CHAPTER 5 Menstrual Wellness and Menstrual Problems

The scientific study of menstruation has been hampered by the overpowering influence of traditions and social and cultural beliefs. We have all, men and women, been conditioned to view menstruation in a negative way. Perhaps, it is time to look at menstruation from another point of view. How many fine novels have been finished in a burst of creativity in the premenstrual period? How many great ideas have been born premenstrually?

MENSTRUAL HEALTH AND THE NORMAL MENSTRUAL CYCLE

This section reviews the historical and cultural beliefs and attitudes surrounding menstruation, “the normal menstrual cycle,” and provides an overview of the menstrual irregularities and conditions presented later in this chapter. This section also looks at practical ways to promote menstrual health. Subsequent sections of Chapter 7 address common menstrual problems.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF MENSTRUATION IN CULTURE AND MEDICINE

Menstruation has historically been cloaked by religious, social, and cultural myths and meaning. Menstrual blood and menstruating women have been surrounded by fear, taboo,* restrictions, and worship since ancient times. Cultural views on menstruation are diverse. The Beng people of the Ivory Coast believed that “Menstrual blood is special because it carries in it a living being. It works like a tree. Before bearing fruit a tree must first bear flowers. Menstrual blood is like the flower.”2 In stark contrast it has been referred to as “the curse” by Judeo-Christians and is considered a sign of uncleanliness, or even evil, in some cultures.3 Menstrual blood was used as a panacea, a medicinal ingredient, an ingredient in casting spells, and even as a pesticide capable of making caterpillars drop from plants and insects die in the fields.4 Menstruating women were variably considered to be possessed by evil spirits or magic. 5 6 7

Medical attitudes regarding menstruation have fluctuated over the centuries, from menstruation and menstrual blood being perceived as a natural process—a woman’s “flowers,” as menstruation was described not only by the Beng but in the Treatise on the Diseases of Women, and Conditions of Women, part of the medieval compendium known as The Trotula, which remained the definitive text on women’s medicine for several centuries—to something capable of poisoning men and deforming children, as described by Pliny and others.2,7 Hildegarde of Bingen, the famed German nun and healer (1098–1179) used the term flowers; however, she also attributes menstruation to “Eve’s sin in Paradise,” reflecting both positive and negative attitudes toward menstruation. Hippocratic and Galenic medicine viewed menstruation as the basis of women’s unique physiology. It was considered a necessary and healthy purgation upon which the health of the entire female body was dependent. Menstruation was seen as women’s inherent constitutional “coldness.” The inabilities to “cook” their nutrients thoroughly led to an accumulation of waste in the body that could only be gotten rid of through menstruation. Lack of menses (e.g., amenorrhea) was believed to lead to a pathologic systemic state. Normal menstruation, that is, the proper amount at the proper time, was considered to reflect a state of health.2

In contrast, however, around the first century bce, Pliny, a physician and prolific medical writer, wrote that menstrual blood could drive men and dogs mad, make vines wither, sour wine, and discolor mirrors, among other powers.5,7,8 Pliny’s views, as well as others’ of his time, represented menstruation as poisonous or noxious, views that would contribute to misogynist medical views of women that have persisted.1,2,4 Democritus wrote that “usually the growth of greenstuff is checked by contact with a woman; indeed, if she is also in the period of menstruation, she will kill the young produce merely by looking at it.”6

Negative attitudes about menstruation have not only influenced the practice of women’s medicine, but also the medical education of women. Western medicine historically viewed menstruation as a disease and an opportunity to treat women as fragile and weak.7 Well into the nineteenth century in the United States, the fact that women menstruated was considered proof of the inferiority of the female intellect. Menstruation was used as a justification for keeping women out of medical schools, based on the grounds that menstruating women needed increased rest—mentally and bodily.5

Women’s health reform and self-help movements throughout the twentieth century have played a major role in transforming and reshaping women’s, society’s, and medicine’s attitudes toward menstruation. It has become a more acceptable topic for conversation, evidenced in many ways, not in the least, by the mention of menstruation on television sitcoms, the openness of menstrual products advertisements on television and in print media, and articles in popular magazines. This is a positive trend allowing women to more openly seek information and medical care about menstruation and menstrual concerns. However, advertising also directly contributes to the perpetuation of cultural menstrual taboos—that menstruation is “dirty,” and suggestions that it should remain hidden. Educational films and advertisements from menstrual product manufacturers stress products’ abilities to keep safe the secret that the girl is menstruating and to help her feel fresh and clean, perpetuating the message that menstruation is shameful and dirty.9

Women’s own personal and cultural views on menstruation also vary substantially. Menstruation may be considered a happy event, or a sign of uncleanliness—both attitudes persisting even in a single culture.10 A correlation has been asserted in feminist literature that a woman’s attitudes toward menstruation and can influence her physical experience of menstrual symptoms.7 In one study analyzing menstrual attitudes, women were asked to describe their menstrual periods. Terms were rated as positive (such as “red friend,” “my buddy”), negative (such as “the curse,” “pain in the ass”), or neutral (such as “period,” “surfin’ the crimson wave”). In the groups combined, most terms were either neutral (46%) or negative (37%). There was a tendency for women in the negative group to employ negative terms (52% of negative group women used solely negative terms versus 18% in the positive group), whereas 55% of women in the positive group employed neutral, not negative terms.9 Women in the negative group used negative terms significantly more than did women in the positive group. Many women consider menstruation somewhat of an inconvenience, but nonetheless, a natural event. Increasingly, American women are reframing menstruation as a celebration of women’s femininity and women’s connection to the rhythms of the earth and the moon.

WHAT IS NORMAL MENSTRUATION?

It is necessary to determine whether a pattern, symptom, or concern is normal for the individual woman in the context of her own gynecologic and menstrual history, as well as against objective measures. Certain characteristics of menstruation can be a reflection of an underlying pathologic process or may predispose a woman to the development of chronic disease.11 For example, metrorrhagia predisposes to anemia, and the irregular menstrual cycles associated with PCOS (see PCOS) can predispose a woman to diabetes and consequently, heart disease. Women with long or highly irregular menstrual cycles have a significantly increased risk for developing type 2 DM that is not completely explained by obesity.12 Persistent deviations from the woman’s own norms, as well as major deviations from accepted standards, require further evaluation.

ONSET, FREQUENCY, AND DURATION OF MENSTRUATION

A woman will experience from 300 to 400 menstrual cycles in her lifetime. Cycle length is controlled by the rate and quality of follicular growth and development, which varies in individual women.1 Based on several observational longitudinal studies of thousands of women around the world, it was determined that at age 25, 40% of women had 25- and 28-day cycles, and from ages 25 to 35 60% had 25- to 28-day cycles. The average cycle length is 26 to 34 days.13 Only 0.5% of women experience cycles shorter than 21 days and 0.9% cycles longer than 35 days. At least 20% of women experience irregular cycles.1 The length of the follicular phase is the primary determining factor in cycle length.

Menstrual bleeding lasts 3 to 6 days in most women, although there is variation in cycle length from 2 to 12 days after the start of ovulatory cycles. Longer periods (>8 days) are associated with anoluvation.13 The heaviest flow is consistently on day 2 of the cycle. Normal blood loss is considered 30 to 80 mL. Small clots are considered normal; large clots may suggest the need for further evaluation.7

The duration and amount of bleeding declines slightly (by about a half a day per cycle) in women over age 35. However, women approaching menopause often experience significantly heavier bleeding than younger women.13

Women in their late thirties and forties often begin to experience some degree of irregularity of menstrual frequency, duration, and amount of blood loss because of a decline in ovarian function as they approach menopause. In their late thirties, women experience a shortening of their cycle because of increased production of FSH, a result of follicle numbers beginning to decline. However, between 2 and 8 years prior to menopause, the cycles again lengthen.1 Approximately 50% of women experience a cycle of 120 days or longer in the year prior to menopause, and 20% experience a cycle of this length or longer within 2 to 4 years of their final period.13 The average age of menopause in the United States is 51 years old.14

FREQUENCY AND TYPES OF MENSTRUAL DISORDERS

Menstrual dysfunction is defined in terms of bleeding patterns, for example, amenorrhea (lack of menstruations), menorrhagia (excessive bleeding during menstruation), or polymenorrhea (frequent menstruation); ovarian dysfunction for example, anovulation and luteal deficiency; pain (dysmenorrhea); and premenstrual syndrome. Irregular menstruation is estimated to range from 2% to 5% of the general population, and up to 66% among athletes.15 In the United States, approximately 2.9 million office visits are made annually by women age 18 to 54 for menstrual problems.7,16 Two-thirds of these women contact a doctor regarding menstrual problems each year, and 31% report spending a mean of 9.6 days in bed annually. Among young women, dysmenorrhea is the most common cause of time lost from work or school. The costs of menstrual disorders to US industry have been estimated to be 8% of the total wage bill, and the impact is particularly acute in industries that employ women predominantly.16 Interestingly, it is estimated that primitive, hunter gatherer women, over the course of an average lifetime, experienced only one-third as many menstrual periods as do modern women because of later age at menarche, earlier and more frequent pregnancies, and breastfeeding, suggesting that modern women experience a significantly greater lifetime exposure to estrogen, which may be partially responsible for increased health risks. Traditionally, factors such as later menarche, earlier first pregnancy, breastfeeding, and earlier menopause may have played a protective effect against, for example, breast and gynecologic cancers.16 Menstrual disorders also predispose women to other risks, for example, anemia, osteoporosis, cancer risks, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease.

