Melolabial Flaps

Introduction

Because of the proximity of the melolabial fold to the nose and lips, melolabial flaps have long been used to repair these structures.1,2 During the 19th and 20th centuries, many varieties of melolabial flaps were described.3 In the past, such flaps have been called nasolabial flaps, but the term melolabial is more accurate in description as the prefix melo- refers to the cheek and the suffix -labial refers to the lips. Thus, it is more accurate to use the term melolabial crease rather than nasolabial crease because the crease separates the lips from the cheek, not the nose from the lip. This chapter discusses only cutaneous flaps harvested from the mound of skin immediately lateral to the melolabial crease and known as the melolabial fold.

Local cutaneous flap classification and terminology are discussed in detail in Chapter 6, but a brief summary here is helpful in understanding the mechanisms of movement of flaps harvested from the melolabial fold. Classification of flaps by method of transfer, which is to say by tissue movement, is usually the most convenient way of discussing flaps relative to their use in repair of facial cutaneous defects.4–6 It also contributes to the understanding of where standing cutaneous deformities develop and where the maximum wound closure tension occurs during wound repair. By use of this classification, melolabial flaps may be categorized as pivotal, advancement, and hinge. Melolabial hinge flaps are rarely used and are not discussed in this chapter. Advancement in the majority of situations depends on stretching the flap skin in the direction of flap movement. Such flaps are subjected to an increase in wound closure tension. In contrast, pivotal flaps rotate about a point at their base and in their purest form are not stretched. Thus, they are not subjected to wound closure tension greater than the natural tension of the remaining facial skin, although the repair of the donor site of the flap is subjected to increased tension. There are three types of pivotal flaps: rotation, transposition, and interpolated. Transposition and interpolated flaps may be transferred on a cutaneous pedicle or subcutaneous tissue pedicle. In the latter case, the flap is referred to as an island flap because it has no cutaneous connection to the donor site. Island transposition pivotal flaps are occasionally harvested from the melolabial fold but are uncommonly used and are not discussed. Rotation flaps are pivotal flaps with a curvilinear configuration. They must be designed immediately adjacent to the defect and are best used to close triangular defects. In the author’s practice, local flaps in the form of rotation are rarely designed in the area of the melolabial fold because their curvilinear incision frequently creates a scar that crosses the melolabial crease perpendicular to relaxed skin tension lines (RSTLs). For this reason, rotation flaps are not discussed.

Melolabial Transposition Flaps

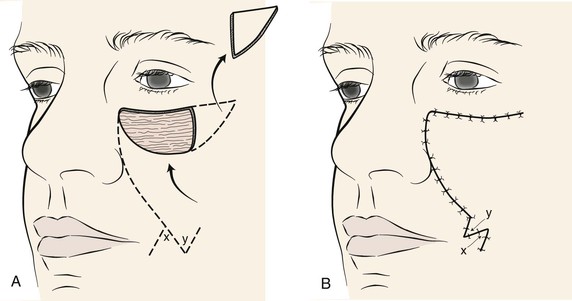

The majority of melolabial transposition flaps are designed as a rectangle, parabola, or rhombus. The axes of these flaps are usually oriented along or are parallel to the axis of the melolabial fold (Fig. 12-1). Closure of the flap donor site is within or parallel to the melolabial crease. The flap may be lengthy relative to its width, which facilitates closure of the donor defect without excessive wound closure tension. Melolabial transposition flaps used to repair small (2 cm or less) cutaneous defects of the medial cheek may be based superiorly or inferiorly. However, transposition flaps used to repair medial cheek defects larger than 3 cm should be based superiorly because there is more redundancy of facial skin in the inferior cheek, in the region of the jowl. In older patients, this redundancy can provide a source for a large flap and still enable primary closure of the donor site. Flaps should be designed so that whenever possible, closure of the donor site is in the melolabial and labial mandibular creases. When superiorly based melolabial transposition flaps are used, the standing cutaneous deformity is removed just medial or lateral to the superior border of the defect, depending on whether the flap is pivoted medially or laterally.

FIGURE 12-1 A, Skin defects of medial cheek can be repaired with melolabial transposition flaps. Broken line outlines incision for flap. B, Standing cutaneous deformities removed from base of flap and cheek donor site on flap transfer and closure of donor site.

Transposition flaps are pivotal flaps, and the greater the arc of pivotal movement, the greater will be the size of the standing cutaneous deformity and the less will be the effective length of the flap (see discussion in Chapter 8). The reduction in effective length must be accounted for in designing melolabial transposition flaps so that greater pivoting requires a longer design of the flap. To limit this restricting factor, whenever possible, melolabial transposition flaps should be designed to pivot no more than 90°.

Melolabial Advancement Flaps

Melolabial Unipedicle Advancement Flaps

Unipedicle advancement flaps are created by parallel incisions that allow a sliding movement of skin in a single vector toward the defect. This movement is in one direction, and the flap advances directly over the defect. As a consequence, the flap must be developed adjacent to the defect, and one border of the defect becomes the leading border of the flap. Melolabial advancement flaps are not frequently designed with two parallel incisions. When they are used to repair skin defects of the superomedial cheek, melolabial advancement flaps are usually designed by making only one long incision in the melolabial crease and undermining the skin of the fold lateral to the incision (Fig. 12-2). Skin is then advanced upward in a vector parallel to the melolabial crease with some additional slight pivotal movement. The pivotal movement, although limited, eliminates the need to make the second incision parallel to the first incision to create and to move the flap. A standing cutaneous deformity is excised lateral to the skin defect parallel to the inferior bony orbital rim.

Melolabial Island Advancement Flaps

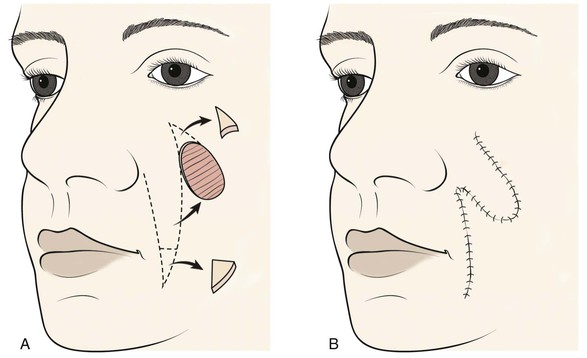

The melolabial V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap is an option for repair of medial cheek skin defects at or below the level of the nasal alae.7 The flap is particularly well suited for skin defects located immediately adjacent to the alae (Fig. 12-3). A triangle-shaped skin island is designed with the base of the triangle formed by the inferior margin of the defect. Optimally, the vector of flap advancement is designed parallel to the melolabial crease. The width of the skin island should equal the width of the defect at its widest point. The height of the skin island should generally be twice the height of the defect. The trailing half of the skin island tapers to a point to facilitate donor site closure in a V-Y fashion after flap advancement. The flap is therefore sometimes referred to as a V-Y island advancement flap. The skin island may extend as far as the inferior border of the mandible if necessary. Positioning the inferior tip of the skin island directly in the melolabial crease optimally conceals the donor site scar. Insofar as possible, incisions should be designed so that their scars are parallel to or in borders of aesthetic regions.

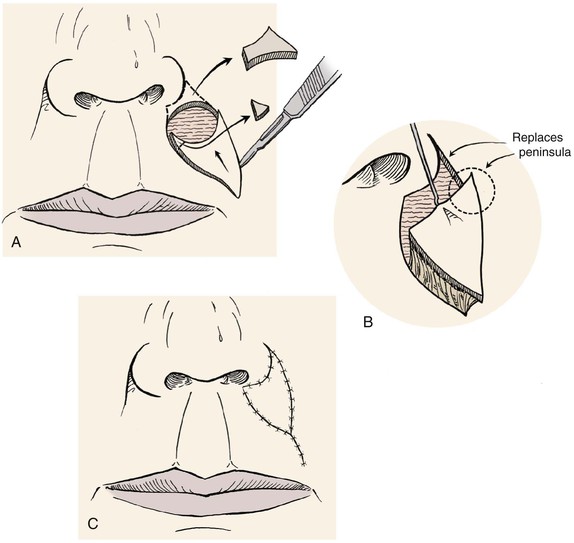

FIGURE 12-3 Melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flaps are particularly suited for repair of skin defects adjacent to alar base. A, Defect enlarged to remove peninsula of skin between ala and melolabial fold. Island flap designed to replace skin peninsula. B, Flap is based on subcutaneous fat of melolabial fold. C, Superior and lateral portions of wound closure suture lines are in aesthetic boundaries.

