Chapter 25 Menopause

Introduction

The definition of menopause is when there is no menstruation over a 12-month period. That is, when menstrual periods permanantly stop. Women undergo significant reproductive transitional and physiological changes which are accompanied by the additional effects of ageing and social adjustment. This phase known as the climacteric or perimenopause describes the time leading up to a woman’s final menstruation, along with the endocrinological, biological, and clinical features of the approaching menopause. The length of this transition is usually about 4 years, but is shorter in smokers than non-smokers.1 Ten percent of women may not experience this phase and menses may stop abruptly. The median age for menopause is 51 years, over an age range of 39–59 years.1, 2

This transitional phase is associated with a number of vasomotor, urinary symptoms and psychological tribulations (Table 25.1). There is a variation in symptoms experienced.

Table 25.1 Physical, vasomotor and urogenital symptoms, and psychological problems encountered by women approaching and during menopause

| Physical/vasomotor symptoms | Urogenital symptoms | Psychological problems |

|---|---|---|

| Hot flushes |

The severity of symptoms that women may experience range from mild to severe. Approximately 40–65% of women experience hot flushes or night sweats, 30–60% disturbed sleep, and 25–35% vaginal dryness which leads women to consult health professionals.3 The duration of these symptoms may vary from 2–20 years.4

The most effective treatments for hot flushes include oestrogens and progestagens.2 Current evidence supports short-term use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) as the standard therapy for hot flushes.5, 6 Since the Women’s Health Initiative and Millenium study findings with long-term use of HRT in menopausal women, demonstrated increased risk of breast cancer7 more women are turning to non-pharmacological and various complementary medicines (CMs) for the relief of menopausal symptoms. Many women are reluctant to accept hormonal treatments, except when symptoms are severe, as they see this stage of their lives as a natural event, and not a disease. Menopause is an opportunity for lifestyle changes and it is worthwhile exploring prevention strategies, as women who commence HRT for hot flushes are likely to re-experience them after stopping HRT, even after 5 years.8

Lifestyle changes

Reduced physical activity, low socioeconomic status and cigarette smoking (past and current) are contributors documented to increase the relative risk of hot flushes in menopausal women.9 A recent review has reported that lifestyle and diet adjustment interventions have the potential to significantly improve menopausal symptoms.10, 11 Hence, lifestyle behaviours are important determinants of menopausal symptoms. The available literature suggests that smoking and greater body weight are risk factors for vasomotor symptoms; women with vasomotor symptoms who smoke may benefit from smoking cessation, and women who are heavier than ideal body weight may benefit from weight reduction.12

Body mass/overweight

Very obese women have significantly higher odds of experiencing hot flushes compared with normal weight women. Whilst the mechanism is not clear, oestrogen levels may partly explain this relationship.13

Cigarette smoking

A case-control study of 611 middle-aged women (45–54 years) demonstrated that past and current smokers have higher odds of experiencing hot flushes compared with never smokers.14 Past and current smoking and duration of smoking influenced frequency and the severity of hot flushes. The longer the women smoked, the more severe the symptoms. Smoking did not influence blood levels of estradiol and estrone and the risk persisted even when women were treated with hormones. Cigarette smoking is therefore a strong predictor of experiencing hot flushes, including the severity of hot flushes.

Cultural differences

There are many cultures where the prevalence of menopausal symptoms is reported as low. Prevalence rates for vasomotor symptoms in surveys of women (on average 2-week recall of symptoms) conducted between 2000–2005 include:15 of interest, the lowest reported symptoms are found in peasant Greek women and Mayan women from Mexico.15, 16

Under-reporting of symptoms by women in surveys may also contribute to low prevalences. It is not clear why the incidence of menopausal symptoms vary in different geographical areas. A recent review has reported that the prevalence variation of these symptoms may be influenced by a range of factors, including climate, diet, lifestyle, women’s roles, and attitudes regarding the end of reproductive life and ageing.17 Women’s attitude and expectations that can influence the experience of the perimenopause are determined by a number of factors including cultural attitudes and expectations, medicalisation (menopause viewed as an illness), their reproductive history, general health, mother’s experience, marital status, relationships with and attitude by their husbands/partners, extended family, social support, career and religious belief. In general, a healthy lifestyle, namely diet (e.g. foods high in phytoestrogens and isoflavones), exercise and avoiding smoking, and strong support from friends and family can positively impact on menopausal symptoms.15

Health practitioners and other caregivers should recognise that variations exist and ask patients specific questions about symptoms and their impact on usual functioning.17–20

Core body temperature

Possible mechanisms for hot flushes include the effects of oestrogen on norepinephrine/noradrenaline and serotonin receptors in the hypothalamus21 and genetics may also play a role.22 Research evidence suggests that small temperature elevations preceding hot flushes may constitute a triggering mechanism.20, 23 In addition, higher body core temperature prior to and during sleep is significantly associated with poorer quality of sleep and higher luteinizing hormone (LH) levels.24

Mind–body medicine

Psychological support

In a study of 78 menopausal women suffering hot flushes and breast cancer, the women were randomised to education and psychosocial support groups or a control group.25 A significant improvement in symptoms was found with the active treatment.25 A recent pilot trial demonstrated a possible effectiveness of cognitive behavioural interventions for the treatment of climacteric syndrome.26 A further pilot investigating cognitive behavioural group therapy (CBGT) supported the notion that CBGT interventions aimed at reducing vasomotor symptoms may be of value for menopausal hot flushes when administered in a small-group format.27 A recent systematic review has concluded that psycho-educational interventions seem to alleviate hot flushes in menopausal women and breast cancer survivors.28

Relaxation therapies

Nervous tension may cause instability of the thermoregulatory centre leading to sudden, transient, and erratic peripheral vasodilation in the skin blood vessels causing the sensation of flushing.29 Interestingly, even excitement, such as laughter, can stimulate the nervous system and bring on more hot flushes. Relaxation can alleviate menopausal symptoms.28

Three randomised control trials (RCTs) identified by the North American Menopausal Society,30 demonstrated paced respiration (slow, controlled, diaphragmatic breathing) reduced hot flushes by 50%, particularly if performed at the onset of a hot flush when compared with controls. A pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for hot flushes has shown a positive result in improving both quality of life and reducing severity of hot flushes in 15 women experiencing severe hot flushes over the course of treatment.31

Physical activity/exercise

Aerobic exercise and customised exercise programs

Physical activity may ameliorate hot flushes and insomnia by influencing opioid levels.32 It is known that opioid levels are lowered in menopause and that exercise can increase opioid levels such as endorphins and activity.33 Although data supporting physical activity are still preliminary recent studies suggest that women who exercise regularly are less likely to experience severe hot flushes.34 A customised exercise program is valuable for improving the health related quality of life of menopausal women compared to those who do not perform any form of physical activity.35

A Cochrane review of RCTs identified 1 small trial that compared exercise with HRT and found both interventions were effective in reducing vasomotor symptoms, although HRT was more effective than exercise.36

A recent systematic review of the literature of RCTs found aerobic exercise improves psychological health and quality of life in vasomotor symptomatic women.37 The review also identified several RCTs of middle-aged menopausal women and found aerobic exercise can invoke significant improvements in this age group of menopause-related symptoms such as mood, health-related quality of life and insomnia compared with middle-aged women who did not exercise.37

Yoga

Yoga can play an important role in the management of menopausal symptoms. A number of trials support the recommendation of specific yoga exercises as an evidence-based prescription for menopausal symptoms.38, 39, 40

A recent randomised control study of 180 perimenopausal women comparing yoga comprised of breathing practises, sun salutation and meditation was found to be significantly beneficial for reducing hot flushes and night sweats and improving cognitive functions such as memory, mental balance, attention, concentration and recall when compared with control group; a set of simple physical exercises, under supervision.41

A trial of 120 women (aged 40–55 years) with menopausal symptoms randomised women into 2 study arms: yoga and an exercise (control) group.42 In the yoga therapy group, women were instructed to practise various yoga postures such as sun salutation that consists of 12 postures, pranayama (breathing practices) and avartan dhyan (cyclic meditation). Women in the control group were instructed a set of simple physical exercises (supervision by trained teachers). Women in both groups practised either yoga or physical exercises 1 hour daily, 5 days per week over the 8-week study period.