In spite of the significance of menstruation in women’s lives and the high incidence of menstrually related health problems in society, there is surprisingly little epidemiologic evidence on menstrual disorders and associated risk factors, and no prioritization of research in this area.11,16

Subsequent sections of this chapter address these dysfunctions either individually or as part of a larger syndrome in which they occur.

FACTORS AFFECTING THE MENSTRUAL CYCLE

Diet/Nutrition

Menstruation is influenced by the amount of energy provided by the diet as well as by the types of foods consumed. Lean women with a low body mass index (BMI), as well as obese women, have an increased likelihood of menstrual disorders. Women with highly restrictive dietary practices are more likely to experience menstrual dysregulation, particularly amenorrhea, anovulation, and a shorter luteal phase. 17 18 19 Recent studies suggest that reduced energy availability (increased energy expenditure with inadequate caloric intake) is the main cause of the central suppression of the hypothalamic pituitary-gonadal axis. As a consequence, not only will there be menstrual dysregulation but a higher potential for bone demineralization and increased risk of skeletal fragility, fractures, vertebral instability, curvature, and osteoporosis.19,20 Thus, the importance of treating underlying dietary imbalances that can cause menstrual dysregulation becomes more significant.

Dietary fat restriction is associated with amenorrhea even in normal weight, nonathletic women.11 A raw foods diet is commonly associated with low BMI, weight loss, and amenorrhea. In one study of 279 women on a raw foods diet, 30% of women under age 45 experienced amenorrhea.21 There is a common belief among adolescent girls and women that a vegetarian diet leads to weight loss; thus, many adopt a vegetarian diet as part of an attempt to diet. It has been suggested that a vegetarian diet is associated with menstrual disorders, especially amenorrhea; however, it appears that healthy, weight-stable, vegetarian women consuming self-selected diets do not experience more menstrual disturbances than healthy, weight-stable nonvegetarians.11,22 There does not appear to be a correlation between a higher intake of soy foods in the vegetarian diet and menstrual dysregulation, as has been commonly assumed.22

The consumption of fruits, fish, and vegetables plays a protective effect against dysmenorrhea in adolescent girls and women. The protective role of the fish seems to be due to omega-3 fatty acids. During menstruation, this fatty acid competes with the omega-6 fatty acids for the production of prostaglandins and leukotrienes. The prostaglandins generated from the omega-3 fatty acids lead to a reduction in myometrial contraction and vasoconstriction.23

Weight

Overall weight and changes in weight affect menstrual regularity. Ovarian suppression can occur as a result of sudden or moderate weight loss, leading to amenorrhea. This is most pronounced in cases of eating disorders and famine. This phenomenon is also seen in women who are 20% in 30% below their ideal body weight, which is common in athletes or women on restricted caloric intake diets.11 Obesity, particularly truncal obesity, is also associated with menstrual disorders, notably amenorrhea associated with polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), and an increase in incidence of diabetes and long-term health consequences. It appears that at both ends of the extreme spectra of weight, women are likely to have the longest menstrual cycles and anovulation.11,24

Caloric restriction itself, even before there is a loss of weight, can result in menstrual dysregulation. It was demonstrated in one study that girls who simply skip breakfast experience a higher degree of dysmenorrhea than girls who eat an adequate daily breakfast.25 The effects of body weight on menstrual function may be a result of nutritional status, caloric intake, stress on eating habits and the effects on menses, psychiatric disorders associated with weight problems, or the mechanics of body fat on steroid hormone synthesis and estrogen metabolism.11 Significantly, excessive exercise with menstrual irregularity can be an important sign of an eating disorder, psychological restraint issues around food consumption, higher perceived stress, and low self-esteem.26,27

Exercise

Moderate exercise from a young age is essential for optimal lifelong health including prevention of cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, and depression. However, excessive exercise or exercise at elite levels for competitive athletes can predispose women to nutritional deficiency, inadequate energy intake, and low body weight, all of which increase risk of menstrual dysfunction. Women athletes have a higher overall incidence of menstrual disorders. Ballet dancers and runners have an increased rate of amenorrhea, anovulation, and luteal phase defects compared with nonathletes.11 In one study examining the role of nutritional status, eating behaviors, and menstrual function in 23 nationally ranked female adolescent volleyball players, these women were found to be low in folate, iron, calcium, magnesium, zinc, B complex, vitamin C, and carbohydrate intake, compared with RDAs. Approximately 50% of the athletes reported actively “dieting.” Past or present amenorrhea was reported by 17% of the athletes and 13% and 48%, reported past or present oligomenorrhea and “irregular” menstrual cycles, respectively.28 Among women age 29 to 31, daily vigorous sports activity was associated with increased cycle variability and cycle length. Even recreational exercise is associated with an increase in mean cycle length.11

Exercise is an independent factor separate from weight loss in relationship to cycle variation and presence of amenorrhea. Cessation of training even in the absence of weight gain can restore cycle normalcy. The most likely mechanism of cycle irregularity due to moderate exercise is decreased GnRH and gonadotropin and reduced serum estrogen levels, along with a possible physiologic stress response mechanism. However, because of the increased likelihood of aberrant eating patterns in amenorrheic athletes, inadequate caloric intake and a negative energy balance also may be causative.11 With a societal emphasis on a lean body, many young women use exercise as a means of weight control, frequently combined with rigorous dieting patterns; thus, exercise patterns should be evaluated in the context of ruling out eating disorders, and proper amounts of exercise encouraged to ensure its benefits.

Stress

Most women have experienced, at least once in their lives, the effects of stress on menstrual regularity: skipping a period or having a period come late or early during a particularly difficult time. There is some evidence regarding connections between socioemotional processes and menstrual functioning. Psychological stress is generally acknowledged in the medical literature to affect menstruation; however, studies on stress and menstrual function are limited, consisting mainly of studies of major life changes, catastrophic events such as war or imprisonment. Studies on the effects of girls leaving home to attend school, the military, or work suggest that separation from home and family increases the likelihood of amenorrhea, but these studies have lacked adequate comparison groups.11 High levels of workplace demand, combined with low levels of perceived control, have been associated with a doubled risk for short menstrual cycle length (e.g., less than 24 days) Characteristics consistent with submission (i.e., introversion, anxiety, low perceived control, and inhibition of aggression) have been shown to be elevated among women seeking treatment for hirsutism and irregular menses compared with women without such conditions. However, this association could reflect the socioemotional consequences of these medical problems and their associated features.29

It is no surprise that delicate HPA and endocrine functions might be disrupted by personal upheaval and stress. Although the mechanisms of stress- and anxiety-related menstrual changes have not been fully elaborated, it is suspected that either central psychogenic disturbances cause changes in the hypothalamus that consequently affect prolactin and endogenous opiate levels, and that stress leads to a systemic physiologic response causing elevated basal cortisol levels, and consequently alterations in hypothalamic response and changes in LH with a reduced pulsatile frequency.11,30

Attitudes and Beliefs about Menstruation

In a survey-based study of college-aged women (n = 327) those who had extremely negative or extremely positive early menstrual experiences were strongly associated with correspondingly negative or positive current menstrual attitudes. There were additional associations between early menstrual experiences and measures of body image and health behaviors. Positive group participants reported more positive body image and better general health behaviors. Results suggest that early menstrual experiences may be related to menstrual experiences later in life.9 Unfortunately, adolescent girls often receive inadequate information or negative messages regarding menstruation from an early age. Although they may receive information on the biological aspects of menstruation from parents, teachers, and other sources, they are often not prepared for the practical aspects of getting their periods, for example, what it feels like or how to take care of themselves while menstruating. Instead, girls are directly and indirectly instructed about (largely negative) cultural beliefs concerning menstruation and the ways in which they will be expected to behave in order to uphold these beliefs. Somaticization of these beliefs may translate into increased difficulty in the menstrual experience, particularly in the form of dysmenorrhea or premenstrual syndrome (PMS). Women with negative menstrual beliefs are more likely to seek menstrual suppression through pharmacologic means.9

Environmental/Work Exposures

Women whose work requires large amounts of physical labor may experience weight loss and subsequent menstrual irregularity. Workplace stress and noise also may contribute to menstrual dysregulation. Occupational chemical exposure has clearly been demonstrated to act on the ovaries; cytotoxic agents, for example, can induce ovarian failure including follicular loss, anovulation, oligomenorrhea, and amenorrhea.11 Many environment pollutants to which women are nearly ubiquitously exposed are now also recognized to be endocrine disruptors.

