Meniscectomy and Meniscal Repair

Morgan L. Fones, George F. Rick. Hatch, III and Timothy Hartshorn

Although meniscal repair was introduced more than 100 years ago, only within the past 10 to 20 years has the meniscus successfully outlived its characterization as a “functionless remain of leg muscle.1” Only a few years ago it was standard practice to excise the meniscus with impunity because of the perception that it played little role in the function of the knee. Fairbanks2 called attention to the frequency of degenerative changes after removal of the meniscus and stimulated a new era of research into the anatomy and function of this poorly understood structure. Researchers eagerly investigated the role of the meniscus in load transmission and joint nutrition, and soon the pendulum of orthopedic popular opinion swung in the direction of determining new ways to preserve the injured meniscus.

With the advent of arthroscopic surgery, partial meniscectomy rapidly supplanted total meniscectomy, and research continued to determine the healing capacity of the torn meniscus. From these efforts, meniscal repair has evolved as a successful technique. Ultimately, recognition of the intact meniscus as a crucial factor in normal knee function has led to widespread acceptance of preservation of torn menisci through partial meniscectomy or repair.

Surgical Indications and Considerations

When assessing the suitability of a meniscal tear for repair, the surgeon must consider several factors: patient age; chronicity of the injury; type, location, and length of the tears (the blood supply of the meniscus exists primarily at the peripheral 10% to 25%); and associated ligamentous injuries.3 The perfect candidate for a meniscal repair is a young individual with an acute longitudinal peripheral tear of the meniscus that is 1 to 2 cm long, to be repaired in conjunction with an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction. Success rates for meniscal repairs in conjunction with ACL reconstruction has been as high as 90% compared with 75% for isolated meniscus repairs.4 It appears that the medial meniscus is more suitable for repair than the lateral meniscus. Shelbourne and Dersam5 performed a repair of partially excised lateral meniscus tears. The surgery was performed in conjunction with ACL reconstruction and the repair was performed using an inside-outside technique. They noted that although no significant statistical difference existed between the two groups (International Knee Documentation Committee grade), the partial meniscectomy group had more pain.5 Shelbourne and Heinrich6 also noted that certain types of lateral meniscus tears could be successfully treated with abrasion and trephination or just left in situ. Noyes and Barber-Westin4,7 studied two different age groups and their response to meniscus repair. They used an inside-outside technique with a majority of the patients undergoing concomitant ACL reconstruction. In looking at the outcomes, 87% of the older (over 40 years old) group, and 75% of the younger (under 20 years old) group were asymptomatic for medial compartment symptoms. They also noted significant improvement in outcomes when the repair was done in conjunction with an ACL reconstruction. Age may not be as significant a factor as the type of tear (degenerative or nondegenerative).8 The current trend appears to lean toward the preservation of the meniscus whenever possible based on the patient’s current and future activity levels. More research is being performed looking at the long-term results and categorizing further the indications for meniscus repair.9 Outside of these parameters, little consensus exists regarding the relative indications for meniscal repair.

The arthroscopic surgeon should be prepared to perform meniscal repair at the time of any knee arthroscopy. The identification of reparable menisci is usually not possible preoperatively, but often magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can help demonstrate the location of tears.

Four techniques for repair currently exist:

Each of these techniques has advantages and disadvantages; application of individual techniques is largely a matter of individual preference.

Surgical Procedure

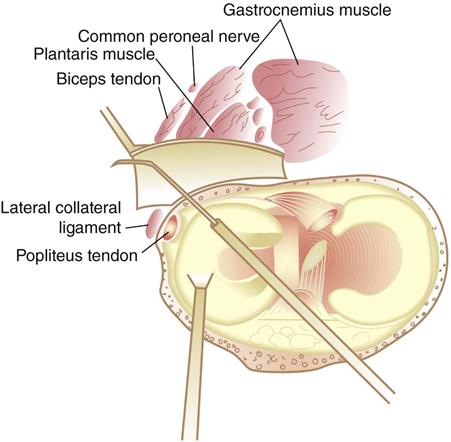

Open Meniscal Repair

Open meniscal repair (Fig. 24-1) is the oldest technique for meniscal repair and has been popularized by Dr. Ken DeHaven.10 It has a good record of success, even at 1-year follow-up.11 Open meniscal repairs are best suited for extremely peripheral tears. DeHaven still advocates routine arthroscopic evaluation before considering open repair. The arthroscope is removed from the joint and the knee is prepared. After exposing the capsule through a longitudinal incision, the surgeon prepares the meniscal rim and capsular attachment, and places vertically oriented sutures at 3- to 4-mm intervals. The incision is closed in a layered fashion. Long-term follow-up has shown success rates of 70% to 79%.12–14

Inside-Out Meniscal Repair

The inside-out meniscal repair technique was popularized by Henning15 in the early 1980s and is the most popular technique for meniscus repair. The surgeon uses long, thin cannulas to allow placement of vertical or horizontal sutures. After identifying the tear arthroscopically, he or she prepares the tear by using a meniscal rasp to create a better biologic environment for healing. A small posterior incision is carried down to the capsule, and sutures are placed arthroscopically using specially designed long Keith needles to pass the suture. The assistant protects the popliteal structures with a retractor while grasping the suture needles. After placing all sutures, the surgeon ties them over the capsule. Success rates have been noted to be 75% to 88%.14,16

Outside-In Meniscal Repair

The outside-in meniscal repair technique allows suture placement using an 18-gauge spinal needle placed across the tear from outside the joint to inside. Absorbable polydioxanone suture17 is passed through the needle into the joint; it is secured with a mulberry knot tied to the end of the sutures. These sutures are tied to adjacent sutures at the end of the procedure over the joint capsule; separate small incisions are made for each pair of sutures. Morgan and colleagues18 noted an 84% success rate and found the primary reason for failure was an associated ACL deficiency.

All-Inside Meniscal Repair

All-inside meniscal repair allows the meniscus to be repaired without any additional incisions outside the knee. This is truly an all-arthroscopic technique. It is popular because it avoids additional incisions and therefore diminishes neurovascular risk and decreases operative time.14 Success rates have been noted as high as 90%.14,19

All-inside meniscal repair can be accomplished with either suture or biodegradable “darts.20” The suture technique is accomplished using a specially designed cannulated suture hook to pass suture through both sides of the tear. The sutures are then tied arthroscopically using a knot pusher.

The biodegradable darts are passed across the tear using specially designed cannulas. After preparing the torn meniscal surface, the surgeon reduces the tear and holds it in place with a cannula. A thin cutting instrument is used to make a pathway across the meniscal tear, and the biodegradable dart is passed through the same cannula, fixing the tear. The darts generally completely resorb by 8 to 12 weeks.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

![]() Limited research is available regarding physical therapy protocols after meniscus repair and long-term outcomes. Clinic protocols vary with the degree of weight bearing, duration of immobilization, control of range of motion (ROM), and time frame for a return to sports or work. Recent studies have shown the success rates after accelerated rehabilitation programs to be similar to those in conservative rehabilitation programs. These studies found no statistically significant difference in success and repair failure rates between groups using conservative or accelerated programs. The hallmarks of accelerated programs are early full weight-bearing tolerance, unrestricted ROM, and return to pivoting sports.21–23 Recent studies have shown that dynamic loading can help meniscal repair healing in inflammatory environments.24

Limited research is available regarding physical therapy protocols after meniscus repair and long-term outcomes. Clinic protocols vary with the degree of weight bearing, duration of immobilization, control of range of motion (ROM), and time frame for a return to sports or work. Recent studies have shown the success rates after accelerated rehabilitation programs to be similar to those in conservative rehabilitation programs. These studies found no statistically significant difference in success and repair failure rates between groups using conservative or accelerated programs. The hallmarks of accelerated programs are early full weight-bearing tolerance, unrestricted ROM, and return to pivoting sports.21–23 Recent studies have shown that dynamic loading can help meniscal repair healing in inflammatory environments.24