The perimenopausal women in the yoga therapy group demonstrated significantly reduced perceived stress, climacteric symptoms, and neuroticism traits compared with controls.42

A systematic review that explored the role of meditation and yoga for treating diseases concluded the strongest evidence for efficacy was found for epilepsy, symptoms of the premenstrual syndrome and menopausal symptoms.43

However, a recent systematic review of 7 studies reported mixed results and the evidence at present is insufficient to suggest that yoga is effective in menopause.44

Some studies did not demonstrate any benefit of yoga on menopausal symptoms, sleep or self-esteem in menopausal women.44, 45, 46

Nutritional influences

Calcium and vitamin D for menopausal women

There is a role for the recommendation of calcium and vitamin D (cholecalciferol) supplementation by menopausal women with demonstrated vitamin D deficiency for the prevention of osteoporosis. Routine use, however, is questionable. (See Chapter 30 for osteoporosis.)

A Cochrane review of 45 trials, found vitamin D alone is not effective in preventing hip fracture, vertebral fracture or any new fracture.47 Vitamin D with calcium reduced hip fractures especially in people in institutional care, but not significantly in the community-dwelling subgroup.47

The World Health Initiative for the calcium/vitamin D RCT of 36 282 post-menopausal women (aged 51–82 years) from 40 US clinical centres assigned to 1000mg of elemental calcium carbonate and 400IU of vitamin D(3) daily or placebo with average follow-up of 7 years, found that supplementation did not have a statistically significant effect on mortality rates but may reduce mortality rates in post-menopausal women.48

Furthermore, findings from the Women’s Health Initiative study also found adherence to calcium and vitamin D supplements over 4 years did not produce any favourable effects compared to placebo on physical functioning or physical performance in the older women.49

Phytoestrogens and isoflavones in diet

Phytoestrogens are oestrogenic compounds found in plants and consist of isoflavones, lignans and coumestans (Table 25.2).50 Isoflavones have a similar structure to oestrogen and have the capacity to exert both mild oestrogenic effects in menopausal women and anti-oestrogenic effects in pre-menopausal women.50 Comparative surveys of Japanese women and parallel groups of women from Canada and North America determined significant differences in the incidence of hot flushes and nocturnal sweating during premenopausal, perimenopausal and post-menopausal phases.51

| Phytoestrogen food sources | Phytoestrogen content (μg/100g) |

|---|---|

| Flax seed | 379380 |

| Soy beans | 103920 |

| Tofu | 27150.1 |

| Soy yoghurt | 10275 |

| Sesame seed | 8008.1 |

| Flax bread | 7540 |

| Black bean sauce | 5330.3 |

| Multigrain bread | 4798.7 |

| Soy milk | 2957.2 |

| Hummus | 993 |

| Soy bean sprouts | 789.6 |

| Garlic | 603.6 |

| Mung bean sprouts | 495.1 |

| Dried apricots | 444.5 |

| Alfalfa sprouts | 441.4 |

| Pistachio nuts | 382.5 |

| Dried dates | 329.5 |

| Sunflower seed | 216 |

| Chestnuts | 210.2 |

| Dried prunes | 183.5 |

| Olive oil | 180.7 |

| Walnuts | 139.5 |

| Almonds | 131.1 |

| Green beans | 105.8 |

| Broccoli | 94.1 |

| Cabbage | 80 |

| Peaches | 64.5 |

| Strawberry | 51.6 |

| Peanuts | 34.5 |

| Onion | 32 |

| Blueberry | 17.5 |

| Corn | 9 |

| Coffee with cow’s milk | 6.3 |

| Watermelon | 2.9 |

| Milk, cow | 1.2 |

(Source: adapted and modified from Thompson LU, Boucher BA, Lui Z, et al. Phytoestrogen content of foods consumed in Canada, including isoflavones, lignans and coumestan. Nutrition and Cancer 2006; 54:184–201.)

However, a diet high in phytoestrogens alone is probably less successful in addressing menopausal symptoms without a change in lifestyle and more physical activity as well as the awareness of a low-calorie diet and stress management. This notion was evident in a cross-cultural comparison of health-related quality of life in Australian and Japanese midlife women.52 It was reported that if the women had a lowered body mass index, undertook physical activity, consumed dietary phytoestrogens, and consumed some alcohol (any regular use of alcohol) their physical functioning seemed to be better.52

Asians and Japanese ingest on average 25–45mgs isoflavones per day over long periods of time. Just 40mg of isoflavones alone is sufficient to reduce menopausal symptoms which are up to 50 000 times higher than levels of endogenous estradiol.15

Furthermore, a high-phytoestrogen diet especially if initiated before puberty is associated with reduced risk of breast, colon and prostate cancer.53, 54

Middle-aged Japanese women are generally healthier than North American women, have lower rates of heart disease, breast cancer and osteoporosis, and have one of the longest life expectancy in the world (mean 85.33 yrs).51

The incidence of breast cancer is one-third compared with North American women, for osteoporosis less than half of Caucasian women in North America, even though Asian women have lower bone density, and 28% suffer a chronic health problem such as diabetes, allergies, asthma, arthritis and hypertension compared with 45% of Canadian (Manitoban) women and 53% of US (Massachusetts) women.15

The authors attribute these results to exercise, including weight-bearing exercise, no smoking, minimal consumption of alcohol and coffee, and a low-fat diet high in soybeans, vegetables and herbal teas (phytoestrogen-rich).15

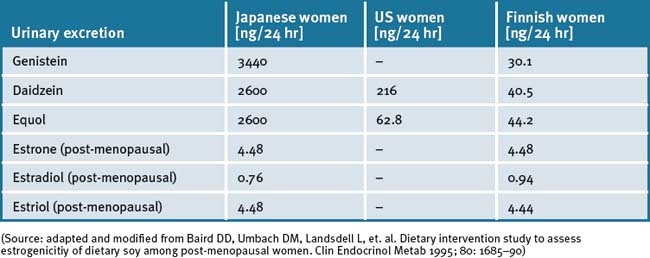

Comparative studies of Japanese-oriental women, US and Finnish women proved that the Japanese women had a 60 to 110 times higher amount of isoflavones excreted in the urine while the concentration of oestrone and oestradiol was nearly identical and the amount of oestradiol was slightly less.55 The average age in both groups (Japan and Finland) was 50.4 years. Both groups came from rural regions, therefore the socio–psychological differences were less than assumed. The measured higher concentrations of isoflavones in Japanese women were attributed to high consumption of soy products such as tofu, miso, aburage, atuage, koridofu as well as cooked soy beans. It was concluded that this dietary factor was responsible for less climacteric complaints and protective effect against cancer. (See Table 25.3.)