Pheromones and Menstrual Synchrony

Studies on menstrual synchrony, when women who spend time in close proximity begin cycling together, have yielded conflicting results. Nonetheless, the phenomenon is well known among women who report menstruating at the same time, or close to, that of roommates, daughters, sisters, or close friends; hence, it is casually referred to as “the dormitory effect.” Animal and human studies have shown that social interactions can modify endocrine function. It is suspected that pheromones may reduce menstrual cycle variability among women and synchronize menstruation. Pheromones are airborne chemicals released by one individual that can affect another. Odorless compounds obtained from the axillae of women altered cycles of other women exposed to these compounds.1 However, a wider range of environmental signals may influence menstrual synchrony.11 One study on women’s qualitative experience of menstrual synchrony suggests that the concept of menstrual synchrony frames menstruation as a natural, healthy phenomenon for women.31

PROMOTING HEALTHY MENSTRUATION

Diet, Nutrition, and Body Weight

Avoiding or at least reducing the amount consumed of certain foods also may improve menstrual symptoms. For example, one report found that women with PMS consumed 275% more refined sugar, 79% more dairy products, 78% more sodium, and 62% more carbohydrates than women without PMS. They also consumed 77% less manganese and 53% less iron than symptom-free women. Another study found that consumption of caffeine-containing beverages increased the incidence and severity of PMS in college-age women.33

Exercise

Exercise, especially when regular and frequent, can reduce both physical and emotional menstrual discomforts, improving mood and relieving physical symptoms. The mechanisms for this are not fully understood but may include a reduction in estrogen levels and catecholamine levels, improved glucose tolerance, and increased endorphin levels.33 Moderate exercise also reduces the risk of bone demineralization associated with menstrual dysregulation, especially anovulatory cycles and amenorrhea. Excessive exercise, which is discussed in the preceding, should be discouraged, or at least nutritional and energy requirements should be met and healthy body weight maintained.15,18,20 Yoga and many forms of dance include movements and stretches that can be especially specific for relieving pelvic tension and discomfort associated with dysmenorrhea. Forms of movement that help women to positively experience their body can be helpful in overcoming negative personal attitudes.

Stress

As discussed, stress can contribute to physiologic changes that lead to menstrual dysregulation, and menstrual dysregulation itself can increase a woman’s stress levels. Women can be encouraged to manage time to reduce work load or personal stress, and seek outlets for stress such as meditation, yoga, journaling, counseling, or other healthy means. Learning self-empowerment techniques can be very useful for women with stress-related menstrual dysregulation. Adequate nutritional and caloric intake (especially avoiding hypoglycemia) can reduce stress and improve stress resistance. Reduction in caffeine consumption can also reduce stress. Getting adequate rest is essential. Herbal adaptogens and nervines can be used to improve stress resistance and promote relaxation. Improving attitudes about menstruation can improve reduce the perception of menstrual problems.1

Discourage: Negative self-talk, overwork, poor self-image, poor menstrual attitudes.

Environmental Exposures

Some concern has been raised that standard commercial menstrual products are contaminated with dioxin and/or other organochloride compounds that can lead to reproductive disease, most notably, cancers; asbestos, which is alleged to be included in these products to increase the amount of bleeding, requiring women to use more of the products; and rayon fibers that may cause toxic shock syndrome (TSS). There are numerous Internet articles dedicated to spreading warnings about this topic. The FDA has posted a response to this concern in a paper, “Tampons and Asbestos, Dioxin, & Toxic Shock Syndrome,” segments of which are quoted below.

On the topic of dioxin, the FDA states that:

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has worked with wood pulp producers to promote use of dioxin-free methods because dioxin is an environmental pollutant. Because of decades of pollution, dioxin can be found in the air, water, and ground. Therefore, whereas the methods used for manufacturing tampons today are considered to be dioxin-free processes, traces of dioxin may still be present in the cotton or wood pulp raw materials used to make tampons. Thus, there may be trace amounts of dioxin present from environmental sources in cotton, rayon, or rayon/cotton tampons.34 Regarding rayon and TSS, the FDA states:

Although scientists have recognized an association between TSS and tampon use, the exact connection remains unclear. Research conducted by the CDC suggested that use of some high absorbency tampons increased the risk of TSS in menstruating women. A few specific tampon designs and high absorbency tampon materials were also found to have some association with increased risk of TSS. These products and materials are no longer used in tampons sold in the United States Tampons made with rayon do not appear to have a higher risk of TSS than cotton tampons of similar absorbency.34

Many women, reasonably concerned about the risk of exposure to toxins in menstrual hygiene products, choose instead to purchase only disposable menstrual pads and tampons made from organic cotton and other organic fibers that are non–chlorine bleach manufactured. These offer the convenience of disposability and are more environmentally friendly than many of the larger commercial brands. Still, a smaller group of women prefer to use only washable cotton pads, menstrual sponges, and menstrual cups. Although less convenient than disposables, and possibly offensive to some women as they require handling of the menstrual blood, these are environmentally friendly choices. Careful cleaning of these products after use is essential to avoid risks of infection. In one study of colonization of microorganisms during menstruation among women using various menstrual products, cultures from those from users of sea sponges were found to have significantly higher colonization rates with S. aureus, Escherichia coli, and other Enterobacteriaceae. The association of sea sponges with a high rate of S. aureus colonization suggests that they are not an alternative to tampons for women seeking to decrease the risk of toxic shock syndrome.35

Menstruation and Lunar Cycles

There is anecdotal evidence that moonlight can help to synchronize the menstrual cycle. This author was able to identify only one clinical trial evaluating this phenomenon. A double-blind, prospective study during the fall of 1979 investigated the association between the menstrual cycles of 305 Brooklyn College undergraduates and their associates and the lunar cycles. All subjects were 19 to 35 years old and using neither oral contraceptives nor the IUD. Approximately one-third of the subjects had lunar period cycles (i.e., a mean cycle length of 29.5 ± l day). Almost two-thirds of the subjects started their October menstrual cycle in the light half of the lunar cycle, significantly more than would be expected by random distribution. The author concluded that there is a lunar influence on ovulation.36

PUBERTY, MENARCHE, AND ADOLESCENCE

Puberty and adolescence have long been considered synonymous. They are, however, properly considered distinct entities with puberty defined as the sequence of physical, endocrine, and reproductive system changes that lead to the physical maturation of a girl into womanhood, and adolescence encompassing the psychological maturation that leads to readiness to assume adult responsibility.37 Menarche is the onset of the first menstrual period.

Puberty is classically divided into four distinct stages associated with landmarks in sexual development: (1) growth spurt, (2) thelarche, (3) adrenarche, and (4) menarche that in total extend over a period of approximately 4.5 years. It is triggered largely by genetics but also appears to be influenced by geography, level of light exposure, nutritional status, general health, and psychological factors.38 Body weight may be a significant factor in the onset of puberty, with girls who weigh more exhibiting earlier signs.

Adrenarche, the development of pubic hair, occurs prior to or concomitantly with thelarche, although in 20% of girls it precedes breast development. Initial hair growth is only slightly pigmented, sparse and fine, appearing on the labia majora. With maturation, the volume of hair growth increases and spreads to cover the mons pubis. The hair becomes more darkly pigmented, coarser, and less straight. After approximately 2 years, at which time axillary hair growth begins, the genital pubic hair achieves its characteristic curly appearance and is distributed triangularly with a horizontal border at the level of the pubic bone. Androgens are primarily responsible for hair growth. During these stages, vaginal acidity is increasing and there is an increase in the number of normal vaginal flora.