Several crucial factors must be considered before initiating a rehabilitation program. These factors influence the speed and aggressiveness of the rehabilitation program. The size of the tear, repair stabilization technique, suture material, number of sutures, and location of the meniscal repair influence initial postoperative weight-bearing tolerance, ROM, and exercise restrictions. Other factors to consider before initiating a rehabilitation program include degenerative pathology in the weight-bearing articulations or patellofemoral joint, previous patella dysfunction, concomitant injuries, possible joint laxity (i.e., ACL deficiency or reconstruction, medial collateral ligament injury), and severe kinetic chain movement dysfunctions proximally or distally that alter knee alignment and forces. These injuries do not necessarily indicate a potentially unsatisfactory result, but accommodations may be required in the protocol to accommodate the effects of these pathologies. Barber and Click21 evaluated the results of 65 meniscal repairs in patients who underwent an accelerated rehabilitation program. Successful meniscal healing occurred in 92% of patients with a concomitant ACL reconstruction, compared with 67% of patients with ACL-deficient knees and 67% of patients with meniscal pathology alone.

An understanding of the clinical implications of knee and meniscus biomechanics helps guide the therapist through the rehabilitation process. Communication among all rehabilitation team members—the physician, therapist, patient, family, and coach—is crucial to a successful rehabilitation outcome. Most importantly, the meniscal repair rehabilitation protocol must be individually tailored to the patient’s needs.

The rehabilitation process can be broken down into three phases: initial, intermediate, and advanced. These phases may overlap and should be based on objective and functional findings rather than time.

The early phase of the rehabilitation program should emphasize decreasing postoperative inflammatory reaction, restoring controlled ROM, and encouraging early weight bearing as tolerated. Exercise intensity is increased in the later phases of rehabilitation. Closed kinetic chain exercises are progressed through a variety of positions, from simple linear movements to complex multidirectional, multiplanar motions. The final phase of treatment is directed toward return to normal activity (sport or work).

The length of rehabilitation varies among patients. Treatments may be equally distributed among each of the phases of rehabilitation if the number of patient visits must be managed. Fewer treatments are required in the initial phases of rehabilitation if swelling and pain are adequately controlled and ROM is progressing without complications.

Preoperative Care

Ideally the patient should be seen at a preoperative visit, which includes a brief clinical evaluation to record baseline physical data and identify potential latent biomechanical deficits. The evaluation format encompasses a subjective history as outlined in Maitland,25 and objective data are gathered primarily to record baseline measurements. The lower extremity (LE) is evaluated as a functional unit. Strength and ROM are recorded for the hip, knee, ankle, and foot. Foot mechanics also are evaluated for any biomechanical faults that may lead to excessive tibial motions in the frontal or transverse planes. For example, pes planus has the potential to drive tibial internal rotation, creating a mechanism for excessive transverse friction at the knee joint. In addition, hip abduction and external rotation strength need to be examined to avoid excessive femoral adduction and internal rotation distally. Reassessment continues postoperatively with each progression of weight bearing. Girth measurements also are taken about the knee. The remainder of the preoperative visit should include instruction in proper use of crutches, education regarding ROM (heel slides with a 30-second hold for 10 repetitions), instruction in antiembolic exercises (ankle pumps with a 30-second hold for 10 repetitions), and prescription of LE strengthening exercises in the form of isometrics (quadriceps sets, hamstring sets, and cocontraction of quadriceps and hamstrings; all three exercises should be held for 10 seconds for 10 to 20 repetitions) and active range of motion (AROM) of the hip (working the adductors, abductors, and external rotators for 10 to 20 repetitions). Cryotherapy and elevation (for 15 to 30 minutes) and compression wrapping should be reviewed for postoperative pain and swelling management. Depending on individual clinic and physician preference, the patient may be instructed in the use of electrical stimulation (ES). The patient should be instructed in activities of daily living, such as bathing and dressing, as appropriate. Home exercises are to be performed three times a day until return for the initial postoperative physical therapy evaluation.

Phase I (Initial Phase)

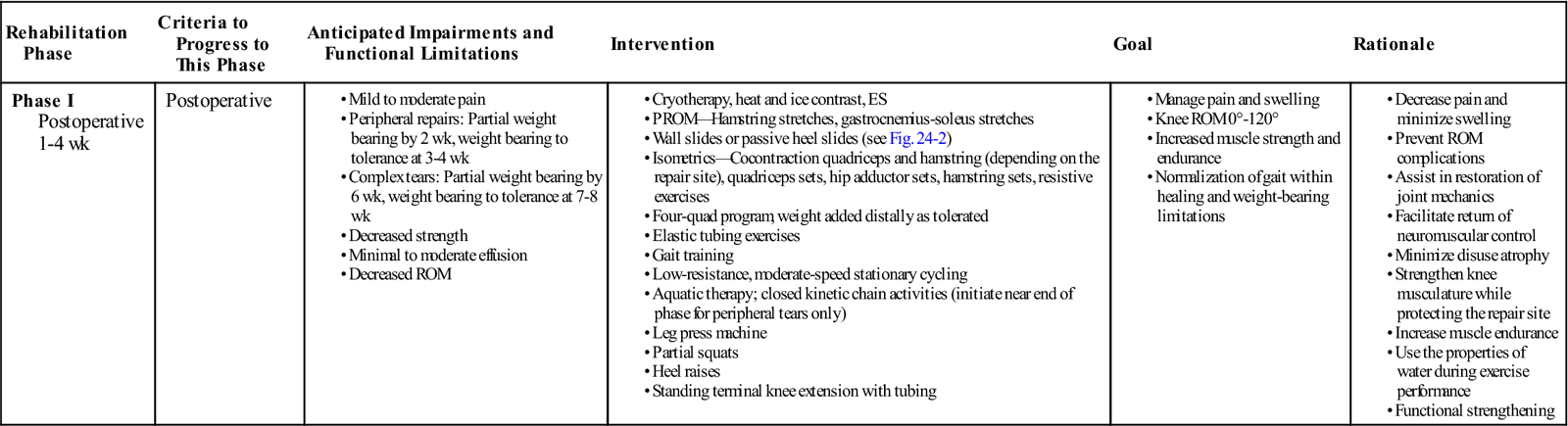

TIME: 1 to 4 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Manage pain and swelling, increase ROM and strength, increase weight-bearing activities and prevent excessive loads/stresses through the joint surfaces (Table 24-1)

TABLE 24-1

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase I Postoperative 1-4 wk |

Postoperative |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

ES, Electrical stimulation; PROM, passive range of motion; ROM, range of motion.

The patient is typically seen for physical therapy 4 to 7 days after surgery. He or she may complain of mild to moderate pain, swelling, impaired balance, and decreased weight-bearing tolerance. The patient may or may not be using pain medication.

![]() Generally, patients undergoing partial or total meniscectomy may be weight bearing as tolerated immediately or soon after surgery whereas those undergoing repair are usually non–weight bearing (NWB) or partial weight bearing (PWB) with crutches for a period of 2 to 6 weeks. Noyes recommends 4 weeks of PWB for complex and avascular tears, with up to 6 weeks of toe touch weight bearing when the patient has a radial tear.26 Tibiofemoral loads induce a circumferential stress (so-called “hoop stress”) in the meniscus, which would distract the radial tear margins.27 Based on physician preference, the patient may have a postoperative hinged knee brace, which will either be statically locked at a particular setting for 7 to 10 days or set between certain parameters to allow for immediate postoperative ROM. Meniscal repairs in the “red-red zone” and larger peripheral repairs may be braced up to 90° for up to 14 days. “White zone” repairs may be braced at 20° to 70°. Extension is increased to 0°, and flexion is increased to 90° after 7 to 10 days as healing allows.

