chapter 53 Menopause

DEFINING THE MENOPAUSE TRANSITION

Over the past two decades there has been much discussion about defining the terminology surrounding the last period. Sherry Sherman has aptly summarised some of the terminology, drawing together the WHO and International Menopause Society (IMS) recommendations (Box 53.1).1

BOX 53.1 Menopause terminology

Source: adapted from Sherman 20051

EPIDEMIOLOGY

In Western countries, the average age at FMP is 51 years, with a normal range of 40–60 years.2 The four or five years leading up to the FMP are characterised by menstrual irregularity, often initially cycle shortening, followed by cycle lengthening, although there is much normal variability. There are some minor variations in cycle patterns across different cultures but, as will be discussed later, quite marked differences in the symptoms are experienced across the menopause transition.

SYMPTOMS

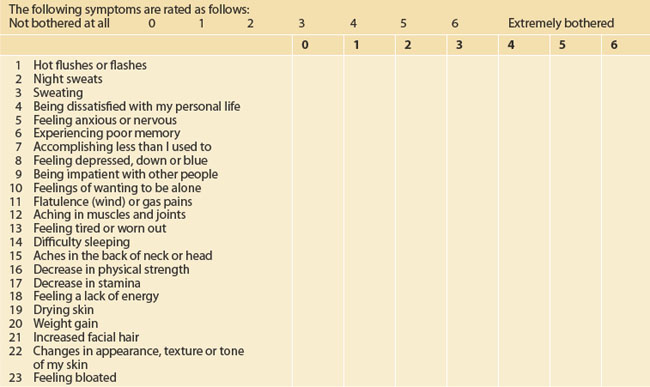

Some of the symptoms experienced by women in the menopause transition are listed in Box 53.2.

BOX 53.2 Symptoms that might be due to the menopause transition

The Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project is a prospective, longitudinal study of healthy women passing through the menopause transition.3 The study began in 1991 and used random telephone dialling to recruit Australian-born women aged 45 to 55 years. One hundred and seventy-two women were premenopausal at the time at baseline, and by the end of the seventh year of annual follow-up had advanced to the peri- or postmenopausal interval.

CULTURAL DIFFERENCES

There appear to be marked cultural differences in attitudes to menopause. In a study of Sydney women, Asian women generally appeared to view menopause in a more favourable light than Western women, who linked menopause with ‘getting older’. Asian women were also less likely to admit to a healthcare professional that they were suffering from vaginal dryness, but if a doctor raised the issue, they were very grateful.4,5

Among Indian women, only 34% complained of hot flushes; more were concerned about depression and memory loss.6 Unemployment was associated with more flushing and depression. Lebanese Muslim women reported high rates of feeling tired and worn out, as well as aches and pains, as they went through the menopause transition.7 Sixty-three per cent reported hot flushes and more than half had noticed vaginal dryness during intercourse.

Chinese women largely see menopause as a natural process.8 A group of Sydney-based Chinese women had more vasomotor symptoms (34%) than those women who live in mainland China (10.5%) or in Hong Kong (10–20%). The top three symptoms reported by Sydney-based Chinese women were poor memory (76.4%), dry skin (69.1%) and aching in muscles and joints (68.3%). Some told the interviewers that their vaginal dryness problem was so severe that they had given their husbands permission to have sex with someone else.

Among Greek women, most were more concerned about back pain, aches, pains and fatigue than about hot flushes.9 Seventy-nine per cent of the postmenopausal Greek women had vaginal dryness, and there was a high rate of sexual problems.

