CHAPTER 1 Meningioma

History of the Tumor and Its Management

Meningioma/s has attracted the attention of surgeons, anatomists, pathologists, and physicians for many centuries. Given the tendency of these neoplasms to cause thickening of the overlying calvarium, meningiomas have left an unmistakable mark on human skulls dated as far back as prehistoric times.1–4 Most of this evidence has come from the well-preserved skulls of the Incas in the Peruvian Andes that show classic hyperostosis indicating the presence of an underlying meningioma (Fig. 1-1).

FIGURE 1-1 Prehistoric Peruvian skull, showing hyperostosis from an underlying meningioma.

(From al-Rodhan NR, Laws ER Jr. Meningiomas: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. Neurosurgery 1990:26(5):832–46; discussion 846–7.)

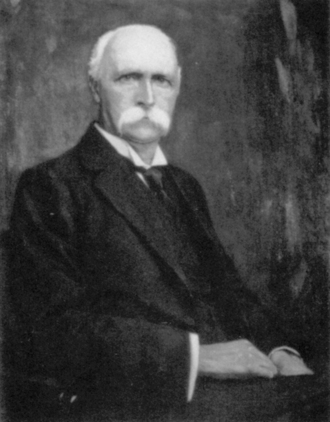

Felix Plater (Fig. 1–2) was probably the first to describe a meningioma in more recent times. Born in 1536 in Sion, Switzerland, he was educated at Montpellier, where he received his doctorate in 1557. Caspar Bonecurtius, a nobleman, was Plater’s patient with a meningioma who presented with gradual physical and mental deterioration. On autopsy, Plater described a round fleshy tumor, like an acorn.5,6 It was as large as a medium-sized apple, hard and full of holes. It was covered with a membrane and entwined with veins. Plater described it as having no connections with the matter of the brain, so much so that when it was removed by hand, it left behind a remarkable cavity. This first clear description of a meningioma is most consistent with an encapsulated meningioma.7,8 Felix Plater continued to practice as a distinguished Professor of Medicine at the University of Basel and died in Basel at the age of 78.

FIGURE 1-2 Felix Plater (1536–1614) of Switzerland, the first to describe a meningioma.

(From al-Rodhan NR, Laws ER Jr. Meningiomas: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. Neurosurgery 1990:26(5):832–46; discussion 846–7.)

NOMENCLATURE

Harvey Cushing coined the term meningioma in 1922 to describe a benign neoplasm of the meninges of the brain. However, many other surgeons and pathologists described and named this neoplasm as well. In fact, naming of the tumor likely represents one of the most frequently changed nomenclatures in the history of medicine. Antoine Louis, born in Metz, France, in 1723 into a family of surgeons, developed an interest in surgery of dural tumors, which he named tumeurs fongueuses de la dure-mere or fungoid tumors of the dura mater.9 He included their description in Memoire de l’Académie Royale de Chirurgie in 1774. In 1854, Sir James Paget named the neoplasm myeloid tumor (marrow like), based on its gross appearance and less malignant behavior. In 1863, Virchow was the first to describe the granules in these tumors and named it psammoma (sand-like). As Virchow was uncertain of the origin of these bodies, he gave the neoplasm a descriptive name. Subsequently, he changed the nomenclature from psammoma to Sarkoma der dura mater to describe these tumors.2,10

In the mid-1800s, Meyer, Bouchard, and Robin popularized the term epithelioma which was replaced later by the term endothelioma.2,10 Golgi believed that because the tumor was of mesenchymal origin, endothelioma was a more suitable term. Despite the myriad terminology, Virchow’s “sarcoma” and “psammoma” and Golgi’s “endothelioma” came into general use in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Harvey Cushing was troubled by the confusion that resulted from the different nomenclatures and thought that it would be desirable to place this tumor under a single unified designation. Cushing knew that since the cellular composition of the tumor was in dispute, a histogenic name would not be universally accepted. Further, because these tumors arose from many areas of the brain, a location-based tumor name was not possible. Therefore, Cushing decided on a simple, suitable “tissue name,” meningioma, that was “noncommittal and all-embracing.” In his Cavendish lecture in 1922, Harvey Cushing used this designation to discuss 85 patients with these tumors.10

CLASSIFICATION

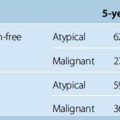

In 1863, Virchow was the first to attempt a classification of meningiomas.2 This was followed by classification schemas by Engert (1900), Cushing (1920), Oberling (1922), Globus (1935), Russell and Rubinstein (1971), and others.2,11 The World Health Organization (WHO) classification is widely used today and has been revised regularly.12 It includes the recent concept of the “atypical meningioma” as an aggressive variant. Table 1-1 lists the various classifications described.