The perimeter of the skin island is incised to the level of the superficial subcutaneous fat. Undermining of the adjacent facial skin for a distance of 2 cm is performed at this level. Blunt and sharp dissection is then carried through the subcutaneous tissue surrounding the skin island, beveling slightly away from the skin island down to the level of the fascia overlying the facial muscles. This frees the elastic subcutaneous tissue pedicle from its medial and lateral fibrous attachments to the surrounding cheek fat while preserving its vascular supply, which is derived from its deep attachments. The skin island is then advanced toward the defect by placing a skin hook at its leading border. At this point, the pedicle can be narrowed to facilitate the advancement of the flap. This is accomplished by back cutting the peripheral borders of the flap in the subcutaneous tissue plane, leaving at least one-third of the total flap surface area attached to the underlying subcutaneous tissue. Further thinning of the subcutaneous tissue of the undermined leading border of the flap may be performed to create an appropriate thickness match between the border of the flap and the recipient site. A central pedicle attached to at least one-third of the total skin island surface area will adequately perfuse the flap. Further subcutaneous undermining of the skin adjacent to the flap is required if puckering of the peripheral facial skin occurs with flap mobilization (see Fig. 12-3). Subcutaneous undermining is also performed at the recipient site. In addition, the recipient site’s depth and shape may be modified by removing skin and subcutaneous tissue so that scars will be positioned along aesthetic boundary lines and the defect will more appropriately accommodate the thickness of the advancement flap. The leading border of the skin island is fixed in place, and the wound surrounding the remaining perimeter of the flap is subsequently closed such that wound closure tension is equally distributed over the entire length of the flap. The flap donor site is closed in a V-Y fashion, with care taken to compensate for any differences in the length of the opposing margins of the donor site by suturing on a bias (see Chapter 6).

For sizeable (2-3 cm) lip skin defects adjacent to the inferior border of the ala, it may be beneficial to excise the small peninsula of skin between the ala and melolabial fold in the process of enlarging the defect so that it extends to an aesthetic boundary.8 The peninsula is then reconstructed by appropriately designing the island flap so that the superior portion of the flap replaces the peninsula (see Fig. 12-3). This technique provides the best scar camouflage because the superior border of the flap is positioned within the aesthetic boundaries of the alar-facial sulcus and melolabial crease. When this peninsula is not replaced, the flap must cross the base of the peninsula and may mar an otherwise excellent result.

Melolabial Interpolated Subcutaneous Tissue Pedicle Flaps

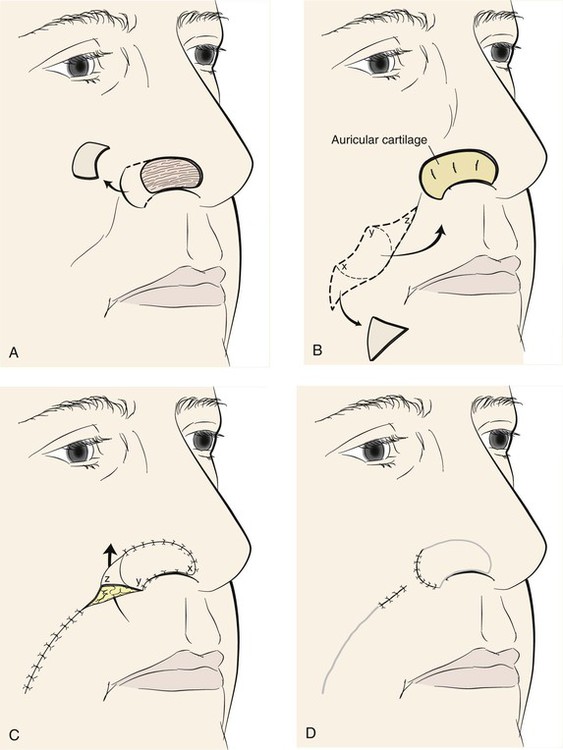

Melolabial transposition flaps have frequently been used for reconstruction of the ala and nasal sidewall. They have the advantage of maintaining a lymphatic drainage route through the pedicle of the flap, which remains in continuity with cheek skin. They also avoid a circumferential scar, which in part accounts for trap-door deformity. Why not use a transposition flap instead of an interpolated flap for ala repair? Both flaps have the advantage of using skin with color, texture, sebaceous glandularity, and thickness similar to those of the natural skin of the ala. Both flaps leave an acceptable donor scar in the depth of the melolabial crease. The main reason for not using a melolabial transposition flap is that it deforms the alar-facial sulcus and lateral portion of the alar groove. A portion of the flap by necessity must pass through the superior aspect of the alar-facial sulcus, which represents an important topographic junction between the facial aesthetic regions of the nose, cheek, and upper lip. Whenever possible, local flaps should be designed so that they do not cross borders that separate aesthetic regions. This is especially true if the border has a concave topography, like that of the alar-facial sulcus.9 Too often, this sulcus has been violated by transposition flaps harvested from the cheek to reconstruct lower lateral nasal defects. The flap passes through the sulcus, obliterating the valley between the ala and cheek. When this happens, it is extremely difficult to restore the valley to a completely natural contour. For this reason, an interpolated melolabial flap is recommended for reconstruction of the ala. The pedicle of the flap does not extend through the alar-facial sulcus, it crosses over the sulcus. The pedicle may consist of skin and subcutaneous fat or subcutaneous fat only and is detached from the cheek 3 weeks after the initial transfer to the nose. Although 3 weeks is a lengthy period for the patient to endure the deformity caused by the attachment of the flap’s pedicle to the cheek, this interval enables the surgeon to thin and sculpt the subcutaneous tissues of the distal flap at the time of flap transfer and the proximal portion of the flap at the time of pedicle detachment and flap inset. On inset of the flap, the patient is left with a completely natural alar-facial sulcus because no incision or dissection has been performed in this region. Because of this advantage, I recommend the choice of an interpolated design when a pivotal cheek flap is planned for reconstruction of a defect of the ala and the defect does not extend laterally to the alar-facial sulcus (Fig. 12-4).10

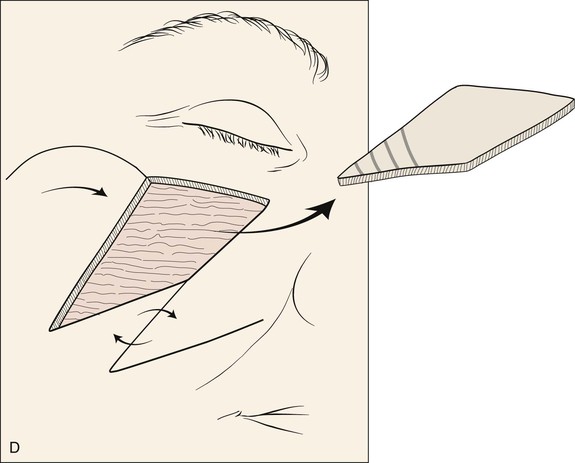

FIGURE 12-4 A, Skin defect of ala. Remaining skin of aesthetic unit removed. B, Auricular cartilage graft used for structural support of ala. Interpolated melolabial flap designed for covering of cartilage graft. Flap pivots toward midline. C, Subcutaneous tissue pedicle of flap crosses over alar-facial sulcus, necessitating subsequent division of pedicle. D, Second stage consists of division of pedicle and flap inset.