THE MENOPAUSE CONSULTATION

HISTORY

The initial menopause consultation is a long session and often takes at least 30 minutes. It might be facilitated by some pre-reading and by using one of the many menopause-scoring charts that are available, such as the MENQOL (Menopause-specific Quality of Life Questionnaire, Table 53.1).10

The following should be particularly considered while taking a ‘menopause’ history:

TESTS

All that flushes is not menopause. Consider the differential diagnosis of ‘night sweats’ (see below) including viral infection, tuberculosis, neoplasm, hyperthyroidism, sleep apnoea, gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, alcohol excess and hypoglycaemia.12

If early menopause is suspected in a woman under 30 years of age, it might be prudent to measure her FSH levels three times over 2–3 months. In this way, the diagnosis is usually readily confirmed. Antimüllerian hormone (AMH) is a relatively new blood test that may give some information on ovarian reserve.

MANAGING MENOPAUSE

LIFESTYLE ISSUES: THE ESSENCE MODEL

Exercise

Regular exercise is particularly important during and after menopause, not only to help manage symptoms but also to help prevent a range of chronic conditions such as heart disease, cancer, dementia and osteoporosis. Regular moderate activity will help weight management and can help to improve sleep and maintain mental and physical vitality and performance in menopausal women.13,14 Vigorous aerobic exercise can precipitate hot flushes, in some women.

MANAGING HOT FLUSHES

In Western culture, the most common menopause symptom is the hot flush (referred to as ‘hot flash’ in American literature). This typically begins as a feeling of intense heat in the chest and neck which soon rushes up over the head and then over the rest of the body. It lasts a few minutes and might be associated with feelings of nausea, palpitations, dizziness and formication. The sufferer usually goes bright red and ends up with a drenching sweat, often followed by chills and shivering. The menopausal hot flush can be extremely unpleasant. The frequency varies considerably, from 1–2 a day to 10–20 an hour, day and night. During the flush, central temperature does not rise, but skin temperature goes up by 5–7°C.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The menopause flush is caused by disruption of the thermoregulatory system in the anterior hypohalamus.15 Basically, there are two ‘thermostats’: if core temperature goes above the high one, flushes occur; and if core temperature goes below the lower thermostat, shivering happens. For those with severe vasomotor symptoms, the two thermostats are close together, and thus sweating and shivering are more easily triggered in these women. Neurotransmitters such as serotonin and noradrenaline are involved, which, as we shall see shortly, has implications for therapy.

LIFESTYLE MODIFICATIONS

Avoidance of triggers can be helpful for some. Such triggers include stress, hot drinks, spicy foods, alcohol, over-heating and hot weather. There is some evidence that a diet high in soy and cereal can help those with mild flushes.16 Vigorous exercise can make flushes worse by overheating the body.

HERBAL

Most of the over-the-counter herbal therapies either have been shown not to be more effective than placebo or have not been formally tested.17 Sage (Salvia officinalis), dong quai (Angelica sinensis), red clover (Trifolium pratense), Asian ginseng (Panax ginseng) and kudzu (Pueraria lobata) are commonly recommended, but evidence for their effectiveness is lacking.

Nelson and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of non-hormonal therapies for menopausal hot flushes.18 They found that red clover extracts were no more effective than placebo but that there was some evidence that some soy extracts are effective (e.g. Phyto Soya®).

By far the most effective and tested herbal is a standardised extract of black cohosh. It has been submitted to several randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Osmers and colleagues performed a RCT of 304 women randomised to two tablets a day versus placebo.19 The active treatment was statistically significant for a global menopause score and specifically for vasomotor, mood and vaginal symptoms, despite the fact that the extract is not oestrogenic.

Uebelhack and colleagues performed a RCT of black cohosh and St John’s wort extract among 301 women.20 Again the active compound was found to be superior to placebo for vasomotor and mood symptoms. St John’s wort can be combined with black cohosh. Palacio and colleagues reviewed trials of black cohosh.21 Most placebo-controlled trials showed that black cohosh was superior to placebo and equivalent to low-dose HRT and even tibolone. One trial even compared black cohosh with fluoxetine 40 mg and found that black cohosh was better for flushes and fluoxetine superior for moods.

Trials with black cohosh extracts have largely found no greater risk of side effects than placebo. However, there have been case reports of hepatic failure, probably autoimmune and idiosyncratic, associated with black cohosh. The incidence appears to be less than 1 in 100,000 cases.

