Chapter 36 Melanoma

Introduction

The utility of imaging studies in patients with melanoma generally depends on the melanoma stage. There is little, if any, role for comprehensive imaging in patients with early-stage disease where surgery is often curative.1 Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy is generally first performed to identify site(s) of regional nodal drainage, including those patients with multiple draining nodal basins as well as to locate unpredictable nodal basins outside the standard nodal basins. Intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy provide accurate staging of melanoma patients with no clinically detectable nodal disease.2 Hematogenous dissemination is more likely in advanced regional disease and can occur in any organ system and, unfortunately, at any time. For distant metastases, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the dominant imaging modalities in general use. Ultrasound is commonly performed to evaluate surgical scars, new palpable lesions, lymph nodes with equivocal findings on other examinations, and/or lymph node basins at risk for metastatic disease. Positron-emission tomography (PET)/CT has an extremely limited, if any, role in patients with early disease (stages I and II) with no current universally accepted role for routine use.3 It can be used in patients with potentially resectable stage IV disease to exclude other sites of disease and for problem-solving for equivocal findings on other imaging studies. Imaging, therefore, plays an important role in staging, treatment planning, and posttreatment follow-up of patients with melanoma.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

Epidemiology

Melanoma accounts for 4% to 5% of new cancer diagnoses in the United States and is the fifth and sixth most common new cancer diagnoses in men and women, respectively.4 It is estimated that there will have been 70,230 new cases of melanoma diagnosed, and 8790 deaths from melanoma in 2011.4 The lifetime risk for developing melanoma is approximately 1 in 50.5 Furthermore, its incidence continues to increase throughout much of the world. Although the exact etiology for these epidemiologic trends is not entirely clear and certainly multifactorial, the rising incidence is thought to be at least partly related to increased sun exposure and early detection through screening programs.

The incidence of melanoma also has a notable geographic variation, with the highest incidence in Australia/New Zealand, followed by Europe and North America, respectively. Whereas the reasons for this are multiple and likely multifactorial, it is likely at least in part due to the sun exposure and fair skin complexions of populations in these countries.6

Risk Factors

In men, approximately one third of melanomas are on the trunk, most commonly the back, and in women, the most common site is in the lower extremities (42%).7 These distributional differences may reflect sun exposure patterns between the sexes.

Melanomas are generally associated with nevi, particularly dysplastic nevi. A family history of melanoma is also associated with an increased risk, possibly because of mutations in CDKN2A and CDK4 genes. A variety of susceptibility genes have also been identified.7

Anatomy and Pathology

Anatomy

Melanomas are derived from melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in skin, and are of neural crest origin. These cells are distributed widely throughout the skin as a result of their embryologic origin. Melanocytes can also be found in other sites and give rise to uncommon primary melanomas. Examples of noncutaneous sites in which melanomas occur include the eye (e.g., conjunctiva, retina, and uveal tract) and mucosae (e.g., anal, buccal, and nasal).8 Primary visceral melanoma is extremely rare but has also been reported.9–11

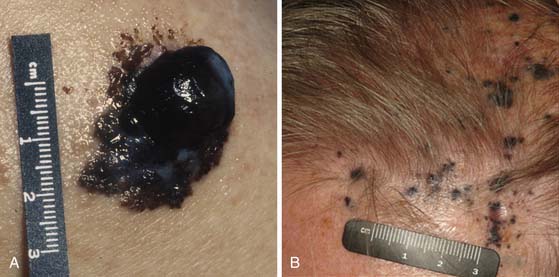

Melanomas typically contain melanin, which accounts for their characteristic dark appearance (Figure 36-1). However, some melanomas do not contain obvious visible melanin and are termed amelanotic.