The nasal-alar unit is highly contoured, has a free margin, and functions as the external nasal valve. In reconstructing the ala, consistent results require a cartilage subsurface framework to resist the forces of scar contraction, to provide a stable external valve, and to serve as a scaffold for contour. The framework in the form of a cartilage graft must be used at the time of the initial reconstructive procedure and requires vascularized tissue superficial and deep to the graft, totally enveloping the cartilage. Adequate function of the nose requires a thin internal layer most appropriately supplied by vascularized mucosa.11 The external covering flap is provided by an interpolated cheek or forehead flap. Lining flaps and structural grafts for defects of the nose are discussed in detail in Chapter 18.

The porous and sebaceous nature of medial cheek skin closely resembles that of the caudal third of the nose, so an interpolated melolabial flap is generally the preferred covering flap for alar reconstruction. The flap is based superiorly on the rich vascular supply in the region of the alar-facial sulcus described by Herbert.12 At this location, perforating branches from the angular artery penetrate the levator labii muscle. Other perforating vessels on both borders of the midportion of the zygomatic major muscle assist in supplying the cheek skin adjacent to the ala. The flap may be designed as a peninsular flap based superiorly on a cutaneous pedicle or as an island based on a subcutaneous tissue pedicle. In most circumstances, I prefer to design the flap as a crescent-shaped island of skin based on a subcutaneous tissue pedicle. The superior extent of the island remains 5 mm below the alar-facial sulcus, preserving this important aesthetic area.9

An exact template of the alar unit is made from the contralateral normal side with a malleable material such as foil or a thin sheet of foam rubber. The template is reversed to design the interpolated cheek flap. When the defect extends beyond the confines of the ala into another nasal aesthetic unit, the template is designed slightly smaller than the defect to accommodate the phenomenon of distraction of wound margins, which creates an open wound that is larger than the surface area of the skin removed. If excision of additional skin is indicated to resurface an adjacent nasal aesthetic unit, the template is fashioned before the remaining skin is removed because of this same phenomenon. Alternatively, the contralateral intact nasal aesthetic unit can be used to design the template.

When the ala is reconstructed with a melolabial flap, the entire ala is resurfaced with the cheek flap, except for 1 mm of alar skin just anterior to the alar-facial sulcus (see Fig. 12-4). This small skin tag preserves the alar-facial sulcus and often provides a better scar than when the flap extends to the sulcus. This approach is similar to the method recommended by Sheen and Sheen13 for performing a type II Weir excision to reduce the size of the nasal base. Maintaining the excision outside of the alar-facial sulcus lessens the risk for development of a depressed scar. This approach also avoids the technically challenging requirements of integrating the flap into the nasal sill at the time of flap inset. When using cheek flaps for repair, I often delay excision of the extreme lateral portions of the residual alar skin until the time of pedicle detachment and flap inset. This delay reduces the wound tension on the flap at the time of initial transfer.

The fashioned template is placed on the melolabial fold so that the center of the flap is positioned 1 cm above the horizontal plane of the oral commissure. The template is positioned so that the medial border of the designed flap lies in the melolabial crease. This arrangement ensures that the flap is harvested from the cheek, not the lip, and that the donor site wound closure will lie within the melolabial crease, providing maximum scar camouflage. The flap is designed to pivot 90° toward the midline in a clockwise direction when it is harvested from the left cheek and counterclockwise when it is harvested from the right cheek. Thus, the template is positioned to design the flap with a specific orientation. As the flap is pivoted and transferred to the recipient site, the medial border of the in situ flap is sutured to the cephalic border of the nasal defect. This in turn causes the inferior border of the in situ flap to join the anterior border of the defect. The lateral border of the in situ flap becomes the inferior border of the reconstructed ala (see Fig. 12-4).

The lateral portion of the flap attached to the nose is released from attachments to the adjacent nasal skin for a distance of 0.5 to 1.0 cm to achieve sufficient freedom to unfurrow the flap. Release enables the surgeon to remove excessive subcutaneous fat not trimmed at the time of flap transfer. The residual skin of the alar unit is excised if present. However, a 1-mm fringe of skin at the junction of the ala and the alar-facial sulcus is preserved. The flap is precisely trimmed to fit the skin defect and sutured in place with simple interrupted 5-0 absorbable cutaneous sutures (see Fig. 12-4). When the alar base is absent, the flap is tailored to replace the missing base and is integrated with the nasal sill. When the sill requires reconstruction, the flap is trimmed so that it has a tapered end that may serve as the sill. The end is turned medially and sutured to the upper lip.

Melolabial Interpolated Cutaneous Pedicle Flaps

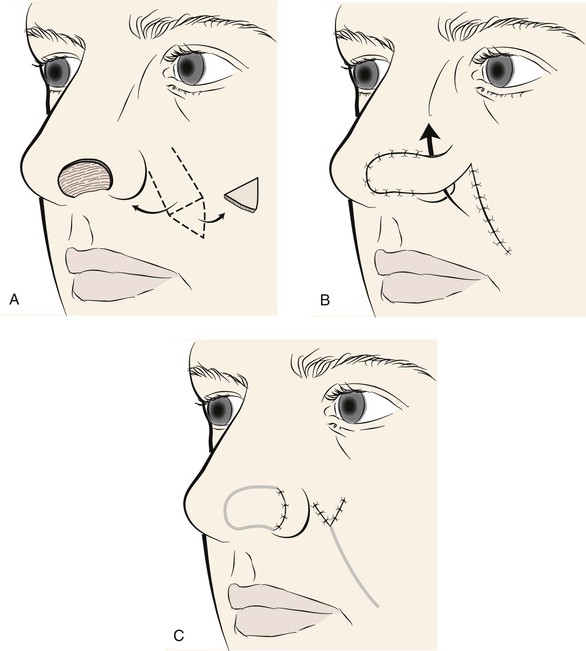

The peninsular flap depends on the dermal and subdermal vascular plexuses of the cutaneous pedicle to provide vascularity to the distal flap (Fig. 12-5). The cutaneous pedicle must have sufficient width and depth to ensure this vascularity. In designing a peninsular flap, the orientation of the template remains the same as for designing an island flap. The width of the cutaneous pedicle is approximately the width of the template, although it may be narrower than the template when a wide (more than 2 cm) flap design is required. The peninsular flap is elevated in a subcutaneous tissue plane, maintaining 3 mm of fat on the undersurface of the cutaneous pedicle. This is in contrast to the island design, based on a subcutaneous tissue pedicle that may be as much as 1.5 cm thick. Thus, the plane of dissection for the cutaneous pedicle flap is considerably more superficial. Like the island flap, the peninsular flap pivots 90° toward the midline and is sutured to the nose in a fashion similar to that described for the island flap. Care is taken not to kink the pedicle on transferring the flap. Like the island flap, the distal half of the peninsular flap may be thinned as necessary to replicate the thickness of the recipient site. The proximal portion of the flap bridging between the cheek and nose is not thinned to ensure a sufficient vascular supply. The cheek wound is closed by a method identical to that for the island flap.

FIGURE 12-5 A, Skin defect of nostril margin in zone between tip and ala. Cutaneous pedicle interpolated melolabial flap designed for repair. B, Flap transferred. Cutaneous pedicle crosses over alar-facial sulcus and ala. C, Second stage consists of division of pedicle and flap inset.

Similar to the island flap, the peninsular flap remains attached to the cheek for 3 weeks to enable the establishment of collateral vascularity. The pedicle is divided at a second stage, and the proximal portion of the pedicle is inset in the cheek by opening the superior portion of the donor site scar 1 to 2 cm. The wound edges are spread widely, creating a space to accommodate the proximal pedicle. The skin adjacent to the opened wound is undermined for 2 cm. This allows the cheek skin to retract, assisting in enlarging the wound. The pedicle stump is then trimmed to precisely fit the wound and inset in the melolabial fold, creating a V-shaped wound closure (see Fig. 12-5). Returning most of the skin of the proximal pedicle to the cheek helps maintain the natural fullness observed in the upper portion of the melolabial fold. Alternatively, the proximal pedicle may be amputated in an elliptical configuration and the cheek wound closed primarily. This has the advantage of a linear donor site scar within the melolabial crease. The distal portion of the flap left attached to the nose is thinned and inset by methods similar to those for the island flap. Less aggressive sculpturing of subcutaneous fat is recommended for patients who use tobacco products.