Menarche, the onset of menstruation, is the final stage in the process of puberty, and occurs at a mean age in the United States of 12.2 years for black Americans and 12.8 years for white Americans. Menarche typically occurs 1 to 3 years after the onset of breast development. Initial menstrual cycles are anovulatory, with anovulatory periods lasting from 12 to 18 months. Fifty percent of girls with early onset of menarche typically have established ovulatory cycles after 1 year, whereas girls with late onset ovulation often take 8 to 12 years for all cycles to become ovulatory.39 Menstrual cycles are typically variable for the first 2 to 3 years after menarche, but most cycles range from 21 to 45 days even in the first year of menstruation. Occasionally, cycles may be shorter or longer than this with no pathology. Menstrual bleeding generally lasts for 2 to 7 days. The individual’s own pattern of normal cycles is typically established by the sixth gynecologic year.39 The time leading up to menarche and the pubertal years is typically marked by varying levels emotional lability and behavioral changes, including “euphoria, depression, mood swings with paradoxical and hysterical reactions, crying with ease, and a negative attitude toward school.”40 Emotional and behavioral challenges usually taper off once the process of sexual maturation is completed and hormonal regulation is achieved.

SIGNIFICANCE OF AGE AT MENARCHE AND PATTERNS OF EARLY MENSTRUAL CYCLES ON LONG-TERM HEALTH

There has been media attention and concern given to the fact that girls appear to be entering puberty at earlier ages than historically. In fact, there is some disagreement in the literature as to whether this is the case. One author states that in white American females, the mean age of menarche has not changed in 50 years, although the author admits that population studies may obscure the actual rates, whereas others state that evidence from the United States points to a decline in the mean age of menarche from 14.7 years at the turn of the century to age 12.8 at the end of the twentieth century.39,41 These latter data are allegedly corroborated by European data that demonstrate a decline in age of menarche of 3 months per decade over the past 150 years.41 All authors agree that earlier menarche is noted in girls living in urban environments and relate this to heavier than average weight compared with cohorts in rural areas. Increased rates of obesity and exogenous estrogens may indeed play a significant role in the early onset of menarche, and in addition to the risks associated with being overweight, may have implications for increased adult rates of breast cancer development. In fact, early age at menarche (<12 years) is a recognized risk for breast cancer, with risk declining by 10% for each year after that in which menarche is delayed.41 This is primarily thought to be associated with greater cumulative exposure to estrogen and progesterone, especially estradiol. This risk may be reduced by the fact that girls who begin menstruating earlier are more likely to experience adolescent childbearing.

Conversely, girls with higher estrogen levels may be less predisposed to osteoporosis owing to increased bone density accumulation in the pubertal period, as evidenced by lower rates of osteoporosis among black women compared with white women. Adolescent girls with suppressed estrogen levels should be carefully monitored for bone density and optimally all girls should consume high-calcium diets or take calcium supplements particularly in the few years after menarche when bone density accumulation is as great as 10% to 20% and ensures as much as 10 to 20 years of protection against age-related bone mass loss.38

TALKING WITH GIRLS ABOUT MENSTRUAL HEALTH AND HYGIENE

Although our culture has certainly become more open about menstruation, with overt menstrual product advertisement or mention of PMS commonplace, many girls are still reticent when discussing the topic. Girls may be generally ignorant about what is happening to their bodies, and even the more knowledgeable girls may be uncertain about such things as maintaining menstrual health and hygiene.

A blood loss of 30 mL per cycle is considered normal, with a loss of greater than 80 mL considered abnormal, putting a girl at risk for anemia. However, there is little value in milliliter measurement as this is virtually impossible to calculate. More useful is keeping track of the number of menstrual pads changed daily and their level of saturation. Typically, a girl can expect to change her pad three to six times per day. If the pad is oversaturated, she might not be changing pads frequently enough, the pads may be of the wrong size or fit, or they may be slipping in her underwear. If after ruling out these factors, there is concern over excessive menstrual flow, evaluate further. Educating the girl about proper use of pads, how often to change them, and also about the different types of available products (e.g., tampons) and their use can help a girl to be more comfortable during her menses and also prevent the embarrassment that could come from overflowing a pad. Many girls, especially athletes, are curious about the use of tampons. This is an area in which education is particularly important. Although all tampons must now meet FDA regulatory limits on absorbency, 50% of all reported cases of TSS still occur in menstruating women. Current US FDA recommendations state that tampons should not be worn for 24 hours a day nor 7 days a week, and should be alternated with the use of pads.39 Tampons should be changed at least every 4 to 8 hours; it is preferable to sleep with a pad rather than a tampon, and the last tampon at the end of menses must be remembered—it is relatively common for a girl or women to forget to remove a tampon at the end of the period. TSS should be treated as an acute medical emergency.

EMOTIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL CHALLENGES IN ADOLESCENCE

Adolescence is a challenging and confusing time for even the most stable of girls. Hormonal changes and fluctuations, physical changes leading to the sexualization of the body combined with confusing cultural messages about the role of the adolescent and sex, increasing pressures at school and the challenges of teen friendships, and problems at home (stress with parents, birth of a sibling, trouble with a sibling, parents experiencing marital discord or divorce, financial troubles, moving to a new location/home/school, death of an elderly relative such as a grandparent, or personal illness) can lead to enormous internal turbulence. It is critically important for girls at this age to have women confidants they can turn to for security, advice, reassurance, and accurate information. An anchor in the storm may be the best thing a teenage girl can have to help her stay healthy and focused on self-development rather than getting side-tracked by the many distractions available to adolescents. And this anchor needs to be available as early into puberty as possible-access to drugs and sexual experience starts in middle school for many US children. Health care providers can also provide an anchor for adolescent girls. One study, conducted in the late 1980s, looked at the major topics that teenagers wanted to discuss with their physicians. The top concerns expressed were: sexually transmitted diseases, birth control, fear of cancer, self-image, self-confidence, sexual function, and sexual abuse, yet most doctors were found only to discuss the topic of menstruation.39

By charting their cycles, girls can begin to identify patterns in their mood fluctuations and how they are associated with their menstrual cycle. This can help them to recognize their emotions as cyclical changes related to hormones and not something inherently wrong with them. Teaching girls the value of good nutrition, particularly adequate protein and healthy carbohydrates combined with a good vitamin and mineral supplement, to keep sugar and caffeine consumption to a minimum, and to keep the blood sugar stable can reduce mood swings and show them that they have some control over their emotional lives. Adequate sleep (teenagers may require as much as 12 hours per day!) and moderate exercise are also important for keeping emotions level and can also support cognitive function. Journaling can be a useful tool for self-expression and may help girls to both record and vent some of the challenging emotions they feel and situations they face as they emerge into women. Finally, if emotional or behavioral conflicts are significant, girls may benefit from or require counseling, as might the family constellation. A healthy home life is an important stabilizing force as young girls emerge into women and sort through their own identity, personal and social roles, relationships, and responsibilities.

HERBS AND ADOLESCENT GIRLS: SAFE USE VERSUS WRONGFUL ADVERTISING

In 2000, a national advertising campaign was launched for an herbal product called Bloussant® Breast Enhancement Tablets. The fall 2001 issue of Teen Vogue and the September 2001 issue of Seventeen ran full and quarter-page ads, respectively, for this product. These advertisements feed into the already prevalent idea that bigger breast size is better that led nearly 4,000 females 18 and younger to have breast augmentation surgery in the year 2000 alone (representing 2% of all such surgeries that year), a 425% increase over 1997 rates. This represents a growing trend of misuse of herbal products by teenagers.42 Marketing of herbal products to teens has become increasingly popular, and teens are receptive to this marketing, many of them believing that natural means safer.43 In fact, the prevalence of use as determined by limited population surveys appears to mirror that of national use by adults with nearly have of all teens surveyed reporting CAM use, with the use of herbal products at approximately 12%. 43 44 45 Teens primarily appear to base their use on perceived parental or friend use, and primarily appear to use herbs without parental knowledge.45 Many are concurrently using other pharmacologically active substances, including medications, other herbal products, or recreational drugs or alcohol. Common conditions for which teens use herbal products include PMS, urinary tract infections (UTIs), obesity, pregnancy, and enhancement of athletic performance or stamina. Adolescent girls are more likely than boys to seek health care, including CAM therapies, although the rate of supplement use is higher for adolescent male athletes than their female athletic counterparts (29% vs. 12%).43