Pathology

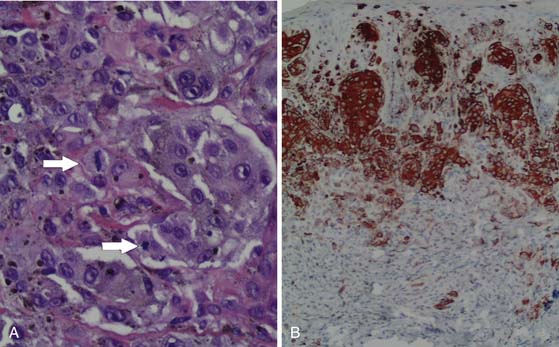

Although the appearance of some cutaneous lesions is highly suggestive of melanoma, definitive diagnosis is based on histologic assessment of the primary lesion. In general, the diagnosis of melanoma is based on a combination of standard hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining as well as confirmatory immunohistochemical studies using, for example, antibodies against melanocytic antigens such as S100 protein, melan-A, or gp100 (as detected by the antibody HMB45) (Figure 36-2). HMB45 can help distinguish melanoma in situ from sun-damaged skin/pigmented actinic keratosis. A confluent pattern of growth is observed with melanoma in situ compared with scattered atypical melanocytes found in sun-damaged skin or a pigmented actinic keratosis.12

Cutaneous melanomas typically grow from the epidermis toward the subcutaneous tissues (through papillary dermis, then reticular dermis, then subcutaneous tissues). The risk of metastatic disease and the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma are associated with the thickness of the primary lesion at the time of diagnosis, the presence or absence of primary tumor ulceration, and mitotic rate; hence, the need for careful histologic evaluation of the primary melanoma is paramount. The degree of proliferation of melanocytes is an important prognostic marker, for which the proliferation marker Ki-67 may also be employed.12

Key Points Anatomy and pathology

• Melanomas are derived from melanocytes, originating from the neural crest.

• Melanomas typically contain melanin, but some do not contain significant amounts of melanin and are classified as amelanotic.

• Melanomas most commonly arise in the skin and may arise in other areas (e.g., eye and mucosae).

• Diagnosis must be confirmed histologically.

• Tumor thickness is a key prognostic marker in cutaneous melanoma.

• Other primary tumor prognostic markers include ulceration and mitotic rate.

Clinical Presentation

The vast majority of patients with cutaneous melanoma present with a new or changing skin lesion that can occur essentially anywhere on the body. These are typically, but not always, darkly pigmented; pigmentation may be heterogeneous or homogeneous. Lesions may or may not be raised and nodular (see Figure 36-1). The diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma on clinical examination is fraught with difficulty and error; a reliable diagnosis of melanoma requires biopsy and histopathologic evaluation. Biopsies should be strongly considered for any pigmented lesions that have a change in color, size, or morphology. The ABCDEs of lesion classification as described by Rigel and coworkers13 may be used to identify skin lesions suspicious for melanoma and deserving of biopsy. “A” describes asymmetry, “B” describes border irregularity, “C” is for color variegation, “D” denotes a diameter greater than 6 mm, and “E” is for a lesion that is evolving or enlarging. A small subset of skin lesions ultimately confirmed to be melanoma that are not hyperpigmented are classified as amelanotic. In some patients with a newly diagnosed primary melanoma, a synchronous or second primary can be found.

In-transit and satellite metastases, defined as cutaneous or subcutaneous metastatic deposits between the primary tumor and the regional nodes may occur, represent a clinically relevant form of lymphatic metastasis in patients with melanoma. This pattern of recurrence is found in 3% to 12% of patients with melanoma.14

Patterns of Tumor Spread

Lymphoscintigraphy is used for localization of sentinel lymph nodes before surgery. The sentinel lymph node is the first draining lymph node on the afferent lymphatic pathway from the primary tumor. However, more than one pathway (i.e., more than one sentinel node and/or regional nodal basin) may drain a primary tumor. Nodes that are found along the course of a lymphatic pathway between the primary melanoma and the recognized regional nodal field(s) are termed interval (in-transit) nodes.15 Uren and colleagues15 found that interval nodes were more common in truncal melanomas than in those found in the lower limbs. Recognition of interval nodes is clinically important; they along with sentinel nodes in defined regional nodal basins should be removed during surgery because the interval node may be the only node containing metastatic disease. Thompson and associates16 found 13 of 4262 patients (0.31%) with primary melanomas of the distal lower extremities to develop popliteal nodal metastases. Because popliteal nodal involvement from melanoma is uncommon, indications for popliteal nodal dissection include a positive histologic popliteal fossa sentinel node or clinical detection of popliteal nodal disease.16 Uren and coworkers17 observed the drainage pathway to the epitrochlear region was seen in 36 of 218 patients (16%) with melanomas on the forearm and hand.