Nutritional supplements

Phytoestrogens

Safety concerns with the use of phytoestrogen supplements have been raised,56 but the general consensus is that they are safe except where there is still uncertainty in some situations such as in women with breast cancer.57 Phytoestrogens can also competitively bind to oestrogen receptors, displacing more potent oestrogens, and potentially decrease the overall oestrogenic effect in the premenopausal woman.58

Recent evidence demonstrates that a high dietary soy intake in women with a history of oestrogen and progesterone positive receptor breast cancer, had a significantly lower risk of breast cancer recurrence while taking tamoxifen.59

Soy (Glycine max L.) isoflavone extracts

A randomised double-blind, placebo-controlled trial has demonstrated that supplementation of soy isoflavones up to 100mgs/day for 4 months in post-menopausal women reduced cholesterol and menopausal symptoms by 21%.60

In another RCT, 25g of soy protein alone was able to reduce total cholesterol and LDL-cholesterol (-29.0 and -24.0mg/dL, p<0.001 and p<0.006) after 16 weeks compared with placebo and resistance exercise.61

Other studies have demonstrated its effectiveness only when the diet involved increasing phytoestrogen intake. Murkies et al.62 demonstrated that after 3 months, the soy flour supplementation evidenced a 40% reduction in hot flushes compared with controls fed wheat flour resulting in only 25% reduction. Advising patients to add 2 tablespoons of soy grits to their diet, such as cereal, may be comparable.

A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled study of 80 post-menopausal women (mean age = 55.1 years), who reported 5 or more hot flush episodes per day, were randomised to receive either 250mg of standardised soy extract (Glycine max AT) a total of 100mg/day of isoflavone or placebo.63

A 12-week randomised placebo-controlled trial of 84 post-menopausal women randomised to 20g of soy protein containing 160mg of total isoflavones or taste-matched placebo (20g whole milk protein) demonstrated a significant improvement in all 4 quality-of-life subscales (vasomotor, psychosexual, physical, and sexual) among the women taking isoflavones compared with no changes observed in the placebo group.64

Another study has also demonstrated efficacy and safety of a soy isoflavone extract in post-menopausal women.65 The soy isoflavone extract exerted favourable effects on vasomotor symptoms and compliance was good, providing a safe and effective alternative therapy for post-menopausal women.

However, RCTs have yielded mixed results for the effectiveness of soy isoflavones for menopausal symptoms due to various factors such as small sample sizes, short-term treatment and variation in dosage used. In addition, there is sub-population and individual variation in the metabolisation of daidzein which converts to the more bioactive estrogenic product equol by the gut bacteria. Western women are only 30% equol producers compared with 50–60% of Japanese women.15

A recent Cochrane review66 concluded that there was no evidence of effectiveness in the alleviation of menopausal symptoms with the use of phytoestrogen treatments.

Yet another systematic review and meta-analysis of multiple RCTs using a non-random effects model, demonstrated that isoflavone therapy had a significant 30% reduction in frequency hot flushes, especially in women with frequent hot flushes.67

Interestingly it has also been reported that the quality of soy phytoestrogens is almost certainly likely to influence efficacy.68

Herbal medicine

Herbal medicines may play a role in short-term management of the symptoms of menopause.

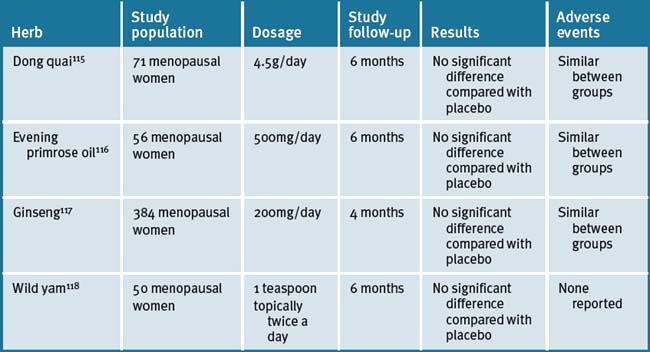

A review of the literature found the majority of studies indicate that extract of black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) improves menopause-related symptoms, although the quality of studies is poor.69 Studies for isoflavone red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) leaf extracts to relieve menopausal symptoms are contradictory. When compared with placebo, the largest study showed no benefit for reducing menopausal symptoms for 2 different red clover isoflavone products.69 Clinical trials for the use of dong quai (Angelica sinensis L.), ginseng (Panax ginseng), or evening primrose seed oil (Oenothera biennis L.) demonstrate these are ineffective for improving menopausal symptoms.69

Another review suggests that isoflavones found in soy foods and red clover appear to have a ‘small but positive health effect on plasma lipid concentrations, bone mass density, and cognitive abilities’.70

Red clover (Trifolium pratense)

Red clover is a member of the legume family and contains high levels of isoflavones, namely genistein, and significantly less daidzein compared with soy. Daidzein converts to the more bioactive equol, which exerts stronger estrogenic effects, and may explain why red clover is less effective than soy extracts in clinical trials.71, 72

The majority of placebo–controlled, randomised, double-blind studies have resulted in no effect of 40–160mg isoflavones (red clover isoflavones).73, 74

Three blinded randomised trials with red clover supplements containing either 57mgs/day isoflavones or 40mgs/day isoflavones found no benefit for hot flushes in peri- and post-menopausal women.75 A further trial of 30 women aged 49–65 years, after 4 weeks, reported reduced hot flushes with 80mgs/day of red clover propriety extract compared with placebo.76 Another similar trial demonstrated red clover to reduce symptoms of menopause with up to 73% of women experiencing a significant improvement, 50% reduction of hot flushes and 47% reduction in night sweats within 6 weeks of treatment.76 However, a systematic review identified 5 trials measuring the effects of T. pratense isoflavones on vasomotor symptoms in menopausal women.77 The meta-analysis only indicates a small reduction in hot flush frequency in women receiving active treatment (40–80mg/day) compared with those receiving placebo. A recent, large US clinical trial concluded that the red clover extract had no clinically important effect on hot flashes or other symptoms of menopause.78

A more recent systematic review and meta-analysis confirms efficacy of red clover extract.79 It was concluded that there was evidence (albeit small) from T. pratense isoflavones for treating hot flushes in menopausal women. Minimal side-effects and no serious safety concerns were associated with short-term use of red clover, although technically one would avoid its use in estrogenic related health problems such as breast and endometrial cancers due to its high oestrogenic content, although this is not well established. A double-blinded placebo-controlled trial of 30 perimenopausal women demonstrated no proliferative effects on the endometrium by biopsy after 12 weeks of use with red clover-derived isoflavone extract, suggesting it may possibly have an anti-oestrogenic effect on the uterus.80 A recent review of the literature confirms this finding.81 Red clover demonstrates some efficacy in maintenance of bone health and improvement of arterial compliance.82

Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa)

Black cohosh has been traditionally used in North American Indian medicine to treat gynaecological disorders including menopause. The German Commission E lists black cohosh for the treatment of menopausal symptoms, as well as PMS and dysmenorrhoea, and is only recommended for use up to 6 months because of the lack of long-term safety data.83

There have been numerous trials investigating the effectiveness of black cohosh to abrogate menopausal symptoms.84, 85 A recent review has reported that black cohosh and foods that contain phytoestrogens show promise for the treatment of menopausal symptoms.84

Several small studies of a propriety extract of isopropanolic extract of black cohosh have revealed a trend to reducing vasomotor symptoms, however only 1 large trial with 304 post–menopausal women (mean age 54 years) has demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in hot flushes.86 This study compared isopropanolic extract of black cohosh at 40mg twice daily versus placebo for 12 weeks. The treatment group showed significant improvement with hot flushes, urinary symptoms, vaginal dryness and mood. Liver function tests did not alter in both groups. A recent review came to similar conclusions.83 The authors concluded that the isopropanolic extract of black cohosh root stock is effective in relieving climacteric symptoms, especially in early climacteric women.