| Year | Author | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | Engert | Four types: (1) fibromatous; (2) cellular; (3) sarcomatous; (4) angiomatous |

| 1920 | Cushing | Five types: (1) frontal; (2) paracentral; (3) parietal; (4) occipital; (5) temporal |

| 1922 | Oberling; later endorsed by Roussy | Three types: (1) type neuroepithelial; (2) type glial fusiforme; (3) type conjunctif |

| 1928 | Cushing and Bailey | Four types: (1) meningothelial; (2) fibroblastic; (3) angioblastic; (4) osteoblastic |

| 1930 | Bailey and Bucy | Nine types: (1) mesenchymatous; (2) angioblastic; (3) meningotheliomatous; (4) psammomatous; (5) osteoblastic; (6) fibroblastic; (7) melanoblastic; (8) lipomatous; (9) generalized sarcomatosis of the meninges. |

| 1935 | Globus | Five types: (with emphasis on the tumor content of pial vessels: (1) leptomeningioma; (2) pachymeningioma; (3) meningioma omniforme; (4) meningioma indifferentiale; (5) meningioma piale |

| 1938 | Cushing and Eisenhardt | Nine types with subvariants: (1) non-reticulin or collagen-forming meningothelial tumor; (2) meningothelial tumor pattern with tendency to form reticulin or collagen; (3) reticulin- or collagen-forming fibroblastic tumors of benign type; (4) reticulin-forming angioblastic tumors; (5) non–reticulin- or collagen forming epithelioid tumors; (6) reticulin- or collagen-forming fibroblastic tumors of malignant type; (7) osteoblastic meningiomas; (8) chondroblastic meningiomas; (9) lipoblastic |

| 1971 | Russell and Rubinstein | Five types: (1) syncytial; (2) transitional; (3) fibroblastic; (4) angioblastic; (5) mixed type |

| 2007 | WHO (World Health Organization) | (1) meningothelial: (2) fibrous (fibroblastic); (3) transitional (mixed); (4) psammomatous; (5) angiomatous; (6) microcystic; (7) secretory; (8) lymphoplasmacyte-rich; (9) metaplastic; (10) chordoid; (11) clear cell; (12) atypical; (13) papillary; (14) rhabdoid; (15) anaplastic (malignant) |

Adapted from Al-Rodhan and Laws2 (1990).

PATHOGENESIS

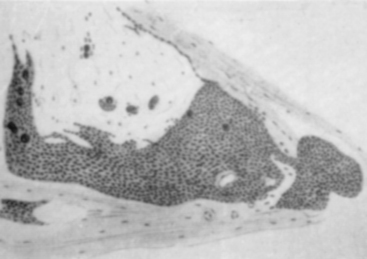

Antonius Pacchioni described arachnoidal granulations in 1705 as analogous to lymph glands.13 It was not until 1846, however, that Rainey suggested that these granulations were leptomeningeal in origin.14 Luschka, Ludwig Meyer, and Key and Retzius supported this view but the association between the granulations and meningeal tumors went unrecognized. In 1864, John Cleland, a Professor of Anatomy at Glasgow, described two dural tumors.15 One was an olfactory groove tumor and the other was right frontal in origin. In the dissecting suite, Cleland was able to separate the tumors from the dura, and hence appropriately described them as villous tumors of the arachnoid (Fig. 1-3). He suspected that they must have originated from the pacchionian corpuscles and attributed to them an arachnoidal origin. In 1902, Schmidt, after microscopic examinations of a series of meningeal tumors concluded that the cellular structure of these tumors was similar to the cell clusters capping the arachnoid villi16 (Fig. 1-4). Many other competing theories on the origin of these tumors were proposed by some of the leading physicians of the time, including Ribbert (connective tissue origin),17 Oberling (glial origin),18 and Roussy and Cornil (neuroepithelial origin).19 It was not until 1915, after Cushing and Weed confirmed that meningeal tumors arose from arachnoid cap cells, that Cleland’s theory gained widespread acceptance.20

ETIOLOGY

The association between head injury and meningioma development was first proposed by Berlinghieri in 1813.21 In 1888, Keen published a series of three surgical cases including a meningioma wherein he discussed the potential connection between head injury and meningioma. Cushing agreed with this connection and wrote2:

In 1986, Barnett and colleagues22 concluded that the association between meningioma and head trauma was largely anecdotal, but thought that trauma may contribute in the development of meningiomas in some cases. This association was later refuted by a systematic epidemiological analysis.22

Chronic irritation from abscess, hemorrhage, and tuberculosis were thought to have possible connection with the development of meningioma. Cushing and Eisenhardt, based on their experience in treating patients with von Recklinghausen’s disease, implicated congenital factors in the etiology of meningioma.2 In 1981, Deen and Laws presented evidence supporting the irritation theory by describing meningiomas that had developed contiguous to other primary brain tumors.23 Finally, cranial radiation has been shown to induce development of meningioma.24

RADIOGRAPHY

In 1897, Obici and Bollici were the first to image the cranium, followed by Oppenheim’s announcement in 1889 that imaging of the sella turcica was possible.2 In 1902, Mills and Pfahler were the first to provide a radiologic account of a meningioma.25

By 1920 may other reports of meningiomas were published and stereo-roentgenoscopy was in widespread use. The technology progressed through a series of improvements such as replacement of the old glass plates with more sensitive films, thus shortening exposure time.7 However, the largest improvement in the visualization of brain tumors (including meningiomas) came with Dandy’s seminal paper on the use of ventriculograpy in 1918.26 Later as the utility of ventriculograpy became more apparent, Cushing and Eisenhardt described it as “one of the most dependable contributions to tumor localization and diagnosis ever made.”2

SURGICAL RESECTION

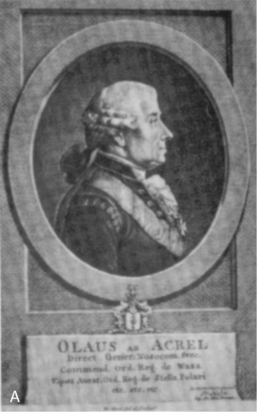

In 1743, Heister in Helmstead, Germany was the first to treat a meningioma surgically.2 His patient was a 34-year-old Peruvian soldier who developed a postoperative infection and died after Heister had applied a caustic lime to the tumor. At autopsy, Heister termed the tumor de tumore capitis fungoso. Olaf Acrel (Fig. 1-5A), the father of Swedish surgery, operated on a brain tumor in a 30-year-old patient with a history of head injury 18 months earlier2 (Fig. 1-5B). The patient was found to have a pulsatile tumor that was explored by insertion of a finger. Severe bleeding and convulsions ensued and the patient died a few days later.

In 1847, Zanobi Pecchioli of Italy performed the first successful meningioma removal.27 He was a professor of operative medicine and surgery at Siena University and published a series of 1524 operations, 16 of which were neurosurgical procedures. One of his cases involved a large meningioma of the right sinciput. He removed the tumor through a triangular flap made by drilling three widely spaced burr holes. The operative site was covered with sweet almond oil–soaked cambric. The patient survived for more than 30 months, and in 1840, the description of this operation was chosen for the competition for the chair of surgery at the University of Paris.

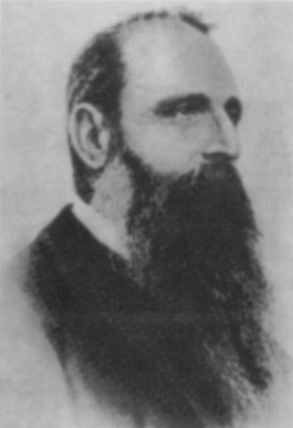

In 1879, Sir William McEwen carried out a successful meningioma removal in Glasgow, the first in northern Europe (Fig. 1-6). In the 19th century, the most celebrated and well known neurosurgical operation was performed by Franceso Durante (Fig. 1-7) of Italy on June 1, 1885.21,28 His patient was a 35-year-old woman with a left olfactory grove meningioma. Durante completely resected the lobular apple size tumor, which weighed 70 grams, in 1 hour. He left a drainage tube that came down to the left nasal fossa through the opening made in the ethmoid sinus by the tumor. On postoperative day 7 the tube was removed and the patient was discharged home. The patient did very well and required a reoperation 11 years later for a recurrence. As a result of the favorable outcome of the patient, this case was published in Lancet in 1887 and presented at the International Medical Congress in Washington, DC, in September of the same year.28

FIGURE 1-6 Sir William McEwen.

(From al-Rodhan NR, Laws ER Jr. Meningiomas: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. Neurosurgery 1990:26(5):832–46; discussion 846–7.)