A feature of lymphatic dissemination in cutaneous melanoma, which is not commonly seen in other tumors, is “in-transit” disease. In-transit disease is the presence of cutaneous or subcutaneous melanoma deposits located between the primary tumor and the regional draining nodal basin. Risk factors for in-transit disease include age older than 50, a lower extremity primary tumor, increasing Breslow depth, ulceration, and positive sentinel lymph node status.14,18–21

Primary uveal melanoma, unlike primary cutaneous melanoma, tends to preferentially metastasize hematogeneously (rather than via lymphatics), most commonly to the liver. In patients with metastatic uveal melanoma, the liver is involved in 71.4% to 87% of patients. Liver metastases can appear up to 15 years after the initial diagnosis of the primary uveal melanoma.22–25 Uveal melanoma cells have been shown in studies to express receptors (e.g., c-Met, insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and CXCR4) for ligands (e.g., hepatocyte growth factor, insulin-like growth-factor-1 and stromal-derived factor-1) produced in the liver. The binding of these receptors and ligands contributes to cell growth and motility and increased invasiveness.26

Key Points Tumor spread

• Lymphatic dissemination typically precedes hematogenous spread, most commonly to regional nodes.

• Satellite and in-transit metastases—defined as cutaneous or subcutaneous metastatic deposits between the primary tumor and the regional nodes—may occur and represent a clinically relevant form of lymphatic metastasis in patients with melanoma.

• Risk factors for in-transit metastases include age older than 50, lower extremity primary tumor, increasing Breslow depth, ulceration, and positive sentinel lymph node status.

• Hematogenous metastases may occur anywhere, although “common” sites of distant metastatic melanoma include lung, soft tissue, liver, and brain.

Staging and Prognosis

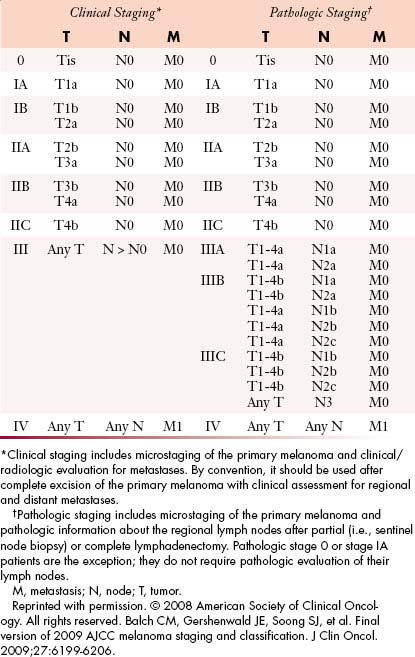

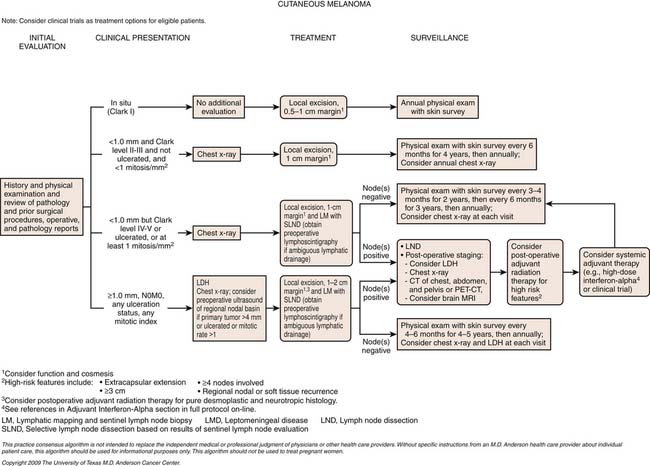

The TNM (tumor-node-metastases) classification is used for staging melanoma. The sixth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging for cutaneous melanoma published in 2002 has been superseded by the seventh edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, published in 2009 and implemented in January 2010.27 Assessment of the primary tumor and the presence or absence of regional nodal and distant metastases are the basis for staging (Tables 36-1 and 36-2 and Figure 36-3).

