CHAPTER 60 Meningioma Metastasis

INTRODUCTION

Metastasis is a process by which cancer spreads from its primary site to a distant location in the body.1 In ancient Greek the word metastasis means “translocation from one place to another” [Greek: meta, “to change” and histanai, “place”]. Such spread in the body is rarely encountered in meningiomas and the determinants of this rare phenomenon are still unknown almost a century after the first reported case.2–5

HISTORY

In 1926, Towne6 described the first case, in which the parasagittal meningioma in a 54-year-old man invaded the superior longitudinal sinus and other dural sinuses. The tumor spread by direct continuity to the superior vena cava via the left internal jugular vein. Since then approximately 100 case reports and small case series have been published, and these have established metastasis as a rare but significant process in both malignant and benign meningiomas.2–5

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Extraneural metastases are uncommon in central nervous system (CNS) tumors. In their analysis of Annual of the Pathological Autopsy Cases in Japan, Nakamura and colleagues7 concluded that the frequency of extracranial metastasis was 3.8% when of all brain tumors were considered. In this study extracranial metastases were most commonly found in primitive neuroectodermal tumors (PNET), meningioma, glioblastoma multiforme, and ependymoma.7 Another study conducted on 1011 children who were operated for intracranial tumors found an incidence of 0.98% with medulloblastoma, germ cell tumors, ependymoma, and atypical teratoid rhabdoid tumor (ATRT) with decreasing order of frequency.8 The relatively high incidence of metastasis in meningiomas when compared to other CNS tumors is not completely unexpected, as meningiomas arise outside the anatomic boundaries of the blood–brain barrier.3

The incidence of meningiomas in the general population has been estimated to be 2.3 per 100,000.9 They constitute 13% to 26% of all primary CNS tumors.9 Metastasis is rarely observed in meningiomas. There are only few small case series and few sporadic case reports totaling to around a hundred cases in the literature (Table 60-1). Hemangiopericytomas are excluded from this analysis.10 The incidence of metastasis is estimated to be 0.15% to 1% of all CNS meningiomas.2 Adlaka and colleagues5 analyzed 1992 primary intracranial meningiomas seen at the Mayo Clinic from 1972 through 1994 and identified three patients (0.15%) with documented extracranial metastasis. Enam and colleagues,3 in their analysis of 396 patients who initially presented with intracranial meningiomas, found the incidence for metastasis to be 0.76% when all meningiomas were considered and 42.8% when malignant (anaplastic) meningiomas were considered. No metastasis was observed in benign meningiomas in this cohort, which contained 5.8% atypical and 1.8% malignant meningiomas. Perry and colleagues, in their analysis of 116 malignant meningiomas, found that 3 (11%) of 27 frankly anaplastic meningiomas had metastasized. In this series metastasis accounted for the first malignant diagnosis in 2 (1.7%) of 116 cases and one of these cases had otherwise benign histology. Prayson4 reported an 26% incidence of metastasis in 23 patients with malignant meningiomas. All these reports support an increasing incidence of metastasis with increasing grade.

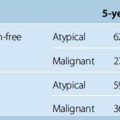

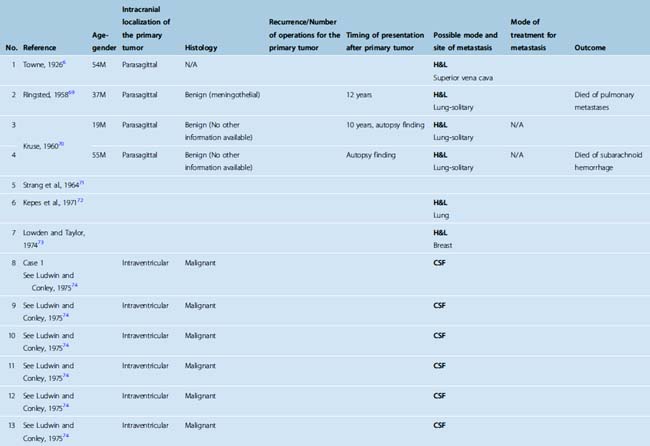

TABLE 60-1 Metastatic meningiomas (malignant cases appear in black, benign cases in blue, and unknown in green)

Metastatic meningiomas are more commonly seen in men (61.4%; see Table 60-1). This is in contrast with the overall female preponderance in primary disease.11 Most meningiomas occur in the middle and old age group, and metastatic cases are not an exception.10 The median age of the patients in literature was 47.5 (age range 6 months–87 years; see Table 60-1).