OTHER COMPLEMENTARY AND ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Nedrow and colleagues have systematically reviewed complementary and alternative medicines (CAMs) used for menopausal symptoms.22 It can be challenging to design placebo for physical CAMs such as reflexology and acupuncture, but some researchers have managed to do so. One trial compared reflexology and ‘routine’ foot massage; and four trials used sham acupuncture needles. None of these treatments was found to be superior to sham treatment for the relief of menopausal symptoms. Nedrow and colleagues also reviewed six RCTs of Chinese herbal mixtures—all the RCTs were negative.

Slow, deep breathing—‘paced respiration’—can reduce the severity of a hot flush.15

NON-HORMONAL DRUGS FOR FLUSHES

HORMONE THERAPY

For the interested reader, Blake2 and Grady15 have recently reviewed the evidence base for managing menopause. HT has been around for a very long time—oestradiol implants since the mid-1930s and Premarin® (conjugated oestrogens) since 1942.

In Grady’s review, she demonstrates that 0.625 mg Premarin® and 1–2 mg E2 orally reduce hot flushes by around 90–95%, with a placebo effect of 45%.15 Relief is usually substantial within 4 weeks. Lower doses (e.g. 1 mg E2 daily) take longer to work but have a lower rate of side effects. Progestins are added to prevent endometrial hyperplasia. These are given either cyclically for 10–14 days or continuously, on a daily basis.

Using hormone therapy

The healthy perimenopausal woman seeking HT usually begins with a cyclical HT. Continuous HT does not suppress the cycle, and so breakthrough bleeding is common and can be troublesome. A short course of a low-dose OCP might be considered for a healthy, non-smoking, non-migrainous, normotensive woman under 50 years of age.

Risks and benefits of long-term hormone therapy

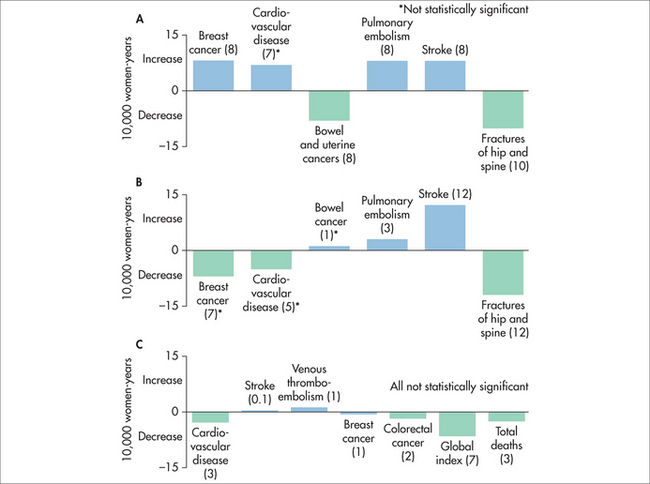

The WHI was an NIH-funded study into strategies to help older women. It had two HT arms, both tested in women whose average age was late sixties. The combined HT arm (Premarin®–Provera®) has been summarised by MacLennan (Table 53.2 and Figure 53.1).23

TABLE 53.2 Risks and benefits of combined hormone therapy in older women*

| Adverse effects | Benefits |

|---|---|

* Risk and benefits after 5 years of combined HT (compared with placebo). All rates are per 10,000 women per year.

** Not statistically significant.

When the WHI data were re-analysed in 2007, to examine risks in the usual age group who take HT—those aged under 60 years—no increased risks were found.23 It was disappointing that the authors took 5 years to release these data, and unfortunately this important message has not reached the general community. MacLennan also points out that there are emerging data that side effects are reduced by using lower HT doses, minimising systemic progestin exposure by using a Mirena® device, using non-oral HT in some women and initiating HT near menopause.

