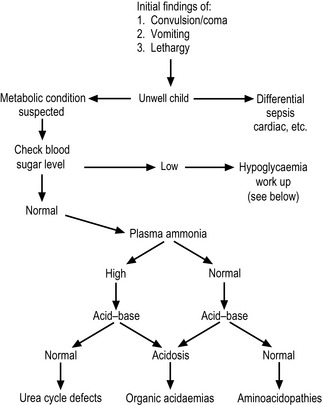

Once the results of the initial investigations are available, a possible diagnosis and further investigations may be suggested, depending on the profile (Table 10.1.3 and Figure 10.1.2). However, if this not helpful, all of the following second line investigations should be performed:

| Blood | plasma amino acids, plasma ketones, acylcarnitine profile, creatine kinase, urate. |

| Urine | organic and amino acids. |

Management

Correction of altered homeostasis

Hypoglycaemia and metabolic acidosis are the two most common biochemical abnormalities seen in IEM.

Chronic presentations

There are a number of IEM that do not present with acute symptoms, but in a progressive degenerative manner, frequently multisystemic. The early symptoms and signs in these conditions can be common presentations or incidental findings in the ED (Table 10.1.4). Appreciation of their significance can allow for early diagnosis and in a growing number of conditions an improved outcome for the patient, through innovative new therapies such as enzyme replacement therapy (ERT) and, in the future, gene and stem cell therapy.

Oligosaccharides

Oligosaccharides

Oligosaccharides

Oligosaccharides

Urine MPS screen

MPS = mucopolysaccharidoses.