Generally, patients undergoing partial or total meniscectomy may be weight bearing as tolerated immediately or soon after surgery whereas those undergoing repair are usually non–weight bearing (NWB) or partial weight bearing (PWB) with crutches for a period of 2 to 6 weeks. Noyes recommends 4 weeks of PWB for complex and avascular tears, with up to 6 weeks of toe touch weight bearing when the patient has a radial tear.26 Tibiofemoral loads induce a circumferential stress (so-called “hoop stress”) in the meniscus, which would distract the radial tear margins.27 Based on physician preference, the patient may have a postoperative hinged knee brace, which will either be statically locked at a particular setting for 7 to 10 days or set between certain parameters to allow for immediate postoperative ROM. Meniscal repairs in the “red-red zone” and larger peripheral repairs may be braced up to 90° for up to 14 days. “White zone” repairs may be braced at 20° to 70°. Extension is increased to 0°, and flexion is increased to 90° after 7 to 10 days as healing allows.

On the first postoperative visit a comprehensive evaluation is performed, with the physical therapist collecting the new objective data and reviewing and updating the previous subjective data.25 Subjective data that need to be reviewed postoperatively include medication usage, sleep pattern, pain levels at rest and during activity, and aggravating and easing factors. In addition, the therapist should review the postoperative report dictated by the operating surgeon that describes the extent and nature of the repair, as well as any unique patient-specific postoperative instructions. Goals and rehabilitation expectations are established and reviewed with the patient during the initial visit.

The new and updated objective and clinical data should include visual examination, gait assessment, ROM measurement, strength assessment, palpation, and girth measurement (as described in the section on the preoperative initial visit). Visual observation should focus on areas of atrophy, in particular the quadriceps and gastrocnemius; healing status of incision sites; and swelling about the knee joint and distal LE. Depending on the patient’s weight-bearing status or tolerance, gait assessment is either brief or detailed. Gait assessment should focus on proper mechanics and weight-bearing tolerance. If the patient is NWB or PWB, the assessment is brief and focuses primarily on safety, correct mechanics (with crutches), and includes a discussion regarding weight-bearing restrictions. If the patient does not have weight-bearing limitations and has good gait tolerance, then a more detailed assessment of gait can be made. The patient’s ability to ambulate with normal mechanics throughout each phase of gait is very important and should be assessed. Remedial corrective actions are required to decrease potentially harmful loading onto healing structures. Typically patients require cueing to avoid hip external rotation during the stance phase, because this puts abnormal stresses through the knee, ankle, and foot. Crutches should be used throughout the initial phase of treatment until adequate strength, ROM, and normal gait mechanics are achieved. Static and dynamic foot function (as related to normal gait mechanics) continues to be assessed during this phase of rehabilitation. Dysfunctions must be addressed to decrease abnormal tensile or compressive force affecting healing of the meniscus repair.

Flexibility of the hip musculature, hamstring, and gastrocnemius-soleus complex should be assessed. The patellofemoral joint should be assessed, especially if the patient reports previous or present patella symptoms. Patella tracking and glides are part of this assessment. Joint mobilization or patellofemoral taping may be helpful in mitigating these symptoms.28 All major muscle groups in the LE should be assessed bilaterally for strength capacity. In addition, visible observation and palpation of the quadriceps during an isometric quad set or straight leg raise (SLR) can give the clinician insight into the patient’s ability to be safe and secure in an upright position. The remaining LE musculature should be assessed, with the therapist identifying any potential weakness that may alter normal closed kinetic biomechanics and therefore increase tensile or compressive forces across the meniscus repair site.

No standard method has been established for assessing girth about the knee joint. Consistency among the team members providing patient care is important when reassessing the patient’s condition. Atrophy as measured by girth measurements is not diagnostic of weakness or atrophy in a specific muscle group. Circumference measurement assesses girth of all muscle and joint structures underlying the measurement area. Typical measurement sites for a bilateral comparison include the midpatella, 5 and 10 cm above the knee joint and 5 and 10 cm below the knee joint.

Treatment is initiated after the clinical evaluation is completed (see Table 24-1). Initial phase treatment goals are to decrease pain and manage swelling, restore ROM, increase muscle strength and endurance, and normalize gait within healing and weight-bearing limitations.

Pain and Edema Management

Minimal to moderate effusion will likely be evident at the evaluation. Modalities such as cryotherapy, heat and ice contrast, and ES can be used to decrease pain and swelling.29–31 Instructions in home use of cryotherapy, compression wrapping, and elevation as discussed in the section on preoperative management is initiated for postoperative pain and swelling. The importance of home cryotherapy cannot be overemphasized. The study of Lessard and colleagues30 on the use of cryotherapy after meniscectomy found statistically significant differences between groups with and without postoperative cryotherapy. Patients reported decreased pain ratings per the McGill pain questionnaire, decreased medication consumption, improved exercise compliance, and improved weight-bearing status.

Range of Knee Motion and Flexibility

Restoration of ROM is vital to a return to the patient’s prior level of function. Typically on initial evaluation, the patient exhibits a loss of extension of 5° to 10°; flexion ROM is typically 70° to 90°. The patient usually exhibits a guarded end feel with motion improving with repetition. The time parameter to achieve full ROM is longer with meniscal repair than it is in partial arthroscopic meniscectomies. Although early restoration of ROM is important to normalize joint function, the healing process of the meniscus repair dictates caution, especially with full circumferential peripheral repairs.

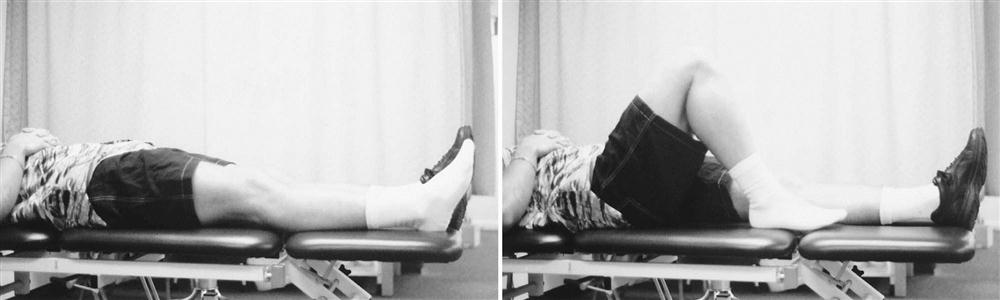

![]() Any exercises used to increase ROM should not be forced because of the risk of stressing healing repair sites. Wall slides, sitting passive knee flexion, or passive heel slides (Fig. 24-2) may be used to increase knee flexion. ROM exercises are to be performed within pain tolerance, held at least 30 seconds, and repeated as tolerated (generally 5 to 10 times). As part of the home exercise program, ROM activity can be repeated three to five times per day.

Any exercises used to increase ROM should not be forced because of the risk of stressing healing repair sites. Wall slides, sitting passive knee flexion, or passive heel slides (Fig. 24-2) may be used to increase knee flexion. ROM exercises are to be performed within pain tolerance, held at least 30 seconds, and repeated as tolerated (generally 5 to 10 times). As part of the home exercise program, ROM activity can be repeated three to five times per day.