Case Reports

Case 1

A 56-year-old man presented with a 7 × 3.5-cm skin defect of the lower medial cheek after micrographic surgery for a basal cell carcinoma (Fig. 12-6). The defect was large and on initial inspection would indicate the need for a sizable local flap for repair, designed as either an advancement or a transposition flap. The medial inferior cheek has the greatest skin laxity of the face and provides a valuable source from which to transfer melolabial flaps. Manual manipulation of the margins of the defect suggested that primary wound closure was possible. The skin on either side of the wound was widely undermined in the subcutaneous tissue plane and the wound closed primarily. Standing cutaneous deformities resulting from the side-to-side advancement were excised parallel to the melolabial and labial mandibular creases. Advancement flaps are most effective in areas of greatest skin elasticity and redundancy like the melolabial fold and jowl. The most basic advancement flap is the one discussed in this case, in which simple linear layered wound closure in a side-to-side approximation is accomplished to close the defect primarily. No incision to create a flap is made.

FIGURE 12-6 A, A 7 × 3.5-cm skin defect of cheek repaired by advancement of wound borders. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformities marked by horizontal lines. B, Deformities excised and wound closed. C-F, Preoperative and 1.5-year postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

When incisions are required to create a unipedicle melolabial advancement flap to repair skin defects of the superomedial cheek, usually only one incision is necessary. This is made in or parallel to the melolabial crease. The skin of the fold is undermined in the subcutaneous tissue plane and advanced superiorly (see Fig. 12-2). Depending on the location of the cheek defect, the advancement flap may also be pivoted slightly to facilitate moving skin from the melolabial fold into the defect. An example of this is shown in Figure 12-7. The defect shown occurred after micrographic surgery to remove a basal cell carcinoma in an 83-year-old woman. The defect measured 3 × 2.5-cm. An advancement flap was designed to repair the wound by making a single incision parallel to the melolabial crease. The large standing cutaneous deformity forming as a result of the advancement of skin was excised lateral to the defect. This repair used a modified unipedicle advancement flap in which only one incision was made to dissect and advance the skin of the flap.

FIGURE 12-7 A, A 3 × 2.5-cm skin defect of medial cheek. B, Modified unipedicle melolabial advancement flap designed with only one side and with Z-plasty at base. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity marked at superolateral border of defect. C, Flap in place. D, Postoperative view at 6 months. No revision surgery performed.

Case 2

Transposition is the most common form of transferring skin of the melolabial fold as a local flap. Small to very large transposition flaps can be harvested from the melolabial fold, and closure of the flap donor site can usually be positioned in the melolabial crease (Fig. 12-8). Large transposition flaps are based superiorly to transfer skin from the inferior portion of the fold and the jowl region of the face where skin is more redundant. However, small skin defects of the medial cheek may be repaired with inferiorly or superiorly based melolabial transposition flaps. In such circumstances, depending on the direction of the pivot, the standing cutaneous deformity that forms from transposition can be excised in the melolabial crease. When the defect is positioned at the extreme superior and medial cheek near the lower eyelid and nose, the transposition flap must be based superiorly. In this circumstance, there is insufficient skin to construct an inferiorly based flap without extending the flap on the sidewall of the nose (Fig. 12-9).

FIGURE 12-8 A, A 1 × 1-cm cutaneous defect of medial cheek. Dufourmentel transposition flap designed for repair. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) marked for excision. B-D, Flap transferred. SCD excised. E, F, Postoperative result at 1 year. No revision surgery performed.

FIGURE 12-9 A, A 2 × 1.4-cm skin defect of medial cheek. Superiorly based melolabial transposition flap designed for repair. Standing cutaneous deformity marked for excision. B-D, Flap transferred. Standing cutaneous deformity excised. E, Preoperative and F, Postoperative result at 6 years. No revision surgery performed.

An inferiorly based melolabial transposition flap was used to repair the skin defect shown in Figure 12-10. The defect measured 1.8 × 1-cm and occupied a position between the cheek and the upper lip. The defect had an elliptical configuration, but primary wound closure would have been difficult because the defect abutted the alar base. Removal of the standing cutaneous deformity developing at the superior pole of the defect on wound closure would have necessitated excision of a portion of the alar base. For this reason, a Webster 30° triangulated transposition flap was used to reconstruct the defect. The majority of the wound closure suture line remained parallel to the melolabial crease.

FIGURE 12-10 A, A 1.8 × 1-cm cutaneous defect of medial cheek and lateral upper lip. Melolabial transposition flap designed for repair. B, C, Flap transferred and wound closed. D, E, Postoperative result at 18 months. Z-plasty scar revision performed 1 year after wound repair.

The note flap described by Walike and Larrabee is an angular transposition flap that, when designed, looks like a musical eighth note.14 There is a detailed discussion of the note flap in Chapter 8. Melolabial note flaps enable the surgeon to close circular defects with a triangle-shaped transposition flap that maximizes the use of surrounding tissue.15 The flap is designed by first drawing a tangent on either side of a circular skin defect parallel to RSTLs. The tangent should have the length of 1.5 times the diameter of the defect. At the end of the tangent line, a 50° to 60° angled flap is designed with the second side of the flap having a length approximately equal to the diameter of the circle.15 The flap is transposed into the defect, and the distal tip of the flap may be trimmed so that there is no wound closure tension. Figure 12-11 demonstrates how a modified inferiorly based melolabial transposition note flap was used to repair a 3 × 2-cm skin defect of the medial cheek. The design of the flap was modified by making the line tangent to the defect equal to the diameter of the defect instead of 1.5 times the diameter. This was done to prevent an incision crossing perpendicular to the melolabial crease. In the case shown, the tip of the flap was preserved and part of the wound was closed around the tip by advancing wound margins. This created a small standing cutaneous deformity that was excised at the junction of the nasal sidewall and the lower eyelid. As with rectangular and parabola-shaped transposition flaps, the greatest wound closure tension is at the donor site. In the case of the note flap, the greatest wound closure tension is approximately perpendicular to the tangent line created when the flap is designed. The surface area of the note flap is designed so that it is 25% less than the area of the defect; thus, clinical judgment is required when this flap is used. The flap is recommended primarily for small (2 cm or less) skin defects, although it worked well for the larger defect shown in Figure 12-11. Because the pivotal arc of the note flap is approximately 45°, a small standing cutaneous deformity develops that requires excision lateral to the defect.

FIGURE 12-11 A, A 3 × 2-cm skin defect of medial cheek. Inferiorly based melolabial transposition flap designed for repair. Anticipated standing cutaneous deformities marked medial and lateral to defect. Medial deformity resulted from partial closure of superior aspect of defect by advancement of wound borders. B, C, Flap incised, dissected, and transposed. D, Flap in place.