Several studies have examined the population rates of breast cancer since the decline in HRT use following the release of the WHI data. Breast cancer incidence decline and decreased HRT use showed a high correlation. The decline of breast cancer incidence started about 2 years after the HRT decline.24

The woman who has had a hysterectomy

The woman who has had a hysterectomy and who makes an informed decision to take HT should be treated with oestrogen only. The oestrogen-only arm of the WHI (Premarin® 0.625 mg daily versus placebo) enrolled 10,739 women aged 50–79 years and continued the trial for 7 years. The risk of breast cancer was decreased in the Premarin® arm and a non-significant increased risk of stroke was demonstrated.25,26 There is some evidence of decreased risk of thrombosis with transdermal oestrogen.2,15

Tibolone

Tibolone is not a traditional HT, but a steroid with oestrogenic, progestational and androgenic actions. Its effect on a target tissue depends on its final metabolism. For example, the endometrium converts tibolone to a progestational metabolite. When given to postmenopausal women, it has a lower rate of breakthrough bleeding and breast pain than standard HT and appears to have no impact on mammographic density, unlike HT, which usually increases breast density.2,15,23 However, weight gain is a common side effect and this tends to limit its appeal.

A randomised placebo-controlled trial of tibolone 1.25 mg (4538 women aged 60–85 years) was published in 2008.27 Women receiving the active treatment had significantly fewer vertebral and non-vertebral fractures and less breast and bowel cancer than the placebo group. However, the tibolone group had a doubled risk of stroke.

The LIBERATE trial28 randomised 3148 women with breast cancer to tibolone 2.5 mg or placebo. Fifty-eight per cent were node positive, 71% were oestrogen receptor (ER) positive, 67% used tamoxifen and 7% used aromatase inhibitors. Tibolone improved vasomotor symptoms and bone density in this cohort but, unfortunately, it was also associated with an increased risk of metastases. Therefore, tibolone cannot be recommended for women who have had breast cancer.

MANAGING THE WOMAN WHO FLUSHES FOREVER

If a patient is still having significant flushes after 5–6 years, she is probably in the small group who flush forever.2 Properly counselled, some of these women will persist with non-pharmacological methods of coping with the symptoms and some will choose to stay on low-dose HT—at least until a better choice is available—and accept the small risks. Theoretically, it may be appropriate to treat these women with transdermal oestrogen (e.g. a dot-patch) to minimise the risk of thrombosis, and consideration should be given to fitting her with a Mirena® device to minimise systemic progestin exposure. However, it should be pointed out that, at the moment, there is no evidence to support such an approach—and there will probably never be such data available.

DEPRESSION AND MENOPAUSE

Feeling sad or blue is a common symptom of menopause, affecting 19–29%, but studies have shown that clinical depression per se is not more common at menopause,2 except perhaps for those who have longstanding depression/anxiety. CBT and St John’s wort may assist with mood stabilising. HT might help stabilise the mood of some symptomatic perimenopausal women, but not those who are postmenopausal and flush-free.2

MANAGING GENITOURINARY SYMPTOMS

These symptoms can be managed by the use of non-hormonal moisturisers such as Replens®, avoiding soap (and instead washing with soap-free washes or sorbolene) and the use of lubricants. However, for some the symptoms are so severe that the only real option is oestrogen therapy. Rather than giving HT, topical oestrogens can be tried.15 There is scant long-term safety data on these products, but there is probably some minimal absorption in the first few weeks of usage while the vaginal epithelium is thin, but little absorption after that.

Continence training with an experienced continence therapist can assist bladder control.

Unfortunately, no CAM has been shown to help genitourinary symptoms.

THE ROLE OF ANDROGENS FOR WOMEN

Testosterone is more abundant in female serum than oestrogen, and serum testosterone levels appear to fall with age, not menopause, unless the ovaries are removed. In blood, testosterone is avidly bound to sex-hormone-binding globulin (SHBG) and only the small ‘free’ fraction is biologically active. Normally, the postmenopausal ovary continues to produce some androgens.2 Population studies have failed to link a decline in sexual activity with serum androgen levels. There are also technical problems with the measurement of testosterone. The commercially available assays are designed for the male normal range and not accurate for women or children. In some laboratories, a ‘sensitive testosterone’ assay is available, but even these have poor correlation with sexual desire and responsiveness. Clinical trials have been more helpful than laboratory-based studies.

