Mesenchymal Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Erinn Downs-Kelly

Brian P. Rubin

John R. Goldblum

Introduction

Although epithelial neoplasms predominate in the tubal gut, a variety of mesenchymal neoplasms may originate from or secondarily involve the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Given the rarity of these lesions and the fact that many have overlapping histologic features, their accurate classification can be challenging, especially in the setting of limited endoscopic biopsy material. That said, knowledge of a few key details can help narrow an often wide differential diagnosis. For example, mesenchymal neoplasms have favored anatomic locations within the tubal gut as well as characteristic sites of involvement or origin from the various components of the gastrointestinal tract (mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, or serosa), as described in Table 30.1. An important consideration when faced with an apparent spindle cell lesion involving the tubal gut is to exclude the possibility of a sarcomatoid or spindle cell carcinoma. In this instance, a panel of cytokeratin stains can usually correctly identify the lesion as a carcinoma. It is also important to remember that gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) account for as many as 90% of clinically significant mesenchymal neoplasms within the GI tract; for that reason, GISTs will receive major emphasis within this chapter.

Table 30.1

Favored Anatomic Locations and Involvement by Mesenchymal Neoplasms of the Gastrointestinal Tract

| Neoplasm | Most Common Anatomic Location | Most Common Layer Involved within the Gastrointestinal Tract |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) | Stomach (60%), jejunum and ileum (30%) | Muscularis propria and submucosa |

| Schwannoma | Stomach | Muscularis propria and submucosa |

| Gangliocytic paraganglioma | Duodenum | Submucosa |

| Polypoid ganglioneuroma | Colon | Mucosa |

| Mucosal perineurioma | Colon | Mucosa |

| Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma | Colon | Mucosa |

| Granular cell tumor | Esophagus | Submucosa |

| Leiomyoma | Colon and rectum Esophagus |

Muscularis mucosae Muscularis propria |

| Lipoma | Colon | Submucosa |

| Glomus tumor | Stomach | Muscularis propria |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | Intraabdominal | Mesentery and omentum |

| Plexiform fibromyxoma | Stomach | Muscularis propria |

| Perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) | Colon and rectum | Variable; mucosa and submucosa or entire thickness of bowel wall |

| Clear cell sarcoma–like tumor | Small bowel | Entire thickness of the bowel wall |

Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors (GISTs)

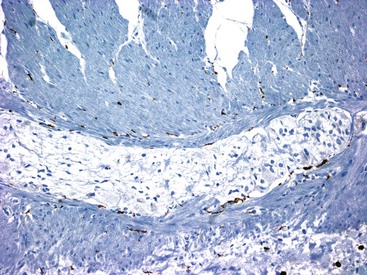

Although GISTs were once believed to represent smooth muscle neoplasms,1–3 it has now been established through ultrastructural and immunophenotypic studies that they arise from either the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) or the precursors of those cells.4–10 ICCs are present throughout the wall of the GI tract. They function to coordinate peristalsis by generating and propagating electrical slow waves of depolarization.7–9,11,12 Although the location and density of ICC vary, in most portions of the GI tract, the largest density occurs around the circumference of the myenteric plexus with extension between the inner and outer layers of the muscularis propria13 (Fig. 30.1).

KIT (CD117) has been identified as a receptor tyrosine kinase that plays a role in the development and maintenance of ICCs6,14: the binding of KIT ligand leads to phosphorylation of signal transduction proteins that modulate cell proliferation and inhibit apoptosis.15,16 Mice that are deficient in Kit or in stem cell factor (the normal ligand for Kit) do not have ICCs and show evidence of intestinal dysmotility.17 Activating mutations in KIT or in platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA) have been identified in as many as 80% and 10% of GISTs, respectively, and these mutually exclusive gain-of-function mutations play a fundamental role in GIST development by leading to constitutive activation.18–23

Clinical Features

Approximately 4500 to 6000 GISTs are diagnosed annually in the United States.18,19 GISTs can arise at almost any age, including childhood, but are most common in middle-aged and elderly patients, with approximately 75% diagnosed in patients older than 50 years.20–22 They may arise anywhere in the GI tract but are most common in the stomach (60%), followed by the jejunum and ileum (30%), the duodenum (5%), and the colorectum (<5%).23,24 Very few cases have been described in the esophagus25 or appendix.26,27 GISTs may also occur as primary tumors outside the GI tract, in the retroperitoneum or abdomen (e.g., omentum or mesentery); such tumors are referred to as extraintestinal GISTs.28,29

The presenting manifestations of GIST depend on the site of involvement in the GI tract, the size of the tumor, and the portion of the gut wall in which the tumor is located. A significant number of tumors are asymptomatic and are found incidentally at surgery performed for other reasons.30,31 The most common symptoms are GI bleeding with subsequent anemia, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and weight loss.32 Signs and symptoms may lead to endoscopy and biopsy. In some cases, a histologic diagnosis of GIST can be made if a deep endocscopic biopsy is obtained or if the neoplasm infiltrates the overlying mucosa. Radiographic imaging studies, including use of barium contrast, computed tomography, and endoscopic ultrasound, are commonly used for evaluation and diagnosis of these neoplasms.33,34 In addition, GISTs can be diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology.35

The behavior of GISTs ranges from benign to malignant. In adults, GIST behavior can be predicted by anatomic site, tumor size, and mitotic activity.18,20,23,36,37 Metastases usually develop within 2 years of diagnosis, and the expected pattern of metastatic spread is to the liver and serosa within the abdominal cavity.20 Rare cases of metastatic disease outside the abdominal cavity have been seen, most commonly in the lungs, bone, soft tissue, and, very rarely in advanced cases, intracranial sites.20,38,39 Historically, nodal metastases in GISTs have been extremely uncommon (<1% of cases). However, more recent studies show that succinate dehydrogenase (SDH)-deficient GISTs (described later) have a propensity for nodal metastases.40–42

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Features

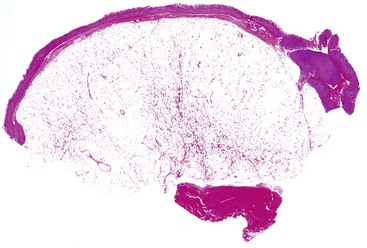

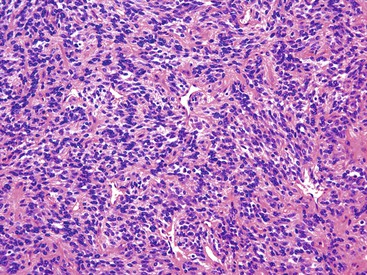

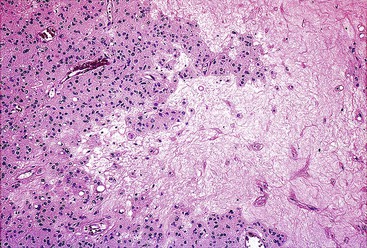

Most GISTs are uninodular and centered on the bowel wall; however, multifocal nodules have been described, especially in the pediatric population and in GIST syndromes. The tumor may ulcerate the overlying mucosa or grow exophytically and protrude toward the serosal aspect. Some GISTs are predominantly extramural and may be attached to the serosa of the tubal gut by only a thin stalk of tissue. On cut section, lesions may show areas of hemorrhage, necrosis, or cystic change—features that are not indicative of malignancy in GISTs (Fig. 30.2). The histomorphology varies greatly and includes pure spindle cell, pure epithelioid cell, and mixed spindle and epithelioid cell types.18 Epithelioid and mixed cell type GISTs are most commonly encountered in the stomach.43,44

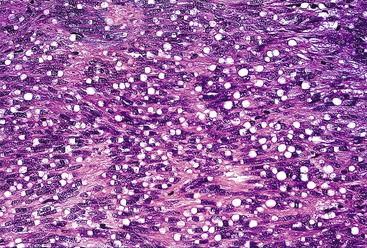

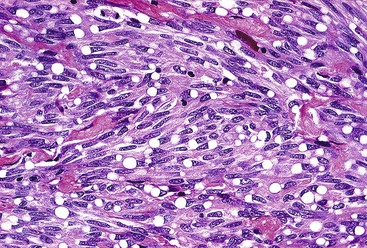

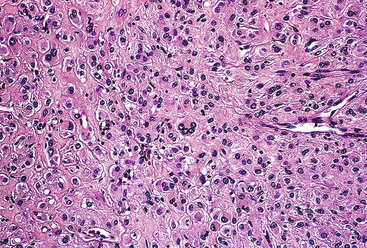

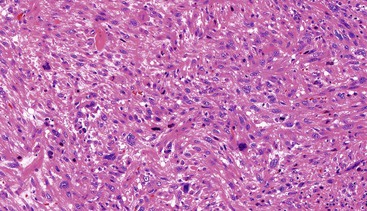

Spindle cell GISTs are composed of uniform, elongated cells that are consistent in size and shape. The cells have nuclei with evenly dispersed chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, and moderate amounts of pale to eosinophilic fibrillary cytoplasm (Fig. 30.3). Particular to gastric GISTs is the frequent presence of perinuclear vacuoles (due to fixation artifact) that indent the nucleus at one pole (Fig. 30.4). The architecture is that of intersecting short fascicles (Fig. 30.5). The vasculature can range from inconspicuous to hemangiopericytoma-like, whereas the stromal component may be inconspicuous or may exhibit prominent myxoid change, hyalinization, or dystrophic calcification (Fig. 30.6). Prominent collagen fibrils, so-called “skeinoid” fibers, have been described in small bowel GISTs (Fig. 30.7).45,46