PATHOGENESIS–PATHOLOGY

Four mechanisms have been suggested for the occurrence meningioma at an extracranial site: (1) primary intracranial meningiomas with extracranial invasion, (2) distant metastasis from an intracranial lesion, (3) origin from arachnoid cells within cranial nerve sheaths (and from tumors outside the CNS), and (4) origin from embryonic rests of arachnoid cells (in peripheral organs that form de novo meningiomas).12 Distant metastasis from an intracranial meningioma can occur through hematogenous/lymphatic metastasis, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) seeding, or iatrogenic implantation. Information on the route of metastasis was available for 91 cases in our literature analysis. The most common routes for extracranial metastasis are hematogenous and lymphatic and these were identified in 65.9% of the cases. CSF seeding was seen in 29.7% and surgical implantation in 11% of these metastasis cases (see Table 60-1).

Hematogenous or Lymphatic Extracranial Metastasis

In our literature review we found lung metastases in 45.8%, bone metastases (including spine) in 24.1%, vertebral metastases in 19.3%, intracranial metastases in 16.9%, spinal intradural metastases in 12.1%, surgical site metastases in 12.1%, pleural metastases in 10.8%, lymph node metastases in 10.8%, intra-abdominal metastases in 9.6%, and at other sites (orbit, paranasal sinuses, thymus, parotid gland, heart and peripheral nerves) in 10.8% of the patients. Previous reports indicated that lungs and the pleura are the most common sites (60%), followed by liver and other abdominal viscera (34%), lymph nodes (especially cervical and mediastinal), vertebrae (11%), and other bones.3,11,13,14 Metastatic lesions in kidneys, urinary bladder, thyroid, breast, thymus, heart, skin, vulva, adrenal gland, and ocular fundus are reported but rarely encountered.15–17 Only 13% of the cases are reported to bear more than three metastases.18

There are 38 cases of meningioma metastases to the lung (see Table 60-1). Information on histology was present in 30 of these cases: 73.3% of these were benign, and 26.7% were malignant meningiomas; 3.3% of these had presented with a benign intracranial meningioma but had a malignant meningioma diagnosis in the metastasis. Information on the number of metastases was available in 22 cases, half of whom had solitary and half multiple metastases. Pleural metastases occur less frequently than lung metastases.18–25 In our analysis we identified pleural metastases in 23.7% of cases who had lung metastases. It should be kept in mind that meningiomas can be seen as primary tumors in the lung. This entity is exceedingly rare, and only 11 cases have been reported so far.5 Primary pulmonary meningiomas may be benign or malignant, solitary or multiple.26,27

It has been hypothesized that in meningiomas invading dural venous sinuses or cerebral veins, tumor cells may enter the systemic circulation.17,28 Drummond and colleagues11 stated that metastasis is more commonly observed in parasagittal and falcine meningiomas but the incidence must be very low considering the high percentage of meningiomas with venous sinus involvement that do not metastasize. In his well known study, Simpson29 observed infiltration of the dural sinuses in 34 (14%) of 246 intracranial meningiomas but extracranial metastatic lesions were detected in only one. After such systemic dissemination, tumor cells may enter the pulmonary circulation or the vertebral venous plexus. Rarely long bone metastases is seen in meningiomas, which suggests that metastasis through an arterial route may also be possible.30–32

Metastasis is commonly observed in malignant meningiomas and the rare metastases of histologically benign meningiomas typically occur after surgery. Several authors therefore have noted that surgery may predispose to systemic metastasis by allowing tumor cells to access the bloodstream and lymphatic circulation.3,33,34 This is supported by the fact that most metastases have been reported in patients who have undergone multiple operations for the cranial tumor recurrences. Russel and Rubinstein34 indicated that 70% of metastases are found in patients who have undergone at least one craniotomy. A notable finding was that 75% of these operated cases had invasion of a venous sinus.28 However, in few cases metastases were not associated with previous surgery.35,36

CSF Seeding

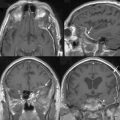

Although meningiomas are thought to arise from arachnoid cap cells and are naturally exposed to CSF, seeding through the CSF is even more rare than hematogenous spread.17,37–39 We identified 27 cases of meningiomas with metastatic spread through the CSF (see Table 60-1). Of these cases, 57.7% were malignant, 3.95% atypical, and 38.5% benign. In two cases (7.9%) the primary tumor was of benign histopathology but the metastatic lesion was diagnosed as a malignant meningioma. In most of the cases the primary tumor was an intraventricular meningioma (88.2% of the cases with known location of the primary). There was a very slight female predominance (43.8% men and 56.2% women). Chamberlain and Glantz40 reported the largest series of eight patients with CSF seeding confirmed by cytology, which interestingly included extraneural metastases in five (62.5%) cases. This particular cohort consisted of eight benign meningiomas that have received extensive treatment including multiple surgeries in all patients (median, two surgeries; range, one to five surgeries), external beam fractionated radiotherapy in seven (87.5%) patients (median dose, 54 grays [Gy]), stereotactic radiotherapy in five (62.5%) patients (median dose, 18 Gy), and chemotherapy in all patients (hydroxyurea administered for 3–9 months [median, 6 months]). As demonstrated in this small cohort and other case reports, the diagnosis of CSF spread can be supported by cytology.40,41 Otherwise, seeding through the CSF may be difficult to distinguish from multifocality, which should be suspected especially in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2).