COMMON PROBLEMS OF PUBERTY AND MENSTRUATION IN ADOLESCENT FEMALES AND THEIR BOTANICAL TREATMENTS

Mood Changes

The Botanical Practitioner’s Perspective

Mood swings are common among adolescent girls and may be particularly prevalent in the week or days just prior to the onset of menstruation, not dissimilarly to PMS, or they may occur more frequently and unpredictably than monthly or cyclically. Frequently, girls start exhibiting mood swings as early as age 11, which many parents assume to simply be a behavioral problem rather than recognizing the beginning of hormonally mediated mood changes. Mood swings may be extreme, ranging from hysteria to euphoria in a matter of moments. Dramatic behavior is not uncommon. Girls also may find that their cognitive functioning is not as sharp, especially just prior to menstruation, making it more difficult to concentrate and perform in school, especially in the more linear subjects such as science and mathematics. Tests in school just prior to menstruation may be especially challenging for some girls. These emotional and cognitive changes are typically the result not only of hormonal influences but also of dietary inadequacies and sleep deficiency so common to adolescence. Declining blood sugar associated with hormonal changes along with inadequate consumption of high-quality protein and carbohydrates and an over-reliance on simple sugar for energy can lead to marked decline in mood and concentration. Inadequate rest as a result of staying up late at night and getting up early for school can exacerbate poor mood or concentration problems (also see Premenstrual Syndrome).

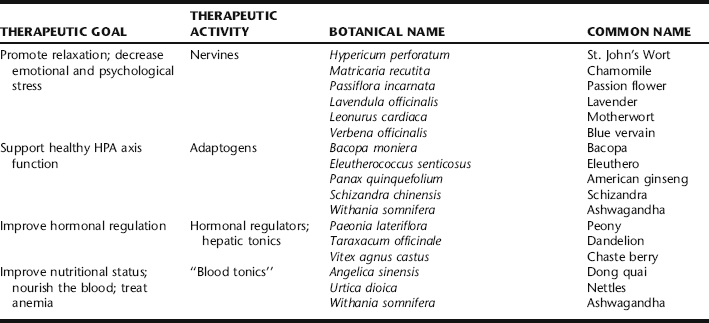

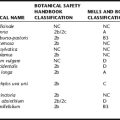

Adolescent girls are also subject to hormonal dysregulation that can lead to irritability, depression, and anxiety as frequently occurs with PMS. This period of time can be trying for parents and is difficult for the girl herself, who may be unhappy and feel out of control. Therefore, a great deal of support, encouragement, and reassurance may be needed as part of the health consultation. Conventional treatment relies on medication—either to regulate hormones, regulate mood (e.g., birth control pills, antidepressants) or both. In some cases medication may be appropriate, but counseling, lifestyle support, and appropriate nutritional and herbal supplements are preferable first line approaches when possible versus starting an adolescent on a course of hormonal or psychiatric drugs, whose long-term effects in the adolescent population are also frequently not well studied or understood. If depression is severe or thoughts or fears of suicide have been expressed, psychological counseling and medical intervention are essential. See Table 5-1 for a summary of mood changing herbs.

Discussion of Botanical Protocol

A number of herbs can be used to calm and nourish the nervous system. The gentlest of those that are used for promoting short- and long-term relaxation with a high safety profile when used in correct dosages include chamomile (Fig. 5-1), passion flower, and lavender, all of which are mild and nonaddictive. Ashwagandha is used over time as a tonic for the nervous system, and may exhibit beneficial effects on immunity, hemoglobin levels, and may have uterine antispasmodic activity as well, making it particularly beneficial when there is also dysmenorrhea. 46 47 48 49 For significant irritability and emotional lability many herbalists include the herbs motherwort or blue vervain in formulas. These bitter nervine herbs are applied in much the same principle as herbs for liver qi stagnation are applied in TCM with the understanding that herbs that improve the smooth functioning of the liver (possibly through liver detoxification mechanisms) have a regulatory effect on the female endocrine system. St. John’s wort is included when depression is a component of the emotional picture.50 Additionally, bacopa, reputed for its ability to enhance cognitive function and retain newly learned information, is used to improve concentration while dong quai is used in formulas, when there is anemia.49 Vitex is used when there is emotional lability associated with the menstrual cycle, particularly when there is also menstrual cycle irregularity.46 It has a high safety profile, with no contraindications reported in the German Commission E Monographs, although it is generally considered contraindicated for use during pregnancy. Bohnert considers simultaneous use with hormone therapy and oral contraceptives to be contraindicated. 46 47 48,51 In rare cases, short-term use of Vitex has been seen clinically to worsen depression; if this is observed discontinue its use immediately (Box 5-2).

| Chamomile | (Matricaria recutita) | 25 mL |

| Ashwagandha | (Withania somnifera) | 25 mL |

| Passion flower | (Passiflora incarnata) | 25 mL |

| Motherwort | (Leonurus cardiaca) | 20 mL |

| Lavender | (Lavendula officinalis) | 5 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

Dose: 5 mL twice daily or 2.5 mL as needed throughout the day not to exceed six doses.

Additional Therapies

Nutritional supplementation can play a pivotal role in the improvement of mood and cognitive function. In addition to taking a high-quality vitamin and mineral supplement (an adult dosage can be taken by girls 14 and over; younger girls can take a supplement designed for adolescents), adolescent girls can benefit from a high-quality essential fatty acid supplement containing both omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids. The best supplements contain a combination of both plant-based essential fatty acids (derived from evening primrose oil or borage oil) and cold water fish oil. Standard daily supplementation can improve mood and mental function, and can be helpful when skin problems are present (see Acne). Additionally, teenage girls who are menstruating need an adequate regular intake of dietary iron. If the diet is poor or there is heavy menstrual bleeding, dietary iron should be supplemented. Floradix® Iron and Herbs is an excellent and highly absorbable, nonconstipating iron supplement derived primarily from plant sources. It can be taken daily. Attention should be paid to adequate rest and opportunities for self-expression (journaling, art work) and physical activity to release tension (martial arts, running, swimming, boxing, yoga) (Box 5-3).

BOX 5-3 Treatment Summary for Adolescent Mood Changes

Dysmenorrhea in Adolescent Girls

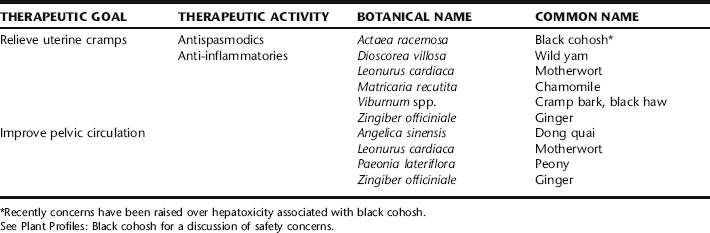

Cramping, and lower abdominal pain associated with the onset of menstruation, are the most common complaints of adolescent girls leading to missed days at school and self-medication with over-the-counter pain relievers and anti-inflammatory drugs and herbal products. In adolescents dysmenorrhea is generally nonpathologic and coincides with ovulatory menstruation, as progesterone secretion from the ovary is associated with uterine muscle contractility. It may coincide with or occur independently of PMS. Severe dysmenorrhea should be evaluated, particularly in sexually active girls, to rule out endometriosis, pelvic infection, or other problems (also see Dysmenorrhea).

Discussion of Botanical Protocol

Cramp bark and black haw can be used interchangeably as single herbs for the symptomatic relief of uterine cramps.52,53 Ginger is an antiinflammatory herb and traditionally used by herbalists for improving pelvic circulation.46, 54 55 56 It may be combined in tincture with other herbs or used alone beginning a few days before the expected menses and continued as needed. Dong quai also has demonstrated uterine antispasmodic activity.49,50 Excessive use of either ginger or dong quai may increase uterine bleeding; their use should be avoided if there is menorrhagia. Evening primrose oil is taken in capsules up to 1500 mg per day throughout the month or beginning in mid-cycle through the beginning of the menses. When there is significant cramping, peony, an excellent uterine antispasmodic, and motherwort might be added to the formula, the latter as uterine tonic and nervine antispasmodic (Box 5-4).49

BOX 5-4 Botanical Prescription for Adolescent Dysmenorrhea

A typical formula for an adolescent with dysmenorrhea is as follows:

| Cramp bark | (Viburnum opulus) | 55 mL |

| Chamomile | (Matricaria recutita) | 15 mL |

| Motherwort | (Leonurus cardiaca) | 15 mL |

| Ginger | (Zingiber officiniale) | 15 mL |

| Total: 100 mL |

Also: Evening Primrose Oil Capsules: 1000 mg daily

Additional Therapies

Increased arachidonic acid production is associated with increased inflammation and menstrual cramps. Reduction of red meat and dairy products in the diet may reduce the severity and frequency of menstrual cramps. Alternative sources of protein and calcium should be included in the diet to ensure adequate nutrition. Increased consumption of cold water fish such as salmon and supplementation with high-quality fish oil (often combined with evening primrose or borage oil) also may help in the reduction of inflammation and menstrual cramps. Supplementation with magnesium was demonstrated in an open study to help improve uterine muscle activity and reduce symptoms.53 Regular exercise with the addition of yoga poses for promoting pelvic circulation may be helpful. Abdominal massage, hot packs or ginger fomentations, and the use of hot baths with relaxing essential oils such as lavender, rose, and sandalwood can provide comfort and temporary symptomatic of menstrual cramps (Box 5-5).

