Mental State and Higher Function

1 MENTAL STATE

BACKGROUND

In this section, examination of higher function has been separated from examination of mental state. This is because higher function can be examined using relatively simple tests, while mental state is examined using observation of the patient and attention to points within the history.

The mental state relates to the mood and thoughts of a patient. Abnormalities may reflect:

• neurological disease, such as frontal lobe disease or dementia

• psychiatric illness secondary to neurological disease (e.g. depression following stroke).

Mental state examination attempts to distinguish:

• diffuse neurological deficit

• primary psychiatric illness such as depression or anxiety presenting with somatic symptoms

• psychiatric illness secondary to, or associated with, neurological disease.

The extent of mental-state testing will depend on the patient and his problem. In many patients, only a simple assessment will be needed. However, it pays to consider whether further evaluation is needed in all patients.

Methods of formal psychiatric assessment will not be dealt with here.

WHAT TO DO AND WHAT YOU FIND

Appearance and behaviour

Watch the patient while you take the history. Here are some questions you can ask yourself in assessing appearance and behaviour.

Are there signs of self-neglect?

Does the patient appear depressed?

Does the patient appear anxious?

Does the patient behave appropriately?

• Overfamiliar and disinhibited or aggressive: consider frontalism.

• Unresponsive, with little emotional response: flat affect.

Does the patient’s mood change rapidly?

Does the patient show appropriate concern about his symptoms and disability?

Mood

Ask the patient about his mood.

If you consider that the patient may be depressed, ask:

• During the past month have you often been bothered by:

a) feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

A positive response to either (a) or (b) along with a request for help is a sensitive and specific screening test for depression.

Patients with schizophrenia often have an apparent lack of mood—blunted affect—or inappropriate mood, smiling when you expect them to be sad—incongruous affect.

In mania, patients are euphoric.

Vegetative symptoms

Ask the patient about vegetative symptoms:

Look for symptoms of anxiety:

Delusions

A delusion is a firmly held belief, not altered by rational argument, and not a conventional belief within the culture and society of the patient.

Delusional ideas may be revealed in the history but cannot be elicited by direct questioning. They can be classified according to their form (e.g. persecutory, grandiose, hypochondriacal) as well as by describing their content.

Delusions are seen in acute confusional states and psychotic illnesses.

Hallucinations and illusions

When a patient complains that he has seen, heard, felt or smelt something, you must decide whether it is an illusion or a hallucination.

An illusion is a misinterpretation of external stimuli and it is particularly common in patients with altered consciousness. For example, a confused patient says he can see a giant fist shaking outside the window, which is in fact a tree blowing in the wind outside.

A hallucination is a perception experienced without external stimuli that is indistinguishable from the perception of a real external stimulus.

Hallucinations may be elementary—flashes of light, bangs, whistles—or complex—seeing people, faces, hearing voices or music. Elementary hallucinations are usually organic.

Hallucinations can be described according to the type of sensation:

Before continuing, describe your findings, for example: ‘An elderly unkempt man, who responds slowly but appropriately to questions and appears depressed’.

WHAT IT MEANS

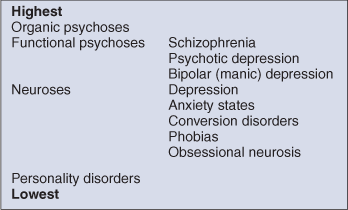

In psychiatric diagnoses there is a hierarchy, and the psychiatric diagnosis is taken from the highest level involved. For example, a patient with both anxiety (low-level symptom) and psychotic symptoms (higher-level symptom) would be considered to have a psychosis (Table 3.1).

Organic psychoses

An organic psychosis is a neurological deficit producing an altered mental state, suggested by altered consciousness, fluctuating level of consciousness, disturbed memory, visual, olfactory, somatic and gustatory hallucinations, and sphincter disturbance.

Proceed to test higher function for localising signs.

There are three major syndromes:

Functional psychoses

Personality disorder

This is a lifelong extreme form of the normal range of personalities. For example:

2 HIGHER FUNCTION

BACKGROUND

Higher function is a term used to encompass language (see Chapter 2), thought, memory, understanding, perception and intellect.

There are many sophisticated tests of higher function. These can be applied to test intelligence as well as in disease. However, much can be learned from simple bedside testing.