Table 36-1 Tumor-Node-Metastasis Staging Categories for Cutaneous Melanoma

| CLASSIFICATION | THICKNESS (mm) | ULCERATION STATUS/MITOSES |

|---|---|---|

| T | ||

| Tis | NA | NA |

| T1 | ≤1.00 | a Without ulceration and mitosis < 1/mm2 |

| b With ulceration or mitoses ≥ 1/mm2 | ||

| T2 | 1.01-2.00 | a Without ulceration |

| b With ulceration | ||

| T3 | 2.01-4.00 | a Without ulceration |

| bWith ulceration | ||

| T4 | >4.00 | a Without ulceration |

| b With ulceration | ||

| NO. OF METASTATIC NODES | NODAL METASTATIC BURDEN | |

| N | ||

| N0 | 0 | NA |

| N1 | 1 | a Micrometastasis* |

| b Macrometastasis† | ||

| N2 | 2-3 | a Micrometastasis* |

| b Macrometastasis† | ||

| c In-transit metastases/satellites | ||

| without metastatic nodes | ||

| N3 | 4+ metastatic nodes, or matted nodes, or in-transit metastases/satellites with metastatic nodes | |

| SITE | SERUM LDH | |

| M | ||

| M0 | No distant metastases | NA |

| M1a | Distant skin, subcutaneous, or nodal metastases | Normal |

| M1b | Lung metastases | Normal |

| M1c | All other visceral metastases | Normal |

| Any distant metastasis | Elevated | |

M, metastasis; N, node; NA, not applicable; T, tumor.

* Micrometastases are diagnosed after sentinel lymph node biopsy.

† Macrometastases are defined as clinically detectable nodal metastases confirmed pathologically.

Reprinted with permission. © 2008 American Society of Clinical Oncology. All rights reserved. Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6199-6206.