None of the studies in the review investigated adverse events with black cohosh but other studies have reported that it is generally well tolerated and the commonest adverse reaction reported is gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, dyspepsia and abdominal upset).87, 88

A multi-centre, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel group study conducted on 122 menopausal women treated over 12 weeks found Cimicifuga racemosa dried ethanolic extract significantly reduced hot flushes in women with severe symptoms by 47% compared with 21% in the placebo group.89

Another trial found isopropanolic Cimicifuga racemosa (iCR) therapy just as effective as tibolone for alleviation of moderate to severe climacteric symptoms.90

In an RCT 64 post-menopausal women (45–55 years old) with severe hot flushes, at least 5 daily, were randomised in a 3-month trial to 40mg isopropanolic aqueous iCR extract daily or 25mcg low-dose transdermal estradiol (TTSE2) plus dihydrogesterone 10mg/day for the last 12 days of the 3-month estradiol treatment.91

At the end of 3 months, both groups significantly reduced hot flushes with no difference between them. Also symptoms of anxiety and depression reduced but no change in urogenital symptoms in either group. The overall trend for improvement was in the TTSE2 group. Other findings included reduction in total cholesterol in the TTSE2 group, significant reduction in low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-cholesterol) in both groups and black cohosh group significantly increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-cholesterol). There was no change in liver function tests, serum triglyceride levels or endometrial thickness in either group. A rise in prolactin and oestradiol was noted in the TTSE2 group but not the black cohosh group. No significant adverse effects were observed in either group.91

When compared with fluoxetine, black cohosh was more effective for treating hot flushes and night sweats in post-menopausal women.92

In the prospective randomised trial, when compared with fluoxetine treatment, supplementation with black cohosh was more effective for treating hot flushes and night sweats in post-menopausal women.

At the end of the 6-month trial, black cohosh reduced the hot flush score by 85%, compared with a 62% in the fluoxetine.92

There are also a number of trials that demonstrated black cohosh was not effective for the alleviation of menopausal and vasomotor symptoms.93, 94

One trial demonstrated black cohosh (1 capsule, Cimicifuga racemosa 20mg BID) was less efficacious than placebo in alleviating symptoms of menopause in women with breast cancer.95

Black cohosh and breast cancer

The relationship of phytoestrogen herbs and breast cancer is not well established. There have been conflicting reports about black cohosh having estrogenic properties.96

It appears that black cohosh does not exert oestrogenic properties. The main active ingredients of black cohosh are triterpenes. The activity and mechanism of action of these compounds are largely unknown. One study aimed to compare the effects of 2 black cohosh preparations, analysed for triterpene content and compared this to their efficacy for menopausal symptoms.97

A population-based retrospective case-control study in 3 US counties (Philadelphia area), looked at 949 menopausal women with breast cancer cases and 1524 controls. It concluded the use of black cohosh had a ‘significant breast cancer protective effect (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 0.39, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.22–0.70)’.98

An epidemiologic observational retrospective cohort study over an average of 3.6 years of 18 861 breast cancer women, including oestrogenic dependent cancers, 1102 of these women were on iCR therapy. The study endpoint was disease-free survival following a diagnosis of breast cancer. After controlling for confounders such as tamoxifen and age, the study found ‘a protractive effect of iCR on the rate of recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] 0.83, 95% CI 0.69–0.99)’.99

Following initial diagnosis, 14% of the control group had developed a recurrence after 2 years and the iCR group reached this proportion after 6.5 years. The authors concluded iCR is ‘not associated with increased risk of recurrence of breast cancer but associated with prolonged disease-free survival’.99 This implies that black cohosh may have a protective effect toward recurrence of breast cancer.

Adverse reactions to black cohosh

Hepato-toxicity has been reported worldwide in a number of patients who presented with serious liver problems such as hepatitis associated with the use of several herbal products containing black cohosh.100, 101 There have also been rare reports of liver failure requiring liver transplantation, raising concern with the daily therapeutic use of the herb.102, 103 Hepatic reactions are likely to be idiosyncratic and occur rarely compared with the overall rate of use of black cohosh internationally.

A systematic review of clinical trials suggested black cohosh to be overall relatively safe. The review included 3 post-marketing surveillance studies, 4 case series, 8 single case reports and clinical studies.104

Systematic reviews for black cohosh

An early review of the literature of 4 RCTs as well as many more less rigorous studies found 3 of the 4 RCTs, conducted on menopausal women taking black cohosh in Germany, were useful for the control of not only hot flushes but also mood.104 These trials demonstrated a significant effect on menopausal symptoms over placebo with no oestrogenic effect on vaginal epithelium.

Another review of the literature of black cohosh effects on vasomotor symptoms identified 32 papers.106

Another systematic review found the evidence from 6 studies with a total of 1112 perimenopausal and post-menopausal women did not consistently demonstrate an effect of black cohosh on menopausal symptoms and suggested further rigorous trials were warranted.107

Further research is warranted to help identify the useful extract, dosage and exactly who is at risk of adverse reactions with black cohosh therapy.

St John’s wort (SJW) (Hypericum perforatum)

A double, blind RCT over 16 weeks of 301 women with climacteric and psychological symptoms who were randomised to ethanolic St John’s wort extract and isopropanolic black cohosh extract, or a matched placebo. The study assessed both climacteric symptoms (Menopause Rating Scale mean score) and psychological complaints (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale sum score).108 The study reported reduced symptoms of 50% in the treatment group versus 19.6% in the placebo arm. Also reduced symptoms of depression in the treatment group of 41.8% compared with the placebo group of 12.7%. The study concluded that the treatment group was significantly (P<0.001) superior to placebo in both measures of menopause and depression, there were no differences regarding adverse events, laboratory values, or tolerability. The fixed combination of black cohosh and St John’s wort was superior to placebo in alleviating climacteric complaints, including the related psychological component.

A prospective, controlled open-label observational study of 6141 women at 1287 outpatient gynaecologists in Germany followed up over 6 months and optionally at 12 months found the combination therapy of black cohosh and St John’s wort more superior for the alleviation of both psychological and menopausal symptoms compared with the use of St John’s wort alone. St John’s wort also alleviated psyche symptoms, but not to the same degree as the combined formula. Adverse events were rare and non-serious: rate of 0.16%.109

Another trial of combined black cohosh and St John’s wort also demonstrated efficacy for climacteric symptoms.110

In a further and recent clinical trial with St John’s wort combined with Vitex agnus-castus (chaste tree berry) in the management of menopausal symptoms, it was reported that the herbal combination was no more effective than placebo.111

Hop extract (Humulus lupulus L.)