The purpose of testing is to:

Higher function can be divided into the following elements:

All testing relies on intact speech. This should be tested first. The tests cannot be interpreted if the patient has poor attention, as clearly this will interfere with all other aspects of testing. Results need to be interpreted in the light of premorbid intelligence. For example, the significance of an error in calculation clearly differs when found in a labourer and in a professor of mathematics.

WHEN TO TEST HIGHER FUNCTION

When should you test higher function formally? Obviously if the patient complains of loss of memory or of any alteration in higher function, you should proceed. In other patients the clues that should lead you to test come from the history. Patients are often remarkably adept at covering their loss of memory; vague answers to specific questions, and inconsistencies given without apparent concern, may suggest the need for testing. If in doubt, test. History from the relatives and friends is essential.

When you test higher function, the tests should be applied as:

1. an investigative tool directed towards the problem

2. screening tests to look for evidence of involvement of other higher functions.

For example, if a patient complains of poor memory, the examiner should test attention, short-term memory and longer-term memory, and then screen for involvement of calculation, abstract thought and spatial orientation.

WHAT TO DO

Introduction

Before starting, explain that you are going to ask a number of questions. Apologise for the fact that some of these questions may seem very simple.

Test attention, orientation, memory and calculation whenever you test higher function. The other tests should be applied more selectively; indications will be outlined.

1 Attention and orientation

Orientation

Test orientation in time, place and person:

Make a note of errors made.

Attention

Digit span

Tell the patient that you want him to repeat some numbers that you give him. Start with three- or four-digit numbers and increase until the patient makes several mistakes at one number of digits. Then explain that you want him to repeat the numbers backwards—for example, ‘When I say one, two, three you say three, two, one.’

Note the number of digits the patient is able to recall forwards and backwards.

2 Memory

a Immediate recall and attention

Name and address test

Tell the patient that you want him to remember a name and address. Use the type of address that the patient would be familiar with, e.g. ‘John Brown, 5 Rose Cottages, Ruislip’ or ‘Jim Green, 20 Woodland Road, Chicago’. Ask him immediately to repeat it back to you.

Note how many errors are made in repeating it and how many times you have to repeat it before it is repeated correctly.

Alternative test: Babcock sentence

Ask the patient to repeat this sentence: ‘One thing a nation must have to be rich and great is a large, secure supply of wood.’

b Short-term memory or episodic memory

About 5 minutes after asking the patient to remember the name and address, ask him to repeat it.

Note how many mistakes are made.

c Long-term memory or semantic memory

Test factual knowledge you would expect the patient to have. This varies greatly from patient to patient and you need to tailor your questions accordingly. For example, a retired soldier should know the Commander-in-Chief in the Second World War, a football fan the year England won the World Cup, a neurologist the names of the cranial nerves. The following may be used as examples of general knowledge: dates of the Second World War, an American president who was shot dead.

3 Calculation

Serial sevens

Ask the patient if he is good with numbers, explaining that you are going to ask him to do some simple calculations. Ask him to take seven from a hundred, then seven from what remains.

Note mistakes and the time taken to perform calculation. N.B. These tests require good concentration, and poor performance may reflect impaired attention.

Alternative test: doubling threes

This should be used especially if serial sevens prove too difficult and if the patient professes difficulty with calculations. What is two times three? Twice that? And keep on doubling.

Note how high the patient is able to go and how long it takes.

Further tests

Ask the patient to perform increasingly difficult mental arithmetic: 2 + 3; 7 + 12; 21 − 9; 4 × 7; 36 ÷ 9 etc.

N.B. Adjust to premorbid expectations.

4 Abstract thought

This tests for frontal lobe function: useful with frontal lobe lesions, dementia and psychiatric illness.

What you find

Ask him to explain the difference between pairs of objects: e.g. a skirt and a pair of trousers, a table and a chair.

Ask the patient to estimate: the length of a jumbo jet (70 m or 230 feet); the weight of an elephant (5 tonnes); the height of the Eiffel Tower (986 feet or 300 m); the number of camels in The Netherlands (some in zoos).

5 Spatial perception

This tests for parietal and occipital lobe function.

Clock face

Ask the patient to draw a clock face and to fill in the numbers. Ask him then to draw the hands on at a given time: for example, ten to four.

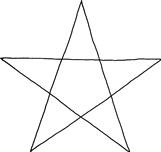

Five-pointed star

Ask the patient to copy a five-pointed star (Fig. 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Five-pointed star

6 Visual and body perception

Tests for parietal and occipital lesions.