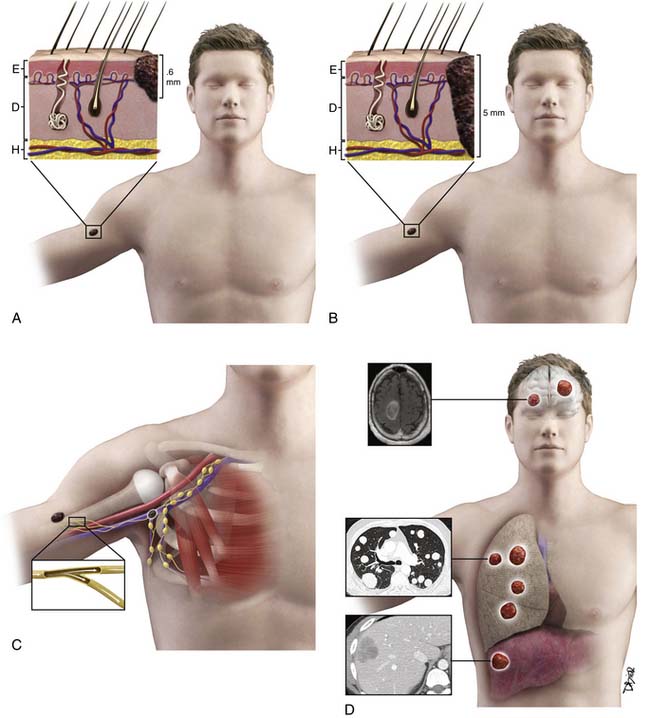

Tumor

The T category is based on primary tumor thickness, determined by measuring the maximal thickness from the top of the epidermal granular layer to the bottom of the tumor, using an ocular micrometer.28 Strata are primarily defined as T1 to T4. T1 lesions are melanomas that are 1.0 mm or less in thickness (and are also known as thin melanomas). A T2 lesion is 1.01 to 2.0 mm and a T3 lesion is 2.01 to 4.0 mm (together they compose intermediate-thickness melanoma). Melanomas greater than 4.0 mm are T4 lesions and are clinically classified as a thick melanoma. In addition to these strata, a Tx lesion is a primary tumor that cannot be assessed, such as a regressed melanoma or one associated with a curettage biopsy. T0 indicates no evidence of primary tumor and a Tis lesion indicates melanoma in situ (i.e., noninvasive melanoma). The T category is further subcategorized according to the presence or absence of primary tumor ulceration and, for T1 lesions only, the presence or absence of mitotic activity (histologically defined as mitoses/mm2).27 Primary tumor thickness at the time of diagnosis is the major determinant of prognosis and is used for treatment planning. For ulcerated lesions, primary tumor thickness is measured from the ulcer base to the bottom of the tumor. The level of invasion, originally defined by Clark, is no longer in use based on its limited independent prognostic significance in contemporary multivariate modeling.27 Instead, tumor thickness, tumor ulceration, and mitotic rate are the most powerful primary tumor prognostic factors in patients with primary melanoma. There is an inverse relationship between tumor thickness and prognosis with a significant decrease in survival with increasing tumor thickness. The same holds true for mitotic rate. Patients with an ulcerated melanoma have a lower survival rate than those patients with a nonulcerated primary lesion.27

Node

The primary criterion for the N category is defined by the number of metastatic lymph nodes present. The N category is divided into N1 to N3. The N1 category includes patients with one metastatic node. Those patients with two or three metastatic nodes are classified as N2, and those with four or more metastatic nodes or matted nodes are considered N3.

Tumor burden, the second most important prognostic factor in patients with nodal metastases, thus far has been empirically subdivided into micrometastases and macrometastases. Patients without clinical or radiologic evidence of lymph node metastases, whose regional disease was identified by sentinel node biopsy or, previously, elective lymph node dissection, are considered to have micrometastases; in contrast, those patients with clinical evidence of metastatic disease (pathologically confirmed) are classified to have macrometastases. The third and final criterion of the N category includes the presence or absence of satellites or in-transit metastases.27

Stage Groupings and Prognosis

According to the AJCC staging system, stages I and II groupings are primary melanomas without evidence of nodal or distant metastases. Stage III groupings include nodal involvement, and stage IV includes nodal and distant metastases. Current stage groupings are summarized in Table 36-2.

Among all patients with cutaneous melanoma, the prognosis is rather heterogenous. The 2009 AJCC survival rates for patients with cutaneous melanoma by stage are shown in Figure 36-4.27 For example, the 5-year survival rate is over 98% in patients with a T1a (i.e., thin) primary melanoma.27 In patients with regional lymph node metastases (i.e., stage III) the prognosis is highly variable. For example, in patients with nonulcerated primary tumors with only a single microscopically involved regional lymph node, the 5-year survival rate is approximately 80%, whereas the 5-year survival for patients with four or more clinically involved lymph nodes decreases to 25%. Overall, patients with distant metastatic melanoma (i.e., stage IV) have a poor prognosis. Patients in the AJCC M1a category have a 1-year survival rate of 62%. Patients in the AJCC category M1b have lung metastases with a 1-year survival rate of 53%. This decreases to a 33% 1-year survival rate in patients with distant metastases and an elevated serum LDH (M1c).

Key Points Staging

• Primary tumor thickness, presence of ulceration, and mitotic rate are the dominant independent predictors of survival.

• The risk of metastatic disease increases with T stage.

• Level of invasion is no longer used as a primary tumor criterion for AJCC staging.

• In patients with negative regional lymph nodes on clinical examination, intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy are used to surgically stage regional nodal basins at risk

• The primary criterion for the N category is defined by the number of metastatic regional lymph nodes. Most patients who present with regional nodal disease have evidence of microscopic nodal disease identified by lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy.

• Patients with distant metastasis are classified by site(s) of metastases (M1a, M1b, and M1c) and LDH level. Patients with an elevated LDH level have a significant reduction in survival.