Oestrogen therapy has been shown to improve vaginal lubrication; even oral HT, despite its adverse effects on SHBG (oral oestrogens increase SHBG levels and so lower free, bioactive testosterone levels), has been shown to improve sexual desire and arousal.2 There have been several RCTs of transdermal testosterone for women, usually as patches. In most of the trials, women received adequate oestrogenisation first. These studies have shown a significant improvement in sexual desire and more satisfying sex than placebo. Although serum testosterone levels are of no value in diagnosing hypoactive sexual disorders, they are useful in ensuring that patients are not over-treated, so that androgenic side effects can be minimised. Panay and colleagues published a trial using testosterone patches designed for women without oestrogen replacement, and showed a statistically beneficial effect on sexual desire with minimal side effects.29 It is important to explore possible reasons for low libido before reaching for the prescription pad. These might include relationship problems, emotional issues, over-commitment to responsibilities, and more.

BIO-IDENTICAL HT

Cirigliano has reviewed the scant medical literature on these products.30 These treatments do not undergo stringent quality control, their pharmacokinetics are largely unknown and there are no medium- or long-term safety studies. Often these expensive treatments are monitored using salivary and blood hormone levels that have not been validated.30 It is well known in clinical practice that, unlike monitoring thyroid function, where blood tests are exquisitely sensitive and useful, as already discussed, many of the main symptoms of menopause relate to the brain, rather than blood levels of any particular hormone.

Three cases of uterine cancer were described in Australian women using troches.31 The Australasian Menopause Society32 and the North American Menopause Society33 oppose the use of bio-identical HT, and the medical defence organisations are unlikely to cover the prescribing medical practitioner if there is an adverse patient outcome. However, if a patient has been using this treatment for more than a few months, it may be prudent to perform endometrial surveillance (e.g. transvaginal ultrasound and perhaps an endometrial biopsy31).

PREMATURE MENOPAUSE

Around 1–2% of women will be spontaneously menopausal before the age of 40 years.34 Some of the causes of premature ovarian failure (POF) are summarised in Box 53.3.

LONG-TERM ISSUES

Hormone therapy remains a valid treatment option for some women with osteopenia or osteoporosis, although evidence suggests that HT would need to be taken for over 10 years, by which time the risks may outweigh the benefits. The RCTs to date suggest that HT has no role in the prevention of heart disease or dementia.2,12,22

Australasian Menopause Society. http://www.menopause.org.au.

International Menopause Society. http://www.imsociety.org.

Jean Hailes Foundation for Women’s Health. http://www.jeanhailes.org.au.

North American Menopause Society. http://www.menopause.org.

Women’s Health and Research Institute of Australia. http://www.whria.com.au.

1 Sherman S. Defining the menopause transition. Am J Med. 2005;118(12B):35-75.

2 Blake J. Menopause: evidence-based practice. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20(6):799-839.

3 Dennerstein L, Dudley EC, Hopper JL, et al. A prospective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:351-358.

4 Peeyananjarassri K, Cheewadhanaraks S, Hubbard M, et al. Menopause symptoms in a hospital-based sample of women in southern Thailand. Climacteric. 2006;9:23-29.

5 Toulis KA, Tzellos T, Kouvelas D, et al. Gabapentin for the treatment of hot flashes in women with natural or tamoxifen-induced menopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Therapeutics. 2009;31(2):221-235.

6 Hafiz I, Lui J, Eden J. A quantitative analysis of the menopause experience of Indian women living in Sydney. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 2007;47:329-334.