BOX 5-5 Treatment Summary for Dysmenorrhea in Adolescent Girls

Menorrhagia in Adolescent Girls

Additional Therapies

Additionally, vitamin A deficiency has been found to be an important factor associated with menorrhagia. Vitamin A is a cofactor of 3 beta-dehydrogenase in steroidogenesis and deficiencies of this vitamin may result in impaired enzyme activity. The level of endogenous 17 beta-estradiol appears to be elevated with vitamin A therapy, and in one study, menorrhagia was alleviated in more than 92% of patients.57 Iron supplementation is essential because menorrhagia is regularly associated with anemia (Box 5-6).

BOX 5-6 Treatment Summary for Menorrhagia in Adolescents

Amenorrhea in Adolescent Girls

Adolescent girls may experience either primary or secondary amenorrhea. Primary amenorrhea is the lack of menses by age 16; secondary amenorrhea is cessation of menses for three cycles or 6 months in girls or women who have previously menstruated. Primary amenorrhea is specific to adolescent girls and has a broad range of possible causes requiring medical consultation.

Acne

Acne, often dismissed by the medical community as simply a consequence of adolescence, is actually the most common dermatologic condition, affecting at least 85% of all adolescents.58 It not only has the potential to cause permanent physical scarring but may have a significant effect on psychoemotional and social well-being and quality of life. Acne in adolescents and adult women is addressed in the next section.

ACNE VULGARIS

Acne vulgaris, acne, is a common and chronic skin condition affecting the pilosebaceous unit. It affects 80% of people in the United States at some point in life, and at any given time in the United States affects an estimated 17 million people.59 It is the most common dermatologic condition seen in clinical practice leading to more dermatologic visits than any other skin condition, and leading to absenteeism at school and work and to millions of dollars in annual treatment costs. 60 61 62 At least 85% of adolescents and young adults are affected by acne. Not only does severe acne potentially cause permanent physical scarring, it has a significant psychosocial impact on the sufferer, sometimes dramatically reducing quality of life, particularly, but not exclusively, in adolescent girls, where it can have a marked influence on self-esteem and lead to embarrassment, anger, anxiety, and depression. 63 64 65 66 Previously considered a condition of adolescence, it is now widely recognized to be a problem that can persist chronically or cyclically well into a woman’s fourth decade of life.67,68

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

During adolescence androgen levels increase, explaining the prevalence of acne during this time. However, elevated androgen levels are not always a finding; in 60% of women with acne, serum androgen levels are normal but there is significantly elevated 5α-reductase at the sebaceous gland, indicating a heightened sensitivity to androgen. This also may explain the persistent or recurrent acne that might occur well into a woman’s forties.72 Increased 5α-reductase results in higher rates of conversion of androgens, specifically conversion of testosterone into its active metabolite dihydrotestosterone.73 There is clearly an association between acne and menstruation with a premenstrual flare noted as common among 3394 women who completed a survey on the prevalence of acne in females in France.74 Emotional stresses have also been demonstrated to increase acne outbreaks. Additionally, hyperandrogenic conditions including polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), 21-hydroxylase deficiency, adrenal androgen excess, and some medications (e.g., steroids) are clearly implicated causes of acne.70,72,73,, 75 76 77 P. acnes converts sebum to free fatty acids and individuals who are hypersensitive to these free fatty acids may experience the more uncommon forms of severe nodular acne.73 Hyperinsulinemia also may play a role in the etiology of acne, evidenced by the increased glucose levels at the sebaceous gland of those with acne, and the prevalence of acne and PCOS in those with hyperinsulinemia, although a causal association is not conclusive.

DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis of acne is made upon visual inspection and exclusion of other causes. Acne may be dismissed as an unimportant consequence of adolescence or cyclic hormonal fluctuation; however, this may a gross underestimation of the significance of the problem.63 In a 1994 study conducted by the AMA, 89% of adolescent girls reported worrying about their complexion and 50% believed it was the first thing people noticed about them.78 Therefore, quick diagnosis and treatment from the time of onset of acne is important, particularly in the adolescent population when it tends to be the most severe and has the greatest social impact. Conventional therapy also calls for dermatologists to be adept at recognizing and treating resultant psychiatric disturbances in patients with acne.61 Furthermore, the appearance of acne may be indicative of more serious problems, such as PCOS, which predisposes to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular problems.77

CONVENTIONAL TREATMENT

Acne vulgaris is not considered a curable disease by conventional medicine; however, symptoms are frequently well controlled and scarring prevented by a combination of systemic (internal) and topical therapies, with patients typically prescribed a combination of therapies as suggested by the causes and severity of the case.60,79,80 Effective treatments are aimed at treating the four pathogenic factors mentioned in the preceding. Combination therapies are considered to be the most effective.60 However, in mild cases, topical treatment sometimes may be adequate.81

Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives have demonstrable effects in improving hormonally mediated acne, however, women are often concerned about their side effects. Additionally, teenage girls may be concerned about social perceptions related to their use of OCs, including disapproval or misunderstanding of the reasons for the medication.66 In addition to oral contraceptives, other androgen antagonists may be prescribed.76 For a complete discussion of the treatment of polycystic ovarian syndrome, refer to that section of this text.

Oral Antibiotics and Retinoid Preparations

In addition to OCs, systemic treatments for acne include the use of oral antibiotics and retinoid preparations.63,67,80,81 Isotretinoin is the only medication thus far to induce long-term, drug-free remission; however, its use internally has been clearly demonstrated to carry risks of teratogenicity. Therefore, it cannot be used during pregnancy and ongoing negative pregnancy tests should be obtained when women of childbearing age use this drug. Isotretinoin treatments for clearing acne have been associated with marked improvement in quality of life and psychological status in those with severe acne who have benefited from its use.6 Unfortunately, there has also been substantial concern in recent years regarding its association with increased suicide rates among users.63,81 Topical use is not associated with these risks and is considered effective and safe. Antibiotics can be effective at reducing inflammations however, antibiotic resistance is emerging as a new and important concern in their use as first line internal and topical therapies.69 Internal therapies are aimed at reducing microbial colonization, treating hyperkeratosis, and reducing immune modulated and inflammatory responses.70

Topical Treatments

Commonly prescribed topical treatments include retinoids, benzoyl peroxide, and antibiotics. Table 5-3 addresses the various systemic and topical treatments currently in use, their actions, and adverse effects. Conventional medical therapy for the treatment of acne vulgaris may need to be maintained for months or well over a year. This is limited by the tolerability of systemic and local dermatologic agents, the stigma to adolescents of OC use, the long-term risks of OC and corticosteroid use, limited ability to control sebum production with medications, development of antibiotic resistance by P. acnes, and in women of childbearing age, interference of antibiotics with OCs and demonstrated teratogenicity of the most effective moderate to severe acne therapy-isotretinoin.