Local Iatrogenic Seeding

Iatrogenic seeding, a.k.a. “implantation metastasis,” is thought to be caused by unintended implantation of tumor cells during surgery.42 The significance of iatrogenic seeding during surgery is not known because it is very rarely observed. As indicated in the preceding text, surgical manipulation may be a source of tumor spread and this may also be true for iatrogenic seeding. Most surgeons have experienced meningioma recurrence at the bone or subcutaneous tissue at the surgical flap, especially in patients with repeated craniotomies. We came across only 10 cases iatrogenic spread of meningiomas.5,21,32,39,40,42–46 In eight of these cases the metastases were in the head,5,21,32,39,40,42,43,45 in one case at the abdominal incision,43 and one case occurred in the temporalis muscle.46 In one patient recurrence was seen at the abdominal donor site of an autologous fat graft, which was placed into the orbit in a case of malignant sphenoid wing meningioma.43

Determinants or the mechanism of such a surgical spread is not known. One intriguing hypothesis is the local action of growth factors known to be induced during wound healing, such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and transforming growth factors (TGFs) may potentiate seeded tumor growth, and cause preferential tumor growth at this location but there are no clinical or experimental data to support this notion.47–50

Pathologic Correlates of Metastasis

Invasion and metastasis are generally considered to be the hallmarks of malignant behavior, and this is also true for meningiomas. In Cushing and Eisenhardt’s 1938 monograph, brain invasion was considered a sign of malignancy.51 Since then, extracranial metastasis had been referred as the strongest evidence of malignancy in meningiomas.3,34 However, accumulating evidence has indicated that this is not necessarily true. As noted in the preceding section on incidence, the risk of metastasis rises with increasing histologic grade. But when metastatic cases were analyzed it became apparent that some of these tumors had a benign histopathology and relatively better prognoses. In their analysis of 116 malignant meningiomas, Perry and colleagues37 concluded that the underlying histology was of greater prognostic significance than the fact that the tumor has metastasized. In current histopathologic classifications brain invasion alone does not sufficient for diagnosis of malignant meningioma and metastasis is considered an indicator of malignancy, but in meningiomas of any subtype.10 This is supported by cytogenetic findings indicating that metastasizing meningiomas do not necessarily have more complex genetic changes when compared to their non metastasizing counterparts.52 The histopathologic diagnosis, however, does not fully predict the biological behavior or the clinical outcome. Meningiomas that present with brain invasion have a prognosis comparable to atypical meningiomas.10 This also holds true for benign metastasizing meningiomas that fare far worse than ordinary cases.

The majority of meningiomas are benign. Malignant meningiomas constitute 1% to 2.8% of the cases.10,53 Metastasis is seen in 11% to 43% of the malignant tumors.3,37 Although less frequently seen, metastasis is also seen in intracranial meningiomas with benign histopathology. This led to the concept of “benign metastatic meningiomas.”16 We found a total of 35 histologically verified benign metastatic meningioma cases in the literature (see Table 60-1). Considering that benign meningiomas are 36 to 100 times more common than malignant meningiomas and the fact that there are comparable numbers of reports of metastasis in both benign and malignant meningiomas (malignant: benign ratio = 1.11) one can conclude that clinical presentation of metastasis is 40 to 110 times more common in malignant meningiomas. When we analyzed benign metastasizing meningiomas, we observed a male predominance, which was also the case in metastatic meningiomas in general. There was a clear predominance of parasagittal localization (72.2% of patients where the site of primary is reported).

Another possibility is that these new foci are not metastases but in fact previously undetected multifocal meningiomas. The findings of Strangl and colleagues54 who demonstrated monoclonality in half of the non-NF2–associated patients with multifocal meningiomas further supports this possibility. Whether these secondary growths in cases of benign meningiomas represent true metastases or de novo growth from ectopic embryologic remnants has yet to be proven.3 If these are in fact “real” metastases, another clinical implication would be that the benign histopathologic diagnosis in a meningioma (with the current histopathologic classification scheme) falls short of excluding metastasis.