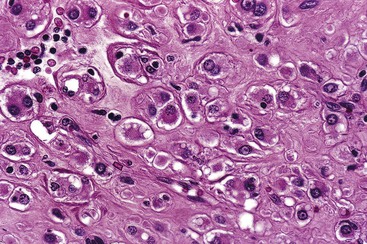

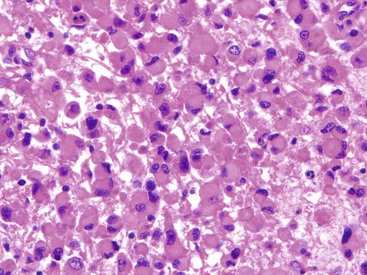

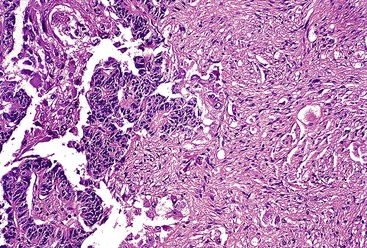

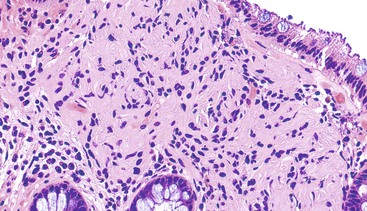

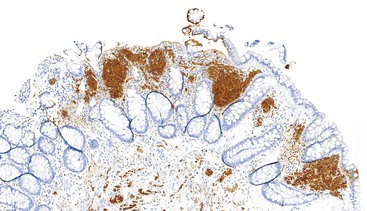

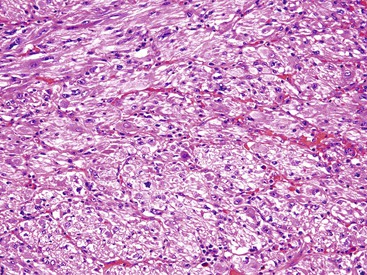

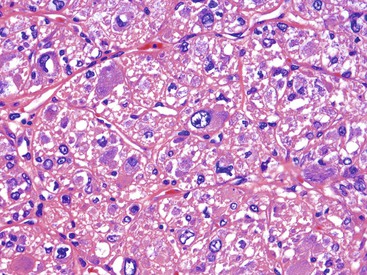

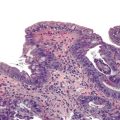

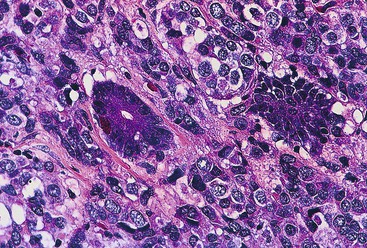

Epithelioid GISTs are composed predominantly of cells with either abundant eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm, typically arranged in nests and sheets. The nuclei are round with vesicular chromatin and variable nucleoli (Fig. 30.8). Scattered multinucleated giant cells, binucleated cells, or cells with bizarre nuclei may be present (Fig. 30.9).47 The stromal alterations may include hyalinization or myxoid change (Fig. 30.10). Confusion with other epithelioid malignancies can be problematic on endoscopic biopsies, especially when an epithelioid GIST involves the mucosa (Fig. 30.11).

Immunohistochemical Features

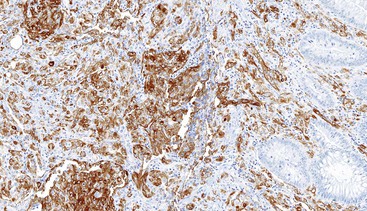

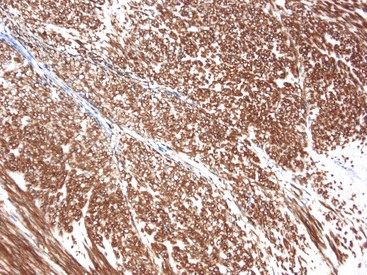

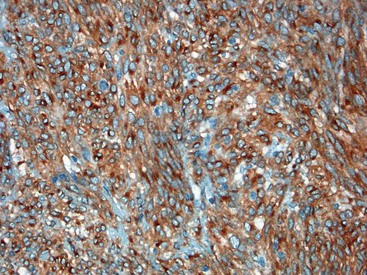

CD117 (KIT), the product of the KIT gene, is a sensitive marker of GISTs, irrespective of site; it is expressed in as many as 95% of GISTs.48 The pattern of immunoreactivity is typically diffuse and pancytoplasmic (Fig. 30.12), although membranous staining and a perinuclear dotlike immunoreactivity have been described (Fig. 30.13). Approximately 5% of GISTs do not react with antibodies to KIT49,50; often, these tumors belong to the subset of GISTs that contain a PDGFRA mutation.51 The KIT-negative tumors are often located within the stomach and have epithelioid morphology. CD34, a hematopoietic stem cell marker, is expressed in roughly 70% of GISTs.52,53 Approximately 20% to 30% of GISTs are positive for smooth muscle actin, 5% express some positivity for S100 protein, and 1% to 2% are positive for desmin or keratin.5,18,48

Gene expression profiling studies of GISTs have identified two additional immunostains that appear diagnostically useful. Discovered on GIST 1 (DOG1),54 also known as anoctamin 1 (ANO1), encodes a calcium-regulated chloride channel protein.55,56 The corresponding ANO1/DOG1 antibody appears to be immunoreactive with GISTs regardless of their KIT/PDGFRA mutational status57,58 and has a sensitivity similar to that of KIT (approximately 95%). However, DOG1 positivity has also been identified in a small subset of mesenchymal tumors, including leiomyomas and synovial sarcomas.59 Gene expression studies have shown protein kinase C-theta to be consistently overexpressed in GISTs,60,61 and the initial immunohistochemical studies have shown this protein to be sensitive and specific for the diagnosis of GIST.62

Molecular Findings

KIT and PDGFRA encode homologous transmembrane glycoproteins63,64 that contain an extracellular ligand-binding domain with five immunoglobulin-like loops that function in ligand binding and dimerization. The corresponding cytoplasmic domain is composed of a juxtamembrane domain and a tyrosine kinase domain; the juxtamembrane domain regulates KIT tyrosine kinase activity by inhibiting activity in the absence of KIT ligand.65 As mentioned previously, mutually exclusive mutations in KIT or PDGFRA have been identified in GISTs (as many as 80% and 10%, respectively).18–22 The identification of these mutations in small, incidentally identified GISTs confirms their role as drivers of early tumorigenesis.30,66 Although most of these mutations are somatic, germline mutations have been identified in rare families (see GIST Syndromes and Succinate Dehydrogenase–Deficient GISTs).67–72

Approximately 70% of the mutations involving KIT are identified at the juxtamembrane domain in exon 11, resulting in ligand-independent activation of tyrosine kinase activity and ultimately promoting proliferation and cell survival.65,73–75 The mutations cluster at either the 3′ or the 5′ end of the exon, with the mutation type frequently determining the clinical course. For example, internal tandem duplication mutations have been identified at the 3′ end of exon 11, and these patients typically have gastric GISTs that follow an indolent course.76 In comparison, an aggressive clinical course with a higher risk of recurrence and shorter survival time has been observed in GISTs harboring deletions involving exon 11.77–79 The second most common KIT mutation site, seen in approximately 10% of GISTs, has been identified within exon 9 (distal extracellular domain). Patients whose GISTs harbor this mutation commonly have small bowel involvement and a more clinically aggressive neoplasm.76 Mutations in exons 13 and 17 affect the tyrosine kinase domain of KIT and are seen in fewer than 5% of sporadic GISTS.80,81 The corresponding morphology is typically spindle cell with frequent involvement of the small bowel.82

The subset of GISTs that harbor a mutation in PDGFRA most commonly have a missense mutation in exon 18.83,84 GISTs containing this mutation almost always involve the stomach and have an epithelioid morphology.44,83,85 Less commonly, PDGFRA exon 14 and exon 12 mutations are seen; exon 14 mutations are also associated with epithelioid morphology, location within the stomach, and a favorable clinical course.83 In general, PDGFRA mutations are found within GISTs of the stomach and omentum, and these lesions typically have epithelioid morphology.44,85–87 A primary BRAF V600E mutation has been identified in a small subset of GISTs that lack either KIT or PDGFRA mutations.88–90

Differential Diagnosis

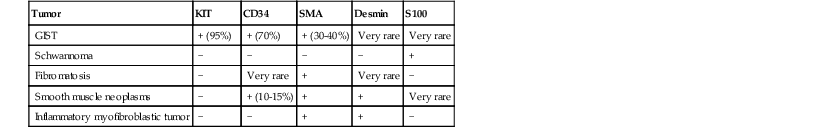

GISTs with a spindle cell morphology must be distinguished from other spindle cell proliferations of the GI tract, including smooth muscle neoplasms, nerve sheath tumors, inflammatory fibroid polyps, inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors (IMTs), and intraabdominal fibromatoses (desmoid tumors) (Table 30.2).

Table 30.2

Comparison of GIST Immunophenotype with Other Spindle Cell Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract

| Tumor | KIT | CD34 | SMA | Desmin | S100 |

| GIST | + (95%) | + (70%) | + (30-40%) | Very rare | Very rare |

| Schwannoma | − | − | − | − | + |

| Fibromatosis | − | Very rare | + | Very rare | − |

| Smooth muscle neoplasms | − | + (10-15%) | + | + | Very rare |

| Inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor | − | − | + | + | − |

GIST, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor; SMA, smooth muscle actin; −, absent; +, present.

Modified from Fletcher CD, Berman JJ, Corless C, et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:459-465.

Although smooth muscle tumors of the GI tract are much less common than GISTs, location is important because leiomyomas are more common than GISTs in the colon, rectum, and esophagus. GI leiomyomas are composed of spindle cells with cigar-shaped nuclei and eosinophilic fibrillar cytoplasm arranged in fascicles. Leiomyosarcomas of the GI tract are exceptionally rare and have cytologic pleomorphism and atypical mitotic figures, both of which are uncommonly seen in GISTs. The cells are strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for actin (smooth muscle actin and muscle-specific actin) and are often immunoreactive for desmin, but there is no expression of KIT.38,45

Nerve sheath tumors are also a consideration, including neurofibromas, schwannomas, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. GI schwannomas, the most common of these nerve sheath tumors, usually occur in the stomach. They are composed of bundles of spindle cells with focal atypia, often arranged in a microtrabecular growth pattern, and they are associated with a dense peripheral lymphoid infiltrate. They stain strongly for S100 protein and for glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and are negative for KIT. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors have rarely been described as arising within the GI tract; they resemble their counterparts in the peripheral soft tissues. In contrast to GISTs, these lesions do not express KIT and are variably immunoreactive for S100 protein.

Less commonly, inflammatory fibroid polyps (see Chapter 20) enter the differential diagnosis. They have been described throughout the GI tract,91 but they have a propensity for the stomach and ileum, where they a form an intramural mass. These lesions are composed of randomly distributed, spindle- and stellate-shaped cells associated with numerous blood vessels and inflammatory cells, especially eosinophils, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and mast cells. Frequently, there is a concentric whorling of the spindle cells in an onion-skin pattern around blood vessels. KIT highlights the scattered mast cells, whereas the spindle cells are negative for KIT. The spindle cells and vessels are immunoreactive for CD34, posing potential confusion with GISTs.92 Additionally, inflammatory fibroid polyps have been found to harbor gain-of-function mutations in PDGFRA within the same genomic hot spots as those identified within GISTs that lack an activating KIT mutation.93 Despite having similar activating mutations, inflammatory fibroid polyps behave in a benign fashion and are not thought to be related to GIST.