TABLE 5-3 Common Pharmaceutical Approaches to Treating Acne63, 69 70 71

| PHARMACEUTICAL DRUG | ACTION/ADVERSE REACTIONS |

|---|---|

| Systemic Treatments | |

| Antibiotics: Tetracycline, Clarithromycin, Clindamycin, Doxycycline, Erythromycin | Reduce microbial colonization, anti-inflammatory for moderate to severe acne when topicals not adequate alone. Adverse effects of oral antibiotic use range from increased vaginal yeast infection, GI tract upset, and decreased efficacy of oral contraceptives due to decreased intestinal absorption of estrogens from gut microflora disruption, to antibiotic resistance, an increasingly prevalent problem. |

| Hormonal drugs: oral contraceptives/antiandrogen therapy |

Reverse hyperandrogenic states; reduce hormonal pathogenesis associated with acne by lowering levels of circulation androgens thus the only treatment effective at actually controlling sebum production. May also decrease adrenal and ovarian androgen production. Women using OCs are at risk for the well-documented common and serious adverse effects associated with their use. OCs containing androgenic progestins may aggravate acne.

|

| PHARMACEUTICAL DRUG | ACTION |

|---|---|

| Topical Treatments | |

| Tretinoin | A comedolytic agent; normalizes follicular keratinization; promotes drainage of existing comedones; prevents formation of new comedones; use may resultant in decreased inflammation. May take 3 to 4 months for improvement; can cause local irritation that may persist until after 3 weeks of use. |

| Topical antibiotics: Tetracycline, Clindamycin, Erythromycin | Treats mild to moderate inflammation; reduces bacterial colonization through chemotaxis suppression and reducing amount of free fatty acids in surface of skin. Local irritation can be a problem; topical use of clindamycin associated with severe GI reactions (including pain, bloody diarrhea, and colitis). Antibiotic resistance development is an increasing problem. |

| Benzoyl peroxide | Reduction of microbial colonization, anti-inflammatory activity; can cause local irritation, erythema, dryness, or allergic contact dermatitis. Also bleaches clothing and bed linens. |

| Azelaic acid | Treatment for mild to moderate acne. Bacteriocidal, bacteriostatic, anticomedonal, decreases keratinization of the hair follicle. Has a very favorable safety record with low rate of local adverse effects, and is appropriate for long-term use. No known interactions with other topical agents so may be effectively used in combination therapies. |

| Retinoids | Vitamin A derivatives and analogs, they reduce keratinization by interacting with retinoic receptors. They modulate cellular differentiation and inflammation. Local irritation is typical of topical retinoids. |

| Isotrexin (a combination of isotretinoin and erythromycin) | Reduces number of lesions and inflammation |

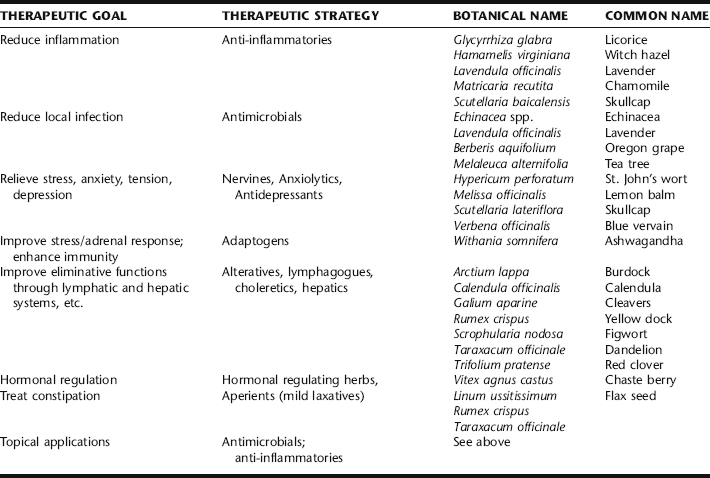

Botanical Treatment of Acne

Philosophical View

The botanical medicine practitioner takes a multifactorial approach by incorporating dietary and nutritional modifications, attention to the individual female’s hormonal patterns, and the effects of stress on and from acne into a comprehensive treatment plan. Supporting evidence below focuses on herbs that directly target the skin through anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, or hormonal effects. Table 5-4 provides suggestions for adjunct therapies that might be considered in conjunction with these direct acting agents, for example, the use of nervines or adaptogens.

It should be noted that immediate results are not expected when treating chronic acne. Improvement may take place over several weeks or longer, and when acne is associated with menstruation, over several cycles.

Discussion of Botanicals

Burdock Root: Internal/Topical

A comprehensive database search for uses of burdock root yields a long list of articles demonstrating its historical and traditional use for the treatment of sores, boils, and abscesses. It is discussed in King’s American Dispensatory as an alterative, aperient, and specific herb for impaired nutrition of the skin, specifically recommended for eczema, psoriasis, and dry scaly eruptions.82 Burdock root is used as an alterative and gentle laxative. The root extract has mild antibiotic activity, attributed to its polyacetylene constituents, which however, may not be present in commercially available dried material.83,84 According to Wichtl, the European use of burdock as an herbal drug is nearly obsolete. The German Commission E did not support its therapeutic use owing to insufficient evidence.85 No clinical studies using burdock have been identified in the literature. Nonetheless, it remains widely used by herbalists as a decoction or tincture to be taken internally for the treatment of skin conditions, including acne. However, there is controversy among herbalists about its efficacy for skin conditions, and some have reported exacerbations of inflammatory skin conditions. It is typically used internally, although it may be used topically as well.

Calendula: Internal/Topical

The effectiveness of calendula blossoms in the treatment of skin inflammations is well documented. Although the active principles have not been clearly defined, it contains both anti-inflammatory flavonoids and retinoids.83,85 Calendula, a bitter, cooling herb, exerts systemic antiseptic and anti-inflammatory activity when used orally, and is considered specific for the treatment of sebaceous cysts and acne.86,87 Limited uncontrolled studies on the antimicrobial activity of calendula have been conflicting, and tend to discount its efficacy, although it has demonstrated anti-inflammatory activity.88 Its demonstrated effects include promoting epithelialization of surgical wounds, and bactericidal action against S. aureus.32 Herbalists continue to rely on it, finding it highly effective clinically for skin inflammation and infection, used both internally as a decoction and topically as a wash, steam, or fomentation. It is considered specific when there are swollen lymph nodes, and used internally, is considered to promote lymphatic circulation and drainage.

Chamomile: Internal/Topical

Chamomile is indicated externally for treatment of inflammation of the skin and mucosa, used as a wash or steam. Its effects may be largely owing to the chamomile flavones, e.g., apigenin, that exert a local anti-inflammatory effect with topical application. Apigenin is not only adsorbed at the skin, but penetrates to deeper layers.83 Although no reports on the use of chamomile for the treatment of acne were identified, several reports indicate beneficial effects from topical use of standardized chamomile creams in the treatment of eczema, with two trials showing chamomile cream to have equal, or superior effects to topical steroidal and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.87,89,90 It is recommended in the German Commission E Monographs for inflammations and bacterial conditions of the skin. No studies were identified on its specific use for acne. Allergic irritating skin reactions have been reported with the use of chamomile flowers topically, but such reports are very rare.83 Internal use is appropriate as an adjunct treatment for stress and anxiety associated with acne.

Chaste Berry: Internal

Chaste berry is sometimes recommended for the treatment of acne, and in particular, menstrually or hormonally related skin problems.* Its use for acne appears partly based on a study conducted in 1968 by Giss and Rotheberg demonstrating clinical effectiveness in a group of 118 men and women (70% were women, some with PMS), including recurrence of acne with lapses in herbal treatment and complete healing in 70% of patients who had previously been unresponsive to long-term conventional therapy. Mills and Bone suggest the therapeutic efficacy seen in this study may be attributed to the mild antiandrogenic effects of Vitex, although this remains unknown.93 Low Dog, however, argues that it seems illogical to give chaste tree for the treatment of acne given that acne seems to be aggravated in the progesterone dominant luteal phase of the menstrual cycle when Vitex appears to increase LH and progesterone levels.90 Clearly, there is a great deal still not understood about the interactions of herbs with the endocrine system. Vitex has a good safety profile and may be of benefit in some women with acne; however, at this time there appears to be no scientific justification of its routine use as an acne treatment.

Chinese Skullcap: Internal/Topical

Scutellaria baicalensis, or “scute,” is considered specific in TCM for clearing “damp heat,” a category of diagnosis in which acne may commonly fall. It is clinically remarkable for reducing inflammation in dermatologic conditions and should be considered an important herb in formulations for treating acne and other skin conditions. It has also shown antimicrobial activity against a broad spectrum of microorganisms.91 It can be used orally for its systemic anti-inflammatory effects and/or topically in cream or wash form as a local anti-inflammatory (Fig. 5-2).

Cleavers: Internal

Cleavers is used internally for the treatment of a wide range of skin conditions.83,87 It is particularly indicated when there are enlarged lymph nodes, and for inflammatory, eruptive skin conditions.84 Its use is based on traditional evidence.