Molecular Mechanisms of Invasion and Metastasis in Meningiomas

The mechanisms underlying invasion and metastasis are complex processes and the genetic and biochemical determinants remain incompletely understood.1 Basic research has indicated that the invasion–metastasis cascade in cancer encompasses local invasiveness, intravasation into and transport through the circulation, extravasation, formation of a micrometastasis, and finally, formation of a macroscopic metastasis.1 Meningiomas have a high propensity of invading surrounding structures. Some meningiomas tend to invade surrounding bone and induce hyperostosis. This may be present in histologically benign tumors and the underlying mechanisms are still unknown. Tumoral invasion is detected in all cases of hyperostosis.55 Meningiomas of all grades may also invade the surrounding brain parenchyma. Local invasion and metastasis are mediated by the interaction of tumor cells with the extracellular matrix. Modulation of the extracellular matrix by proteins associated with the tumor may be responsible for this invasion, as seen in the example with tenascin and peritumoral brain edema.56 The malignant histopathologic features of the meningioma may only reveal early tumor regrowth. Recently the role of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors, other proteases such as urokinase and tissue-type plasminogen activator and their inhibitors have been shown to be important in tumor metastasis and invasion.11,57–59

High proliferative potential has been suggested to predispose to metastasis.11 High MIB-1 or bromodeoxyuridine (BRDU) labeling indices have been related to atypical and malignant histology; however, the relationship to metastasis is unclear.

Gladin and colleagues60 studied loss of heterozygosity in their three patients with metastatic meningiomas. They reported that loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at 1p, 14q, and 9p was associated with increased aggressiveness and related metastasis. However, the genetic changes that characterize higher grade meningiomas have not been found in brain invasive, histologically benign meningiomas, indicating that invasion and malignant degeneration may be independent processes.10

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The clinical presentation of a metastatic meningioma is dictated by the anatomic localization of the metastatic tumor mass. Metastases within or around the neuraxis may present with headaches and/or neurological compression syndromes. One patient presented with a lateral medullary syndrome.61 Spinal intradural or epidural tumors may present with demonstrate spinal cord compression syndrome or pain.14,38

Incisional metastases are commonly detected at inspection and present as a mass at the surgical site, skin erosion or pain.32,39,42 Extraneural metastases present with signs and symptoms related to the site of metastasis. Pulmonary or pleural metastasis may reveal chest pain, hemoptysis, and difficulty in breathing.3,11,62

As noted in the preceding text, there have been several reports of CSF dissemination in intraventricular meningiomas.39 The role of craniospinal imaging can be performed in these cases. The predictive value and the yield of CSF cytology is not known.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the standard for diagnosing CNS cases. This is also true for vertebral metastases; however, CT may provide additional information on bone destruction.14

Plain radiography of the chest may demonstrate mass lesions, mediastinal shift, or pleural effusion.3 CT of the thorax may identify the mass lesions, pleural effusion, nodular thickening of pleura, or atelectasis of the lung.11,62 In lung lesions, the diagnosis can be established either by surgical resection or by needle aspiration biopsy.19,63 In patients with pleural effusion, thoracentesis may show exudative fluid accumulation. Cytologic evaluation may demonstrate tumor cells.19,21,25,63 The sensitivity of cytology in the pleural effusion seems to be low as five (50%) of the ten cases with pleural metastases reported negative results.18,20 Differential diagnosis of malignant meningioma cells in pleural effusion includes carcinoma, malignant mesothelioma, and sarcoma. Transthoracic tru-cut biopsy can be done for diagnosis.21 Most commonly, the histopathologic features are similar to those of the intracranial tumor, however anaplastic meningiomas have also been reported in patients with a prior diagnosis of a benign intracranial meningioma.21

TREATMENT

When we analyzed all reported cases for the mode of treatment we found out that 73.7% were operated, 41.6% had received radiotherapy, 33.3% had received chemotherapy, and 8.3% had received Gamma Knife® radiosurgery. Surgical resection is the mainstay of treatment in metastatic meningiomas when the lesions are not too numerable and if they are accessible. This also holds true for tumors in the calvarium, scalp, or in the spinal canal. Spinal metastases are also resected and aggressive surgery is performed in appropriate cases. Delgado and colleagues14 reported a patient with XIth dorsal vertebral body metastasis where they performed a total en bloc spondylectomy (Tomita’s procedure). Others questioned the need for aggressive surgical removal in spinal metastases, citing that results of surgical removal were not satisfactory and indicated that radiotherapy was an effective form of palliative treatment.64 Surgery is also indicated in extraneural metastases. Lung and pleura are the most common sites of metastasis outside the central nervous system and such lesions are managed by surgical resection.62,65 Resection of solitary as well as multiple metastases in both lungs have been reported using staged toracotomies.62,65 However, if the tumor is widely disseminated, radiotherapy is recommended.21

If metastases are too numerable, cannot be resected totally, or if the surgery is contraindicated fractionated radiotherapy can be used.21 It is not known whether immediate postoperative radiotherapy may reduce the risk of tumor seeding or metastasis.