A recent double-blind randomised study investigated the efficacy of a hop extract (Humulus lupulus L.) to alleviate menopausal discomforts. The study concluded that the daily consumption of a hop extract, standardised on 8-prenylnaringenin (8-PN, the phytoestrogen in hops, Humulus lupulus L.) which is a potent phytoestrogen, exerted favourable effects on vasomotor symptoms and other menopausal discomforts.112

Mixed herbal formula

A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 50 post-menopausal women were randomised to a herbal mixture containing black cohosh, dong quai, milk thistle, red clover, American ginseng and chaste tree berry or placebo. After 3 months of treatment, the herbal group demonstrated reduced hot flushes (>73%), reduction in night sweats (69%), reduction in intensity of hot flushes and improved sleep quality. The hot flushes ceased completely in 47% of women compared with only 19% in placebo group. There were no changes observed on vaginal ultrasound, hormone levels (estradiol, FSH), liver enzymes or thyroid in either group.113

Other herbal supplements

A Mayo Clinic trial found that flaxseed reduced hot flushes.114 Other herbs implicated in having benefit for menopausal symptoms, with little or no research, include dong quai, evening primrose oil, Panax ginseng, gingko, wild yam, fennel, red sage, liquorice root and sarsaparilla root.115–118

Gingko biloba

Gingko biloba extract contains 24% of phytoestrogens (kaempferol, quercetin and isorhamnetin) which demonstrate weak estrogenic activities through the oestrogen response pathway by an interaction with oestrogen receptors.119

Ginseng (Panax ginseng)

An extract of ginseng, ginsenoside-Rb1, a weak phytoestrogen, is also known to exhibit oestrogenic activity by binding and activating oestrogen receptors.120, 121, 122

Wild yam (Dioscorea villosa)

Wild yam is a species of plant with edible roots (called yams) and is grown in abundance in humid (tropical) conditions. Some varieties of yams are consumed as foods. Wild yam was traditionally used by the Maya and Aztec civilization for colic, rheumatism and relief of inflammation and pain (e.g. cramps and arthritis). Wild yam is rich in steroidal saponin (sapogenin). Since the 1940s, the Japanese successfully isolated diosgenin from dioscin in wild yam, used to synthesise progesterone, making it attractive for its use in menopause, although there is no research to support the use of wild yam.118

For a list of herbs used in the treatment of hot flushes, but with limited supporting evidence,123 see Table 25.4.

Vitamins

Vitamin E

Vitamin E is reported to be regularly used by post-menopausal women.82 However, the data from clinical trials is controversial. In 1 small placebo control trial 125 women with a history of breast cancer were given 800IU/day vitamin E supplementation for 9 weeks. The study demonstrated that on cross-over there was a slight improvement in menopausal symptoms (reduction in hot flash frequency) compared with placebo with a similar incidence of adverse events reported in both groups.124 A recent trial, however, has demonstrated that vitamin E at 400IU/day was effective for the treatment of hot flashes.125

Other non-hormonal treatments

A useful literature review identified non-hormonal treatments for menopause. Non-hormonal pharmaceuticals for menopausal symptoms include such compounds as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (e.g. paroxetine and sertraline, venlafaxine, gabapentin) mirtazapine and trazodone.126 (See Table 25.5.)

Table 25.5 Non–prescribed and prescribed non-hormonal compounds for the treatment of hot flushes

| Non-prescribed compounds | Prescribed compounds (non-hormonal) |

|---|---|

| Herbal medicines/plants/foods supplements |

(Source: adapted and modified from Carroll DG. Non-hormonal therapies for hot flashes in menopause. Am Fam Physician 2006;73(3):457–64)

Physical therapies

Acupuncture

The World Health Organization supports the use of acupuncture for the management of menopause. Recently a number of clinical trials have reported on the use of acupuncture in women with and without breast cancer for the relief of menopausal symptoms.127–131 In one study there were no significant effects for changes in hot flush interference, sleep, mood, health-related quality of life, or psychological wellbeing.127 The results suggested that either there was a strong placebo effect or that both traditional and sham acupuncture significantly reduce hot flash frequency.127 The second study was a long-term follow-up of acupuncture and hormone therapy on hot flushes in women with breast cancer.128 This study demonstrated a significant reduction in hot flushes and concluded that electro-acupuncture may be a possible treatment of vasomotor symptoms for women with breast cancer for this group of women.128 Three further studies on the use of acupuncture for menopausal symptoms in women with breast cancer have reported efficacy.129, 130, 131

However, the overall studies are methodologically poor and a number of systematic reviews have demonstrated mixed findings and failed to demonstrate acupuncture to be beneficial over sham acupuncture for climacteric symptoms.132, 133, 134

Conclusion

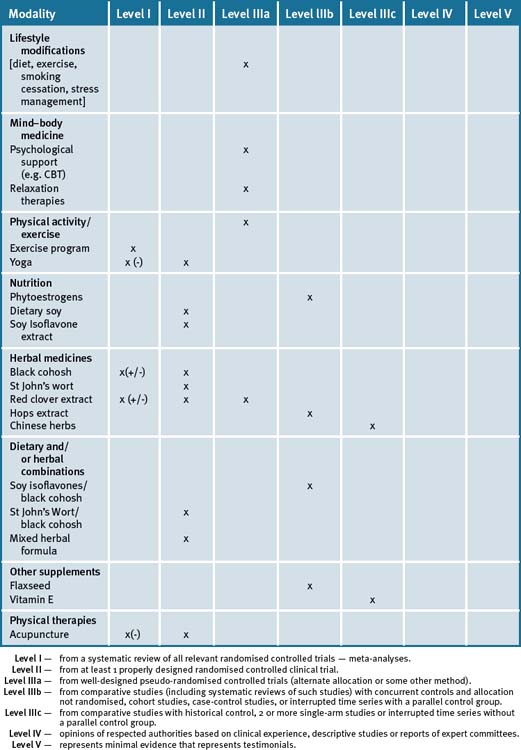

Women are seeking alternative options for the alleviation of symptoms associated with menopause. They view this time as a natural event and are concerned by side-effects associated with HRT. Although there have been a number of observational and epidemiologic studies conducted for the relief of menopausal symptoms, there is a continued need for further research on the efficacy as well as the long-term safety of herbal medicines and dietary supplements. An emergent body of scientific literature suggests that incorporation of some form of complementary therapy that promotes lifestyle changes, including suitable dietary changes, exercise and relaxation strategies, with the use of supplements/herbal medicines may result in significant improvement in clinical outcomes.135 Table 25.6 summarises the level of scientific evidence for lifestyle and non-drug approaches to managing menopause.

Clinical tips handout for patients — menopause

1 Lifestyle advice

2 Physical activity/exercise

3 Mind–body medicine (most helpful)

4 Environment

5 Dietary changes

7 Supplements

Phytoestrogens

Soy

Herbs

Black cohosh

Red clover

Traditional herbal medicine

1 Sowers M.R., Zheng H., McConnell D., et al. Follicle stimulating hormone and its rate of change in defining menopause transition stages. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008 Jul 22.

2 Nelson H.D. Menopause. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):760-770.

3 Shrader S.P., Ragucci K.R. Life after the women’s health initiative: evaluation of post-menopausal symptoms and use of alternative therapies after discontinuation of hormone therapy. Pharmacotherapy. 2006;26(10):1403-1409.

4 Ettinger B.N.I.H. State of the Science conference on management of menopause– related symptoms. Symptom relief versus unwanted effects: role of estrogen–progestin dosage and regime. Bathesda, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2005.

5 Stephenson J. FDA orders estrogen safety warnings: agency offers guidance for HRT use. JAMA. 2003;289:537-538.

6 [No authors listed] Estrogen and progestogen use in post-menopausal women: July 2008. Menopause: position statement of The North American Menopause Society; 2008 Jun 20.

7 Van Horn L., Manson J.E. The Women’s Health Initiative: implications for clinicians. Cleve Clin J Med. 2008;75(5):385-390.

8 Ockene J.K., Barad D.H., Cochrane B.B., et al. Symptom experience after discontinuing use of estrogen plus progestin. JAMA. 2005;294(2):183-193.