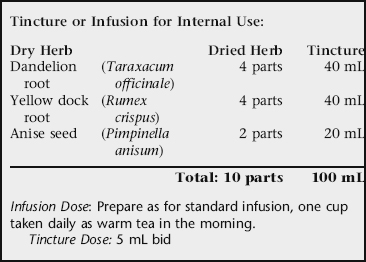

Dandelion Root: Internal

Dandelion root is an alterative and perhaps one of the best-regarded tonics for the liver.83 Traditionally, it has been included in formulae for skin conditions such as acne. No human clinical trials have been conducted to support the uses of dandelion root for skin conditions.90,92 Its use as a bitter, cholagogue, and aperient to promote and enhance liver function, bile secretion, and bowel elimination, respectively, may suggest some of the mechanisms of action in treating acne.

Echinacea: Internal/Topical

Echinacea has been used traditionally to clear inflammatory skin problems. It was used in the treatment of boils, abscesses, and eruptive skin conditions. Echinacea is believed to exert its benefits in the treatment of skin conditions via enhancing the activity of the lymph system, improving local elimination and reducing inflammation.93 Echinacea also may be applied locally (topically) for inflammatory skin conditions. The polysaccharides are being investigated as possible active ingredients in its external activity.83 Echinacea has demonstrated important immunomodulatory effects. It may be included in internal use formulae for chronic acne, as a general anti-inflammatory and immunotonic herb. Echinacea has been used successfully as a local anti-inflammatory for minor wounds and may be considered as part of a rinse or cream-based topical preparation.93

Figwort: Internal

Figwort, an herb not commonly known outside of herbal and naturopathic practitioners, is an alterative used specifically in the treatment of skin conditions, usually reserved for those that are intractable, aggressive, or longstanding.93 It is considered eliminative, having mild laxative, diuretic, as well as lymphatic activity. Hoffmann cites figwort as having cardiac stimulant activity, and cautions against its use in patients with tachycardia and those on cardiac glycosides, which it might potentiate.84 It is otherwise unexpected to cause side effects when used at the recommended dosage.

Guggul: Internal

Guggul (equivalent to 25 mg gugulsterone) was found to decrease the number of inflammatory acne lesions by 68% in a small, randomized study (n = 20), compared with 65.2% with tetracycline (500 mg). The response in inflammatory lesions (papules, pustules, nodules, cystic lesions) was better than that in noninflammatory lesions (comedones). It is thought that the antilipolytic activity of gugulsterones reduces the output of sebum and inhibits the lipolysis of triglycerides by bacteria to free fatty acids.94 The study design was not considered methodologically rigorous.95

Licorice: Internal

Licorice has demonstrated increased cortisol effects (primarily in ulcerative bowel conditions). 95 96 97 98 99 Glycyrrhizin, a saponin of licorice root, and its derivative, glycyrrhetinic acid (GA), have been found to inhibit 11-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, the enzyme that catalyzes conversion of cortisol to cortisone. One study found that 2% GA combined with hydrocortisone enhanced the local effects of the hydrocortisone. Because GA is already touted as a topical anti-inflammatory for dermatitis and psoriasis, this may point to a potential concomitant use of GA with hydrocortisone not only to enhance local effects but also to reduce systemic adverse effects with acne treatments.100 It is used by herbalists as part of internal formulae for the treatment of acne and other inflammatory skin conditions. Licorice has not been directly studied for its effects in the treatment of acne; however, it should be considered for patients who wish to switch from corticosteroid treatments to a more natural approach to acne treatment, which should be done under the supervision of an experienced practitioner.97

Oregon Grape Root: Internal/Topical

Oregon grape root has a long history of use for the treatment of a wide variety of chronic skin conditions, including acne, and was listed as a bitter tonic in the USP until 1916 and the National Formulary until 1947 as a bitter tonic, which as discussed, holds implications for its use in treating acne. One placebo-controlled clinical trial of nine male and female patients aged 12 to 30 years using a topical cream of 10% Oregon grape tincture in a 1:10 extract versus placebo, applied topically twice daily for 8 weeks, showed positive results with both groups demonstrating a reduction in skin oiliness and lesions, but only the Oregon grape group showing a decrease in sebum production. However, the study was considered too small and the preparation possibly too dilute to demonstrate a significant therapeutic effect. 101 102 103 Kraft lists Oregon grape as a primary treatment protocol for acne and seborrhea, citing its anti-inflammatory effects.104 Mitchell suggests that when thinking of Oregon grape, one should think of the skin-digestive system connection. He states that most cases of acne, eczema, and psoriasis are eased symptomatically by using this herb (Fig. 5-3).105

Tea Tree: Topical

Tea tree oil is a popular external application for skin problems. It has antibacterial and antifungal activity, in vivo, against a number of organisms, although its antiviral activities have not been conclusively demonstrated. A randomized control trial (RCT) of a 5% tea tree oil lotion demonstrated effectiveness as a topical antiseptic in the treatment of acne, slightly less effective than benzoyl peroxide in treating acne, although with fewer side effects. One hundred twenty-four patients were randomized to receive either tea tree oil or 5% benzoyl peroxide lotion for 3 months. Both groups showed improvement in the number of inflamed lesions, the number of non-inflamed lesions, and skin oiliness. Side effects in the tea tree group included skin dryness, pruritus, stinging, burning, and redness.83,106 The German Commission E Monographs include skin inflammations and wound healing as indications for its use.85 As with other essential oils, allergic dermatitis is a common side effect of tea tree oil, both from direct application to the skin (contact), as well as from inhalation of the vapors and ingestion.83,102 Skin irritation appears to increase with the age of the tea tree product, possibly as a result of oxidation products, thus product freshness and storage practices may influence the rates of dermatitis.102

Witch Hazel: Topical

The astringent and anti-inflammatory herb witch hazel has been used successfully for the treatment of dermatological conditions (inflammation and eczema) and may be used topically as a facial wash or in a cream base. Witch hazel distillate has demonstrated noteworthy effects in the treatment of topical inflammation after UV exposures, and witch hazel creams and ointments have shown anti-inflammatory effects in patients suffering from atopic neurodermatitis, psoriasis, and eczema in a total of six different clinical trials.99

Differential Topical Treatment: Dry vs. Oily Skin

Practitioners must be sensitive to the skin type and preferences of individual patients when choosing topical medications.69 Agents containing a higher volume of alcohol may be preferable to patients with oily skin and drying to those whose skin is already dry. Conversely, patients with dry skin may prefer moisturizing bases such as creams, ointments, or oils.

Facial Steams

Hot facial steams are helpful for opening the pores and allowing delivery of antiseptic volatile oils to the affected areas. The patient is instructed to bring a large pot of water to a boil, and while doing so have ready a large bath towel, the necessary essential oils, and a trivet. The trivet is placed in a sink and when the water comes to a boil, the pot is placed on it. The lid is quickly opened and three to five drops of essential oil are added and the lid quickly replaced. The patient is then to form a small tent over the head and sink and carefully remove the lid allowing the steam to bathe the face. The face should be kept at least 18 inches from the pot and care must be taken to avoid burning from the steam. The steam exposure should be maintained for 3 minutes, after which the patient should rinse the face with cool water or an astringent herbal infusion (e.g., witch hazel distillate). Lavender, tea tree, and rosemary essential oils are all excellent antimicrobials and may be used alone or in combination. This treatment can be repeated several times weekly, and may be accompanied by systemic treatment. Herbalists often use lavender as a mild soothing topical antiseptic. Although no clinical trials using the extract or flowers have been identified, its aromatic nature enhances topical applications and inhalation of the essential oil has been shown to induce relaxation.85,87 Witch hazel may be used as a cool rinse after the steam to tonify the pores. Additionally, the steam water can be substituted with an infusion of any number of botanicals for the skin including a combination of the antiseptic and anti-inflammatory herbs: calendula, chamomile, lavender, and witch hazel to which the essential oils are added.

Botanical Formulae for Acne

BOX 5-7 Botanical Prescription for Acne vulgaris

Tincture for Internal Use

| Chinese skullcap | (Scutellaria baicalensis) | 20 mL |

| Oregon grape | (Berberis aquifolium) | 10 mL |

| Echinacea | (Echinacea spp.) | 20 mL |

| Dandelion | (Taraxacum officinale) | 20 mL |

| Licorice | (Glycyrrhiza glabra) | 20 mL |

| Ashwagandha | (Withania somnifera) | 10 mL |

| Total: 100 mL | ||

BOX 5-8 “Alterative” Prescription for Treating Acne