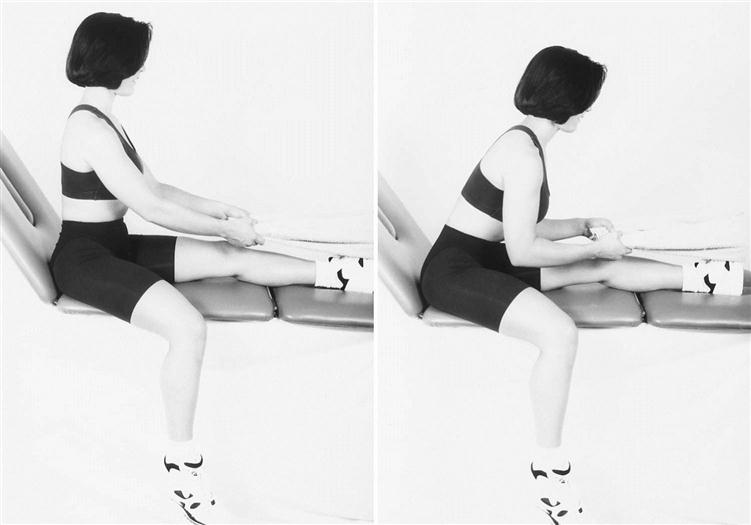

Appropriate remedial flexibility exercises can be implemented as tolerated in this phase, with the patient avoiding forced knee flexion and rotation about the knee joint. Patients should perform slow static stretches, avoiding ballistic movements, to maintain control of the lower limb and minimize the chance of affecting the healing meniscus repair.32,33 Hamstring and gastrocnemius-soleus flexibility exercises are typically indicated at this time. Stretches should be held at least 30 seconds and repeated 5 times, three times a day. Stretches should be sustained and passive in nature, allowing the patient or therapist to control knee joint motions, avoiding potential complications from ballistic type of stretching.34 The hamstring group can be stretched passively using supine position. A towel can be used to assist with the raising of the leg (Fig. 24-3). The gastrocnemius-soleus can be stretched using a towel or strap in the early phases of rehabilitation. Progression to stretching of the hip musculature and quadriceps can be performed as the patient’s increase in knee ROM dictates. The knee needs to be kept in a relative neutral position to avoid any rotational or compressive forces on the repaired meniscus site. Standing gastrocnemius-soleus stretching can be initiated as weight-bearing tolerance increases.

![]() It is important to keep the foot in a neutral position to avoid any tibial rotation caused by supination or pronation, which may increase knee joint compression and tensile forces across the repaired meniscal site.

It is important to keep the foot in a neutral position to avoid any tibial rotation caused by supination or pronation, which may increase knee joint compression and tensile forces across the repaired meniscal site.

Patients who develop limitations in either flexion or extension of the surgical knee require manual patella mobilizations (Fig. 24-4) and home exercises for aggressive long static stretches. Patella mobilizations should be done in the superior, inferior, medial, and lateral directions and are vital to achieving full ROM. In addition, the patient is instructed in prolonged flexibility stretches. For a flexion contracture, the foot and ankle are propped up on a rolled towel, allowing the knee to drop into full extension. Then a 5- to 10-lb weight is placed on top of the knee for 10 minutes. This is done daily 6 to 8 times. Flexion exercises can be done in the seated position with the other leg providing overpressure. Other ways are to use a rolling chair, a supine wall slide, or a quadriceps stretch.

Strengthening

Initial strengthening is performed as tolerated in open-chain positions. Closed kinetic strengthening can be initiated, depending on the weight-bearing status and tolerance of the patient. All strengthening exercises should be closely monitored for potential adverse reactions and increased pain or swelling.

Strengthening exercises for all LE musculature are initiated with an emphasis on restoration of quadriceps muscle function to minimize potential patellofemoral dysfunction. Isometric exercises should be held for 10 seconds and performed for 10 to 20 repetitions. Quadriceps sets can be performed within the patient’s tolerance. A small towel may be required under the posterior aspect of the knee if the patient lacks full extension or if muscle setting in full extension is painful to the knee joint area. The patient is instructed to extend at the hip while tightening the quadriceps muscle, straightening the knee as tolerated. This exercise also may help restore knee extension. The towel should be removed as knee extension increases or becomes less painful. Adductor isometric contractions can be performed isolated or in conjunction with quadriceps sets.35

Hamstring isometrics can be performed; they should initially be performed at a submaximal level, with vigor increased based on patient tolerance and response.

![]() Caution should be exhibited when performing hamstring exercises early in rehabilitation, especially with larger peripheral rim or posterior horn meniscus repairs. Active knee flexion pulls the medial and lateral meniscus posterior. Because the lateral meniscus is more loosely attached, it can migrate posteriorly as much as 1 cm as a result of pull from the popliteus muscle. The medial meniscus may move a few millimeters via the posterior attachment to the joint capsule and influence from the nearby semimembranosus attachment.3 Cocontraction isometrics of the quadriceps and hamstrings may be used in the first 2 to 4 weeks in patients with the aforementioned repairs to allow adequate meniscal healing.36

Caution should be exhibited when performing hamstring exercises early in rehabilitation, especially with larger peripheral rim or posterior horn meniscus repairs. Active knee flexion pulls the medial and lateral meniscus posterior. Because the lateral meniscus is more loosely attached, it can migrate posteriorly as much as 1 cm as a result of pull from the popliteus muscle. The medial meniscus may move a few millimeters via the posterior attachment to the joint capsule and influence from the nearby semimembranosus attachment.3 Cocontraction isometrics of the quadriceps and hamstrings may be used in the first 2 to 4 weeks in patients with the aforementioned repairs to allow adequate meniscal healing.36

Short arc quadriceps exercises can be added if the patient tolerates end-range extension movement. Resistance should be added carefully, with the therapist remaining mindful of the role of the quadriceps in pulling the meniscus anteriorly by way of the meniscopatellar ligament, as well as the anterior posterior compressive force exerted by the femoral condyle during knee extension.28 Another effective open chain exercise for the quadriceps is active assisted knee extension in sitting from 90° to 30°. An open-chain (SLR) “4 quad” program (i.e., four quadrants: hip flexion, abduction, adduction, and extension) can be initiated with the knee fully extended if the patient has adequate LE and quadriceps control. The “4 quad” program is a series of SLR exercises held for 10 seconds and 10 to 20 repetitions:

Progression of this program is based on patient signs and symptoms. Resistance can be added distally as tolerated. The DeLorme strength progression protocol37 can be used, with gradual increases in resistance based on patient signs and symptoms.

Weight-bearing status and patient tolerance may limit the ability to strengthen the distal musculature. Strengthening of the ankle can be aided by exercises using elastic tubing; the patient should perform three sets of 10 to 20 repetitions. Ankle movements of dorsiflexion, plantar flexion, inversion and eversion, and hip proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) patterns (with the knee extended) can be performed to the patient’s tolerance. As with other healing collagen structures, controlled tensile and compressive loading may assist in scar conformation, revascularization, and improvement in the tensile properties of the meniscal repair through the maturation process.38 Gradual progression and reassessment of activity is crucial.