9 Position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Treatment of menopause associated vasomotor symptoms. Menopause. 2004;11:11-33.

10 Blake J. Menopause: evidence-based practice. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;20(6):799-839.

11 McKee J., Warber S.L. Integrative therapies for menopause. South Med J. 2005;98(3):319-326.

12 Greendale G.A., Gold E.B. Lifestyle factors: are they related to vasomotor symptoms and do they modify the effectiveness or side effects of hormone therapy? Am J Med. 2005;118(Suppl 12B):148-154.

13 Gallicchio L., Visvanathan K., Miller S.R., et al. Body mass, estrogen levels, and hot flashes in midlife women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005 Oct;193(4):1353-1360.

14 Gallicchio L., Miller S.R., Visvanathan K., et al. Cigarette smoking, estrogen levels, and hot flashes in midlife women. Maturitas. 2006 Jan 20;53(2):133-143.

15 Melby M.K., Lock M., Kaufert P. Culture and symptom reporting at menopause. Human Reproduction Update. 2005;11(5):495-512.

16 Martin M.C., Block J.E., Sanchez S.D., et al. Menopause without symptoms: the endocrinology of menopause among rural Mayan Indians. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168(6 Pt 1):1839-1843.

17 Freeman E.W., Sherif K. Prevalence of hot flushes and night sweats around the world: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2007;10(3):197-214.

18 Crawford S.L. The roles of biologic and nonbiologic factors in cultural differences in vasomotor symptoms measured by surveys. Menopause. 2007;14(4):725-733.

19 Schnatz P.F., Serra J., O’Sullivan D.M., et al. Menopausal symptoms in Hispanic women and the role of socioeconomic factors. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2006;61(3):187-193.

20 Freedman R.R. Physiology of hot flashes. Am J Hum Biol. 2001;13(4):453-464.

21 Freedman R.R. Core body temperature variation in symptomatic and asymptomatic post-menopausal women: brief report. Menopause. 2002 Nov-Dec;9(6):399-401.

22 Crandall C.J., Crawford S.L., Gold E.B. Vasomotor symptom prevalence is associated with polymorphisms in sex steroid-metabolizing enzymes and receptors. Am J Med. 2006;119:S52-S60.

23 Deecher D.C., Dorries K. Understanding the pathophysiology of vasomotor symptoms (hot flushes and night sweats) that occur in perimenopause, menopause, and post-menopause life stages. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(6):247-572.

24 Murphy P.J., Campbell S.S. Sex hormones, sleep, and core body temperature in older post-menopausal women. Sleep. 2007 Dec 1;30(12):1788-1794.

25 Ganz P.A., Greendale G.A., Petersen L., et al. Managing menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors: results of a randomised controlled trial. JNCI. 2000;92(13):1054-1064.

26 Alder J., Eymann Besken K., Armbruster U., et al. Cognitive-behavioural group intervention for climacteric syndrome. Psychoth Psychosom. 2006;75(5):298-303.

27 Keefer L., Blanchard E.B. A behavioural group treatment program for menopausal hot flashes: results of a pilot study. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2005;30(1):21-30.

28 Tremblay A., Sheeran L., Aranda S.K. Psychoeducational interventions to alleviate hot flashes: a systematic review. Menopause. 2008;15(1):193-202.

29 Stearns V., Ullmer L., López J.F., et al. Hot flushes. Lancet. 2002;360(9348):1851-1861.

30 North American Menopause Society. Treatment of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2004;11(1):11-33.

31 Carmody J., Crawford S., Churchill L. A pilot study of mindfulness-based stress reduction for hot flashes. Menopause. 2006;13(5):760-769.

32 Nelson D.B., Sammel M.D., Freeman E.W., et al. Effect of physical activity on menopausal symptoms among urban women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(1):50-58.

33 Gannon L., Stevens J. Portraits of menopause in the mass media. Women Health. 1998;27(3):1-15.

34 Stadberg E., Mattsson L.A., Milsom I. Factors associated with climacteric symptoms and the use of hormone replacement therapy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79(4):286-292.

35 Villaverde-Gutiérrez C., Araújo E., Cruz F., et al. Quality of life of rural menopausal women in response to a customized exercise programme. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(1):11-19.

36 Daley A., Stokes-Lampard H., Mutrie N., MacArthur C. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. (4):2007.

37 Daley A.J., Stokes-Lampard H.J., Macarthur C. Exercise to reduce vasomotor and other menopausal symptoms: a review. Maturitas. 2009 Jul 20;63(3):176-180.

38 Cohen B.E. Yoga: an evidence-based prescription for menopausal symptoms? Menopause. 2008 Sep-Oct;15(5):827-829.

39 Cohen B.E., Kanaya A.M., Macer J.L., et al. Feasibility and acceptability of restorative yoga for treatment of hot flushes: a pilot trial. Maturitas. 2007 Feb 20;56(2):198-204.

40 Booth-LaForce C., Thurston R.C., Taylor M.R. A pilot study of a Hatha yoga treatment for menopausal symptoms. Maturitas. 2007 Jul 20;57(3):286-295. Epub 2007 Mar 2

41 Chattha R., Nagarathna R., Padmalatha V., et al. Effect of yoga on cognitive functions in climacteric syndrome: a randomised control study. BJOG. 2008;115(8):991-1000.

42 Chattha R., Raghuram N., Venkatram P., et al. Treating the climacteric symptoms in Indian women with an integrated approach to yoga therapy: a randomised control study. Menopause. 2008 Sep-Oct;15(5):862-870.

43 Arias A.J., Steinberg K., Banga A., et al. Systematic review of the efficacy of meditation techniques as treatments for medical illness. J Altern Complement Med. 2006 Oct;12(8):817-832.

44 Lee M.S., Kim J.I., Ha J.Y., et al. Yoga for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. Menopause. 2009 May-Jun;16(3):602-608.

45 Elavsky S., McAuley E. Lack of perceived sleep improvement after 4-month structured exercise programs. Menopause. 2007 May-Jun;14(3 Pt 1):535-540.

46 Elavsky S., McAuley E. Exercise and self-esteem in menopausal women: a RCT involving walking and yoga. Am J Health Promot. 2007 Nov-Dec;22(2):83-92.

47 Avenell A., Gillespie W.J., Gillespie L.D., et al. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures associated with involutional and post-menopausal osteoporosis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2008. Issue 1. Art. No.: CD000227. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000227.pub3

48 LaCroix A.Z., Kotchen J., Anderson G., et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and mortality in post-menopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative calcium-vitamin D randomised controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009 May;64(5):559-567. Epub 2009 Feb 16

49 Brunner R.L., Cochrane B., Jackson R.D., et al. Calcium, vitamin D supplementation, and physical function in the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Diet Assoc. 2008 Sep;108(9):1472-1479.

50 Thompson L.U., Boucher B.A., Lui Z., et al. Phytoestrogen content of foods consumed in Canada, including isoflavones, lignans and coumestan. Nutrition and Cancer. 2006;54:184-201.

51 Lock M. Menopause in cultural context. Exp Gerontol. 1994 May-Aug;29(3-4):307-317.

52 Anderson D.J., Yoshizawa T. Cross-cultural comparisons of health-related quality of life in Australian and Japanese midlife women: the Australian and Japanese Midlife Women’s Health Study. Menopause. 2007;14(4):697-707.