Imaging

Primary Tumor

The T staging of cutaneous melanoma is based on histologic evaluation of the primary tumor. In general, there is no role of imaging in T staging of cutaneous melanoma. In rare cases, high-frequency ultrasound can be used to assess large primary tumors for which complete excision prior to treatment is not feasible, particularly when it may impact on margins of excision. Hayashi and colleagues29 studied melanomas with high-frequency (30-MHz) ultrasound. In 68 of 70 sonographically well-seen melanomas (excluding two melanoma in situ lesions), they showed good correlation between sonographic and histologic thickness (r = 0.887) and found high-frequency sonography to be quite useful in preoperative prediction of tumor thickness.29

Nodal Disease and Distant Metastatic Disease

Imaging Modalities

Lymphoscintigraphy

Regional lymph nodes are the most common first site of metastatic disease (Figure 36-5). In patients for whom sentinel node biopsy is planned, preoperative lymphoscintigraphy is generally first performed to identify site(s) of regional nodal drainage, including those patients with multiple draining nodal basins, as well as to locate unpredictable nodal basins outside the standard nodal basins and thus provides a roadmap before surgery. Preoperative intradermal injection of technetium-99m–labeled sulfur colloid and intraoperative vital blue dye (isosulfan blue 1%) is injected around the primary melanoma to assess the regional nodal basins at risk.30,31 A handheld gamma probe is used transcutaneously in the operating room to identify the sentinel lymph nodes that need to be removed. Both radiocolloid and vital blue dye mapping are complementary techniques that, when used simultaneously, increase the accuracy (>99%) of identifying the sentinel lymph nodes, opposed to using blue dye alone (84% accuracy).32

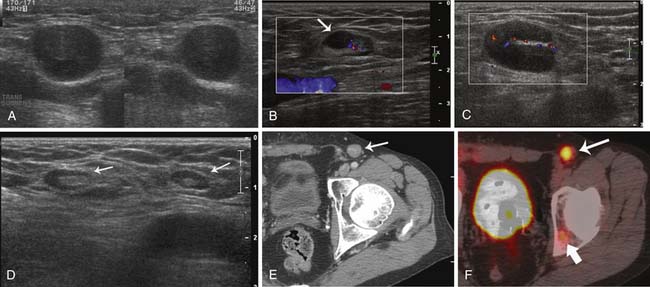

Ultrasound

Sonography is often used as the preferred modality of choice for equivocal or suspicious nodal disease on clinical examination. Indeterminate superficial lymph nodes as imaged on CT and MRI can also be further evaluated with ultrasound. The sonographic appearance of a normal lymph node is an oval-shaped node with a thin hypoechoic cortex and echogenic hilum (Figure 36-6). Metastatic disease is suspected when there is an increase in nodal size and loss of the normal ovoid morphology. Involved nodes are often hypoechoic and round with loss of their fatty hila (see Figure 36-6). Involved lymph nodes can also have preservation of the normal sonographic lymph node architecture and an enlarged cortex with a preserved hyperechoic hilum (see Figure 36-6). On some occasions, involved lymph nodes may have a prominent focal lobulation or bulge (see Figure 36-6). This is secondary to asymmetrical tumor involvement of the lymph node. These lymph nodes are amenable to ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) for pathologic confirmation. Voit and associates33 described ultrasound features of sentinel lymph node melanoma involvement. They evaluated 400 sentinel lymph nodes in patients with melanoma and concluded that ultrasound and FNA can identify 65% of all sentinel node metastases and thus reduce the need for surgical sentinel node procedures. Ultrasound characteristics of lymph nodes as described in their study include peripheral perfusion (an early sign of involvement), loss of central echoes, and a balloon-shaped lymph node (late signs of large volume disease). Sanki and coworkers,34 however, performed ultrasound on 871 sentinel lymph nodes in 716 patients with melanoma. They found a sensitivity of 24.3% for ultrasound detection of positive sentinel lymph nodes and a specificity of 96.8% and concluded that ultrasound is not an adequate substitute for sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging

There is no role for routine CT for in situ, stage I, and stage II melanoma. For patients with stage III disease and palpable nodal disease, CT may be useful in identifying other sites of metastatic disease that may preclude surgery in some patients.3 The utility of CT and MRI in patients with stage III disease and microscopic disease in sentinel lymph nodes (asymptomatic patients) is not established. However, the incidence of having distant metastases is low. CT may also be useful in patients with more advanced disease (stages IIIB, IIIC, and IV) to determine resectability and disease extent for surgical planning.3

Currently on CT and MRI, a change in nodal size is the only marker of disease. Demonstrating an increase in size of a lymph node compared with a prior examination can sometimes be an indicator of metastatic involvement. Tumor involvement may be suspected if there is a change in shape or development of heterogeneity of the lymph node. However, these characteristics are not specific and may be the result of nonmalignant etiologies such as inflammation or infection. MRI is often used as a problem-solving tool such as for the characterization of indeterminate liver lesions as imaged on CT. MRI is the modality of choice for brain metastases.