Chemotherapy is of very limited value in meningiomas and most commonly used for salvage treatment. Aside from hydroxyurea, there are no other chemotherapeutic agents of significant therapeutic value and even this agent is seldom effective in atypical meningiomas.66 Therapeutic expectancy is also poor, with progression-free survival over 6 months considered as a meaningful response.40 None of the patients with spinal seeding metastasis responded to a combination of maximal surgery, maximal radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.40,67,68 Cramer68 reported a 4-month survival in their spinal metastatic patient, who started receiving hydroxyurea 14 months after diagnosis of spinal metastases. Chamberlain and Glantz40 reported their results in eight patients with CSF seeding treated aggressively with surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. The best response obtained with chemotherapy was stable disease in 87.5%, with 3.5 months median duration of response and therapy related toxicity in all.

OUTCOME

The result of the treatment in these patients is directly related to the spread of the metastatic tumor. Small metastatic deposits can be treated successfully. Diffuse chest and pleural infiltration of the metastatic meningioma, even after radiotherapy, carries a poor prognosis. In our analysis, outcome information was available for 35 patients, and 71.34% of them died as a result of metastatic meningioma. Mean survival in these patients with a mortal outcome was 14 months (SD: ±14 months). Chamberlain and Glantz40 reported a median survival of 5.5 months in their cohort of eight benign meningiomas with CSF seeding despite aggressive treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

[1] Gupta P.B., Mani S., Yang J., et al. The Evolving Portrait of Cancer Metastasis. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology, 2005. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press;

[2] Shuangshoti S., Hongsaprabhas C., Netsky M.G. Metastasizing meningioma. Cancer. 1970;26:832-841.

[3] Enam S.A., Abdulrauf S., Mehta B., et al. Metastasis in meningioma. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1996;138:1172-1177. discussion 1177–8

[4] Prayson R.A. Malignant meningioma: a clinicopathologic study of 23 patients including MIB1 and p53 immunohistochemistry. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:719-726.

[5] Adlakha A., Rao K., Adlakha H., et al. Meningioma metastatic to the lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:1129-1133.

[6] Towne E.B. Invasion of the intracranial venous sinuses by meningioma (Dural endothelioma). Ann Surg. 1926;83:321-327.

[7] Nakamura K., Hawkin S., Aizawa M., et al. Extracranial metastases of brain tumors–a case report and survey of patients with extracranial metastasis sampled from a report on pathological autopsy cases in Japan. Gan No Rinsho. 1986;32:281-286.

[8] Varan A., Sarı N., Akalan N., et al. Extraneural metastasis in intracranial tumors in children: the experience of a single center. J Neuro-Oncol. 2006;79:187-190.

[9] Whittle I.R., Smith C., Navoo P., Collie D. Meningiomas. Lancet. 2004;363:1535-1543.

[10] Louis D.N., Scheithauer B.W., Budka H., et al. Meninigomas. In: Kleihues P., Cavenee W.K., editors. The WHO Classification of Tumors of the Nervous System. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002:176-184.

[11] Drummond K.J., Bittar R.G., Fearnside M.R. Metastatic atypical meningioma: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7:69-72.

[12] Hoye S.J., Hoar C.S., Murray J.E. Extracranial meningioma presenting as a tumor of the neck. Am J Surg. 1960;100:486-489.

[13] Karasick J.L., Mullan S.F. A survey of metastatic meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1974;40:206-212.

[14] Delgado-Lopez P.D., Martin-Velasco V., Castilla-Diez J.M., et al. Metastatic meningioma to the eleventh dorsal vertebral body: total en bloc spondylectomy. Case report and review of the literature. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2006;17:240-249.

[15] Kepes J.J. Cellular whorls in brain tumors other than meningiomas. Cancer. 1976;37:2232-2237.

[16] Som P.M., Sacher M., Strenger S.W., et al. Benign” metastasizing meningiomas. Am J Neuroradiol. 1987;8:127-130.

[17] Kepes J.J. Meningiomas. Biology, Pathology, and Differential Diagnosis. New York: Masson Publishing, 1982.

