Chapter 15 Mental illness assessment, management of depression and self harm; the Mental Health Act

Introduction

Mental health problems present in between 30% and 60% of primary care consultations.1 One in six men and one in four women will suffer from a mental illness at some point in their lives.2,3 GPs, for example, find that at least 30% (or 1.5 days per week) of their working week concerns mental health consultations. For depression alone, prevalence amongst the adult population in the UK varies between 17–71 per thousand for men and 25–124 per thousand for women.

Unfortunately these patient presentations in primary care are frequently complex and do not always fit easily into diagnostic categories.4 The objectives of this chapter are listed in Box 15.1.

Box 15.1 Chapter objectives

The recognition of primary survey positive patients and those with complex but not immediately life-threatening presentations (primary survey negative patients)

The recognition of primary survey positive patients and those with complex but not immediately life-threatening presentations (primary survey negative patients) The secondary survey, history taking and examination of the patient with signs or symptoms of mental illness

The secondary survey, history taking and examination of the patient with signs or symptoms of mental illnessPrimary survey

A mental illness may cause a patient to take an overdose or injure themselves in such a way that they develop immediately life-threatening ABCD problems. These problems are covered in Chapter 14.

An immediately life-threatening psychiatric situation is where the patient wants to kill themselves, or harm others (Box 15.2), but will not comply with treatment. Management will depend on a large number of factors – not only your assessment of the problem but also the extent and availability of local services.

Secondary survey

Medical assessment is indicated if:

Mental health assessment

While it is difficult to completely separate the mental health assessment into ‘history’ and exam sections, it aids understanding to use the SOAPC system. Effective mental health assessment requires a very sensitive consultation style to gain the patient’s trust and showing the patient that you recognise their distress and experience. Some key principles for the mental health interview are identified in Box 15.3. Consultation skills that improve identification of emotional distress include frequent eye contact, relaxed posture, use of open questions at the beginning of the -consultation, use of minimal verbal prompts while actively listening and avoiding giving information too early in the consultation.

Subjective – history

Information from carers is often of great importance in the assessment. If carers are not present and you are having difficulty, you may have to trace them and discuss the issues (preferably with consent of the patient). Box 15.4 summarises the assessment of a patient with psychiatric symptoms.

Objective information – mental state examination

Perform a brief physical exam, including noting the vital signs (especially pulse, temperature and Glasgow Coma Score). Listing the elements of a mental state examination is an excellent way to bring some structure to what can be a confusing and difficult task. These key elements are listed in Box 15.5. The assessment of social support is often of the greatest importance in deciding a management plan.

Depression

Depression is the most common mental disorder in primary care and covers a range of mental health diagnoses and problems. These are all distinguished by lowered mood and a loss or decrease of interest and pleasure in daily life and experiences. Additionally, there are disorders of thinking, problem-solving and behavioural and physiological symptoms.5 Box 15.6 lists the diagnostic criteria for severe depression but it is often difficult to discriminate between normal mood variations, dysthymia (Box 15.7) and cyclothymic (Box 15.7) episodes and mild to moderate clinical depression.

It is not clear how effective practitioners are at preventing suicide. A number of patients who successfully commit suicide will have consulted a healthcare professional in the immediately preceding period. At least 30% see their GP in the 4 weeks prior to their deaths.6 Improving the recognition of severe depression and its treatment has been the focus –of several studies and training packages for GPs but the long-term data show little sustained difference.

Each year people with depression account for two-thirds of all deaths from suicide nationally (Box 15.8). Risk assessment tools and rating scales can be very helpful, e.g. the Suicide and Self-Harm Risk Assessment Scale (see Chapter 14).