7 Lu J, Lui J, Eden J. The experience of menopausal symptoms by Arabic women in Sydney. Climacteric. 2007;10:72-79.

8 Liu J, Eden J. Experience and attitudes toward menopause in Chinese women living in Sydney—a cross-sectional survey. Maturitas. 2007;58(4):359-365.

9 Liu J, Eden J. The menopausal experience of Greek women living in Sydney. J North Am Menopause Soc. 2008;15(3):476-481.

10 Hilditch JR, Lewis J, Peter A, et al. A menopause-specific quality of life questionnaire: development and psychometric properties. Maturitas. 1996;24:161-175.

11 Australian Menopause Society. Oestrogen deficiency symptom score, using MENQOL. Online. Available: http://www.menopause.org.au/education/Edu_html.asp?ID=89.

12 Viera A, Bond M, Yates S. Diagnosing night sweats. Am Family Physician. March 2003. Online. Available: http://www.aafp.org/afp/2003/0301/p1019.html.

13 Daley AJ, Stokes-Lampard HJ, Macarthur C. Exercise to reduce vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: a review. Maturitas. 2009;63(3):176-180.

14 Villaverde-Gutierrez, et al. Quality of life of rural menopausal women in response to a customized exercise programme. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(1):11-19.

15 Grady DG. Management of menopausal symptoms. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1176-1178.

16 Brzezinski A, Adlercreutz H, Shaoul R, et al. Short-term effects of phytoestrogen-rich diet on postmenopausal women. Menopause: J North Am Menopause Soc. 1997;4:89-94.

17 Eden JA. Herbal medicines for menopause: do they work and are they safe? Med J Aust. 2001;174(2):63-64.

18 Nelson HD, Vesco KK, Haney E, et al. Non-hormonal therapies for hot flushes. Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;295(17):2057-2071.

19 Osmers R, Friede M, Liske E, et al. Efficacy and safety of isopropanolic black cohosh extract for climacteric symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1074-1083.

20 Uebelhack R, Blohmer JU, Graubaum HJ, et al. Black cohosh and St John’s wort for climacteric complaints. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:247-255.

21 Palacio C, Masri G, Arshag D. Black cohosh for the management of menopausal symptoms. A systematic review of the clinical trials. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(1):23-36.

22 Nedrow A, Miller J, Walker M, et al. Complementary and alternative therapies for the management of menopause-related symptoms. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1453-1465.

23 MacLennan AH. HRT: a reappraisal of the risks and benefits. Med J Aust. 2007;186(12):643-646.

24 Katalinic A, Rawal R. Decline in breast cancer incidence after decrease in utilisation of hormone replacement therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(3):427-430.

25 Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. J Am Med Assoc. 2007;297(13):1465-1477.

26 The WHI steering committee. Effects of conjugated equine estrogen in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy. J Am Med Assoc. 2004;291:1701-1712.

27 Cummings SR, Ettinger B, Delmas PD, et al. The effects of tibolone in older postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:697-708.

28 Kenemans P, Bundred NJ, Foidart JM, et al. Safety and efficacy of tibolone in breast-cancer patients with vasomotor symptoms: a double-blind, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(2):135-146.

29 Panay N, Al-Azzawi F, Bouchard C, et al. Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric. 2010;13(2):121-131.

30 Cirigliano M. Bioidentical hormone therapy: a review of the evidence. J Women’s Health. 2007;16(5):600-631.

31 Eden JA, Hacker NF, Fortune M. Three cases of endometrial cancer associated with ‘bioidentical’ hormone replacement therapy. Med J Aust. 2007;187(4):244-245.

32 Australasian Menopause Society. Bioidentical hormones (troches) advice to consumers. 29 November 2003. Online. Available: http://www.menopause.org.au/content/view/211/102/.

33 North American Menopause Society. Bioidentical hormone therapy. Online. Available: http://www.menopause.org/bioidentical.aspx.

34 Meskhi A, Seif MW. Premature ovarian failure. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2006;18:418-426.