IMTs are most common in children and young adults and can arise as an intraabdominal mass involving the GI tract. The constituent cells have the light microscopic and immunohistochemical features of myofibroblasts, intermingled with inflammatory cells and collagen. The cells are KIT negative and frequently express anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) caused by rearrangements of the ALK gene on 2p23.94

Intraabdominal fibromatosis (desmoid tumor) is the most common primary tumor of the mesentery; it often originates from the gastrocolic ligament and omentum. Mesenteric fibromatosis is arranged in long, sweeping fascicles that have finger-like projections extending into the surrounding soft tissue. Scattered keloid-type collagen fibers may be present, as are dilated thin-walled vessels. The lesional spindled or stellate-shaped cells are cytologically bland and monotonous and are distributed evenly within a collagenous or myxoid stroma. By immunohistochemistry, the lesional cells are immunoreactive for vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and muscle-specific actin, and they frequently have β-catenin nuclear immunoreactivity.95 These lesions are typically KIT negative, although one group has reported KIT immunoreactivity in these tumors.96

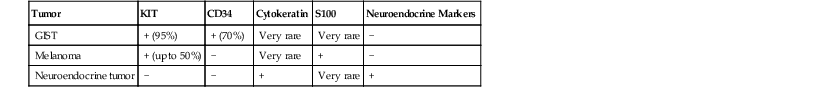

GISTs with epithelioid features raise a broad differential diagnosis that includes melanoma, neuroendocrine tumors, and carcinoma; judicious use of immunohistochemical stains is warranted in this setting given the histologic overlap (Table 30.3). Because expression of KIT has been identified within a subset of melanomas,97–99 excluding the possibility of melanoma by performing a panel of melanocytic markers including S100 protein, human melanoma black (HMB)-45, or melan-A is warranted. Rare examples of epithelioid GISTs show focal cytokeratin immunoreactivity, so the coexpression of CD34 and DOG1 with KIT (or without KIT in epithelioid GISTs containing PDGFRA mutations) is essential to avoid misdiagnosis of such cases as carcinoma.

Table 30.3

Comparison of GIST Immunophenotype with Other Epithelioid Tumors of the Gastrointestinal Tract

| Tumor | KIT | CD34 | Cytokeratin | S100 | Neuroendocrine Markers |

| GIST | + (95%) | + (70%) | Very rare | Very rare | − |

| Melanoma | + (up to 50%) | − | Very rare | + | − |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | − | − | + | Very rare | + |

GIST, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor; −, absent; +, present.

Overall, nuclear pleomorphism is unusual in GISTs, and the finding of marked cytologic pleomorphism could suggest sarcoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, or the very rare dedifferentiated GIST. This dedifferentiation is akin to dedifferentiation in other sarcomas, wherein a transition from a morphologically recognizable low-grade tumor to an anaplastic or pleomorphic morphology is appreciated (Fig. 30.14). In the setting of GIST with dedifferentiation, the morphology changes, and the immunophenotype undergoes a transition as well, with loss of KIT immunoreactivity within the anaplastic cells.100 Dedifferentation has been described both as a de novo event and as occurring after treatment with the selective tryosine kinase inhibitor imatinib mesylate (ST1571 or Gleevec; Novartis Pharmaceuticals, East Hanover, N.J.).100

Prognosis and Treatment

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have played a pivotal role in the management of GISTs, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved two targeted therapies. Imatinib mesylate is a selective tryosine kinase inhibitor that targets KIT and PDGFRA. Sunitinib malate (SU11248 or Sutent; Pfizer, New York, N.Y.) targets several receptors including those for KIT, PDGFRA, and vascular endothelial growth factor.101–103 The original indication for imatinib was for the treatment of metastatic or unresectable GISTs, with patients showing clinical responses in as many as 80% of cases104; current FDA-approved labeling includes use in the adjuvant setting after complete gross resection of GISTs.105 Sunitinib is approved for patients who do not tolerate imatinib or who have tumor progression on imatinib therapy. Tumor genotype has been shown to correlate with response to these drugs. For example, tumors with an exon 11 KIT mutation have shown the best imatinib response rates, whereas tumors without a KIT mutation and those with a PDGFRA D842V mutation are less likely to have a favorable or a sustained response to imatinib.51,106 Other studies suggest that patients with an exon 9 KIT mutation benefit from a higher dose of this drug.107,108 Approximately 50% of GIST patients being treated with imatinib will acquire a secondary mutation that confers tumor resistance to imatinib,109–112 and in such cases, sunitinib is approved as a second-line therapy. The most common secondary KIT mutations that escape imatinib are KIT V654A and KIT T670I, both of which are sensitive to sunitinib. Regorafenib (Stivarga; Bayer HealthCare, Whippany, N.J.) has been approved by the FDA as third-line therapy for patients whose disease progresses on sunitinib.

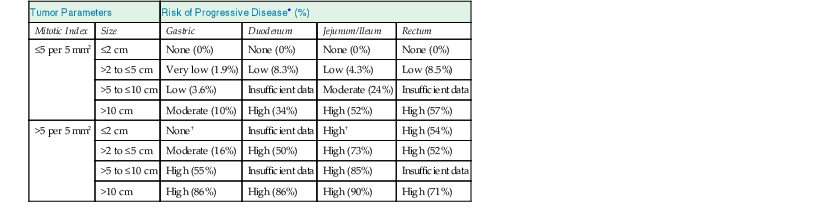

GISTs are risk stratified based on mitotic rate, size, and anatomic location; these features define the Miettinen criteria for risk stratification (Table 30.4),23 which establish a risk of progressive disease, defined as either metastatic disease or tumor-related death. The criteria are based on large studies by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) that evaluated how the clinicopathologic features of GISTs within different sites (gastric, small intestinal, duodenal, and rectal locations) affected prognosis in the pre-imatinib era.38,43,45,46 To assign an accurate risk of progressive disease, a precise gross tumor measurement with a thorough mitotic count should be performed, evaluating a total area of 5 mm2. For modern wide-field microscopes with wide-field eyepieces, the mitotic count correlating with the total area of 5 mm2 is obtained from 20 high-power fields (HPFs).5

Table 30.4

Risk Stratification of Primary GIST by Mitotic Index, Size, and Anatomic Site

| Tumor Parameters | Risk of Progressive Disease* (%) | ||||

| Mitotic Index | Size | Gastric | Duodenum | Jejunum/Ileum | Rectum |

| ≤5 per 5 mm2 | ≤2 cm | None (0%) | None (0%) | None (0%) | None (0%) |

| >2 to ≤5 cm | Very low (1.9%) | Low (8.3%) | Low (4.3%) | Low (8.5%) | |

| >5 to ≤10 cm | Low (3.6%) | Insufficient data | Moderate (24%) | Insufficient data | |

| >10 cm | Moderate (10%) | High (34%) | High (52%) | High (57%) | |

| >5 per 5 mm2 | ≤2 cm | None† | Insufficient data | High† | High (54%) |

| >2 to ≤5 cm | Moderate (16%) | High (50%) | High (73%) | High (52%) | |

| >5 to ≤10 cm | High (55%) | Insufficient data | High (85%) | Insufficient data | |

| >10 cm | High (86%) | High (86%) | High (90%) | High (71%) | |

* Based on long-term follow-up of 1055 gastric, 629 small intestinal, 144 duodenal, and 111 rectal GISTs. Progression is defined as metastasis or tumor-related death.

† Denotes small numbers of cases.

GIST, Gastrointestinal stromal tumor; HPF, high-power field.

Data from references 23, 38, 43, 45, and 46.

Other factors that have been reported to be associated with poor outcome include tumor necrosis, mucosal invasion, and ulceration.43,113,114 Tumor rupture, either spontaneous or at the time of surgery, increases the risk of recurrence with intraabdominal seeding.115,116 Patients whose complete resection is complicated by tumor rupture have a significantly shortened survival time, compared with patients with complete resection without tumor rupture.116–118

GIST Syndromes and Succinate Dehydrogenase–Deficient GISTs

Although most GISTs are sporadic, almost 5% are associated with a tumor syndrome, including familial GIST syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), the Carney triad, and Carney-Stratakis syndrome.

Familial GISTs arise from germline mutations in exons 8, 11, and 13 of KIT and in exon 12 of PDGFRA, identical to the mutations identified in sporadic GISTs.69,70,119–124 GISTs will develop in almost all patients who harbor these germline mutations, typically within the stomach and small bowel. These lesions most commonly develop in middle-aged patients, but they have been documented in patients as young as 18 years. Other clinical manifestations of KIT activation, such as mastocytosis (urticaria pigmentosa) and hyperpigmented macules on the skin of the perineum, axilla, hands, and face, may also be found in these patients, as well as a background of diffuse ICC hyperplasia in the bowel wall.69,72 This latter finding raises the possibility of a hyperplasia to neoplasia sequence, with additional clonal genetic alterations needed to progress from ICC hyperplasia to GIST.125

GISTs arising in patients with NF1 have been recognized for some time and may even be the most common GI tract tumor associated with NF1.24 As estimated from a series of duodenal GISTs reported by the AFIP, patients with NF1 have an increased risk for GIST of as high as 180-fold compared with the general population.45 Most NF1-associated tumors arise in the small bowel, often in a multifocal fashion.126,127 Distinguishing patients with NF1 and multiple GISTs from patients with sporadic GIST and multiple metastatic nodules is of major clinical significance. Most NF1-associated GISTs are relatively small, are mitotically inactive, and follow an indolent course. Therefore, the index of suspicion for NF1 should be high when one encounters multiple small GISTs, particularly in the small bowel. Diffuse ICC hyperplasia is often seen in the myenteric plexus adjacent to these tumors. The pathogenesis of NF1-associated GISTs appears to be different from that of sporadic GISTs because several studies have shown a very low frequency of associated KIT or PDGFRA mutations in these tumors.126,128–131

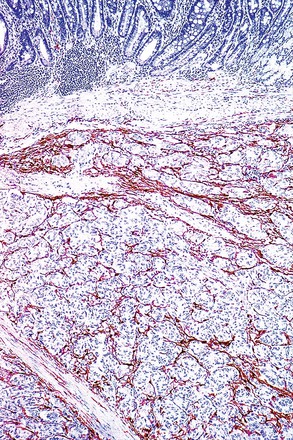

The identification of GIST arising in the setting of a germline mutation in the SDH complex family132 has led to the recognition of a distinctive group of SDH-deficient GISTs that are found in the stomach and share histologic, immunohistochemical, and clinical similarities. These GISTs arise in the setting of Carney-Stratakis syndrome, Carney triad, pediatric GIST, or “pediatric-type” GISTs in adults.133–135 They have a multinodular or plexiform growth with lobules of tumor separated by bands of smooth muscle, are hypercellular, and have epithelioid cytomorphology.133–136 In contrast to conventional GISTs, which show granular cytoplasmic staining for succinate dehydrogenase subunit B (SDHB), GISTs arising in these settings show a loss of immunohistochemical staining for SDHB.134 Clinically, these tumors metastasize to lymph nodes and are insensitive to imatinib mesylate; however, despite recurrences and distant metastases, they typically follow a more indolent clinical course.40,133,136,137