[18] Kaminski J.M., Movsas B., King E., et al. Metastatic meningioma to the lung with multiple pleural metastases. Am J Clin Oncol. 2001;24:579-582.

[19] Tao L.C. Pulmonary metastases from intracranial meningioma diagnosed by aspiration biopsy cytology. Acta Cytol. 1991;35:524-528.

[20] Allen I.V., McClure J., McCormick D., Gleadhill C.A. LDH isoenzyme pattern in a meningioma with pulmonary metastases. J Pathol. 1977;123:187-191.

[21] Erman T., Hanta I., Haciyakupoglu S., et al. Huge bilateral pulmonary and pleural metastasis from intracranial meningioma: a case report and review of the literature. J Neurooncol. 2005;74:179-181.

[22] Pramesh C.S., Saklani A.P., Pantvaidya G.H., et al. Benign metastasizing meningioma. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:86-88.

[23] Kros J.M., Cella F., Bakker S.L., et al. Papillary meningioma with pleural metastasis: case report and literature review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2000;102:200-202.

[24] Hishima T., Fukayama M., Funata N., et al. Intracranial meningioma masquerading as a primary pleuropulmonary tumor. Pathol Int. 1995;45:617-621.

[25] Safneck J.R., Halliday W.C., Quinonez G. Metastatic meningioma detected in pleural fluid. Diagn Cytopathol. 1998;18:453-457.

[26] van der Meij J.J., Boomars K.A., van den Bosch J.M., et al. Primary pulmonary malignant meningioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1523-1525.

[27] Picquet J., Valo I., Jousset Y., Enon B. Primary pulmonary meningioma first suspected of being a lung metastasis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;79:1407-1409.

[28] Figueroa B.E., Quint D.J., McKeever P.E., et al. Extracranial metastatic meningioma. BRJ. 1999;72:513-516.

[29] Simpson D. Recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1957;20:22-39.

[30] Fabi A., Nuzzo C., Vidiri A., et al. Bone and lung metastases from intracranial meningioma. Anticancer Res. 2006;26:3835-3837.

[31] Goldman C.K., Bharara S., Palmer C.A., et al. Brain edema in meningiomas is associated with increased vascular endothelial growth factor expression. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:1269-1277.

[32] Sabit I., Schaefer S.D., Couldwell W.T. Modified infratemporal fossa approach via lateral transantral maxillotomy: a microsurgical model. Surg Neurol. 2002;58:21-31. discussion 31

[33] Tominaga T., Koshu K., Narita N., Yoshimoto T. Metastatic meningioma to the second cervical vertebral body: a case report. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:538-539. discussion 539–40

[34] Russell D.S., Rubinstein L.J. Pathology of Tumours of the Nervous System, 5th ed. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins, 1989.

[35] Russell T., Moss T. Metastasizing meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1986;19:1028-1030.

[36] Miller D.C., Ojeman R.G., Proppe K.H., et al. Benign metastatic meningioma: case report. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:763-766.

[37] Perry A., Scheithauer B.W., Stafford S.L., et al. Malignancy” in meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer. 1999;85:2046-2056.

[38] Shintaku M., Hashimoto K., Okamoto S. Intraventricular meningioma with anaplastic transformation and metastasis via the cerebrospinal fluid. Neuropathology. 2007;27:448-452.

[39] Darwish B., Munro I., Boet R., et al. Intraventricular meningioma with drop metastases and subgaleal metastatic nodule. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:787-791.

[40] Chamberlain M.C., Glantz M.J. Cerebrospinal fluid-disseminated meningioma. Cancer. 2005;103:1427-1430.

[41] Vinchon M., Ruchoux M.M., Lejeune J.P., et al. Carcinomatous meningitis in a case of anaplastic meningioma. J Neurooncol. 1995;23:239-243.

[42] Yuksel M., Pamir N., Ozer F., et al. The principles of surgical management in dumbbell tumors. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1996;10:569-573.

[43] Sadahira Y., Sugihara K., Manabe T. Iatrogenic implantation of malignant meningioma to the abdominal wall. Virchows Arch. 2001;438:316-318.

[44] Akai T., Shiraga S., Iizuka H., et al. Recurrent meningioma with metastasis to the skin incision–case report. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2004;44:600-602.

[45] Ludemann W.O., Obler R., Tatagiba M., Samii M. Seeding of malignant meningioma along a surgical trajectory on the scalp. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:683-686.

[46] Singh S., Cherian R.S., George B., et al. Unusual extra-axial central nervous system involvement of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: magnetic resonance imaging. Australas Radiol. 2000;44:112-114.