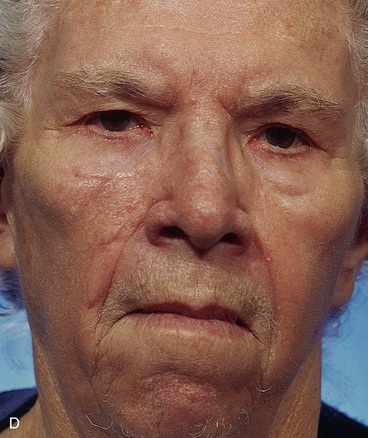

Case 3

A 62-year-old man had micrographic surgical excision of an extensive basal cell carcinoma of the medial cheek. The defect measured 8 × 8-cm and was contained within the aesthetic region of the cheek (Fig. 12-12). Because of the large size of the defect, the choice of reconstruction with a local cutaneous flap was restricted to the use of either a rotation or transposition flap. A rotation flap would have required dissection of the entire remaining skin of the cheek. In addition, the curvilinear incision necessary for the flap would have extended from the nose to the ear perpendicular to RSTLs. A superiorly based melolabial transposition flap was selected for repair of the wound. The flap was constructed of the lax skin of the jowl and was elevated in the subcutaneous tissue plane. The standing cutaneous deformity was excised lateral to the skin defect. The flap donor site was closed so the resulting scar for most of its length would parallel the melolabial crease. The patient’s postoperative photographs show obliteration of the melolabial fold because of the large size of the flap necessary for reconstruction of the defect. One of the disadvantages of melolabial transposition and interpolated flaps is the reduction of the fold and the resulting facial asymmetry. The larger the flap is, the greater is the flattening of the melolabial fold contour. In this case, facial asymmetry was unavoidable because the upper two-thirds of the fold had been resected with surgical excision of the skin cancer.

FIGURE 12-12 A, An 8 × 8-cm skin defect of medial cheek and alar base. Superiorly based melolabial transposition flap designed for repair. B, Flap transposed. Alar component of defect covered by full-thickness skin graft (not visible in photograph) obtained from excised standing cutaneous deformity of transposition flap. C, D, Postoperative views at 9 months. No revision surgery performed. (From Baker SR: Local cutaneous flap. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 27:139, 1994.)

Case 4

A 64-year-old woman developed a melanoma in situ of the right cheek. Surgical margins were established by the square technique (Fig. 12-13). This technique is described in detail in Chapter 8, Case 3. The skin planned for excision was outlined by linear scars and measured 4 × 3-cm. Reconstruction of the skin defect after resection of the melanoma could have been accomplished with a rotation flap. There was insufficient cheek skin medial to the defect to repair the wound with a melolabial transposition flap. To minimize the size of the rotation flap required for reconstruction, it was elected to use two local flaps, one with a rotation and the other with a transposition design. The flaps are shown in Figure 12-13C. A laterally based rotation flap and a superiorly based melolabial transposition flap were designed. The anticipated standing cutaneous deformity of the rotation flap is marked with vertical lines. The standing cutaneous deformity of the transposition flap developed superomedially and assisted the rotation flap with repair of the superior aspect of the defect. The use of two cutaneous flaps in place of one eliminated the need to design a much wider rotation flap, which by necessity would have extended above the medial canthus and would have placed more wound closure tension on the lateral canthus and lower eyelid. The intervening skin between the anticipated defect and the designed melolabial flap was transposed toward the lip, thus creating a large Z-plasty repair (Fig. 12-13D). Figure 12-14A shows an 8-month postoperative photograph of the repair. Trap-door deformity of the transposition flap was persistent and necessitated contouring of the flap and Z-plasties of the scars. The Z-plasties are shown in Figure 12-14B, C. The techniques of revision surgery of local flaps are discussed in detail in Chapter 27. The final results of the reconstruction are shown in Figure 12-14D, E.

FIGURE 12-13 A, B, A 4 × 3-cm planned skin excision marked by linear scars. C, Laterally based rotation flap and superiorly based melolabial transposition flap designed for repair of anticipated defect. Standing cutaneous deformity of rotation flap marked with vertical lines. D, Skin adjacent to transposition flap pivoted inferiorly to create Z-plasty. E, Flaps in place. Transposition flap represents a modified Z-plasty.

FIGURE 12-14 A, Same patient shown in Figure 12-13 at 8 months after surgery. Trap-door deformity of transposition flap observed. B, C, Z-plasties of scars and contouring of transposition flap performed. D, E, Result 11 months after revision surgery.

Case 5

In general, skin-only defects of the lip are best repaired with skin flaps designed and transferred within the confines of the aesthetic region of the lip. This maintains scars along aesthetic boundaries and maximizes the match of skin color, texture, and hair growth patterns. However, when skin-only defects of the lip are very large, there is insufficient remaining skin within the lip aesthetic region to repair the wound. In these circumstances, the only alternative for repair is the use of a full-thickness skin graft or cheek skin in the form of a transposition or advancement flap. Such was the circumstance in the patient shown in Figure 12-15. Most of the skin of the upper lip was removed with micrographic surgery for a basal cell carcinoma while the underlying muscle was spared. The defect measured 5 × 3-cm. It is the author’s opinion that full-thickness skin grafts should be used to repair lip defects only as a last resort because of the poor texture match with the remaining lip skin and the tendency toward scar contracture and subsequent deformation of the vermilion. In general, transposition flaps rather than advancement flaps from the cheek work best for repair of skin defects of the lip because the donor site scar remains in or parallel to the melolabial crease. In contrast, advancement flaps that extend to the lip from the cheek usually cross the melolabial crease at right angles.

FIGURE 12-15 A, B, A 5 × 3-cm skin-only defect of upper lip. Superiorly based melolabial transposition flap designed for repair. Remaining skin of right lateral aesthetic unit of lip marked for excision. C, Postoperative view at 3 months. Standing cutaneous deformity was not excised and is adjacent to alar base.

A superiorly based melolabial transposition flap was selected for repair of this patient. The remaining skin of the lateral aesthetic unit of the lip between the cheek and the lip was removed to position scars along the vermilion and in the alar-facial sulcus. This also allowed the resurfacing of the entire lateral lip aesthetic unit. Because of the large size of the flap, it was elected not to completely excise the standing cutaneous deformity during the initial transfer of the flap. The deformity formed adjacent to the nose and is seen in Figure 12-15C. This figure also shows the typical trap-door deformity that frequently develops in transposition flaps in the early stages of healing. A secondary contouring of the flap and removal of the standing cutaneous deformity was performed 3 months later. The patient also required two Z-plasties of the vertical scar of the central lip (Fig. 12-16).

FIGURE 12-16 A-D, Same patient shown in Figure 12-15. Preoperative and 5-year postoperative views after revision surgery consisting of excision of standing cutaneous deformity and Z-plasties of vertical scar of central lip.

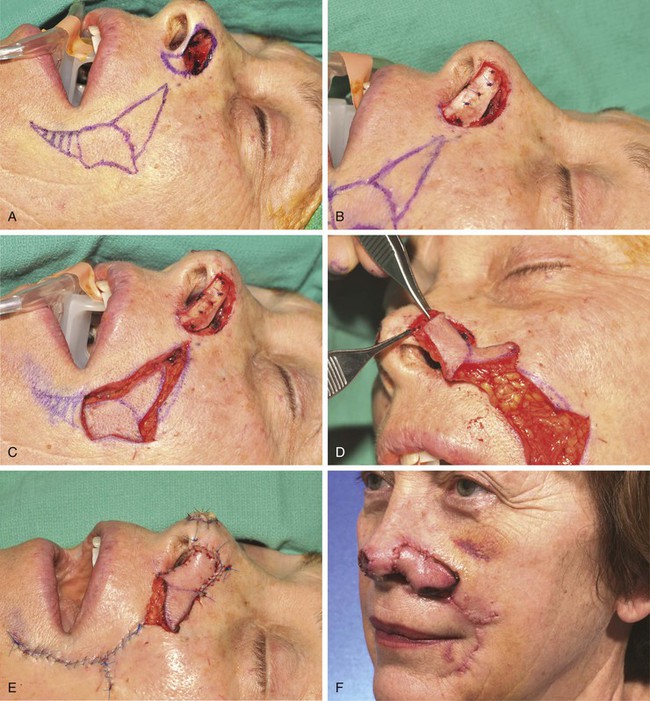

Another patient with a defect of the upper lip reconstructed with a large melolabial transposition flap is shown in Figure 12-17. This defect measured 4 × 3.5-cm and was more complex than the preceding case. The defect was deeper with loss of soft tissue and muscle of the upper lip and loss of the entire nasal sill, floor of the nasal vestibule, and base of the ala after micrographic surgery for a basal cell carcinoma. Whenever defects involve the upper lip and the base of the nose, it is often prudent to reconstruct the defect in stages. The lip is always repaired first to provide a platform on which to rest the nose. The nasal defect is reconstructed second, once the lip is completely healed and the scars of the lips are maturing and not likely to suffer further contraction (4-6 months).