FIGURE 1-7 Francesco Durante (1844–1934).

(From al-Rodhan NR, Laws ER Jr. Meningiomas: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. Neurosurgery 1990:26(5):832–46; discussion 846–7.)

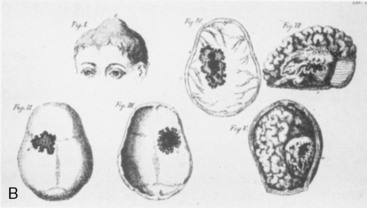

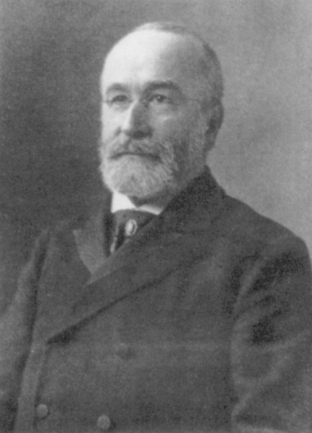

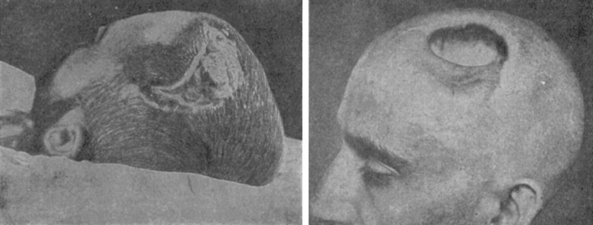

William W. Keen (Fig. 1-8), one of America’s pioneer neurosurgeons, was the first to successfully remove a meningioma in the United States on December 15, 1887. Keen was chair of surgery at the Jefferson Medical College in his home town of Philadelphia. His meningioma patient was a 26-year-old carriage maker with headaches, seizures, and partial blindness (Fig. 1-9). The patient reported a history of head injury as a child and Keen documented an aphasia and a right hemiparesis on physical examination. The operation was performed after intricate antiseptic measures such as removal of the carpet from the operating theater and cleaning of the walls and ceiling. The operation commenced at 1 P.M. to maximize natural light and lasted 2 hours. The tumor, weighing 88 grams, was completely removed via a frontotemporal craniotomy. Although the procedure was complicated by cerebrospinal fluid leakage and poor wound healing for 5 weeks, the patient recovered and was discharged on postoperative day 84. In gratitude, the patient promised Keen his brain for study. Keen, nearly 30 years older than the patient, outlived him. The patient died 30 years and 44 days after the operation, and the promise was kept on January 29, 1918.7,29

FIGURE 1-8 William W. Keen (1837–1932) of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

(From al-Rodhan NR, Laws ER Jr. Meningiomas: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. Neurosurgery 1990:26(5):832–46; discussion 846–7.)

FIGURE 1-9 Keen’s early case of a meningioma.

(From al-Rodhan NR, Laws ER Jr. Meningiomas: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. Neurosurgery 1990:26(5):832–46; discussion 846–7.)

Harvey Cushing’s contributions to the surgical resection of meningioma are unequaled. Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Harvey Cushing (Fig. 1-10) graduated Harvard Medical School in 1895 and joined Halsted’s surgical service at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. In 1912, he became Professor of Surgery at Harvard and Surgeon-in-Chief at the Peter Bent Brigham Hospital. Cushing’s most famous meningioma patient was General Leonard Wood, a military surgeon, Chief of Staff of the United States Army. In 1909, he presented to Cushing with frequent left-sided jacksonian attacks. The next year, Cushing, in a two-stage operation, 4 days apart, resected his right parasagittal meningioma. General Wood was discharged in good health and went on to be the Republican favorite to succeed President Woodrow Wilson. He re-consulted Cushing in 1927, complaining of severe left sided spasticity. Unfortunately, hours after this reoperation, Wood suffered an intraventricular hemorrhage and died.2

COMMENTARY

The improvement in neurosurgical outcomes at the turn of the 20th century was a result of more refined surgical technique, application of Lister’s antiseptic principles, and more precise localization of tumor.4,7 Cushing’s contributions were crucial to the advancement of intracranial surgery for meningioma and for that matter, all of neurosurgery in general. In 1922, Cushing concluded his Cavendish lecture by saying10:

MacCarty, considering the role of meningioma in neurosurgical history, thought that it had the most prominent role on the development of surgery of the central nervous system30:

[1] Abbott K.H., Courville C.B. Historical notes on the meningiomas. I. A study of hyperostosis in prehistoric skulls. Bull Los Angeles Neurol Soc. 1939;4:101-113.