[47] Baird A., Walicke P.A. Fibroblast growth factors. Br Med Bull. 1989;45:438-452.

[48] Chernoff E.A., Robertson S. Epidermal growth factor and the onset of epithelial epidermal wound healing. Tissue Cell. 1990;22:123-135.

[49] Roberts A.B., Flanders K.C., Kondaiah P., et al. Transforming growth factor beta: biochemistry and roles in embryogenesis, tissue repair and remodeling, and carcinogenesis. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1988;44:157-197.

[50] Sieweke M.H., Thompson N.L., Sporn M.B., et al. Mediation of wound-related Rous sarcoma virus tumorigenesis by TGF-beta. Science. 1990;248:1656-1660.

[51] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas: Their classification, regional behavior, life history and surgical end results. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1938.

[52] Cerda-Nicolas M., Lopez-Gines C., Perez-Bacete M., et al. Histologically benign metastatic meningioma: morphological and cytogenetic study. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:194-198.

[53] Salcman M. Malignant meningiomas. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningiomas. New York: Raven Press; 1995:50-74.

[54] Stangl A.P., Wellenreuther R., Lenartz D., et al. Clonality of multiple meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:853-858.

[55] Pieper D.R., Al-Mefty O., Hanada Y., Buechner D. Hyperostosis associated with meningioma of the cranial base: secondary changes or tumor invasion. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:742-746.

[56] Kilic T., Bayri Y., Ozduman K., et al. Tenascin in meningioma: expression is correlated with anaplasia, vascular endothelial growth factor expression, and peritumoral edema but not with tumor border shape. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:183-192. discussion 192–3

[57] Nakagawa T., Kubota T., Kabuto M., et al. Production of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 by human brain tumors. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:69-77.

[58] Tamaki M., McDonald W., Amberger V.R., et al. Implantation of C6 astrocytoma spheroid into collagen type I gels: invasive, proliferative, and enzymatic characterizations. J Neurosurg. 1997;87:602-609.

[59] Bindal A.K., Hammoud M., Shi W.M., et al. Prognostic significance of proteolytic enzymes in human brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1994;22:101-110.

[60] Gladin C.R., Salsano E., Menghi F., et al. Loss of heterozygosity studies in extracranial metastatic meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2007;85:81-85.

[61] Kleinschmidt-DeMasters B.K., Avakian J.J. Wallenberg syndrome caused by CSF metastasis from malignant intraventricular meningioma. Clin Neuropathol. 1985;4:214-219.

[62] Asioli S., Senetta R., Maldi E., et al. Benign” metastatic meningioma: clinico-pathological analysis of one case metastasising to the lung and overview on the concepts of either primitive or metastatic meningiomas of the lung. Virchows Arch. 2007;450:591-594.

[63] Jha R.C., Weisbrod G.L., Dardick I., et al. Intracranial meningioma with pulmonary metastases: diagnosis by percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy and electron microscopy. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1991;42:287-290.

[64] Lee T.T., Landy H.J. Spinal metastases of malignant intracranial meningioma. Surg Neurol. 1998;50:437-441.

[65] Murrah C.P., Ferguson E.R., Jennelle R.L., et al. Resection of multiple pulmonary metastases from a recurrent intracranial meningioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1823-1824.

[66] LaMasters D.L., Watanabe T.J., Chambers E.F., et al. Multiplanar metrizamide-enhanced CT imaging of the foramen magnum. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1982;3:485-494.

[67] Ramakrishnamurthy T.V., Murty A.V., Purohit A.K., Sundaram C. Benign meningioma metastasizing through CSF pathways: a case report and review of literature. Neurol India. 2002;50:326-329.

[68] Cramer P., Thomale U.W., Okuducu A.F., et al. An atypical spinal meningioma with CSF metastasis: fatal progression despite aggressive treatment. Case report. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:153-158.

[69] Ringsted J. Meningeal tumours with extracranial metastases. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1958;43:9-20.

[70] Kruse M.F.J. Meningeal tumors with extracranial metastasis. Neurology. 1960;10:197-201.

[71] Strang R.R., Tovi D., Nordenstam H. Meningioma with intracerebral, cerebellar and visceral metastases. J Neurosurg. 1964;21:1098-1102.

[72] Kepes J.J., MacGee E.E., Vergara G., Sil R.A. Case report. Malignant meningioma with extensive pulmonary metastases. J Kans Med Soc. 1971;72:312-316.

[73] Lowden R.G., Taylor H.B. Angioblastic meningioma with metastasis to the breast. Arch Pathol. 1974;98:373-375.

[74] Ludwin S.K., Conley F.K. Malignant meningioma metastasizing through the cerebrospinal pathways. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38:136-142.