Carney-Stratakis syndrome is characterized by paraganglioma and gastric GISTs.136 It has been shown to result from a germline mutation in one of the SDH complex subunit genes and is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner.132,138,139 GISTs arising in this setting lack KIT and PDGFRA mutations.139

Carney triad, which includes epithelioid gastric GISTs, paraganglioma, and pulmonary chondroma, occurs exclusively in the stomach and usually arises in much younger patients with a striking female predilection (approximately 85%).136,140 Although mutations in KIT and PDGFRA have not been identified so far in this subset of GISTs, they typically stain with KIT.40,141 Recent literature suggests that GISTs in the setting of Carney triad are quite different from sporadic GISTs.40

GISTs may arise in children, albeit rarely, accounting for fewer than 1% of all GISTs.41 In the pediatric population, GISTs predominate in girls, are usually located in the stomach, and are frequently multifocal with epithelioid or mixed morphology.142 These lesions often metastasize to lymph nodes, and although they stain with KIT, they often lack mutations in KIT and PDGFRA; approximately 50% harbor mutations in SDH complex subunit genes.41,42,143 Approximately 3% of adults with GISTs have so-called “pediatric-type” GISTs, which are SDH-deficient; this subtype accounts for roughly 7% of gastric GISTs in adults. These tumors have histomorphology identical to that seen in pediatric patients and a similar clinical course, with nodal metastases, imatinib resistance, and an overall indolent course.142,144

Tumors of Neural Origin

Schwannoma

Clinical Features

Schwannomas are thought to arise from the myenteric plexi and are most commonly encountered in the stomach,145 followed by the colon and rectum.146 These lesions have been rarely described in the esophagus or small intestine.147–150 Schwannomas have been documented in patients as young as 18 years,146 but they arise most commonly during middle to late adulthood, with a peak in the sixth decade.146,148,150,151 The largest series evaluating gastric schwannomas documented a female predominance, with a 1 : 4 male-to-female ratio.151 Schwannomas typically involve the muscularis propria and submucosa, with frequent ulceration of the overlying mucosa. Those arising in the stomach are usually a mural mass, whereas schwannomas in the colon and rectum often manifest as ulcerated polypoid lesions.146 The presenting clinical symptoms are typically specific to site. Schwannomas arising in the colon and rectum frequently manifest with rectal bleeding, abdominal pain, and colonic obstruction,146 whereas those arising in the stomach manifest with gastric discomfort and bleeding.151 That said, it is not unusual for gastric schwannomas to be identified incidentally during other procedures.151

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

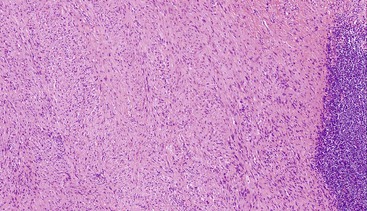

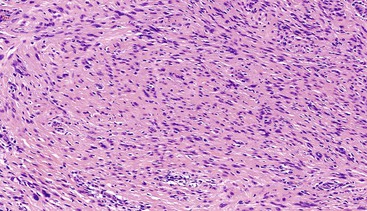

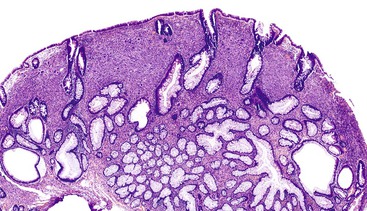

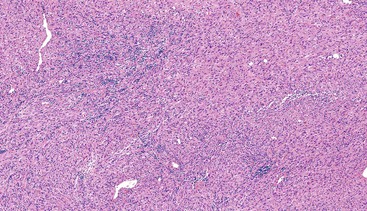

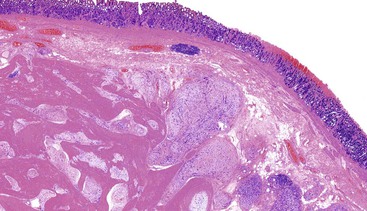

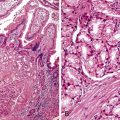

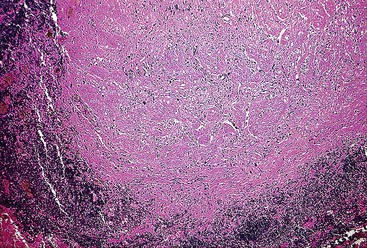

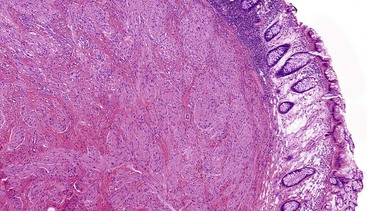

Schwannomas are grossly well circumscribed, round or ovoid mural lesions that are devoid of a true capsule. Grossly, the lesions are homogenous and firm with a tan to yellow cut surface without areas of cystic change or necrosis. Histologically, GI schwannomas are quite different from schwannomas of the central nervous system and peripheral soft tissue. The nuclear palisading, Verocay bodies, and hyalinized vessels typically seen in peripheral schwannomas are essentially absent in GI schwannomas. Also, unlike their soft tissue counterparts, GI schwannomas have a discontinuous cuff of lymphoid cells, often with germinal center formation at the periphery of the lesion (Fig. 30.15). The cellularity of these lesions varies in different portions of the tumor because of the amount of collagenous or myxoid stroma present. Some areas may be highly cellular and contain abortive fascicles or whorls (Fig. 30.16); other, less cellular areas may have a prominent hyalinized or myxoid stroma imparting a microtrabecular pattern. Scattered lymphocytes and plasma cells are often found within the tumor. The spindle cells composing the lesions have elongated, hyperchromatic nuclei with tapered ends, occasional intranuclear inclusions, and an inconspicuous nucleolus (Fig. 30.17). Scattered cells with nuclear atypia may be present, but mitotic activity is usually low (<5 mitoses per 50 HPFs); rarely, mitotic activity can be greater than 10 per 50 HPFs.151 Atypical mitotic figures should not be identified. Although the lesion is circumscribed, it can infiltrate the muscularis mucosae and entrap epithelium.

Although GI schwannomas are predominantly spindled, rare cases of epithelioid schwannoma have been described with the cells arranged in cords, sheets, and even a pseudoglandular pattern.146 Another rare histologic variant of schwannoma described within the GI tract is the microcystic/reticular schwannoma.152 This variant is different from the conventional GI schwannoma in that the usual peripheral lymphoid cuff is lacking and the lesions are composed of anastomosing strands of tumor cells with either round, oval, or tapered nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm set within a myxoid, fibrillary, or collagenous stroma.152

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Similar to their soft tissue counterparts, GI schwannomas are strongly and diffusely immunoreactive for S100 protein and GFAP, and they can show focal CD34 staining. These lesions are consistently negative for KIT, cytokeratins, and muscle markers.

Not only are GI schwannomas histologically different from their conventional soft tissue counterparts, but they are also different molecularly. The somatic NF2 gene mutations that are common in sporadic soft tissue schwannomas are unusual events in GI schwannomas.153 GI schwannomas lack an association with neurofibromatosis, with only one reported instance of identification of a gastric schwannoma in a patient with NF1.129,147,154 In contrast to GIST, which falls in the differential diagnosis, GI schwannomas lack KIT and PDGFRA mutations.

Gangliocytic Paraganglioma

Clinical Features

The term gangliocytic paraganglioma” was coined by Kepes and Zacharias155 in 1971 when they recognized features of both paraganglioma and ganglioneuroma within the same lesion. Gangliocytic paraganglioma is a rare tumor that most commonly arises in the second portion of the duodenum.156 However, examples have been described in the esophagus, stomach, appendix, pancreas, nasopharynx, bronchus, and lung.157–163 Common presenting symptoms include GI bleeding, abdominal pain, and obstruction. Rarely, cases have been identified incidentally at endoscopy or even at autopsy.164

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

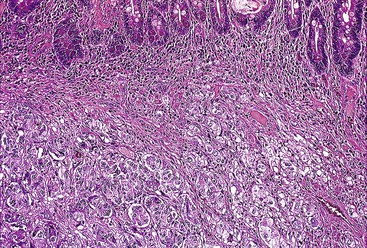

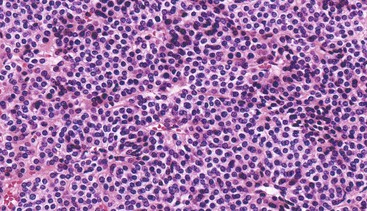

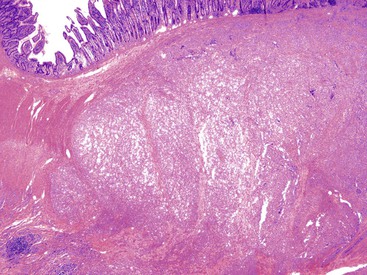

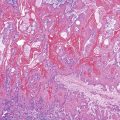

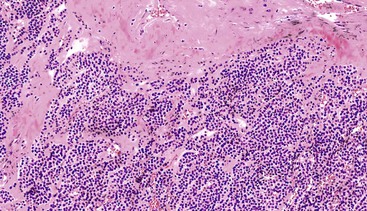

Gangliocytic paraganglioma is typically a circumscribed lesion centered on the submucosa and may extend into the muscularis propria. The lesion is a triphasic tumor composed of nests of epithelioid neuroendocrine cells resembling a paraganglioma, ganglion cells or ganglion-like cells, and spindle-shaped Schwann cells with neuromatous stroma. The components are haphazardly arranged, and one component may predominate. The neuroendocrine component have a ribbon-like or trabecular growth pattern (Figs. 30.18 and 30.19), whereas the ganglion cells have variable degrees of differentiation (Fig. 30.20). The neuromatous stroma may have a fascicular architecture.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Immunohistochemically, a variety of antigens, including CAM 5.2, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, serotonin, synaptophysin, and sometimes chromogranin, may be expressed in the neuroendocrine component. The ganglion cells express NSE, synaptophysin, neurofilament protein, and variable chromogranin. The Schwann cells and neuromatous stroma are positive for expression of neurofilament, S100 protein, and NSE. S100 protein highlights a sustentacular network surrounding the neuroendocrine cell nests (Fig. 30.21). To date, no recurrent molecular alterations have been described in gangliocytic paraganglioma.

