chapter 48 Men’s health

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Despite the significant advances in healthcare of this century and the previous, men still have poorer health outcomes than women—an example is the current average male life expectancy of 78 years, compared to 83 for females.1 GPs regularly see male patients ignoring warning symptoms, denying health problems and dying prematurely from heart disease and cancer. Statistics show that, compared with females, males in the 25–64 year age group have four times the risk of dying from heart disease, twice the risk of dying from cancer and three times the risk of dying from alcoholic liver disease.

REGULAR SERVICE PREVENTS BREAKDOWNS

Men confront a number of challenges and barriers in being more proactive about their health. First, self-awareness and self-care are often not cultivated by men as much as women, and are not part of the traditional male culture. Images of male resilience and strength are more commonly inflexible and independent. Men also tend to be very career focused, in such a way that taking time off for ‘non-essential’ or ‘non-urgent’ things like GP consultations does not rate highly on the priority list unless the health matter cannot be ignored. Even then, denial is more common among men. Or men can avoid going to the doctor because they find talking about personal issues or vulnerability a lot more difficult than women do, particularly when those issues are of an emotional nature, regarding relationships, for example, or depression or anxiety. Self-medicating for such problems is an important part of the reason that substance abuse is more common among men. Many men may have a preference for consulting a GP of a particular gender. For example, some men may prefer to discuss emotional issues with women, or relationship or sexual issues with an experienced male practitioner. Often when a man presents with psychological and emotional concerns, he may want to approach the problem in a different way than a woman would—for example, a woman (and female practitioner) may wish to discuss the emotions and issues at greater length, whereas the man may want to discuss more direct and pragmatic solutions to dealing with the ‘problem’, whatever that may be. Being flexible in consulting style, or knowing how to open up discussion about emotional issues in a non-confronting way, may be an important skill for the healthcare practitioner to have in dealing with health matters for men. Furthermore, women tend to more often take the children and other family members to the doctor for appointments and so will more commonly establish a stronger link with healthcare practitioners and clinics, or are reminded about personal health issues while there. Women’s greater role than men in nurturing and caring is partly due to nature (biological and hormonal) and partly due to nurture (culture and upbringing). Therefore, confronting the barriers to men being more active participants in their own healthcare requires not only a healthcare practitioner who is sensitive to the consulting issues and psychology of men, but also a change of societal images of manhood.2

Ideally, health checks should be performed regularly through childhood, adolescence and adulthood (see Ch 17, The general check-up)—once men become familiar with the concept of being proactive rather than reactive, the GP can schedule a long consultation and perform the same comprehensive check-up, directed to conditions relevant to the age of the man, for older and younger patients.

Because most people remember their own birthdays, a useful method is to encourage patients to come for their check-up during the month of their birthday. As a minimum, in addition to a basic clinical examination (with or without a prostate check), they should have their weight, girth and blood pressure measured, plus blood tests for glucose, lipids and liver function. Based on the results, further examinations and investigations may be indicated. More likely is the situation where the results of the tests provide an opportunity for health education and counselling about appropriate lifestyle interventions—for example, practical steps that could be taken if their cholesterol or blood pressure is outside the expected range.

ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION

Erectile dysfunction is discussed in detail in Ch 49, Erectile dysfunction.