[75] Kollmannsberger A., Kazner E., Prechtel K., Stochdorph O. Extracranial metastasis of meningeal tumors. Malignant meningioma with regional lymph node metastasis. Zentralbl Neurochir. 1975;36:27-36.

[76] Jedrzejewska-Iwanowska A., Dowgiallo M. Case of malignant meningioma with multiple metastases to the heart and other organs. Pol Tyg Lek. 1976;31:2141-2142.

[77] Repola D., Weatherbee L. Meningioma with sarcomatous change and hepatic metastasis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1976;100:667-669.

[78] Salvati C.A. Metastatic meningioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1981;83:169-172.

[79] Wende S., Bohl J., Schubert R., Schulz V. Lung metastasis of a meningioma. Neuroradiology. 1983;24:287-291.

[80] Ishikura A., Tsukada A., Aoyama K., Watanabe K. [Malignant meningioma with extracranial metastasis]. Gan No Rinsho. 1983;29:1767-1771.

[81] Aumann J.L., van den Bosch J.M., Elbers J.R., Wagenaar S.J. Metastatic meningioma of the lung. Thorax. 1986;41:487-488.

[82] Tognetti F., Donati R., Bollini C. Metastatic spread of benign intracranial meningioma. J Neurosurg Sci. 1987;31:23-27.

[83] Strenger S.W., Huang Y.P., Sachdev V.P. Malignant meningioma within the third ventricle: a case report. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:465-468.

[84] Stoller J.K., Kavuru M., Mehta A.C., et al. Intracranial meningioma metastatic to the lung. Cleve Clin J Med. 1987;54:521-527.

[85] Pirotte B., David P., Noterman J., Brotchi J. Lower clivus and foramen magnum anterolateral meningiomas: surgical strategy. Neurol Res. 1998;20:577-584.

[86] Slavin M.L. Metastatic malignant meningioma. J Clin Neuroophthalmol. 1989;9:55-59.

[87] Kamiya K., Inagawa T., Nagasako R. Malignant intraventricular meningioma with spinal metastasis through the cerebrospinal fluid. Surg Neurol. 1989;32:213-218.

[88] Ng T.H.K., Wong M.P., Chan K.W. Benign metastasizing meningioma. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1990;92:152-154.

[89] Leighton S.E., Rees G.L., McDonald B., Alun-Jones T. Metastatic meningioma in the neck. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:229-231.

[90] Celli P., Palma L., Domenicucci M., Scarpinati M. Histologically benign recurrent meningioma metastasizing to the parotid gland: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:1113-1116. discussion 1116

[91] Akimura T., Orita T., Hayashida O., et al. Malignant meningioma metastasizing through the cerebrospinal pathway. Acta Neurol Scand. 1992;85:368-371.

[92] Mackay B., Bruner J.M., Luna M.A., Guillamondegui O.M. Malignant meningioma of the scalp. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1994;18:235-240.

[93] Scavuzzo H., Del Cazo F.J., Otero E., et al. The pulmonary metastasis of a benign meningioma. Arch Bronconeumol. 1994;30:266-268.

[94] Sato M., Matsushima Y., Taguchi J., et al. A case of intracranial malignant meningioma with extraneural metastases. No Shinkei Geka. 1995;23:633-637.

[95] Peh W.C., Fan Y.W. Case report: intraventricular meningioma with cerebellopontine angle and drop metastases. Br J Radiol. 1995;68:428-430.

[96] Tworek J.A., Mikhail A.A., Blaivas M. Meningioma: local recurrence and pulmonary metastasis diagnosed by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytol. 1997;41:946-947.

[97] Nabeya Y., Okazaki Y., Watanabe Y., et al. Metastatic malignant meningioma of the liver with hypoglycemia: report of a case. Surg Today. 1998;28:953-958.

[98] Yoshida D., Sugisaki Y., Tamaki T., et al. Intracranial malignant meningioma with abdominal metastases associated with hypoglycemic shock: a case report. J Neurooncol. 2000;47:51-58.

[99] Kovoor J.M., Jayakumar P.N., Srikanth S.G., et al. Solitary pulmonary metastasis from intracranial meningiothelial meningioma. Australas Radiol. 2002;46:65-68.

[100] Knoop M., Sola S., Hebecker R., et al. Rare pulmonary manifestation of an intracranial meningothelial meningioma. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2004;129:1854-1857.

[101] Fulkerson D.H., Horner T.G., Hattab E.M. Histologically benign intraventricular meningioma with concurrent pulmonary metastasis: case report and review of the literature. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2008;110:416-419.