FIGURE 12-17 A, B, A 4 × 3.5-cm skin and muscle defect of upper lip, alar base, nasal sill, and floor of nasal vestibule.

A superiorly based melolabial transposition flap (Fig. 12-18) was selected for repair of the defect. The small parabola marked at the superomedial border of the flap represents that portion of the flap designated to line the floor of the nasal vestibule. The remaining ala was sutured to the flap simply to facilitate closure of the raw surface of the ala and with the intent of reconstructing the alar base by subsequent separation of the flap from the ala. A piece of auricular cartilage was placed within the depths of the nasal vestibular defect to prevent medial dislocation of the ala from scar contracture (Fig. 12-18A). Because of the large size of the flap necessary for reconstruction, the lip defect was not enlarged by removing the remaining skin of the lateral aesthetic unit of the lip. The transposition flap was dissected in the subcutaneous tissue plane. The dissection was deepened superomedially to convey extra cheek fat with the flap so that it could be used to fill the depths of the deep defect located at the base of the nose. The flap donor site was closed by advancement creating a scar parallel to the melolabial crease. In this case, the standing cutaneous deformity that formed during transposition of the flap was not excised but used to assist the closure of the defect. The deformity provided bulk and skin for restoration of the floor of the nose.

FIGURE 12-18 A, Superiorly based melolabial transposition flap designed for repair of defect of patient shown in Figure 12-17. Auricular cartilage graft is spanning defect between remaining ala and floor of nasal vestibule. Small parabola marked at superomedial border of flap represents that portion of flap designated to line floor of nasal vestibule. Horizontal lines mark anticipated standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) resulting from closure of flap donor site. B, Flap transposed. Bolster dressing used to compress flap against floor of nasal vestibule. Remaining ala sutured to standing cutaneous deformity left intact after transposition of flap. C, At 5 months after first stage of reconstruction. Standing cutaneous deformity of flap obliterates alar-facial sulcus and superior portion of melolabial crease. Deformity was detached from ala and trimmed of excess fat and skin 4 months later in second surgical stage.

Four months later, the standing cutaneous deformity at the base of the nose was detached from the ala, trimmed of excessive skin and fat, and contoured so that it restored the normal configuration of the nasal sill and floor of the vestibule. Three months later, a third surgical stage was performed. In this stage, the base of the ala was reconstructed with a composite auricular graft that was inserted between the remaining ala and the reconstructed lip. Additional contouring of the transposition flap was also performed in an attempt to restore the melolabial crease and the natural contour of the lateral upper lip. A small persistent standing cutaneous deformity at the inferior aspect of the flap donor site was also trimmed. Figure 12-19 shows the repair 1 day after the third stage of the reconstruction. Quilting sutures are seen in the area of previously transferred flap. These were used to eliminate dead space and to prevent hematoma after undermining of the flap and removal of redundant subcutaneous fat. A pale composite graft is also seen at the base of the ala. Figure 12-20 shows the completion of the reconstruction of the lip and nose. The asymmetry of the face resulting from use of the melolabial flap is minimal, and the flap donor site scar is well camouflaged by remaining in RSTLs.

FIGURE 12-19 A, B, One day after third surgical stage of patient shown in Figure 12-17. During this stage, base of ala reconstructed with composite auricular graft seen as segment of pale tissue inserted between remaining ala and reconstructed lip. Additional contouring of transposition flap also performed to restore melolabial crease and more natural contour of upper lip. Quilting sutures are observed in area of flap contouring. Small persistent standing cutaneous deformity removed from extreme inferior aspect of flap donor site.

FIGURE 12-20 A, B, Same patient shown in Figure 12-17 at 9 years after three-stage surgical reconstruction.

The two patients discussed in this case study demonstrate the usefulness of large melolabial transposition flaps for repair of extensive skin defects of the upper lip. Such flaps can also be used for similar defects of the lower lip (see Chapter 8, Case 8). Although large, the flap donor defects were closed primarily and the resulting scars were unobtrusive once healing had occurred. These patients also demonstrate the versatility of the melolabial flap. In the second patient, the flap was used to line the floor of the nose, to provide a foundation for the alar base, and to resurface the lip defect.