Treatment and Prognosis

Most gangliocytic paragangliomas behave in a benign fashion, and local resection typically provides adequate treatment. However, rare cases with regional nodal metastases165–168 or distant metastases have been reported.161,169 It has been suggested that prominent nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic activity, and an infiltrative margin raise concern for aggressive behavior,170 although many of the cases described in the literature with nodal involvement or more distant disease lacked these features. More importantly, the involvement of lymph nodes is not necessarily predictive of an adverse outcome, because patients with nodal disease were alive and well as long as 91 months after surgical resection.158

Ganglioneuroma and Ganglioneuromatosis

Clinical Features

Ganglioneuromas are benign Schwann cell and ganglion cell proliferative lesions that may occur within the GI tract. These lesions may manifest as mucosa-based polyps that arise as sporadic solitary polypoid ganglioneuromas,171 as a ganglioneuromatous polyposis with multiple polyps involving the lower and upper GI tract (e.g., in the setting of Cowden syndrome),172–175 or as diffuse ganglioneuromatosis that may involve the deeper aspects of the bowel wall (e.g., in multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIb [MEN IIb])176–179 and NF1).178,180–182 Solitary polypoid ganglioneuroma is usually identified incidentally at the time of colonoscopy; accordingly, it is seen most often in the middle-aged to older adult population who are undergoing screening colonoscopy. In the setting of Cowden syndrome, multiple polypoid ganglioneuromas are seen in addition to several other polyp types, including hyperplastic polyps, adenomas, inflammatory polyps, and hamartomatous polyps.172,174,175 Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis may occur across a wide age range, typically with vague symptoms including abdominal pain, constipation, or diarrhea.177 Given the multiple cancer risks associated with Cowden syndrome, MEN IIb and NF1, it is prudent to mention the association of these syndromes when diagnosing a ganglioneuroma or ganglioneuromatosis, so that appropriate genetic testing may be initiated if clinically warranted.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

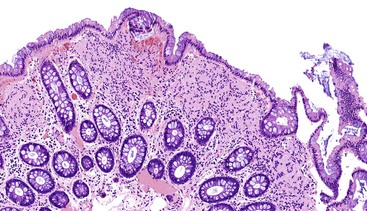

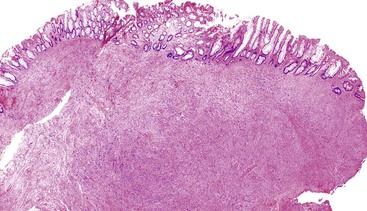

Solitary polypoid ganglioneuromas are usually sessile polyps measuring less than 2 cm.180 Ganglioneuromatous polyposis has a varied extent of involvement; in some cases polyps are few and small, whereas other examples have shown extensive mucosal involvement. The sporadic and syndromic polypoid ganglioneuromas are histologically similar and contain a hypercellular lamina propria composed of cytologically bland, spindle-shaped cells with schwannian features (Fig. 30.22). Ganglion cells may be arranged in clusters but are often isolated and can be difficult to identify (Fig. 30.23). The glandular epithelium is often splayed apart by the expanded lamina propria, resulting in a distorted appearance at low magnification.

Diffuse ganglioneuromatosis may manifest as a bowel wall thickening or a more discrete mass.177,178,180 Histologically, the submucosal or myenteric plexi may be involved and may show a nodular expansion by Schwann cells and ganglion cells that typically extend insidiously into the adjacent submucosa or muscularis propria. Involvement of the mucosa is seen more commonly in NF1.181

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

The ganglion cells are immunoreactive for NSE, and neurofilament protein highlights their processes; the Schwann cells are immunoreactive for S100 protein.

As mentioned earlier, these lesions raise the possibility of MEN IIb, NF1, or Cowden syndrome with germline mutations identified in RET, NF1, and PTEN, respectively. To date, no recurrent molecular alteration has been identified in sporadic polypoid ganglioneuromas.

Treatment and Prognosis

These lesions are benign, and management is ultimately determined based on whether a germline mutation is identified. Given the involvement of the bowel wall by a diffuse ganglioneuromatosis, resection of the affected segment of bowel may be required for symptom management.

Mucosal Perineurioma

Clinical Features and Background

The mucosal polypoid lesion that is now referred to as a mucosal perineurioma183–185 represents what was described in the earlier literature as a “benign fibroblastic polyp.”186,187 Mucosal perineuriomas are benign nerve sheath tumors composed of perineurial cells and are commonly identified incidentally at colonoscopy.184 These small, sessile lesions appear to be female predominant and have a predilection for the rectosigmoid.183,184,187

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

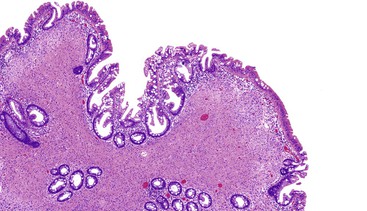

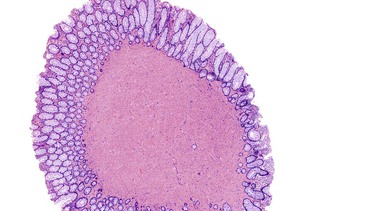

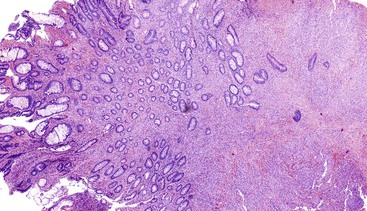

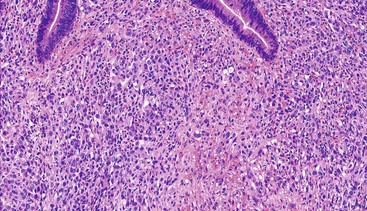

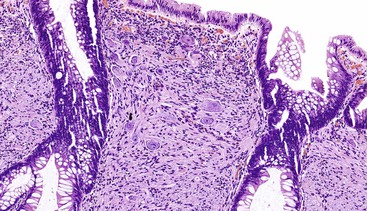

Mucosal perineuriomas average 4 mm in diameter and are predominately solitary lesions composed of bland spindle cells that expand the lamina propria and splay the crypts, often with a whorled growth pattern around crypts. The proliferation is centered in the mucosa but may extend into the superficial submucosa. The spindle cell nuclei have fine chromatin, lack nucleoli, and have eosinophilic cytoplasm. In most cases, the associated colonic epithelium has a serrated architecture akin to a hyperplastic polyp or a sessile serrated polyp (Figs. 30.24 and 30.25).183,185,186

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Mucosal perineuriomas express perineurial markers, including epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), GLUT1, claudin-1, and vimentin, although EMA staining may be very weak. Mucosal perineuriomas are negative for KIT, S100 protein, smooth muscle actin, and desmin.

The serrated epithelium in these lesions has been shown to harbor the V600E BRAF mutation185,188 typical of sessile serrated polyps and hyperplastic polyps. Based on this molecular finding and the frequent association of perineuriomatous stroma within serrated polyps, some authors have suggested that the stroma represents a reactive phenomenon driven by the serrated epithelium.

Treatment and Prognosis

Mucosal perineuriomas are benign, and recurrences have not been documented.

Mucosal Schwann Cell Hamartoma

Clinical Features

Mucosal Schwann cell hamartomas are sporadic polypoid lesions that have been recognized in the colon.189 They are asymptomatic and are usually identified on screening colonoscopy, predominantly within the sigmoid and rectum.189 They are most commonly detected in middle-aged to elderly patients, the same group that tend to undergo colonoscopy. There is a female predominance.189–191

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

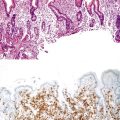

Mucosal Schwann cell hamartomas have a mean size of 2.5 mm and typically are described as small sessile polyps.189 Histologically, the polyps are composed of an ill-defined proliferation of spindle cells within the lamina propria that entrap colonic crypts and have an irregular border with the adjacent uninvolved lamina propria (Fig. 30.26). The lesion is composed of uniform, bland spindle cells with elongated or wavy nuclei with fine chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, eosinophilic cytoplasm, and indistinct cell borders (Fig. 30.27). Cytologic atypia and mitotic activity have not been described.

Immunohistochemistry

By immunohistochemistry, the lesional cells show strong and diffuse reactivity for S100 protein (Fig. 30.28). Other markers that are typically negative include GFAP, EMA, CD34, smooth muscle actin, and KIT.189

Treatment and Prognosis

Mucosal Schwann cell hamartoma was first fully described in 2009 by Gibson and Hornick189; limited studies with clinical outcome are available in the literature. However, the lesion appears to be benign, and recurrences have not been documented. To date, these lesions have not been associated with specific inherited syndromes (NF1, MEN IIb, or PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome).

Granular Cell Tumor

Clinical Features

Most granular cell tumors of the gut arise within the esophagus, but they may arise anywhere throughout the GI tract.192 Occasionally, one encounters multiple lesions arising in different portions of the GI tract, either metachronously or synchronously.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

Granular cell tumors are predominantly located in the submucosa but may involve the muscularis propria, the muscularis mucosae, and the mucosa. The lesional cells are either plump and epithelioid or spindled with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (Fig. 30.29) containing numerous periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive, diastase-resistant phagolysosomes. The nuclei may be small and hyperchromatic or large with open chromatin. The cells are typically arranged in nests with intervening fibrous tissue or broad sheets (Fig. 30.30).

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Granular cell tumors are uniformly immunoreactive for S100 protein (Fig. 30.31) and NSE. Because of the presence of numerous lysosomes, the panmacrophage marker CD68 is typically immunoreactive.193,194

Treatment and Prognosis

Essentially, granular cell tumors behave in a clinically benign fashion, and local excision is considered adequate therapy. However, rare examples of malignant granular cell tumor have been described in the soft tissues, and it may be fair to extrapolate these findings to granular cell tumors within other sites (Fig. 30.32). The largest series of malignant granular cell tumors was reported by Fanburg-Smith and colleagues, who evaluated six histologic variables that they considered potentially indicative of malignancy: necrosis, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, increased mitotic rate (>2 mitoses per 10 HPFs at 200× magnification), spindling of tumor cells, a high nucleus-to-cytoplasm (N : C) ratio, and pleomorphism. Multivariate analysis showed that spindling, increased N : C ratio, and vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli were the features most closely related to the classification as malignant.195

Tumors of Smooth Muscle Origin

Smooth muscle tumors of the GI tract arise from the muscularis mucosae or the muscularis propria. They are characterized by positive staining for a variety of muscle markers, including actin and desmin, and a lack of immunoreactivity for KIT.