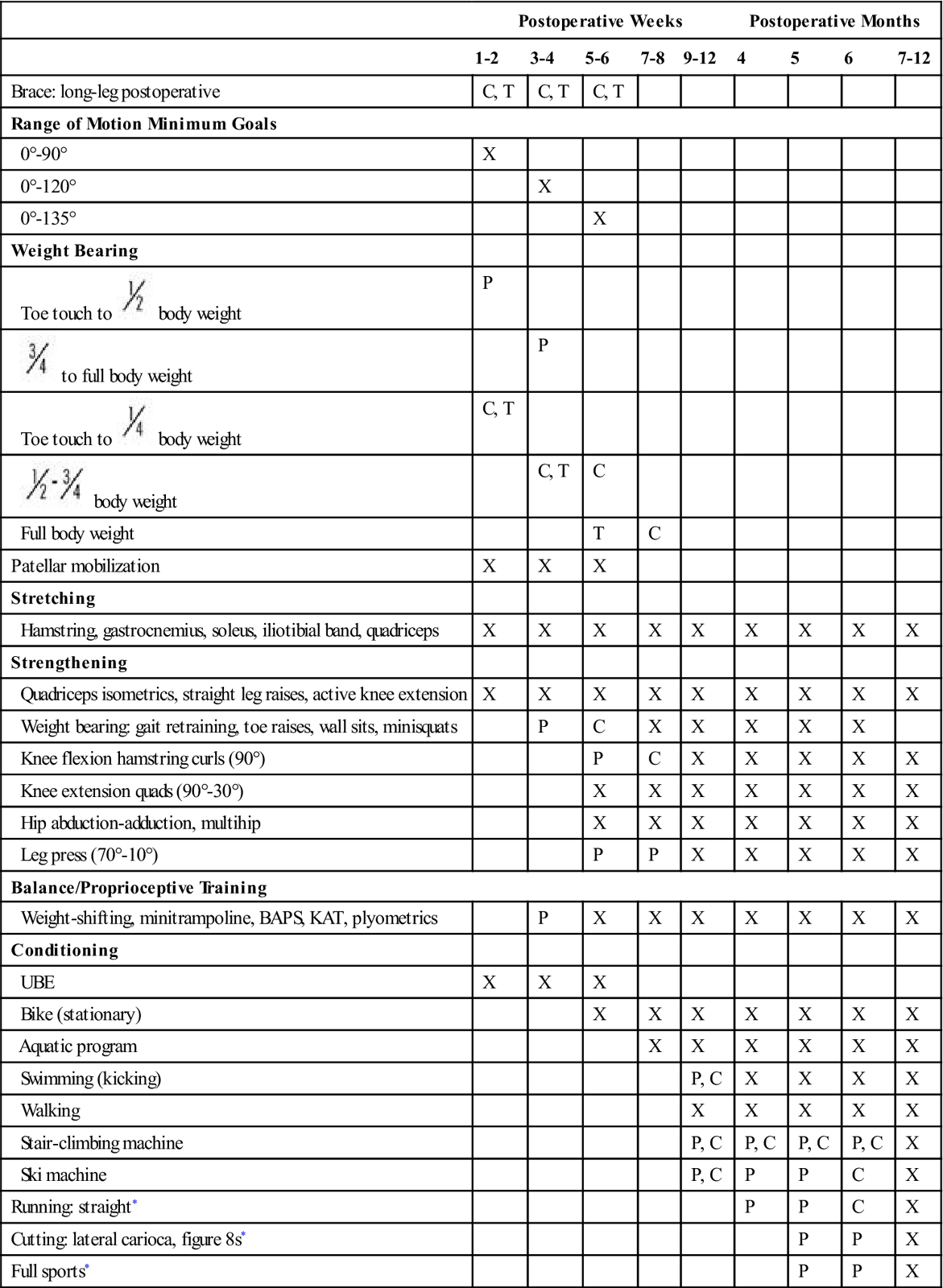

When initiating any of the closed kinetic chain exercises, the patient must keep the knee and LE in a neutral position. In normal gait the compressive forces on the knee joint may be two to three times normal body weight. The meniscus assumes 40% to 60% of the weight-bearing load. Variations in knee joint angulation or rotation can increase the force across the meniscus 25% to 50%.1 Variations in foot mechanics that cause rotation or angulation of the knee into varus or valgus can have potentially significant effects on meniscal compressive and tensile forces that may affect the repair site. As a result, some physicians recommend initiating closed-chain exercises only for peripheral tears during this phase while waiting until phase II (5 to 11 weeks) for complex tears39 (Table 24-2).

TABLE 24-2

< ?comst?>

| Postoperative Weeks | Postoperative Months | ||||||||

| 1-2 | 3-4 | 5-6 | 7-8 | 9-12 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7-12 | |

| Brace: long-leg postoperative | C, T | C, T | C, T | ||||||

| Range of Motion Minimum Goals | |||||||||

| 0°-90° | X | ||||||||

| 0°-120° | X | ||||||||

| 0°-135° | X | ||||||||

| Weight Bearing | |||||||||

Toe touch to  body weight body weight |

P | ||||||||

to full body weight to full body weight |

P | ||||||||

Toe touch to  body weight body weight |

C, T | ||||||||

body weight body weight |

C, T | C | |||||||

| Full body weight | T | C | |||||||

| Patellar mobilization | X | X | X | ||||||

| Stretching | |||||||||

| Hamstring, gastrocnemius, soleus, iliotibial band, quadriceps | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Strengthening | |||||||||

| Quadriceps isometrics, straight leg raises, active knee extension | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Weight bearing: gait retraining, toe raises, wall sits, minisquats | P | C | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Knee flexion hamstring curls (90°) | P | C | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Knee extension quads (90°-30°) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Hip abduction-adduction, multihip | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Leg press (70°-10°) | P | P | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Balance/Proprioceptive Training | |||||||||

| Weight-shifting, minitrampoline, BAPS, KAT, plyometrics | P | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Conditioning | |||||||||

| UBE | X | X | X | ||||||

| Bike (stationary) | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Aquatic program | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| Swimming (kicking) | P, C | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Walking | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Stair-climbing machine | P, C | P, C | P, C | P, C | X | ||||

| Ski machine | P, C | P | P | C | X | ||||

| Running: straight* | P | P | C | X | |||||

| Cutting: lateral carioca, figure 8s* | P | P | X | ||||||

| Full sports* | P | P | X | ||||||

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>*< ?comst1?>< ?comen1?>Return to running, cutting, and full sports based on multiple criteria. Patients with noteworthy articular cartilage damage are advised to return to light recreational activities only.

Partial weight-bearing, closed kinetic chain activities using leg press or inclined squat machines, partial squats, and heel raises can be initiated later in the initial phase. Standing terminal knee extension with tubing can be added to increase quadriceps strength and control with full weight bearing.

Aquatic therapy is an additional treatment option during the third and fourth week of the initial phase, especially if the patient has limited weight bearing and cannot tolerate traditional therapy because of pain.40

Balance and Proprioceptive Training

When patients achieve PWB, balance and proprioceptive training can begin. Crutches are used to assist during these exercises. Initially, the patients begin with tolerable weight shifts in the sagittal and frontal planes. Tandem balancing can also be initiated during the partial weight-bearing phase. Gait training with small obstacles like water cups can help develop adequate stance phase stability, symmetry between the surgical and contralateral limbs, and improved proprioception. Some patients may be able to progress to a single-leg balance exercise, where the knee is held at 20° to 30° of flexion. Different surfaces can be added as needed.

Conditioning

A conditioning program can be initiated 2 to 4 weeks postoperatively with an upper body ergometer. Low-resistance, moderate-speed stationary cycling can be initiated when knee flexion ROM is around 110°. Toe clips may be optional if hamstring activity is to be minimized because of the location of the repair. Progression is determined by the patient’s tolerance to stationary cycling. The goal of initial phase cycling is to increase muscle endurance.