[2] Cushing H., Eisenhardt L. Meningiomas: Their Classification, Regional Behaviour, Life History and Surgical End Results. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1938.

[3] Moodie R.L. Studies inR. XVIII. Tumors of the head among pre-Columbian Peruvians. Ann Med Hist. 1926;8:394-412.

[4] Wang H., Lanzino G., Laws E.R.J. Meningioma: the soul of neurosurgery: historical review. Sem Neurosurg. 2003;14:163-168.

[5] Netsky M.G. The first account of a meningioma. Bull Hist Med. 1956;30:465-468.

[6] Plater F. Observationum in hominis affectibus plerisque, corpori et animo, functionum laesione, dolore, aliave molestia et vitio incommodantibus, libri tres. Basileae: Impensis Ludovici Konig, 1614.

[7] Al-Rodhan N.R., Laws E.R.Jr. Meningioma: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. Neurosurgery. 1990;26:832-846. discussion 846–837

[8] Al-Rodhan N.R., Laws E.R.Jr. Meningioma: a historical study of the tumor and its surgical management. In: Al-Mefty O., editor. Meningioma. New York: Raven Press; 1991:1-8.

[9] Louis A. Mémoire sur les Tumeuers Fongueuses de la Dure-mère. Mem Acad R Chir Paris. 1774;5:1-59.

[10] Cushing H. The meningiomas (dural endotheliomas): their source, and favored seats of origin. Brain. 1922;45:282-316.

[11] Russell D.S., Rubenstein L.J. Pathology of Tumors of the Nervous System. London: Edward Arnold, 1971.

[12] Louis D.N., Ohgaki H., Wiestler O.D., Cavanee W.K. WHO Classification of Tumours of the Central Nervous System. Geneva: WHO Press, 2007.

[13] Pacchioni A. Dissertatio epistolaris de gladulis conglobatis durae meningis humanae, 1705. Rome

[14] Rainey G. On the ganglionic character of the arachnoid membrane of the brain and spinal marrow. Med Chir Trans. 1846;29:85-102.

[15] Cleland J. Description of two tumors adherent to the deep surface of the dura mater. Glasgow Med J. 1864;11:148-159.

[16] Schmidt M. Ueber die pachioniischen Granulationen u. ihr Verhaltniss zu den Sarcomen u. Psammomen der Dura Mater. Virchows Arch. 1902;170:429-469.

[17] Ribbert M.W. Uber das Endotheliom der Dura. Virchows Arch. 1910;200:141-151.

[18] Oberling C. Les tumeurs des meninges. Bull Assoc Franc Cancer. 1922;11:365-394.

[19] Learmonth J.R. On leptomeningiomas (edotheliomas) of the spinal cord. Br J Surg. 1927;14:396-476.

[20] Cushing H., Weed L.H. Studies on the cerebrospinal fluid and its pathway. IX. Calcarious and osseous deposits in the arachnoidea. Johns Hopkins Hosp Bull. 1915;26:367-372.

[21] Guidetti B., Giuffre R., Valente V. Italian contribution to the origin of neurosurgery. Surg Neurol. 1983;20:335-346.

[22] Barnett G.H., Chou S.M., Bay J.W. Posttraumatic intracranial meningioma: a case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:75-78.

[23] Deen H.G., Laws E.R. Multiple primary brain tumors of different cell types. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:20-25.

[24] Waga S., Handa H. Radiation-induced meningioma: with review of literature. Surg Neurol. 1976;5:215-219.

[25] Mills C.K., Pfaher G.E. Tumors of the brain localized clinically and by roentgen rays, with some observations relating to the use of the roentgen rays in the diagnosis of lesions of the brain. Phil Med J. 1902;9:268-273.

[26] Dandy W.E. Ventriculography following the injection of air into the cerebral ventricles. Ann Surg. 1918;68:5-11.

[27] Giuffre R. Successful radical removal of an intracranial meningioma in 1835 by Professor Pecchioli of Siena. J Neurosurg. 1984;60:47-51.

[28] Durante F. Contribution to endocranial surgery. Lancet. 1887;2:654-655.

[29] Keen W.W., Ellis A.G. Removal of a brain tumor, report of a case in which the patient survived for more than thirty years. JAMA. 1918;70:1905-1909.

[30] MacCarty C.S. The Surgical Treatment of Intracranial Meningiomas. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas, 1961.