Leiomyoma

Clinical Features

Leiomyomas that come to clinical attention occur predominately in the colon, rectum, esophagus, and, rarely, stomach and small intestine.38,45 Most are discovered incidentally during evaluations for other processes.196 Approximately 80% of GI leiomyomas are identified in the colon and rectum as small (<1 cm) nodules that arise from the muscularis mucosae, most commonly in middle-aged to elderly men.197 Some are attached to the external rectal wall and resemble uterine leiomyomas; estrogen and progesterone receptors may be positive in this subgroup of leiomyomas.197

Approximately 10% of GI leiomyomas arise in the esophagus, developing from the muscularis propria and forming intramural masses or, less commonly, polypoid masses.25 Esophageal leiomyomas arise typically in young men (median age, 30 to 35 years) and in the lower one third of the esophagus, often with dysphagia as the presenting symptom.25 Rarely, leiomyomas are found throughout the esophagus, where the muscularis propria is essentially replaced by a nodular smooth muscle proliferation, a condition referred to as esophageal leiomyomatosis.198,199 This condition is most commonly seen in children and adolescents.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

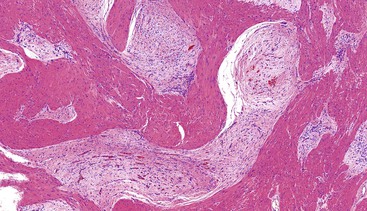

Colorectal leiomyomas are described as small polyps, typically with a gross or endoscopically described pedunculated appearance.197 Esophageal leiomyomas are larger lesions given their mural location, with a median size of 5 cm.25 Histologically, GI leiomyomas, regardless of their site of origin, are characterized by a proliferation of bland, spindle-shaped cells with elongate, cigar-shaped nuclei and brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm. The lesions are of low or moderate cellularity and have a fascicular architecture (Figs. 30.33 and 30.34). Mitotic activity is minimal (0 to 1 per 50 HPFs).

Treatment and Prognosis

Leiomyomas have a benign behavior, and those in the colon and rectum are usually excised easily by endoscopic polypectomy.197 Rarely, they develop as intramural masses in the rectum and require more invasive treatment. For esophageal leiomyomas, resection via enucleation has been recommended for symptomatic patients, and asymptomatic patients may be observed.

Leiomyosarcoma

Clinical Features

Leiomyosarcomas of the GI tract are rare and have not been well studied. It is now known that the lesions described as “leiomyosarcomas of the gastrointestinal tract” in previously published studies were in fact GISTs. Similar to GISTs, these tumors typically occur in older patients.200 Although they may occur anywhere within the GI tract, they have been described most commonly in the small intestine and colon.38,45,196,200 Depending on tumor location, patients may have symptoms ranging from dysphagia, to GI bleeding with anemia, to obstruction.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

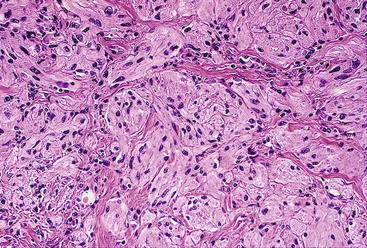

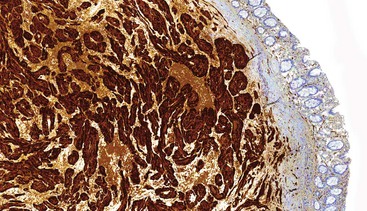

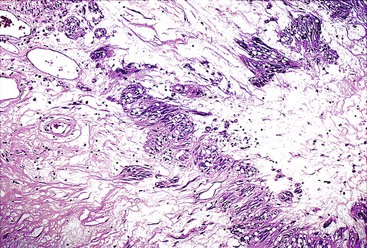

GI leiomyosarcomas have a variable gross presentation as either large lesions that involve the full thickness of the bowel wall or ulcerated polypoid masses that project into the luminal aspect of the GI tract.38,45 Leiomyosarcomas of the GI tract are indistinguishable histologically from leiomyosarcomas of other sites. They are composed of spindle cells with elongated nuclei and eosinophilic fibrillary cytoplasm arranged in fascicles (Fig. 30.35). Rather prominent atypia with enlarged, hyperchromatic and pleomorphic nuclei is seen, with brisk mitotic activity (Fig. 30.36). Areas of necrosis are common.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Immunohistochemistry allows for the recognition of leiomyosarcomas as true smooth muscle tumors: These lesions are strongly immunoreactive for smooth muscle actin, with variable expression of caldesmon and desmin. Focal immunoreactivity for CD34 and EMA has been described.25 S100 protein, DOG1, and KIT are consistently negative.

Treatment and Prognosis

Based on the limited data that exist, GI leiomyosarcomas are locally aggressive; they metastasize frequently to intraabdominal surfaces and the liver, and rarely to lymph nodes.201 Given the rarity of these lesions, minimal criteria for malignancy have not been established. However, malignant features extrapolated from retroperitoneal and abdominal lesions considered to be leiomyosarcomas include a minimum mitotic rate of 1 to 4 per 10 HPFs, some degree of nuclear atypia, and coagulative necrosis.202,203

Smooth Muscle Tumors of Uncertain Malignant Potential

As stated previously, identification of atypia within a smooth muscle tumor should raise concern for malignancy. However, some cases that have been well sampled and contain only focal atypia without the presence of mitotic activity are not classifiable as leiomyosarcoma. In such instances, the designation “smooth muscle tumor of uncertain malignant potential” may be most appropriate.

Fibroblastic Tumors

Mesenteric Fibromatosis

Clinical Features

The intraabdominal fibromatoses are a group of closely related lesions that frequently involve the GI tract. This category includes both pelvic and mesenteric fibromatoses, including those associated with familial adenomatosis polyposis (FAP). Fibromatosis is the most common primary tumor of the mesentery and accounts for approximately 8% of all fibromatoses. Most commonly, these tumors arise in the small bowel mesentery, but some originate from the ileocolic mesentery, gastrocolic ligament, retroperitoneum, or omentum. Identifying a mesenteric fibromatosis in a child should heighten clinical concern for the possibility of FAP.204,205 Most patients have an asymptomatic abdominal mass at presentation, but some have GI bleeding or an acute abdomen secondary to bowel obstruction or perforation.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

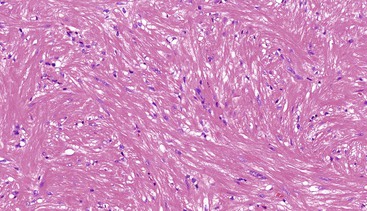

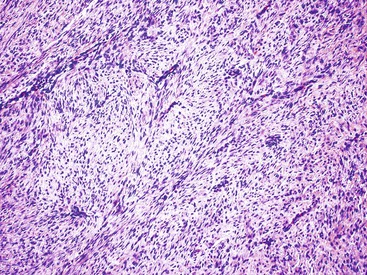

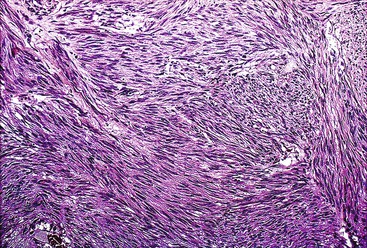

Most mesenteric fibromatoses are large (10 cm or larger) at the time of excision. Although grossly well circumscribed, these lesions typically infiltrate into the surrounding soft tissues, including the bowel wall. Histologically, mesenteric fibromatoses are composed of cytologically bland, spindle- or stellate-shaped cells that are evenly deposited in a collagenous or sometimes myxoid stroma. These cells are arranged in long, sweeping fascicles. Scattered keloid-type collagen fibers may be present, as may dilated, thin-walled vessels (Figs. 30.37 and 30.38).

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Immunohistochemically, fibromatoses frequently express nuclear β-catenin and smooth muscle actin but overall are negative for KIT, DOG1, and desmin.57,59 The lesions that arise in the setting of FAP are caused by germline mutations in APC, whereas 52% to 89% of sporadic cases have been shown to contain somatic mutations in CTNNB1 (which encodes β-catenin)206–209 or, rarely, somatic mutations in APC.210 Either mutation can lead to the abnormal intranuclear accumulation of β-catenin and is thought to activate the downstream genes that result in tumor formation.

Treatment and Prognosis

Similar to fibromatoses elsewhere, intraabdominal fibromatoses have high rates of local recurrence, often seemingly not related to margin status. Radiotherapy is part of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) treatment algorithms, as are varied systemic therapies including nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, tamoxifen, methotrexate, and doxorubicin-based chemotherapy.

Inflammatory Myofibroblastic Tumor

Clinical Features

IMT is a distinctive lesion that often arises in an intraabdominal location in children and young adults, with an intermediate biologic potential. Although IMTs have been reported in virtually every anatomic location, the most common extrapulmonary sites are the mesentery and omentum.211 The median patient age at diagnosis is 43 years, although IMT has been identified in patients as young as 9 months.212 The lesions have been described throughout the GI tract, with the stomach, small intestine, and colon most commonly involved.212 Patients with intraabdominal IMTs often have abdominal pain or an abdominal mass, occasionally with signs and symptoms of GI tract obstruction. Some patients also have prominent systemic manifestations, including fever, night sweats, weight loss, and malaise.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

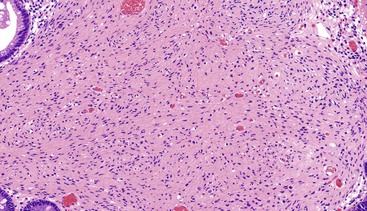

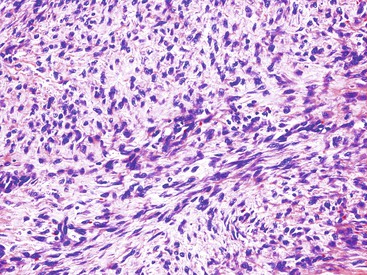

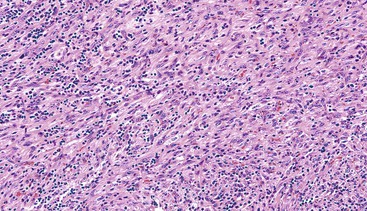

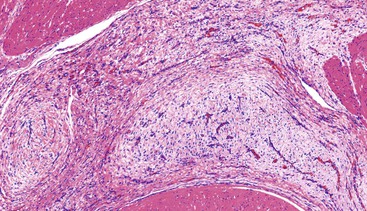

Grossly, most IMTs are lobular or multinodular with a rubbery cut surface; sometimes the presence of calcifications provides a gritty sensation when the lesion is cut. Although most are solitary lesions, multiple nodules restricted to the same anatomic location are found in as many as one third of cases.211 Histologically, a variety of patterns may be seen, either in the same tumor or in different tumors. Some are composed of cytologically bland, spindle- or stellate-shaped cells arranged in a variably collagenous or myxoid stroma with scattered inflammatory cells, closely resembling nodular fasciitis. Others are composed of a compact proliferation of spindle cells arranged in a fascicular growth pattern (Figs. 30.39 and 30.40). Other foci may be sparsely cellular, with cytologically bland cells deposited in a sclerotic stroma. A lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate is often conspicuous, and small areas of calcification or metaplastic bone may also be observed.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Immunohistochemically, the neoplastic cells stain for vimentin and variably with myoid markers including smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and desmin.213 Focal cytokeratin immunoreactivity may be found in up to one third of cases. Between 35% and 60% of IMTs stain for ALK protein, because some (but not all) IMTs harbor clonal cytogenetic aberrations of the ALK gene, located on 2p23.214 IMTs can be confused with inflammatory fibroid polyps, a benign lesion that most often occurs in the stomach and ileum as a solitary submucosal polyp (see Chapter 20).