Box 15.8 Additional risk factors for suicide

Recent self harm; history of violent self harm (half of those who commit suicide will have self-harmed in the past10,11)

Recent self harm; history of violent self harm (half of those who commit suicide will have self-harmed in the past10,11) Depression – paradoxically as a patient starts to recover from severe depression they regain the capacity to act

Depression – paradoxically as a patient starts to recover from severe depression they regain the capacity to act Chronic illness: including HIV/AIDS, cancer, diabetes, post-stroke (especially when communication centres affected), Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (where some insight remains)

Chronic illness: including HIV/AIDS, cancer, diabetes, post-stroke (especially when communication centres affected), Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease (where some insight remains)Treatment and referral

Prior to the Mental Health National Service Framework (MHNSF) the traditional management of the at-risk suicidal patient was by admission to an acute mental health unit. In non-scheduled and out-of-hours care, this may be difficult due to bed shortages, high acute in-patient bed –occupancy (often in excess of 100%) and implementing MHA processes for detaining at-risk patients unwilling to agree to admission. Currently there is growth in managing these patients in the community with Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment Teams (CRHTTs) (Box 15.9). These offer intensive community-based interventions in the patient’s own home (MHNSF target of 335 CRHTTs by 2005). Where such teams exist, a referral both ‘in-hours’ and ‘out-of-hours’ to the local CRHTT should be made. The CRHTT will undertake a comprehensive mental health and risk assessment. As appropriate, a treatment, support or monitoring package will be implemented.

Box 15.9 Treatment options

full psychosocial assessment (as recommended by NICE10,11) and referral or brief interventions offered as appropriate; may offer specific alcohol and substance misuse service

full psychosocial assessment (as recommended by NICE10,11) and referral or brief interventions offered as appropriate; may offer specific alcohol and substance misuse serviceDifferentiating between suicide and deliberate self-harm

The MHNSF indicates that overall the rate of suicide is dropping.7 Men are 3× more likely than women to commit suicide; women are 3–4× times more likely to present with deliberate self-harm by overdosing, cutting or other means.8 Whilst suicide is rare, a population of 250 000 would have about 25 suicides per annum. The term deliberate self-harm (DSH) indicates that the person hurts themselves, either to signal distress, in crisis and where coping strategies are limited and to release/manage overwhelming feelings.9 Whilst there may be no ‘intention’ to kill themselves the person who is self-harming does increase the risk of death with each occasion of this behaviour. NICE identify that there are -150 000 attendances at A&E each year resulting from DSH – therefore being one of the top five causes of acute medical admission.10

So why do patients self-harm? Four main themes regarding motivation emerge from experiential and empirical research evidence. Some find this the best way of handling and expressing overwhelming feelings or of escaping numbness/unreality and confirming one’s existence. It can be a method of obtaining or maintaining a sense of control. In some it is a continuation of past abusive patterns (adapted from Doy8). Behaviour always has a meaning – we often do not appreciate what it means for the person.

If the client is not primary survey positive undertake a psychosocial and needs assessment and a risk assessment (see Chapter 14). Recognise the distress associated with deliberate self-harm and treat the person with respect. Assume the patient has the capacity to make decisions about their care unless there is evidence to the contrary. Offer full information and seek consent to make appropriate referrals.

You may provide the patient with alternatives to self-harming including help-line contact and for pre-hospital workers to consider referral for psychotherapy. Many social care or voluntary agencies may be effective in supporting the patient with relationship, accommodation, financial, substance misuse, abuse and violence issues (Box 15.10).

The Mental Health Act

Patients who have a mental disorder requiring immediate treatment commonly consent to treatment. Only around 10% of those admitted to Mental Health Hospitals are there against their will under a ‘Section’ of the Mental Health Act (MHA).

Definitions

The four sub-categories of Mental Disorder are further defined.

1 Mental illness

There is no legal definition but there are many terms and definitions, see for example the JRCALC Clinical Practice Guidelines11 or the International Classification of Diseases, version 10.12 Mental illness may be defined as a number of conditions typically involving impairment of an individual’s normal cognitive (thinking), emotional, or behavioural functioning. It can be precipitated by biopsychosocial, biochemical, normal and traumatic life events, genetic or other factors, including infection or head injury.