Complications in the initial phase of treatment include persistent pain and swelling, arthrofibrosis, adhesions at the porthole sites, patella tendonitis, and patellofemoral pain. Activity modification, use of modalities, heat and cold contrast, cryotherapy, and ES may be helpful in decreasing pain and swelling. Adhesion of the porthole sites within the distal fat pads may cause painful limitation of knee flexion and active knee extension. Ultrasound or phonophoresis, along with soft tissue mobilization of incision sites, may be helpful in mitigating distal patella symptoms. Assessment of patellofemoral mechanics (active and passive) is an ongoing process. Patellofemoral taping should be used to control pain and dysfunction.41

ROM gradually increases during the initial phase of treatment, approaching full ROM by the end of this phase. Passive and dynamic splints may be helpful in gaining ROM if the joint does not respond to conservative treatment. ![]() Initiation of vigorous stretching or knee joint mobilization should be discussed with the patient and physician. The therapist should be aware of knee joint symptoms, pain, and swelling as attempts to increase ROM (especially knee flexion) continue.

Initiation of vigorous stretching or knee joint mobilization should be discussed with the patient and physician. The therapist should be aware of knee joint symptoms, pain, and swelling as attempts to increase ROM (especially knee flexion) continue.

In addition, the therapist should be cognizant of and recognize meniscus lesion signs and symptoms. These include persistent joint effusion, joint line pain, and locking or giving way of the knee (as opposed to buckling or weakness from decreased LE or quadriceps strength).

If activity modification and use of modalities does not improve the patient’s symptoms and objective findings, or if the patient exhibits classic signs of a meniscus tear, then referral to the physician is indicated.

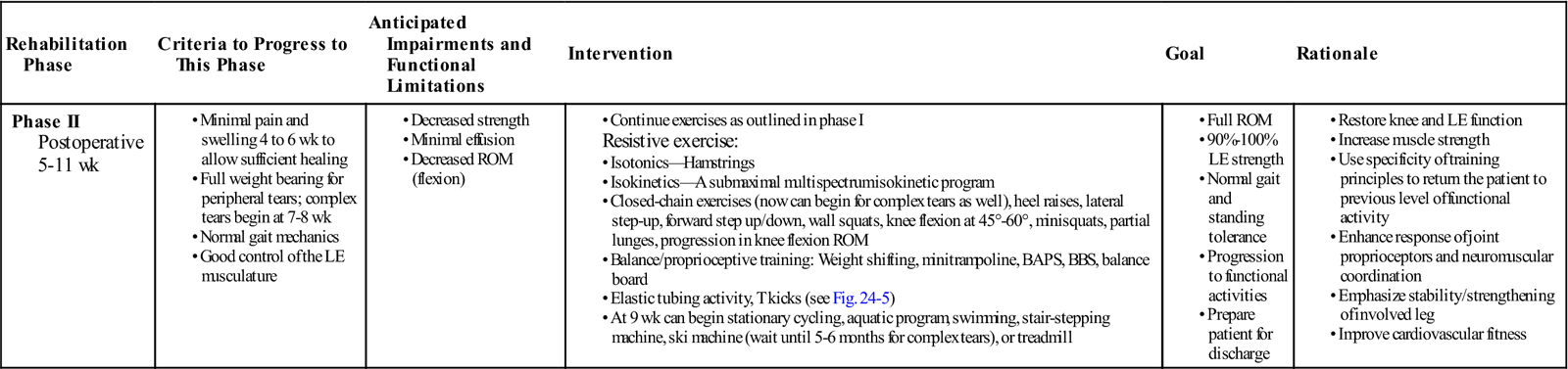

Phase II (Intermediate Phase)

TIME: 5 to 11 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Gain full ROM and 90% to 100% strength, progress functional activities, progress to gym program (Table 24-3)

TABLE 24-3

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase II Postoperative 5-11 wk |

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Objective findings rather than time ranges give an indication of progression into the intermediate phase of rehabilitation. In general this phase occurs around 4 to 6 weeks, in part based on improved patient signs and symptoms but also because enough time has elapsed to allow sufficient healing of the meniscal repair. This phase lasts until the patient is ready to enter a return-to-sport program (usually by week 12). Pain and swelling should be minimal and easily controlled before initiation of this phase. ROM should be full. However, the patient may have a slight restriction of knee flexion, with discomfort at the end ROM. Unless the patient is being treated conservatively secondary to repair of a complex or avascular tear, they should be able to tolerate full weight bearing without pain or swelling. The patient should exhibit normal gait mechanics. Good control of the LE musculature should be evident before activity is progressed. The goals of the intermediate phase are to normalize strength, ROM, gait, and endurance, as well as progress the patient into functional activities. Muscle flexibility exercises are continued as needed during this phase. Quadriceps and iliopsoas stretching to improve knee flexion and hip extension can be initiated. Strength exercises are continued and advanced as tolerated. Hamstring strengthening (with isotonic exercise) can be advanced during this phase. Progression is based on DeLorme’s principles.37 Resistance can be applied to the hamstring group gradually, based on patient tolerance.

Closed-chain activity can be advanced during this phase of rehabilitation. Progression of activity should be from simple linear movements to complex multidirectional movements. Patients are instructed to perform three sets of 10 to 30 repetitions as indicated. The patient must demonstrate adequate control of LE mechanics and not have adverse reactions (pain and swelling) from the simple linear movements before progressing to complex multidirectional movements. Variables of time, repetitions, ROM, and resistance are used in functionally progressing the rehabilitation program. Full weight-bearing heel raises, lateral step-ups, wall squats, minisquats with tubing, and partial lunges can be performed. ROM should be limited initially, with most activity being from 0° to 90°.

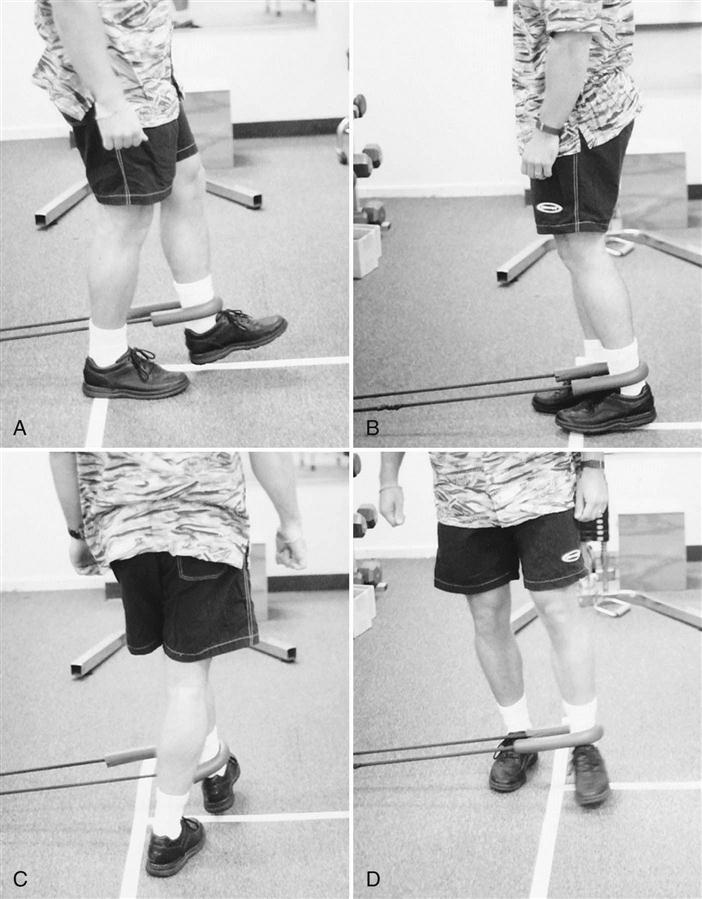

![]() Constant reassessment should occur, and patient tolerance to the particular activity must be demonstrated before any exercise progression. Balance and coordination exercises can be added to the rehabilitation program during the intermediate phase. Initial training is done bilaterally and progressed as tolerated to unilateral activities. Balance boards, trampolines, and elastic cords can be used. Single-limb balance and control can be performed with exercise tubing “T kicks” (Fig. 24-5). The uninvolved extremity has a cord attached distally; the involved extremity remains stationary with the knee in about 10° of flexion. The patient moves the uninvolved extremity into flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and diagonal planes. Initially the patient performs 10 to 15 repetitions for two sets in each plane of movement. The patient may require support for balance. The exercise can be progressed by altering the tubing resistance, increasing the repetition or time (up to 30 seconds in each plane), and altering the speed of movement (Fig. 24-6).