Treatment and Prognosis

Although most of these tumors act in a clinically benign fashion, it is clear that some tumors in this location have a propensity for more aggressive behavior than their extraabdominal counterparts, with recurrence rates of 23% to 37%.211,213 A small minority of patients develop metastatic disease, usually to the lung and brain.213

Vascular Tumors

Hemangiomas and Other Benign Vascular Proliferations

Hemangiomas, lymphangiomas, and other benign vascular malformations are relatively common throughout the GI tract and resemble their counterparts in the peripheral soft tissues. Some are composed of large, cavernous vascular channels, and others contain lobules of small, capillary-sized vessels. These vascular proliferations, particularly lymphangiomas and benign vascular malformations (angiodysplasia), may involve large segments of the GI tract. The latter can be associated with life-threatening hemorrhage.

Glomus Tumors

Clinical Features

Glomus tumors are composed of modified smooth muscle cells that are a counterpart of the perivascular glomus body. These tumors occur most commonly in the peripheral soft tissues, especially the distal extremities. Rare cases have been identified within the GI tract, most commonly within the stomach.215 In a study of GI glomus tumors by Miettinen and colleagues,216 all but 1 of 32 glomus tumors were located in the stomach; the only exception was a cecal tumor. These tumors are found more frequently in women. The median age at diagnosis is 55 years, and the presenting signs and symptoms include GI bleeding or ulcer-like symptoms.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

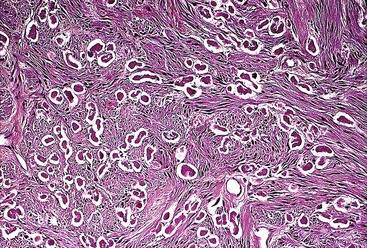

GI glomus tumors typically involve the muscularis propria (Fig. 30.41) and are histologically similar to their peripheral soft-tissue counterparts. The distinctive glomus cell has a round uniform shape and a discrete round nucleus surrounded by pale to eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells are arranged in sheets and nests surrounding hemangiopericytoma-like vascular spaces in a myxoid or hyalinized stroma (Figs. 30.42 and 30.43). Mitotic activity is typically low (<5 per 50 HPFs). Focal atypia and vascular invasion have been observed in rare cases.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

The neoplastic cells are immunoreactive for the muscle markers smooth muscle actin and calponin, whereas there is variable expression of desmin and an absence of staining for S100 protein and KIT. Miettinen and associates also report an elaborate network of pericellular collagen type IV and laminin immunoreactivity in these tumors.216

Treatment and Prognosis

Most glomus tumors in the GI tract behave in a clinically benign fashion. In the study by Miettinen and associates, follow-up of 32 GI glomus tumors revealed development of metastatic disease in only one patient.216 In this case, the primary tumor had cytologic atypia with focal areas of spindle cell morphology, a low mitotic count, and vascular invasion. In long-term follow-up (median 219 months), the remaining patients all have remained disease free.216

Angiosarcoma and Kaposi Sarcoma

Clinical Features

Angiosarcoma of the GI tract is exceptionally rare, described in case reports and small series.217 Involvement of the GI tract by angiosarcoma has been reported mainly in the setting of metastatic disease.218 Kaposi sarcoma (KS) is seen in the setting of immunosuppression; in the United States, it is most commonly described after transplantation or as an AIDS-related malignancy. KS is the most common GI malignancy in the setting of AIDS.219 That said, the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has dramatically reduced but not eliminated the incidence of KS. Patients with either angiosarcoma or KS may be asymptomatic, or they may experience weight loss, nausea, vomiting, GI bleeding, or diarrhea.220 Its endoscopic appearance ranges from multiple purple maculopapular lesions to larger nodular and polypoid tumors.221,222

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

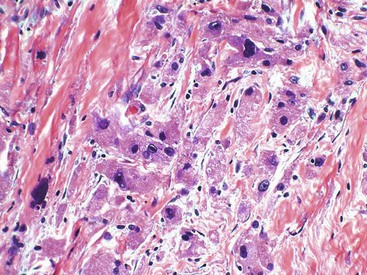

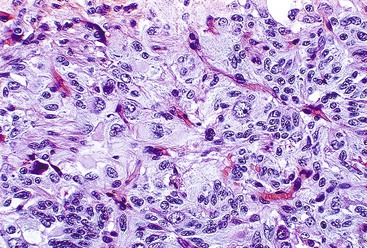

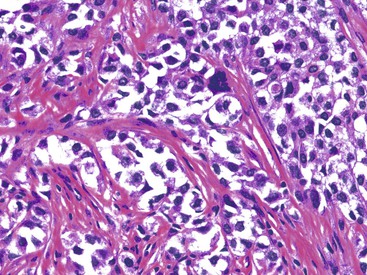

Grossly, both lesions can have a varied appearance as polypoid mucosal nodules, mucosal ulcerations, or mural and serosal masses with prominent hemorrhage. Angiosarcoma is typified by the presence of spindled or epithelioid cells that form primitive vascular channels that dissect through the tissue. In the GI tract, epithelioid morphology is common and may mimic a poorly differentiated carcinoma (Figs. 30.44 and 30.45).217 The presence of only rudimentary lumen formation or rare intracytoplasmic lumina can also confound the diagnosis. Histologically, KS is composed of monomorphic spindle cells that are separated by slitlike vessels and are arranged in vague fascicles. Frequently, PAS-positive, diastase-resistant hyaline globules are present, both intracellularly and extracellularly.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

In both angiosarcoma and KS, the vascular endothelial markers CD31, CD34, ERG, and von Willebrand factor are typically expressed (Fig. 30.46). The more poorly differentiated the histology, the greater the likelihood that expression of CD34 will be diminished. It is important to bear in mind that the epithelioid variant of angiosarcoma may show cytokeratin immunoreactivity that may be diffuse, mimicking carcinoma.217

Human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) has been identified as the causative agent of KS.223 Antibodies to latent nuclear antigen (LAN-1), a protein encoded by HHV8, have shown excellent sensitivity and specificity in identifying KS.224,225

Treatment and Prognosis

Given the rarity of angiosarcoma involving the GI tract, treatment experience is limited. However, localized disease is typically treated with surgical resection, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. As with angiosarcoma in other sites, the course of disease is rapidly progressive despite aggressive therapy.

The behavior of KS depends on several factors including the immune status of the host, the presence of opportunistic infections, and the stage of the disease. Surgery, other than for tissue diagnosis, is not a mainstay of treatment; rather, chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy are the preferred treatment modalities.

Tumors of Adipose Tissue

Lipomas and Liposarcomas

Clinical Features

Lipomas are relatively uncommon tumors in the GI tract. They are most common in the right colon and usually develop as small, submucosal polypoid lesions.226,227 Although many of these lesions are identified incidentally, large lesions may be ulcerated, with some coming to attention secondary to hemorrhage.228,229

Liposarcomas involving the GI tract are exceptionally rare. Most are retroperitoneal, well-differentiated, or dedifferentiated liposarcomas that secondarily involve the gut.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

Lipomas are usually centered in the submucosa and often compress the overlying muscularis mucosae; if large enough, they can cause prolapse-type changes within the adjacent mucosa (Fig. 30.47). Histologically, these tumors are similar to their peripheral counterparts and are composed of mature adipocytes of uniform size. Lipomas lack fibrous septa, nuclear hyperchromasia, or cytologic atypia.

As mentioned previously, liposarcomas involving the GI tract represent secondary involvement from tumors arising in the retroperitoneum. Grossly, these lesions are large and typically encase multiple organs, necessitating a large resection. Well-differentiated liposarcomas/atypical lipomatous tumors (WDLS/ALT) are composed of adipocytes of variable size with scattered enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei that are frequently best appreciated within the fibrous septa that course throughout the lesion. WDLS/ALT may progress to a dedifferentiated liposarcoma that most commonly resembles a pleomorphic undifferentiated sarcoma.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Lipoma is a histologic diagnosis rendered on hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides. Difficulty in establishing a diagnosis of WDLS/ALT can be challenging, especially with small biopsy specimens. That said, the usual clinical scenario is that of a retroperitoneal mass, which can help guide appropriate ancillary testing when one is faced with a lipomatous lesion. WDLS/ALT are typified by giant marker and ring chromosomes230,231 that contain amplified sequences of 12q13-15, resulting in amplification of the MDM2 gene (12q14) as well as other nearby genes. In cases of potential WDLS/ALT that lack diagnostic cytologic atypia, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) to identify the presence of MDM2 gene amplification can be useful.232

Treatment and Prognosis

Lipomas are benign lesions that require treatment if symptomatic. Liposarcomas of the retroperitoneum that involve adjacent organs and are resectable are treated with radiotherapy after resection.

Rare but Noteworthy Entities

Some interesting and noteworthy GI mesenchymal lesions have been described.

Perivascular Epithelioid Cell Tumor

Clinical Features

The umbrella term perivascular epithelioid cell tumor (PEComa) encompasses several mesenchymal lesions that are characterized by myomelanocytic differentiation and are composed of so-called “perivascular epithelioid” cells.233–236 The PEComa family of tumors is now believed to include angiomyolipoma, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, clear cell (“sugar”) tumor of the lung, and the less well-characterized PEComas of numerous other anatomic sites, for which the term “perivascular epithelioid cell tumor, not otherwise specified” (PEComa-NOS) has been proposed.237 Renal angiomyolipoma and pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis are seen frequently in tuberous sclerosis complex.