53 Adlercreutz H. Phyto-oestrogens and cancer. The Lancet Oncology. 2002;3:364-373.

54 Ingram D., Saunders K., Kolybaba M., et al. Case-control study of Phyto-oestrogens and Breast Cancer and Plant Oestrogen. Lancet. 1997;350:990-994.

55 Baird D.D., Umbach D.M., Landsdell L., et al. Dietary intervention study to assess estrogenicitiy of dietary soy among post-menopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:1685-1690.

56 Song W.O., Chun O.K., Hwang I., et al. Soy isoflavones as safe functional ingredients. J Med Food. 2007;10(4):571-580.

57 Kurzer M.S. Phytoestrogen supplement use by women. J Nutr. 2003;133(6):1983S-1986S.

58 Tham D.M., Gardner C.D., Haskell W.L. Clinical review 97: Potential health benefits of dietary phytoestrogens: a review of the clinical, epidemiological, and mechanistic evidence. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83(7):2223-2235.

59 Guha N., Kwan M.L., Queensberry C.P., et al. Soy isoflavones and risk of cancer recurrence in a cohort of breast cancer survivors: the Life After Cancer Epidemology study. Treat. 2009;118(2):395-405.

60 Han K.K., Soares J.M.Jr., Haidar M.A., et al. Benefits of soy isoflavone therapeutic regimen on menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(3):389-394.

61 Maesta N., Nahas E.A., Nahas-Neto J., et al. Effects of soy protein and resistance exercise on body composition and blood lipids in post-menopausal women. Maturitas. 2007 Apr 20;56(4):350-358.

62 Murkies A.L., Lombard C., Strauss B.J., et al. Dietary flour supplementation decreases post-menopausal hot flushes: effect of soy and wheat. Maturitas. 1995;21:189-195.

63 Nahas E.A., Nahas-Neto J., Orsatti F.L., et al. Efficacy and safety of a soy isoflavone extract in post-menopausal women: a randomised, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Maturitas. 2007 Nov 20;58(3):249-258.

64 Basaria S., Wisniewski A., Dupree K., et al. Effect of high-dose isoflavones on cognition, quality of life, androgens, and lipoprotein in post-menopausal women. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009 Feb;32(2):150-155.

65 Knight D.C., Howes J.B., Eden J.A., et al. Effects on menopausal symptoms and acceptability of isoflavone-containing soy powder dietary supplementation. Climacteric. 2001;4(1):13-18.

66 Lethaby A., Marjoribanks J., Kronenberg F., et al. Phytoestrogens for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Oct 17(4), 2007. CD001395

67 Howes L.G., Howes J.B., Knight D.C. Isoflavone therapy for menopausal flushes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas. 2006 Oct 20;55(3):203-211.

68 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins. Clinical Management Guidelines for Obstetrician/Gynecologists: Use of Botanicals for the management of Menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(Suppl):1-11.

69 Low Dog T. Menopause: a review of botanical dietary supplements. Am J Med. 2005 Dec 19;118(Suppl 12B):98-108.

70 Geller S.E., Studee L. Soy and red clover for mid-life and aging. Climacteric. 2006 Aug;9(4):245-263.

71 Setchell K.D., Brown N.M., Desai P.B., et al. ioavailability, disposition, and dose-response effects of soy isoflavones when consumed by healthy women at physiologically typical dietary intakes. J Nutr. 2003;133:1027-1035.

72 Setchell K.D., Brown N.M., Lydeking-Olsen E. The clinical importance of the metabolite equol-a clue to the effectiveness of soy and its isoflavones. J Nutr. 2002;132:3577-3584.

73 Nedrow A., Miller J., Walker M., et al. Complementary and alternative therapies for the management of menopause-related symptoms: a systematic evidence review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(14):1453-1465.

74 Knight D.C., Howes J.B., Eden J.A. The effect of promensil™, an isoflavone extract, on menopausal symptoms. Climacteric. 1999;2:79-84.

75 Peter H.M., van de Weijer P.H.M., Barentsen Ronald. Isoflavones from red clover (Promensil) significantly reduce menopausal hot flush symptoms compared with placebo. Maturitas. 2002;42:187-193.

76 Jeri A.R., Romana C.D. The effect of isoflavone phytoestrogens in relieving hot flushes in Peruvian post-menopausal women. The Fem Patient. 2002;27:35-37.

77 Thompson Coon J.S., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. The role of red clover (Trifolium pratense) isoflavones in women’s reproductive health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Foc Altern Compl Ther. 2003;8:544.

78 Tice J.A., Ettinger B., Ensrud K., et al. Phytoestrogen supplements for the treatment of hot flashes: the Isoflavone Clover Extract (ICE) Study: a randomised controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(2):207-214.

79 Booth N.L., Piersen C.E., Banuvar S., et al. Clinical studies of red clover (Trifolium pratense) dietary supplements in menopause: a literature review. Menopause. 2006;13(2):251-264.

80 Hale G.E., et al. A double-blind randomised study on the effects of red clover isoflavones on the endometrium. Menopause. 2001;8(5):338-346.

81 Coon J.T., Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Trifolium pratense isoflavones in the treatment of menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine. 2007;14(2-3):153-159.

82 Umland E.M. Treatment strategies for reducing the burden of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(3 Suppl):14-19.

83 Geller S.E., Studee L. Botanical and dietary supplements for mood and anxiety in menopausal women. Menopause. 2007;14(3 Pt 1):541-549.

84 Kronenberg F., Fugh-Berman A. Complementary and alternative medicine for menopausal symptoms: a review of randomised, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(10):805-813.

85 Geller S.E., Studee L. Botanical and dietary supplements for menopausal symptoms: what works, what does not. J Womens Health. 2005;14(7):634-649.

86 Osmers R., Friede M., Liske E., et al. Efficacy and safety of isopropanolic black cohosh extract for climacteric symptoms. Obstet. Gynecol. 2005;105:1074-1083.

87 Kligler B. Black cohosh. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):114-116.

88 Huntley A. The safety of black cohosh (Actaea racemosa, Cimicifuga racemosa). Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2004;3(6):615-623.

89 Frei-Kleiner S., Schaffner W., Rahlfs V.W., et al. Cimicifuga racemosa dried ethanolic extract in menopausal disorders: a double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Maturitas. 2005 Aug 16;51(4):397-404.

90 Bai W., Henneicke-von Zepelin H.H., Wang S., et al. Efficacy and tolerability of a medicinal product containing an isopropanolic black cohosh extract in Chinese women with menopausal symptoms: a randomised, double-blind, parallel-controlled study versus tibolone. Maturitas. 2007 Sep 20;58(1):31-41.

91 Nappi R.E., Malavasi B., Brundu B., et al. Efficacy of Cimicifuga racemosa on climacteric complaints: a randomised study versus low-dose transdermal estradiol. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2005 Jan;20(1):30-35.

92 Oktem M., Eroglu D., Karahan H.B., et al. Black cohosh and fluoxetine in the treatment of post-menopausal symptoms: a prospective, randomised trial. Adv Ther. 2007 Mar-Apr;24(2):448-461.

93 Geller S.E., Shulman L.P., van Breemen R.B., et al. Safety and efficacy of black cohosh and red clover for the management of vasomotor symptoms: a randomised controlled trial. Menopause: The Journal of The North American Menopause Society. 16(6), 2009. pp. 000/000. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3181ace49b

94 Newton K.M., Reed S.D., LaCroix A.Z., et al. Treatment of vasomotor symptoms of menopause with black cohosh, multibotanicals, soy, hormone therapy, or placebo: a randomised trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006 Dec 19;145(12):869-879.