Constant reassessment should occur, and patient tolerance to the particular activity must be demonstrated before any exercise progression. Balance and coordination exercises can be added to the rehabilitation program during the intermediate phase. Initial training is done bilaterally and progressed as tolerated to unilateral activities. Balance boards, trampolines, and elastic cords can be used. Single-limb balance and control can be performed with exercise tubing “T kicks” (Fig. 24-5). The uninvolved extremity has a cord attached distally; the involved extremity remains stationary with the knee in about 10° of flexion. The patient moves the uninvolved extremity into flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, and diagonal planes. Initially the patient performs 10 to 15 repetitions for two sets in each plane of movement. The patient may require support for balance. The exercise can be progressed by altering the tubing resistance, increasing the repetition or time (up to 30 seconds in each plane), and altering the speed of movement (Fig. 24-6).

Cycling can be continued, with the patient modifying the workload parameters of speed, resistance, and duration based on response to the activity. Additional cardiovascular activity (e.g., stair-stepping machine, cross-country ski machine, treadmill) can be added based on patient response and tolerance.

A gradual walking-to-running program can be established toward the end of this phase based on weight-bearing tolerance and adequate closed-chain control and LE strength. (Refer to Chapter 34 for a detailed progressive running program.) Assessment of foot function with appropriate modifications may be helpful in minimizing abnormal joint and meniscus stress before initiating a running program. The running program can start with jogging in place on a trampoline and be progressed to treadmill running. Continued progression is based on patient tolerance and absence of pain and swelling.

Isokinetics strength and endurance training can be initiated during this phase. Tolerance to resisted quadriceps and hamstring strengthening must be demonstrated before an isokinetic program is initiated. A submaximal multispectrum program with a lower velocity speed of 180°/sec (three sets of 15 to 20 seconds) and higher velocity speed of 300°/sec (three sets up to 30 seconds) can be initiated. Progression is based on patient tolerance and adequate response to training.

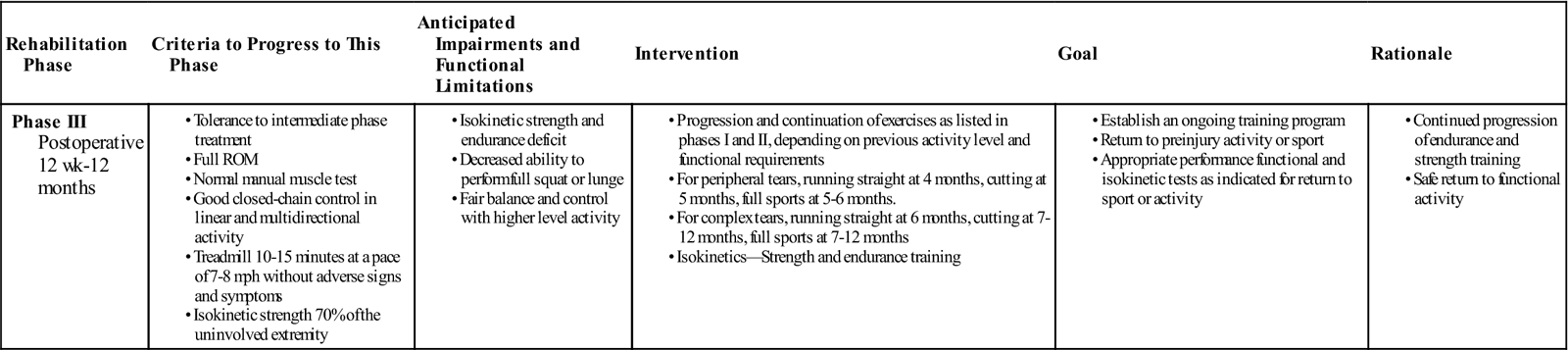

Phase III (Advanced Phase)

TIME: 12 to 18 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Return to sport or preinjury activities, establish an ongoing training program (Table 24-4)

TABLE 24-4

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase |

Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

| Phase III Postoperative 12 wk-12 months |

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Progression to the advanced phase of rehabilitation is based on tolerance to intermediate phase treatment. Typically this phase is initiated around 12 to 18 weeks. ROM should be complete without pain.

![]() Caution should be exhibited with full squat or lunge activity. These activities should be avoided early in the advanced phase and gradually introduced with progressive loading toward the end of the phase. Normal strength in all major muscle groups should be exhibited. The patient should exhibit good closed-chain control in linear and multidirectional activity. The goals of this phase are to establish a training program and return to sports or preinjury activity levels.

Caution should be exhibited with full squat or lunge activity. These activities should be avoided early in the advanced phase and gradually introduced with progressive loading toward the end of the phase. Normal strength in all major muscle groups should be exhibited. The patient should exhibit good closed-chain control in linear and multidirectional activity. The goals of this phase are to establish a training program and return to sports or preinjury activity levels.

Progression of strength and endurance training continues. New loads and demands are placed on the LE through running, agility, and plyometric training. Depending on previous activity level and functional requirements, agility, sprinting, and track running can be initiated. An indicator of patient progress in these activities is the ability to jog on a treadmill 10 to 15 minutes at a pace of 7 to 8 mph without adverse signs and symptoms. As with other knee disorders, adequate isokinetic strength (70% of the uninvolved extremity) can be used as an indication for progression to a running, agility, and plyometric program. A deficit of 10% or less is a reliable indicator of return to sport or activity participation.23 An initial plyometric program may include squat jumps in water. It serves as an effective alternative to dry land jumps by keeping adequate intensity while limiting the loads placed through the joint.42 However, other functional tests need to be assessed to ensure safe return. Refer to Chapter 34 for a more complete return to running program.

Suggested Home Maintenance for the Postsurgical Patient

An exercise program has been outlined at the various phases. The physical therapist can use it in customizing a patient-specific program.

Conclusion

Meniscal repair is an effective technique for preserving certain types of tears. Long-term results are still unknown, but the current literature supports preservation of the meniscus whenever possible to avoid the late sequelae of meniscectomy: progressive degeneration of the articular cartilage, flattening of the articular surfaces, and subchondral bone sclerosis. Numerous techniques are available to achieve this goal and selection is primarily a matter of surgeon preference. A rehabilitation program must be individually tailored based on tear specifics (size, location, repair technique), scientific evidence, clinical signs and symptoms, and patient needs.

Clinical Case Review

1Jonathan is a 52-year-old man who underwent an inside-out repair of a medial meniscus posterior-horn tear. On his first postoperative visit, he complains of numbness on the inside of his calf extending down the medial side of his leg. What do you tell the patient?

The patient underwent an inside-out repair of a medial meniscus tear, so the surgeon likely made a posteromedial incision through which he or she gained access to tie the sutures. The saphenous neurovascular structures lie an average of 22.6 mm away from this incision43 and is at risk during this approach (the peroneal nerve is at risk during the posterolateral incision). The patient’s nerve injury is likely a neuropraxia (stretching of the nerve but still in continuity) and should return, but the therapist should direct these types of questions to the operating surgeon.

2Martha is a 47-year-old woman who had a partial lateral meniscectomy for a complex tear approximately 3 weeks ago. This is her second visit, and she is complaining of pain, moderate knee swelling, and limited knee AROM (30° to 70°). What is most concerning at this point and why?