GI PEComas occur over a wide age range, with almost one third of cases arising in the pediatric population. These tumors are most frequently identified in the colon and rectum; however, involvement of the small bowel, stomach, and gallbladder have been described.238,239 Lesions that are large may cause anemia, abdominal pain, or obstruction, but some examples have been identified incidentally during screening colonoscopy.239

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

Grossly, the lesions may be either small and centered in the mucosa and submucosa or larger (>5 cm) and involve the full thickness of the bowel wall.238,239 Histologically, most PEComas have a nested architecture and are composed of epithelioid cells with round to oval nuclei, variable nucleoli, and clear or granular eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figs. 30.48 and 30.49). Often, the lesional cells condense around blood vessels. Rarely, a spindle cell component is identifiable.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

PEComas show evidence of myomelanocytic differentiation; therefore, they express the melanocytic markers HMB-45 and melan-A, as well as smooth muscle markers.238 Argani and colleagues identified a subset of lesions classified as PEComas that harbor TFE3 gene translocations.240 They suggest that features of this subset of PEComas include a tendency toward young patient age, the absence of an association with tuberous sclerosis, a predominant alveolar architecture and epithelioid cytology, and minimal immunoreactivity for muscle markers.240

Treatment and Prognosis

Some PEComas behave in a benign fashion, whereas others follow an aggressive clinical course; currently, there is uncertainty as to which pathologic features may be predictive of a poor outcome. It is believed that non-GI PEComas with malignant behavior commonly contain areas of coagulative necrosis, a high mitotic index, and marked cytologic atypia.236,239,241 Doyle et al have published a series of 35 GI tract PEComas with outcome; the histologic features in this series that were significantly associated with metastatic disease included marked nuclear atypia, diffuse pleomorphism, and ≥2 mitoses per 10 high power field.239 Resection is the mainstay of treatment while in patients with metastatic disease, mTOR inhibitors have demonstrated some treatment benefit.242

Plexiform Fibromyxoma (Plexiform Angiomyxoid Myofibroblastic Tumor)

Clinical Features

Plexiform fibromyxoma is a recently described distinct entity that has also been reported in the literature under the terms “plexiform angiomyxoid myofibroblastic tumor” and “myxoma.”243–248 The mean patient age is 43 years, with a range from 7 to 75 years; thus far, the male-to-female ratio has been approximately 1 : 1. Most of these tumors have involved the antrum and pyloric region, with presenting symptoms including anemia, gastric ulcer, nausea, and pyloric obstruction. One case was identified incidentally during cholecystectomy.245 On endoscopy, the lesions have been described as submucosal masses, frequently with overlying mucosal ulceration.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

The lesions have a mean size of 6.3 cm (range, 1.9 cm to 15 cm), and they arise in the antrum, with one third of cases extending into the duodenum.243–248 Grossly, the lesions have been described as unencapsulated and lobulated masses that may be submucosal or transmural with serosal extragastric components that may form submesothelial nodules; on cut section, a typical gelatinous or mucoid appearance is appreciated.243–248 Histologically, these lesions have a multinodular appearance at low power, with discontinuous myxoid nodules typically interspersed within the muscularis propria (Fig. 30.50). The myxoid nodules are relatively hypocellular; intercellular or fibromyxoid matrix separate the component spindle cells, which are bland with eosinophilic cytoplasm and inconspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 30.51). Frequently, a rich arborizing capillary network is appreciated within the stroma (Fig. 30.52). Mitotic figures are scarce; the maximum number reported has been 4 per 50 HPFs.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Most of these lesions have shown immunoreactivity within the spindled cells for smooth muscle actin and HHF35, with variable expression of desmin; none of the lesions has shown expression of KIT, CD34, DOG1, ALK, S100 protein, EMA, or cytokeratin AE1/AE3.243–248 Molecular genetic alterations have not been described, and no mutations in KIT or PDGFRA have been identified.245–247

Treatment and Prognosis

Plexiform fibromyxoma appears to be a benign tumor: Neither recurrences nor metastatic disease have been reported after surgical resection. Miettinen and associates reviewed the largest series with long-term follow-up after excision and found that histologic features typically worrisome for aggressive behavior (e.g., ulceration, mucosal invasion, vascular invasion) were not indicative of an adverse outcome.247

Gastrointestinal Clear Cell Sarcoma–Like Tumor

Clinical Features

Clear cell sarcoma (CCS), as described by Enzinger, is a neoplasm that arises adjacent to tendons and aponeuroses of the distal extremities and shows evidence of melanin production.249 However, CCS may also arise primarily within the GI tract. These lesions have been observed in both children and adults and are most frequently identified in the small bowel.250–256 Depending on the site of involvement, patients may experience obstruction or have nonspecific complaints of abdominal pain, nausea, or diarrhea. Although soft tissue CCS and GI CCS-like tumors share the same translocation involving EWSR1, in most (but not all cases) there are histomorphologic and immunohistochemical differences between the two. These differences have led some authors to suggest that these are not simply the same lesion within different anatomic sites257,258; they have suggested the name malignant GI neuroectodermal tumor (GNET) for lesions that lack melanocytic differentiation.259

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

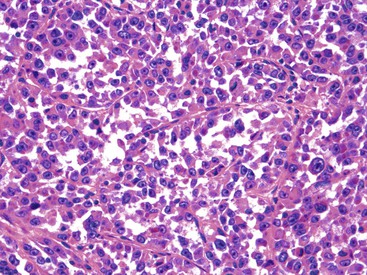

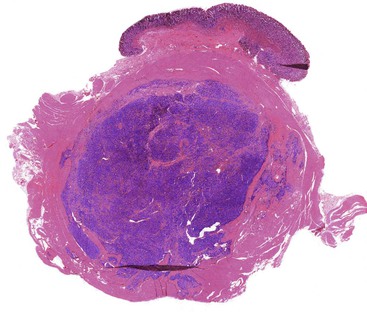

These lesions typically involve the full thickness of the bowel wall, with ulceration of the overlying mucosa (Fig. 30.53). Similar to soft tissue CCS, GI CCS-like tumors may have areas of a nested architecture caused by prominent fibrous tissue septa that divide the tumor. However, other architectural patterns are common, including sheetlike or alveolar growth. The neoplastic cells have eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm and may be round, oval, or spindled. The nuclei have an overall uniform appearance, with vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli; mitotic activity is frequent (Fig. 30.54). GI CCS-like tumors often have prominent osteoclast-like giant cells (Fig. 30.55), in contrast to soft tissue CCS, which may have rare multinucleated giant cells with peripherally placed nuclei.252

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

Virtually all soft-tissue CCS and GI CCS-like tumors express S100 protein, with most soft tissue CCS also showing evidence of melanin production with the expression of HMB-45, melan-A, and MiTF,260–262 as well as ultrastructural evidence of melanocytic differentiation.260,263 Most GI CCS-like tumors have lacked evidence of melanin production by immunohistochemistry.252,256,258,259 However, those GI CCS-like tumors that morphologically resemble soft tissue CCS have shown expression of melan-A and HMB-45.256,258,264 NSE, synaptophysin, and CD56 may be focally positive in GI CCS-like tumors, whereas KIT, smooth muscle markers, and cytokeratin AE1/AE3 are negative.259

Soft-tissue CCS and GI CCS-like tumor are cytogenetically similar, with both lesions having an alteration of EWSR1 (22q12). Most soft tissue CCS have a t(12,22)(q13;q12) chromosomal rearrangement that results in an EWSR1-ATF1 fusion protein,264–266 and several GI CCS tumors have been shown to harbor either an EWSR1-ATF1252,258,259 or an EWSR1-CREB1 fusion protein.256,259

Treatment and Prognosis

Although the number of cases with follow-up is limited, GI CCS appears to have an aggressive behavior, with frequent regional lymph node and liver metastases.252

Synovial Sarcoma

Clinical Features

Synovial sarcoma most commonly occurs in the extremities and harbors a characteristic t(X;18)(p11;q11) rearrangement that results in a SYT-SSX fusion transcript. Rare primary cases of synovial sarcoma have been documented within the GI tract, most commonly in the esophagus and stomach, with case reports of synovial sarcoma in the rectum and duodenum.267–273 Makhlouf and colleagues compiled a series of 10 gastric synovial sarcomas, the largest to date; they reported a roughly equal gender distribution and a mean age of 52 years at diagnosis.270

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

The most common description is that of a submucosal polypoid mass that has a luminal component. Although monophasic, biphasic, and poorly differentiated morphologies have been described within these lesions involving the GI tract, the monophasic pattern has predominated (Fig. 30.56). This pattern is composed of elongated, uniform spindle cells with tapered nuclei growing in a haphazard arrangement, with alternating relatively hypocellular areas adjacent to hypercellular areas. A variably collagenous background may be present.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

As in their peripheral counterparts, focal keratin or EMA expression may be seen, but there is no expression of CD34 or KIT. Identifying either the SYT-SSX fusion transcript or the presence of an SYT rearrangement by FISH is an important ancillary test to establish this diagnosis.

Treatment and Prognosis

The prognosis of these lesions is variable and appears to be dependent on tumor size and differentiation, with larger tumors and those containing a poorly differentiated component exhibiting aggressive behaviour.270

Gastroblastoma and Duodenoblastoma

Clinical Features

Most epitheliomesenchymal biphasic tumors in the GI tract represent high-grade carcinosarcomas that typically arise in the older population and follow an aggressive clinical course.274–278 However, in 2009, Miettinen and associates published a small series of a novel epitheliomesenchymal biphasic tumor of the stomach that occurred in a young patient group and was typified by bland epithelial and mesenchymal components without overt nuclear pleomorphism—the so-called gastroblastoma.279 Since that time, two additional case reports have been published identifying a similar lesion within the stomach,280,281 and a recently published case report describes a similar lesion within the duodenum. The authors suggest the possibility of a duodenoblastoma.282 In all accounts, the lesions occurred in younger individuals (age range, 9 to 30 years). Four of the five gastroblastomas were seen in males, and the one duodenoblastoma was identified in a postpartum female.

Pathologic Features

Gross and Microscopic Findings

The tumors have ranged in size from 3.8 to 15 cm and were described as multinodular with cystic areas. They have shown variable involvement of the gastric wall and may be transmural or limited to the muscularis propria or serosa. Microscopically, they contain varying proportions of epithelial and mesenchymal elements with an overall infiltrative growth pattern. The mesenchymal component consists of a uniform population of mildly atypical, spindled to ovoid cells with blunt-ended nuclei. The epithelial component is variable, with primitive epithelioid clusters merging with the spindled component; more well-developed tubules with open lumina containing eosinophilic inspissated secretions have also been described. Mitotic figures are also variable, with some cases essentially devoid, whereas one case had up to 30 mitotic figures per 50 HPFs. Importantly, neither the epithelial nor the mesenchymal components have shown the requisite atypia to be diagnostic of carcinoma or sarcoma.

Immunohistochemistry and Molecular Findings

The epithelial components have uniformly been found to express cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, whereas expression of high-molecular-weight cytokeratins has been negative and that of EMA has been variable. With respect to the spindled cell component, immunoreactivity for CD10 and vimentin has been identified, but no expression of CD34, KIT, smooth muscle actin, CD99, or desmin has been reported. The duodenoblastoma described had similar cytokeratin staining of the epithelial component, but the spindled component showed immunoreactivity for vimentin, desmin, focal smooth muscle actin, and CD99. Importantly, none of these lesions had evidence of an SYT gene rearrangement, distinguishing them from synovial sarcoma, which would fall into the differential diagnosis given the biphasic nature of the lesion.

Treatment and Prognosis