The following are some of the potential characteristics of mental illness presentations:

Treatment options

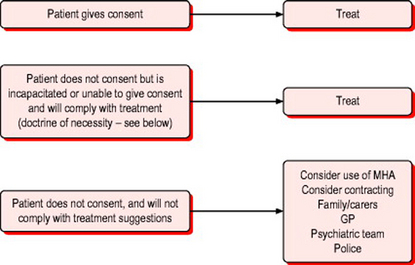

Use of the MHA is strictly defined (Fig. 15.1). ‘Informal’ patients are either:

admitted and treated under the Common Law doctrine of:

Most importantly, unless the patient has been detained under a relevant section of the MHA (currently section 3), if they have capacity they may legally refuse treatment, even if they are suffering from a mental disorder. Even if detained under section 3, only treatment for the mental disorder can be legally imposed in a patient with capacity. Treatment for a physical disorder which is not associated with the mental illness cannot be imposed under these circumstances.

Assessment of valid consent

An underlying principle of medical care is that consent should always be sought before any intervention is commenced. Treatment without valid consent may lead to charges of assault, or battery or worse, but there are situations where it is necessary to treat a patient without consent. There is sometimes a difficult conflict between the patient’s right to determine their own treatment and the professional responsibility to act ‘in the patient’s best interests’. Failure to intervene and care for a patient who cannot give valid consent may lead to charges of negligence.

The Mental Capacity Act13 gives clear guidance in this area. A good understanding of the principles of this legislation and its application to practice empowers not only the practitioner, but also the patients with whom we work.

In a large majority of cases the authority for examination and treatment is established by the patient giving their valid consent. Issues of consent in children are discussed in Chapter 5 (pages 87–89). The discussion in this section applies to adults. Valid consent comprises four components. The absence of any one component will render the consent invalid. For consent to be valid the patient should be able to:14

use the information as part of the decision-making process and understand the consequences of their decision

use the information as part of the decision-making process and understand the consequences of their decisionCapacity

1 Mental Health After Care Association. First national GP survey of mental health in primary care. London: MACA, 1999.

2 Department of Health. Modern standards and service models: mental health. London: NHSE, 1999.

3 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Depression: the management of depression in primary and secondary care, 2004. Available online http://www.nice.org.uk/ (5 Mar 2007)

4 Mynors-Wallis L, Moore M, Maguire J, Hollingbery T. Shared care in mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002.

5 World Health Organization. WHO Guide to mental health in primary care. London: Royal Society of Medicine, 2000.

6 Evans J. Suicide, deliberate self-harm, and severe depressive illness. In: Elder A, Holmes J, editors. Mental health in primary care. Oxford: OUP, 2002.

7 Department of Health. National suicide prevention strategy for England. London: DoH, 2002.

8 Doy R. Women and deliberate self-harm. In: Boswell G, Poland F, editors. Women’s minds, women’s bodies: an interdisciplinary approach to women’s health. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

9 Burstow B. Radical feminist therapy: working in the context of violence. London: Sage, 1992.

10 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Self-harm: the short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care, 2004. Available online http://www.nice.org.uk (5 Mar 2007)

11 Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee. Clinical practice guidelines version 3.0. University of Warwick/ASA/JRCALC, 2004. Available online http://www.nelh.nhs.uk/emergency (5 Mar 2007)

12 World Health Organization. ICD-10 Classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva: WHO, 1992.

13 http://www.dca.gov.uk/menincap/legis.htm#reldocs.

14 http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/research/hsri/emergencycare/ jrcalc_2006/guidelines.

BMA. Guidance for general practitioners: medical examinations and medical recommendations under the Act. London: BMA, 1999.

Department of Health. Reference guide to consent for examination or treatment. London: DoH, 2001.

Hatton C, Blackwood R. Examination of the mental state. Lecture notes on clinical skills, 4th edn. Blackwell Science, Oxford, 2003.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The NICE website contains clinical guidelines for depression and anxiety, also for schizophrenia and self-harm. www.nice.org.uk. (5 Mar 2007)