Case 6

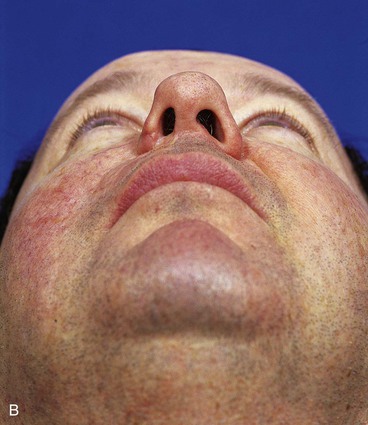

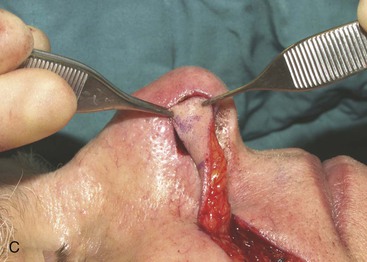

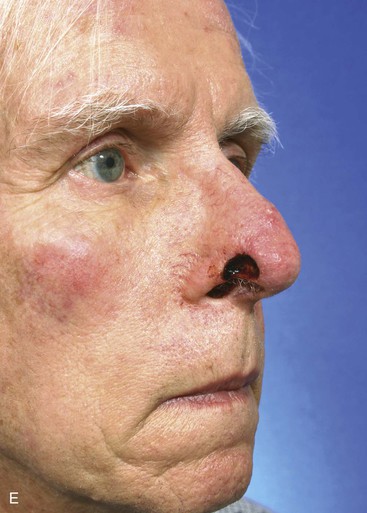

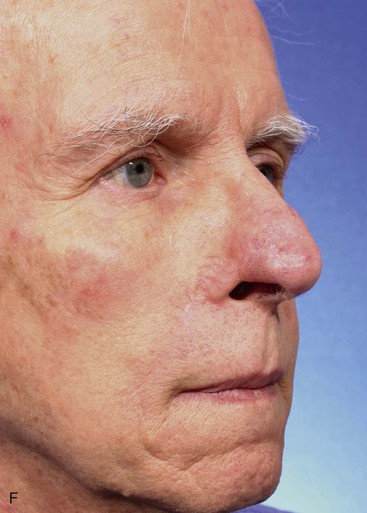

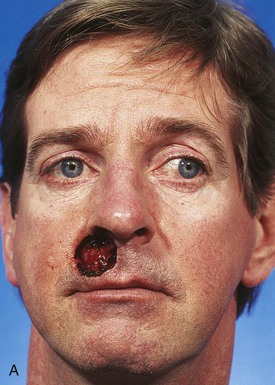

A 69-year-old woman presented with a 1 × 1-cm superficial skin defect of the right nasal tip and a 1.5 × 2-cm skin and deep soft tissue loss of nearly the entire left ala after micrographic surgical excision of two independent basal cell carcinomas (Fig. 12-21). The defect extended to the depth of the nasal mucosa but not through it. Because of the proximity of the ala to the melolabial fold, skin defects of more than half of the surface area of the ala are ideally reconstructed with an interpolated melolabial flap. The flap provides skin nearly identical in color, thickness, and texture to native alar skin. A melolabial flap with an interpolated design was selected for repair of the wound rather than a transposition flap for reasons discussed in an earlier section of this chapter. The interpolated flap was designed as a subcutaneous tissue pedicle island flap because the flap tends to be more reliable than a cutaneous base interpolated flap. The remaining skin of the alar aesthetic unit was removed, and an auricular cartilage graft was sculpted and inserted in the wound so that it extended from the alar base to the nasal facet (Fig. 12-22B). It was secured to the underlying vestibular skin with mattress sutures. The melolabial flap is shown drawn so that the major portion of the flap is centered just lateral and superior to the level of the lateral oral commissure (Fig. 12-22A). The anticipated inferior standing cutaneous deformity resulting from closure of the flap donor site is marked in Figure 12-22A. This triangular piece of skin is excised and discarded during wound closure. The triangle of skin marked at the superior border of the flap also represents a standing cutaneous deformity that forms from closure of the donor site wound. However, this triangle is left attached to the flap and is excised and discarded when the flap pedicle is divided and the flap inset at 3 weeks after initial transfer to the nose. A third surgical stage consisting of a contouring procedure to thin the flap and to restore the alar groove was performed. This technique is discussed in detail in Chapter 18. Figure 12-23 shows the postoperative results after the third surgical stage. The scar on the cheek lies in the melolabial crease, and there is minimal deformation of the melolabial fold. The alar-facial sulcus has a natural appearance because it was left undisturbed by use of an interpolated rather than a transposition melolabial flap.

FIGURE 12-22 A, Same patient shown in Figure 12-21. Remaining skin of ala marked for excision. Melolabial interpolated subcutaneous tissue pedicled flap designed for repair. Center of flap is lateral and superior to level of oral commissure. Medial border of flap is designed to lie in melolabial crease. Triangle of skin at superior border of flap represents standing cutaneous deformity (SCD) resulting from closure of donor defect. This is transferred with flap and removed when flap is inset. Horizontal lines mark anticipated second standing cutaneous deformity inferior to flap. This deformity is excised and discarded during closure of donor defect. B, Auricular cartilage graft positioned to span gap between alar-facial sulcus and nasal facet. C, In situ flap incised. D, Flap is pedicled on ample subcutaneous fat of melolabial fold. E, Flap in position. F, One week after first-stage reconstruction.

FIGURE 12-23 A-C, Same patient shown in Figure 12-21 at 6 months after reconstruction of ala. Flap contouring procedure performed 3 months after flap inset.

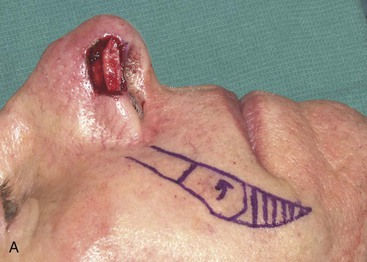

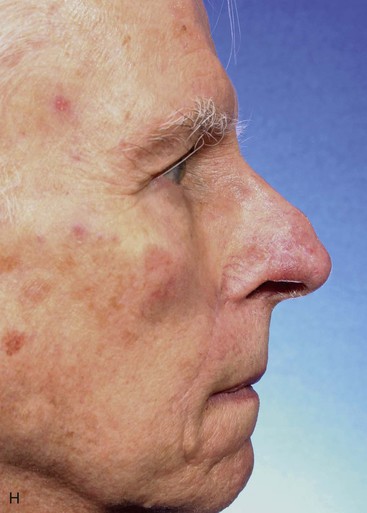

The author selects a subcutaneous tissue pedicle island flap for the majority of nasal reconstruction cases requiring an interpolated melolabial flap. However, a cutaneous pedicle peninsular flap is often used for reconstruction of skin defects of the ala or nostril margin that do not require resurfacing of the entire aesthetic unit of the ala. The patient shown in Figure 12-24 is an example of this. The defect resulting from micrographic excision of a basal cell carcinoma was more superficial than the defect described in the preceding patient and was nearly confined to the nostril margin. For this reason, a cutaneous pedicle interpolated melolabial flap was selected for repair (see Fig. 12-24). To create right-angle corners to the defect, 1 mm of skin was removed from the border of the wound. The angulated corners of the defect help prevent trap-door deformity. An auricular cartilage graft was positioned to span the defect of the nostril margin. A rectangular melolabial interpolated flap was designed and dissected by the same methods discussed earlier except that the cutaneous pedicle was maintained rather than creating a skin island. The flap was dissected in a more superficial tissue plane because it was dependent for its vascular supply not on subcutaneous fat but rather its cutaneous attachment. Three weeks after flap transfer, it was inset by dividing and discarding the cutaneous pedicle. The wound from excision of the pedicle was closed in the superior melolabial crease lateral to the alar-facial sulcus, which was left undisturbed by the reconstructive process. The 6-month postoperative results are shown in Figure 12-24. The donor site scar of the melolabial flap is perfectly positioned within the aesthetic boundary of the melolabial crease for maximum scar camouflage. The melolabial interpolated flap is a valuable method of resurfacing nasal defects, particularly for repair of skin defects of the ala, columella, and caudal nasal sidewall. For an in-depth discussion of nasal reconstruction, the reader is directed to Chapter 18.

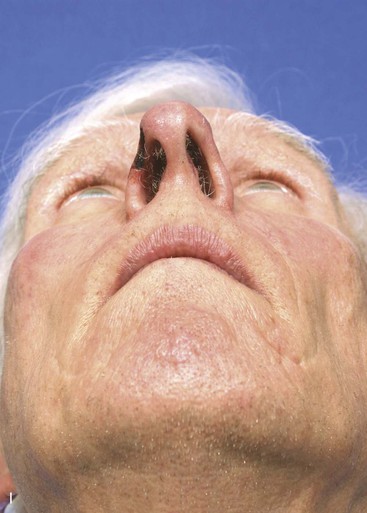

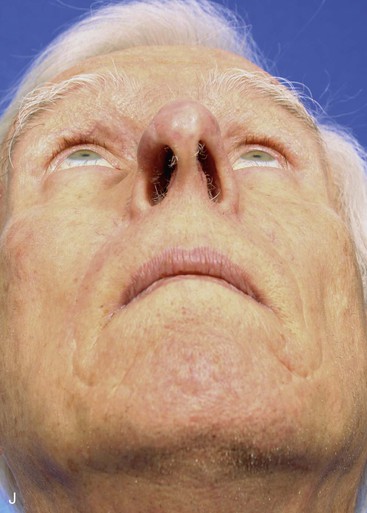

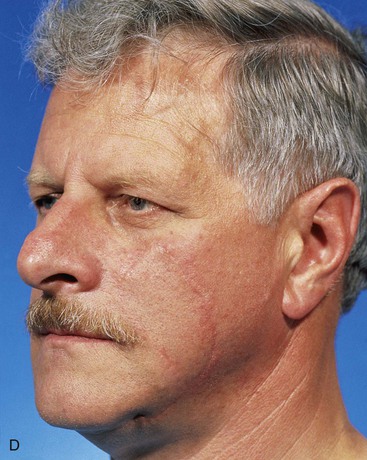

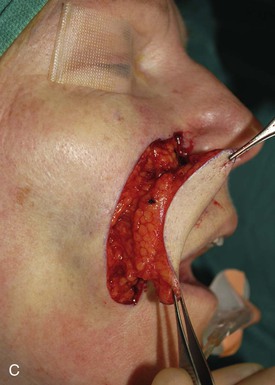

FIGURE 12-24 A, A 1.5 × 1-cm skin and soft tissue defect of nostril margin. Melolabial interpolated cutaneous pedicle flap designed for repair. Auricular cartilage graft has been positioned to span nostril margin defect. B, In situ flap incised. C, Flap transferred to nose on cutaneous pedicle. D, Flap in place. E-J, Preoperative and 6-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

Case 7

Transposition flaps are the most common local flap harvested from the melolabial fold. In the author’s practice, the subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap is the second most common melolabial flap used. The indications and techniques for dissecting this flap are discussed in an earlier portion of the chapter. Presented are two cheek defects repaired by melolabial V-Y subcutaneous tissue pedicled island advancement flaps.