The patient has a 30° extension lag, and this is very concerning. The inability to fully extend affects gait biomechanics and can lead to the development of permanent flexion contractures if not addressed early. The patient may benefit from more aggressive stretching exercises, as well as a dynamic extension brace. Knee swelling and pain can persist a few weeks after surgery and should be evaluated, but this patient should have obtained full extension within the first week or two after surgery. Also, the patient underwent a partial meniscectomy and not a meniscal repair, so it would be extremely unlikely that the patient has sustained a new meniscal tear this early after surgery.

3Marek is a 49-year-old golfer who had a lateral posterior horn meniscal repair 3 weeks ago. You find his hamstring musculature remains weak. What would be an appropriate strengthening exercise. At what point will you apply a prone hamstring curl and why?

Bridging with a gym ball requires hip extension while maintaining knee ROM from 0° to 30°. Therefore, both gluteal and hamstring musculature are active in the hip extension role, without any active knee flexion. Active knee flexion pulls the medial and lateral meniscus posterior. The lateral meniscus migrates 1 cm posterior, because the popliteus muscle pulls it during knee flexion. This activity places increased stress on the repaired and healing tissues.

4Silvia is 40 years old. Before tearing her meniscus, she had two episodes of anterior knee pain over the past 3 years. Silvia had a medial meniscal repair 5 weeks ago. She has been progressing nicely with exercises, and the exercises have been advanced. After treatment she reports pain in the anterior inferior patella region with most of the exercises. Silvia is concerned because she almost slipped and fell after her last physical therapy visit. She denies any episode of her knee locking or becoming stuck. What might be the source of her pain?

Silvia’s history, along with the pain distribution pattern, indicates a patellofemoral joint problem that may have become irritated. Meniscal pain often produces complaints of pain near the joint line. Of course, a detailed assessment should be made and the physician notified. In this case the patellofemoral joint was the source of the anterior inferior knee pain. Therefore the patient should be treated for both the patellofemoral symptoms and the meniscal repair. Necessary restrictions should be maintained for each condition. After the patellofemoral symptoms have been significantly reduced or eliminated, the exercise program for the meniscal repair can again be the focus, with consideration of the patellofemoral joint.

5Darby is a 19-year-old female soccer player who had medial meniscal repair and ACL reconstruction of her right knee. She is 6 weeks postoperation but has noted progressive episodes of clicking in her knee with sit-to-stand transitions. Her swelling has increased, and she has had increased difficulty with walking and standing. What course of action should be taken?

She was reinstructed in an edema management program (i.e., elevation, compression, ice). Her therapeutic exercises and home exercise program were reevaluated for any provocative weight-bearing activities. The physician was called and an MRI was ordered (which revealed that the repair had torn). Complex tears have a higher incidence of failures than simple tears.

6Angie had a complicated radial repair of her right medial meniscus 7 weeks ago. You want to initiate weight-bearing frontal plane exercises without stressing the repair site. Prescribe three exercises with rationale.

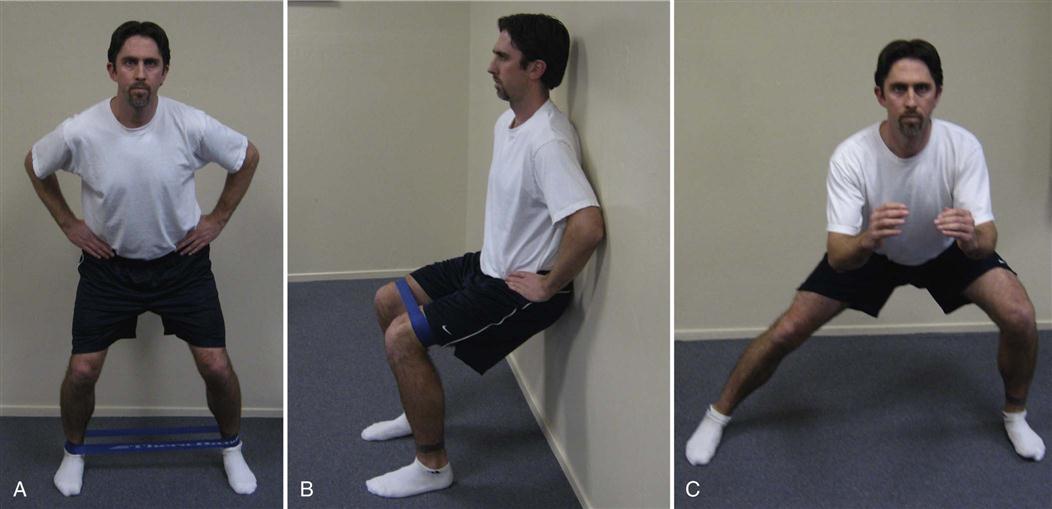

Side steps with resistance band to her right only, so no valgus force is placed through her medial collateral ligament and medial meniscus. Frontal plane lunges with glut dominant movement pattern, placing the knee at no more than 90° flexion. Wall squats with a resistance band around the distal thigh. This requires an isometric hip abduction contraction, strengthening the patient in the frontal plane.

7John is a 44-year-old recreational tennis player who underwent repair of his medial meniscus 8 weeks ago. He has progressed rapidly through his exercise program without any significant obstacles. He notes a sudden onset of swelling in his knee, which he relates to performing yard work (i.e., raking leaves, squatting down). Although his knee is swollen, no crepitation or locking is seen. His mild pain symptoms appear localized to the medial joint line. What changes should be made in his program?

It appears that he aggravated his repair site with squatting and pivoting activities. This activity should be avoided until he can clinically demonstrate tolerance to this stress. Use of minisquats or an inclined sled allows for the careful control of how much compression is delivered to the knee. Pivoting should be avoided for 6 months. John was cautioned about the risk of retearing his meniscus and his swelling was managed with relative rest, ES, ice, and elevation.

8Tammy is an active 45-year-old female who had a medial meniscal repair for a radial tear of the posterior horn 2 months ago. She has active knee ROM of 0° to 120° and is currently beginning closed-chain exercises to increase quadriceps and hamstring strength. She asks you if she can return to her Pilates class, which requires deep flexion squats without weight. What should the therapist tell her?

There are many reasons why Tammy should not return to Pilates at this time. First, she has not yet completed the closed-chain portion of her strengthening regimen, which includes toe raises, wall sits, and minisquats. After sufficient strength has been obtained, she must then progress to open-chain knee extension and flexion exercises and ultimately to balance/proprioceptive training before any type of strenuous activity can be initiated. Second, she underwent repair of a radial tear, and this type of tear should be treated more conservatively as it is more difficult to heal than longitudinal or peripheral tears. Third, the load-sharing percentage of the meniscus increases from 50% in full extension to 90% in 90° of flexion, with most of the force transmitted to the posterior horns of the menisci. This patient should refrain from forceful deep knee flexion activities for a period of 4 to 6 months.

9Tim is 3 months out of medial meniscal repair. He is progressing well except for the medial pain he feels as he approaches 90° of knee flexion while doing wall squats. Your movement analysis reveals excessive femoral adduction and internal rotation during the wall squat. What is your strategy to correct this?

Tim’s faulty movement pattern is most likely stressing his repair. The femoral adduction and internal rotation is a result of weak gluteal musculature, both hip abductors and external rotators. Therefore exercises based on recruitment of these muscles is optimal for correcting the alignment. These exercises would progress to weight-bearing exercises with resistance. For example, squats with resistance tubing wrapped around the distal thigh promotes recruitment of hip abductors, and cues the patient to maintain proper form while squatting.