95 Pockaj B.A., Gallagher J.G., Loprinzi C.L., et al. Phase III double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled crossover trial of black cohosh in the management of hot flashes: NCCTG Trial N01CC1. J Clin Oncol. 2006 Jun 20;24(18):2836-2841.

96 Liske E. Physiological investigation of a unique extract of black cohosh: a 6-month clinical study demonstrates no systemic estrogenic effect. Journal of women’s health and gender-based medicine. 2002;2:163-174.

97 Ruhlen R.L., Haubner J., Tracy J.K., et al. Black cohosh does not exert an estrogenic effect on the breast. Nutr Cancer. 2007;59(2):269-277.

98 Rebbeck T.R., Troxel A.B., Norman S., et al. A retrospective case-control study of the use of hormone-related supplements and association with breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2007 Apr 1;120(7):1523-1528.

99 Zepelin H.H., Meden H., Kostev K., et al. Isopropanolic black cohosh extract and recurrence-free survival after breast cancer. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2007 Mar;45(3):143-154.

100 Chow E.C., Teo M., Ring J.A., et al. Liver failure associated with the use of black cohosh for menopausal symptoms. MJA. 2008;188(7):420-422.

101 Whiting P.W., Clouston A., Kerlin P. Black cohosh and other herbal remedies associated with acute hepatitis. Med J Aust. 2002;177:440-443.

102 Lontos S., Jones R.M., Angus P.W., et al. Acute liver failure associated with the use of herbal preparations containing black cohosh. Med J Aust. 2003;179(7):390-391.

103 Walji R., Boon H., Guns E., et al. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa [L.] Nutt.): safety and efficacy for cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(8):913-921.

104 Borrelli F., Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa): a systematic review of adverse events. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Nov;199(5):455-466.

105 Lieberman S. A review of the effectiveness of Cimicifuga Racemosa (Black Cohosh) for the Symptoms of Menopause. J Women’s Health. 1998;7:525-529.

106 Kanadys W.M., Leszczyńska-Gorzelak B., Oleszczuk J. Efficacy and safety of Black cohosh (Actaea/Cimicifuga racemosa) in the treatment of vasomotor symptoms–review of clinical trials. Ginekol Pol. 2008 Apr;79(4):287-296.

107 Borrelli F., Ernst E. Black cohosh (Cimicifuga racemosa) for menopausal symptoms: a systematic review of its efficacy. Pharmacol Res. 2008 Jul;58(1):8-14.

108 Uebelhack R., Blohmer J.U., Graubaum H.J., et al. Black cohosh and St. John’s wort for climacteric complaints: a randomised trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107(2 Pt 1):247-255.

109 Briese V., Stammwitz U., Friede M., et al. Black cohosh with or without St. John’s wort for symptom-specific climacteric treatment–results of a large-scale, controlled, observational study. Maturitas. 2007 Aug 20;57(4):405-414.

110 Chung D.J., Kim H.Y., Park K.H., et al. Black cohosh and St. John’s wort (GYNO-Plus) for climacteric symptoms. Yonsei Med J. 2007 Apr 30;48(2):289-294.

111 van Die M.D., Burger H.G., Bone K.M., et al. Hypericum perforatum with Vitex agnus-castus in menopausal symptoms: a randomised, controlled trial. Menopause. 2008 Sep 10.

112 Heyerick A., Vervarcke S., Depypere H., et al. A first prospective, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the use of a standardised hop extract to alleviate menopausal discomforts. Maturitas. 2006;54(2):164-175.

113 Rotem C., Kaplan B. Phyto-Female Complex for the relief of hot flushes, night sweats and quality of sleep: randomised, controlled, double-blind pilot study. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2007 Feb;23(2):117-122.

114 Pruthi S., Thompson S.L., Novotny P.J., et al. Pilot evaluation of flaxseed for the management of hot flashes. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2007 Summer;5(3):106-112.

115 Hirata J.D., Swiersz L.M., Zell B., et al. Does dong quai have estrogenic effects in post-menopausal women? A double-blind, placebo- controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 1997;68:981-986.

116 Chenoy R., Hussain S., Tayob Y., et al. Effect of oral gamolenic acid from evening primrose oil on menopausal flushing. BMJ. 1994;308:501-503.

117 Wiklund I.K., Mattsson L.A., Lindgren R., et al. Effects of standardised ginseng extract on quality of life and physiological parameters in symptomatic post-menopausal women: a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Swedish Alternative Medicine Group. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res. 1999;19:89-99.

118 Komesaroff P.A., Black C.V., Cable V., et al. Effects of wild yam extract on menopausal symptoms, lipids and sex hormones in healthy menopausal women. Climacteric. 2001;4:144-150.

119 Oh S.M., Chung K.H. Estrogenic activities of Ginkgo biloba extracts. Life Sci. 2004 Jan 30;74(11):1325-1335.

120 Papapetropoulos A.A. ginseng-derived oestrogen receptor beta (ERbeta) agonist, Rb1 ginsenoside, attenuates capillary morphogenesis. Br J Pharmacol. 2007 Sep;152(2):172-174.

121 Cho J., Park W., Lee S., et al. Ginsenoside-Rb1 from Panax ginseng C.A. Meyer activates estrogen receptor-alpha and -beta, independent of ligand binding. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004 Jul;89(7):3510-3515.

122 Lee Y.J., Jin Y.R., Lim W.C., et al. Ginsenoside-Rb1 acts as a weak phytoestrogen in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2003 Jan;26(1):58-63.

123 Herbs2000.com. Available: http://www.herbs2000.com/herbs/herbs_wild_yam.htm (accessed 9 March 2010).

124 Barton D.L., Loprinzi C.L., Quella S.K., et al. Prospective evaluation of vitamin E for hot flashes in breast cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(2):495-500.

125 Ziaei S., Kazemnejad A., Zareai M. The effect of vitamin E on hot flashes in menopausal women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2007;64(4):204-207.

126 Carroll D.G. Nonhormonal therapies for hot flashes in menopause. Am Fam Physician. 2006;73(3):457-464.

127 Avis N.E., Legault C., Coeytaux R.R., et al. A randomised, controlled pilot study of acupuncture treatment for menopausal hot flashes. Menopause. 2008 Jun 2.

128 Frisk J., Carlhäll S., Källström A.C., et al. Long-term follow-up of acupuncture and hormone therapy on hot flushes in women with breast cancer: a prospective, randomised, controlled multicenter trial. Climacteric. 2008;11(2):166-174.

129 Filshie J., Bolton T., Browne D., et al. Acupuncture and self acupuncture for long-term treatment of vasomotor symptoms in cancer patients-audit and treatment algorithm. Acupunct Med. 2005;23(4):171-180.

130 Deng G., Vickers A., Yeung S., et al. Randomised, controlled trial of acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5584-5590.

131 Hervik J., Mjåland O. Acupuncture for the treatment of hot flashes in breast cancer patients. a randomised, controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 Oct 7.

132 Lee M.S., Shin B.C., Ernst E. Acupuncture for treating menopausal hot flushes: a systematic review. Climacteric. 2009 Feb;12(1):16-25.

133 Cho S.H., Whang W.W. Menopause. Acupuncture for vasomotor menopausal symptoms: a systematic review. 2009 May 6.

134 Lee M.S., Kim K.H., Choi S.M., et al. Acupuncture for treating hot flashes in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009 Jun;115(3):497-503. Epub 2008 Nov 4

135 McBane S.E. Easing vasomotor symptoms: Besides HRT, what works? JAAPA. 2008;21(4):26-31.