A 57-year-old man presented with a rectangular skin defect having a long diagonal of 6 cm and a short diagonal of 5 cm (Fig. 12-25). The defect resulted from surgical resection of a superficial spreading melanoma. The three best options for repair of the defect with a local flap included transposition and rotation pivotal flaps and a melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap. The island flap was selected for repair because of the redundancy of skin in the jowl that could be used for construction of the flap. Figure 12-25 shows the design of the flap and the flap in place. A great advantage of the subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap is that no significant standing cutaneous deformity is created and so excision of facial skin is not necessary. This is in marked contrast to transposition and rotation flaps. If such flaps had been used in this case, large standing cutaneous deformities would form on pivoting of the flaps. These deformities would have required excision, discarding valuable facial skin in a patient who had already lost a large portion of his cheek skin from resection of the skin cancer. Figure 12-26 shows the preoperative and 3-month postoperative views of the reconstruction. The majority of scars rest in RSTLs, and there is minimal deformation of the melolabial fold.

FIGURE 12-25 A, A 5 × 4-cm medial cheek defect. Melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap designed for repair. Borders of designed flap parallel melolabial crease. B, Flap in place and donor site closed.

FIGURE 12-26 A-D, Same patient shown in Figure 12-25, preoperative and 3-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

A 39-year-old patient was also treated for a basal cell carcinoma of the medial cheek. The tumor was treated with micrographic surgical excision, resulting in a 2.5 × 2.6-cm cutaneous defect. The defect is shown in Figure 12-27, in addition to the design of a melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap. The flap was designed to use skin of the melolabial fold. The medial border of the flap was designed so that it was within the melolabial crease. Island advancement flaps have the greatest mobility and thus are most useful when designed in areas having ample subcutaneous fat. Relative to the remaining face, the melolabial fold contains the greatest amount of fat, making the fold an ideal donor site for island flaps. The ample subcutaneous tissue on which to base the flap and the marked mobility of the melolabial island flap are demonstrated in Figure 12-27C. As was noted in the preceding patient, excision of a standing cutaneous deformity was not necessary, so all facial skin was preserved except for that required to resect the skin cancer. Figure 12-28 shows the preoperative and 1-year postoperative views of the reconstruction. Minimal deformation of the melolabial fold is observed on the frontal and oblique postoperative views.

FIGURE 12-27 A, A 2.5 × 2.6-cm skin defect of medial cheek. Melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap designed for repair of wound. Stippled area represents extent of flap undermining in subcutaneous plane. B, In situ flap incised. C, Ample subcutaneous tissue pedicle provides mobility to skin island. D, Flap in place and donor defect closed.

FIGURE 12-28 A-D, Same patient shown in Figure 12-27, preoperative and 1 year postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

Case 8

The melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap is most effective for repairing 3-cm to 6-cm skin defects of the medial cheek adjacent to the alar base. It is also useful for repair of lateral upper lip skin defects that extend into the adjacent cheek.16 In such circumstances, skin from the melolabial fold is recruited into the island flap along with any remaining lip skin lateral to the defect. Presented are two cases of large lateral upper lip defects that were repaired with melolabial island advancement flaps.

The first patient, a 73-year-old woman, had an excision of a 3 × 2.5-cm area of skin of the upper lip and medial cheek to remove a basal cell carcinoma. A melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap was designed for repair of the defect (Fig. 12-29). The island flap was dissected by surgical techniques similar to those discussed earlier except that the portion of the flap consisting of lip skin was undermined to free the lip skin from its attachment to the orbicularis oris. For melolabial island flaps including lip skin, the dissection requires freeing the skin of the island from any muscle attachments to the orbicularis oris. The flap is based on the ample subcutaneous fat lateral to the orbicularis oris. Figure 12-29C demonstrates the flap’s subcutaneous tissue pedicle and the mobility that the pedicle provides to the flap.

FIGURE 12-29 A, A 2.5 × 3-cm skin defect of upper lip. Melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap designed for repair. B, In situ flap incised. C, Subcutaneous tissue pedicle lateral to orbicularis oris provides mobility to flap. D, Flap in place and donor defect closed. E-H, Preoperative and 10-month postoperative views. Scar revision performed 7 months postoperatively.

A second patient reconstructed with a melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap consisting of skin of the lip and the melolabial fold is shown in Figure 12-30. The patient, a 41-year-old man, presented with a 5-year history of a tumor of the upper lip and nasal sill. Biopsy of the lesion revealed a basal cell carcinoma. The tumor was resected by micrographic excision, resulting in a skin and muscle defect of the upper lip measuring 3.5 × 2.5-cm. As in the preceding example, there was insufficient upper lip skin remaining for reconstruction of the defect without recruitment of skin from the melolabial fold. Similar to the preceding example, a melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap was used to repair the wound. The skin inferior to the defect was removed to the level of the vermilion to position the border of the flap along the vermilion (Fig. 12-30B). The ample subcutaneous tissue pedicle is demonstrated in Figure 12-30C. Enlargement of the defect to facilitate positioning of the border of the island flap along an aesthetic boundary provided maximum scar camouflage as noted in the early postoperative results seen in Figure 12-31B.

FIGURE 12-30 A, A 3.5 × 2.5-cm skin and muscle defect of upper lip and nasal sill. B, Melolabial subcutaneous tissue pedicle island advancement flap designed for repair. Skin inferior to lip defect marked for excision to enlarge defect so inferior border of flap will be along vermilion-cutaneous aesthetic boundary. C, Flap based on subcutaneous fat lateral to orbicularis oris. D, Postoperative result at 1 day. Lateral border of flap parallel to melolabial crease.

FIGURE 12-31 A, B, Same patient shown in Figure 12-30. Preoperative and 3-month postoperative views. No revision surgery performed.

References

1. Cameron, RR, Latham, WD, Dowling, JA. Reconstruction of the nose and upper lip with nasolabial flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1973; 52:145.

2. Pers, M. Cheek flaps in partial rhinoplasty. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967; 1:37.

3. Cameron, RR. Nasal reconstruction with nasolabial cheek flaps. In: Grabb WC, Myers MB, eds. Skin flaps. Boston: Little, Brown, 1975.

4. Clevens, RA, Baker, SR. Defect analysis and options for reconstruction. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1997; 30:495.

5. Baker, SR. Reconstruction of facial defects. In Cummings CW, Fredrickson JM, Harker LA, et al, eds.: Otolaryngology—head and neck surgery, 3rd ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 1998.

6. Baker, SR. Local cutaneous flaps in soft tissue augmentation and reconstruction in the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1994; 27:139.

7. Rustad, TJ, Hartshorn, DO, Clevens, RA, et al. The subcutaneous pedicle in melolabial reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998; 104:1163.

8. Burget, GC, Menick, FJ. Aesthetic restoration of one-half the upper lip. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986; 78:583.

9. Baker, SR, Johnson, TM, Nelson, BR. The importance of maintaining the alar facial sulcus in nasal reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995; 101:617.

10. Fader, DJ, Baker, SR, Johnson, TM. The staged cheek-to-nose interpolated flap for reconstruction of the nasal alar rim/lobule. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:644.

11. Burget, GC, Menick, FJ. Nasal support and lining: the marriage of beauty and blood supply. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989; 84:189.

12. Herbert, DC. A subcutaneous pedicled cheek flap for reconstruction of alar defects. Br J Plast Surg. 1978; 31:79.

13. Sheen JH, Sheen A, eds. Aesthetic rhinoplasty. 2nd ed. Mosby, St. Louis, 1987:255.

14. Walike, JW, Larrabee, WF, Jr. The note flap. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985; 111:430.

15. Larrabee, WF, Jr. Design of local skin flaps. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1990; 23:899.

16. Griffin, G, Weber, S, Baker, SR. Outcomes following V-Y advancement flap reconstruction of large upper lip defects. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012; 14:193.