Chapter 36 Menstrual Cycle–Influenced Disorders∗

The human menstrual cycle is unique as a physiologic process in that it involves mechanisms that change on a daily basis rather than remaining stable. This process of change is carried out through the many intricate hormonal interactions between the hypothalamic region of the brain, the pituitary gland, the ovaries, and to some extent, the adrenal glands and the pancreatic islets of Langerhans (see Chapter 4). To a large degree, the subject matter of reproductive endocrinology deals with disturbances of this interglandular hormonal communication that may result in irregular or absent menstrual cycles.

Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

Premenstrual Syndrome and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder

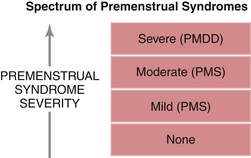

The acronyms PMS for premenstrual syndrome and PMDD for premenstrual dysphoric disorder refer to the same pathologic process at opposite ends of the symptom spectrum (Figure 36-1). In both PMS and PMDD, patients experience adverse physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. There is a crescendo of symptom intensity up to the time that menses begins, with quick resolution thereafter. Some patients have a brief surge of symptoms at the time of ovulation in midcycle.

FIGURE 36-1 Spectrum of premenstrual syndromes. PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder; PMS, premenstrual syndrome.

A formal set of diagnostic criteria has been proposed in the fourth text revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) of the American Psychiatric Association for PMDD (Table 36-1). Although the DSM-IV definition of PMDD specifies that this is not just an exacerbation of another disorder, the dividing line between PMDD and other neuropsychiatric disorders is not so clear cut. For example, 46% of PMDD patients have a history of a prior major depressive episode. Moreover, patients with PMDD and clinical depression share similar sleep electroencephalogram alterations, and they are both responsive to the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants.

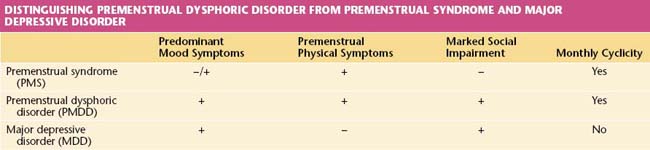

The physiologic mechanism that results in the occurrence of PMS and PMDD is not well understood. Evidence exists that the phenomenon arises, in part, from atypical metabolism of progesterone that results in lower levels of the steroid allopregnenolone within the central nervous system. Allopregnenolone is a neuroactive progesterone metabolite that modulates central gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors that modify behavior, emotion, subjective perceptions, and response to stress. In addition, the GABA and serotoninergic neurons may be inherently dysfunctional in PMS and PMDD patients, especially in those with severe depressive symptoms—hence the overlap between PMDD and clinical depression. Major depressive disorder (MDD) persists, however, on a daily basis for weeks without a relationship to the menstrual cycle. MDD, which usually does not have premenstrual physical symptoms, may however be exacerbated during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. In such cases, both PMDD and MDD need to be treated (Table 36-2).

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Practice Bulletin on Premenstrual Syndrome, No. 15. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2000.

Case A.M., Reid R.L. Menstrual cycle effects on common medical conditions. Compr Ther. 2000;27:65-71.

Kessel B. Premenstrual syndrome: Advances in diagnosis and treatment. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:625-631.

Rapkin A., Mikacich J. Premenstrual syndrome: Gynaecology or psychiatry? Reprod Med Rev. 2001;9:223-239.

Stotland N.L. Premenstrual syndrome. In: Berek J.S., editor. Berek and Novak’s Gynecology. 14th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:358-366.

Treatment

Treatment Menstrual Migraine Headaches

Menstrual Migraine Headaches Catamenial (Monthly) Epilepsy

Catamenial (Monthly) Epilepsy Other Menstrual Cycle–Influenced Disorders

Other Menstrual Cycle–Influenced Disorders Other Conditions

Other Conditions