Abnormalities of perception of sensation despite normal sensory pathways are called agnosias. Agnosias can occur in all modalities of sensation but in clinical practice they usually affect vision, touch and body perception.

The sensory pathway needs to have been examined and found to be intact before a patient is considered to have an agnosia. However, agnosia is usually regarded as part of higher function and is therefore considered here.

Facial recognition: ‘famous faces’

Take a bedside newspaper or magazine and ask the patient to identify the faces of famous people. Choose people the patient will be expected to know: the US President, the Queen, the Prime Minister, film stars and so on.

Note mistakes made.

Body perception

• Patient ignores one side (usually the left) and is unable to find his hand if asked (hemi-neglect).

• Patient does not recognise his left hand if shown it (asomatagnosia).

Ask the patient to show you his index finger, ring finger and so on.

Ask the patient to touch his right ear with his left index finger. Cross your hands and ask which is your right hand.

Sensory agnosia

Ask the patient to close his eyes. Place an object—e.g. coin, key, paperclip—in his hand and ask him what it is.

Ask the patient to close his eyes. Write a number or letter on his hand and ask him what it is.

7 Apraxia

Apraxia is a term used to describe an inability to perform a task when there is no weakness, incoordination or movement disorder to prevent it. It will be described here, though clearly examination of the motor system is required before it can be assessed.

Tests for parietal lobe and premotor cortex of the frontal lobe function.

Ask the patient to perform an imaginary task: ‘Show me how you would comb your hair, drink a cup of tea, strike a match and blow it out.’

Observe the patient. If there is a difficulty, give the patient an appropriate object and see if he is able to perform the task with the appropriate prompt. If there is further difficulty, demonstrate and ask him to copy what you are doing.

• The patient is able to perform the act appropriately: normal.

• The patient is unable to initiate the action though understanding the command: ideational apraxia.

If inability is related to a specific task—for example, dressing—this should be referred to as a dressing apraxia. This is often tested in hospital by asking the patient to put on a dressing gown with one sleeve pulled inside out. The patient should normally be able to overcome this easily.

Three-hand test

Ask the patient to copy your hand movements and demonstrate: (1) make a fist and tap it on the table with your thumb upwards; (2) then straighten out your fingers and tap on the table with your thumb upwards; (3) then place your palm flat on the table. If the patient is unable to perform this after one demonstration, repeat the demonstration.

WHAT YOU FIND

Three patterns can be recognised:

• Patients with poor attention. Tests are useful to document level of function, but are of limited use in distinguishing focal from diffuse disease. Further assessment is discussed in Chapter 27.

– If of slow onset: dementia or chronic brain syndrome.

– If of more rapid onset: confusional state or acute brain syndrome.

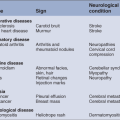

• Patients with deficits in one or only a few areas of testing. Indicates a focal process. Identify the area affected and seek associated physical signs (Table 3.2).

Table 3.2

| Lobe | Alteration in higher function | Associations |

| Frontal | Apathy, disinhibition | Contralateral hemiplegia, Broca’s aphasia (dominant hemisphere), primitive reflexes |

| Temporal | Memory | Wernicke’s aphasia (dominant hemisphere), upper quadrantanopia |

| Parietal | Calculation, perceptual and spatial orientation (non-dominant hemisphere) | Apraxia (dominant hemisphere), homonymous hemianopia, hemisensory disturbance, neglect |

| Occipital | Perceptual and spatial orientation | Hemianopia |

Patterns of focal loss

• Impaired attention and orientation: occurs with diffuse disturbance of cerebral function. If acute, often associated with disturbance of consciousness; assess as Chapter 27. If chronic, limits ability for further testing; this is suggestive of dementia. N.B. Also occurs with anxiety and depression.

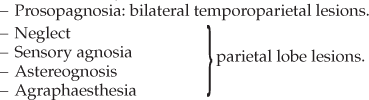

• Loss of spatial appreciation: (copying drawings, astereognosis)—parietal lobe lesions.

• Apraxia:

WHAT IT MEANS

Diffuse or multifocal abnormalities

Rare

Degenerative conditions

Focal deficits

May indicate early stage of a multifocal disease.

TIP

TIP TIP

TIP TIP

TIP TIP

TIP TIP

TIP TIP

TIP