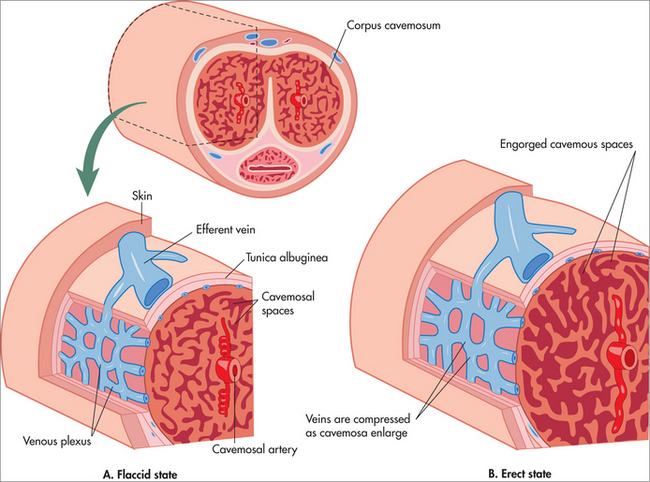

The strong association of ED with a diseased cardiovascular system is easy to understand if one appreciates that the inadequacy of blood flow in the penile arteries is simply a manifestation of what is happening in other similar-sized blood vessels. This explains why ED is more common in patients with conditions such as hypertension, high cholesterol, diabetes and ischaemic heart disease. Although ED is a common cause of emotional stress and relationship issues, one should also remember that stress and relationship issues are also common causes or exacerbating factors for ED. A significant finding by Thompson and colleagues was that men diagnosed with ED at the start of their study who were followed over 9 years had a higher incidence of heart attacks and strokes than a control population.3

ED can present to GPs in one of two ways:

In the case of the former, it is important to confirm that the symptoms are actually caused by ED rather than low libido, premature ejaculation or relationship difficulties, and to ensure that the dysfunction is not caused by undue anxiety to perform. Using the IIEF-5 questionnaire4 (described in Ch 49) can be useful in helping to ascertain whether the patient’s problem really is ED.

The management of ED is discussed at length in Ch 49. The important message here is that ED is common, can be effectively and easily treated in the majority of men, and may be the first symptom indicating more generalised serious disease.

TESTICULAR CANCER

Identified risk factors include:

If a man is suspected to have a cancer in his testis, it is mandatory to perform an ultrasound scan, which can usually differentiate a solid (cancer) from a cystic (benign) swelling. Such a patient should undergo thorough clinical examination as well as CT scans for features of metastatic cancer in the retroperitoneal nodes and lungs. The basic management of the primary tumour is orchidectomy through an inguinal incision.

PROSTATE DISEASE

The term benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH) is used to denote the pathological condition, while bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) describes the clinical syndrome, which may also be caused by other conditions such as bladder neck hypertrophy or urethral stricture. BPH was originally and impractically defined histopathologically as ‘a prostate larger than 20 g plus either elevated symptom score or reduced peak flow’, although no single definition has gained universal acceptance.5

Fifty per cent of men aged over 60 years suffer from BPH.6 We now know that BPH is not necessarily progressive; symptoms stay the same or regress spontaneously in at least half these men. Moreover, the impact of the symptoms is variable, and although there is a small risk of acute retention, in many cases all the GP need provide is reassurance, together with periodic monitoring of symptoms.

PROSTATE CANCER

Prostate cancer is discussed in detail in Ch 50, An integrative approach to prostate cancer.

At present, measurement of serum PSA (prostate-specific antigen) is combined with a rectal examination—PR (per rectum) or DRE (digital rectal examination)—to feel for nodules in the prostate gland. PSA is a glycoprotein produced by the normal prostate gland, and is normally present at very low levels in the blood. Prostate cancer cells produce increased amounts of PSA, so an increase in the level of PSA in the blood is suggestive (although not diagnostic) of prostate cancer. Twenty per cent of prostate cancers do not produce an elevated PSA, so both components (blood test for PSA as well as DRE) are essential. It is also important to note the age-specific ranges for normal PSA, as the previously accepted ‘cut-off point’ of 4.0 ng/L is no longer accurate. (See Ch 50 for discussion of PSA levels.)

SUMMARY

It is only recently that we as doctors have come to realise that men suffer a considerable degree of morbidity as well as mortality from andrological causes. Awareness of the unique health needs of men and cognisance of the latest information about the management of these conditions, as well as community education to encourage men to consult their doctors for preventive healthcare as well as when they develop symptoms, will go a long way towards improving male health in the twenty-first century.

1 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Deaths Australia, 2004. ABS (2005) Cat. No. 3302.0. Canberra.

2 Malcher G. Engaging men in health care. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(3):92-95.

3 Thompson IM, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, et al. Erectile dysfunction and subsequent cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2005;294:2996-3002.

4 Rosen RC, Cappelleri JC, Smith MD, et al. Development and evaluation of an abridged, 5-item version of the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5) as a diagnostic tool for erectile dysfunction. Int J Impot Res. 1999;11:319-326.

5 Walsh PC. Editorial: treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:587.

6 Kooner R, Stricker P. Benign prostatic hyperplasia. Med Today. 2000;1:317-324.