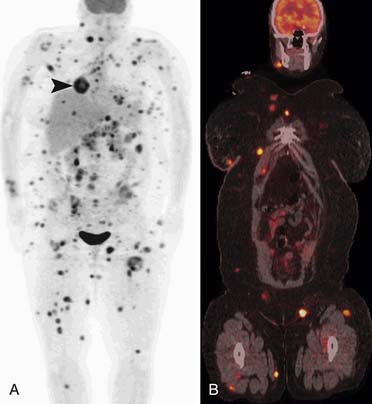

Positron-Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography

PET/CT combines functional information along with anatomic information in a single examination. The role of PET/CT in nodal disease detection is still evolving. It is important to realize that PET/CT is not specific for detection of nodal disease. Enlarged lymph nodes may demonstrate increased metabolic activity on PET/CT; however, they may simply be reactive. Conversely, normal-sized lymph nodes may contain micrometastases below the sensitivity threshold of PET/CT, demonstrating no abnormal metabolic activity. In patients with stages I and II disease, the role of PET/CT is extremely limited in the detection of microscopic nodal disease. In patients with stages III and IV disease, the role is still evolving. In patients with oligometastatic stage IV or advanced stage III disease, PET/CT may complement conventional imaging in patients in whom surgery is being contemplated. Pfannenberg and colleagues35 studied 64 patients with stage III/IV melanoma in a prospective, blinded study who underwent PET/CT and whole body MRI in which 420 lesions were evaluated. They found that such imaging was significantly more accurate in N staging and skin and subcutaneous disease detection compared with whole body MRI. However, whole body MRI was more sensitive for liver, bone, and brain metastases.35

Metastatic Sites

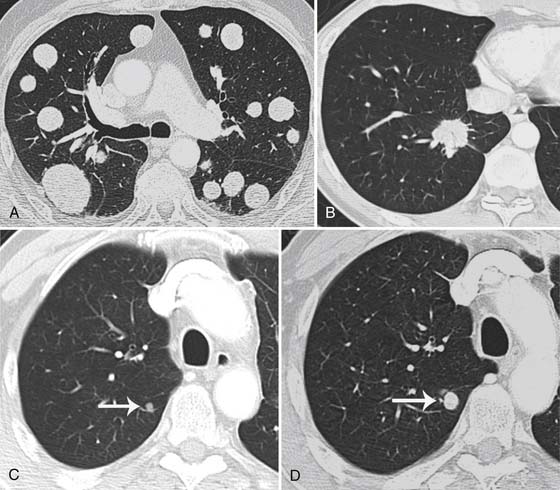

Lung

The lungs are the second most common site of metastatic disease after nodal disease.36 CT, in comparison with chest radiography, has a greater sensitivity for detection of intrathoracic metastatic disease. Pulmonary metastatic disease can present as a solitary nodule, but it is often multiple, rounded, and well-defined as seen in other cancers (Figure 36-7).37 A single nodule in a patient with melanoma is more likely to be from metastatic disease rather than a primary bronchogenic carcinoma.38,39 Primary lung cancers may be difficult to distinguish from a melanoma metastasis because some primary lung cancers can be round or oval and smoothly marginated. Some primary lung cancers, however, have spiculation of their margins (see Figure 36-7).

Skin and Soft Tissues

Cutaneous or subcutaneous metastases are best detected by clinical examination or ultrasound. They appear as hypoechoic lesions with distal acoustic enhancement, often with increased vascularity on color Doppler.40 On CT, these manifest as soft tissue density nodules, but they may be inhomogeneous secondary to necrosis. These deposits are often detected as foci of increased metabolic activity on PET/CT (Figure 36-8). However, these deposits may not demonstrate uptake if there is low-volume disease.

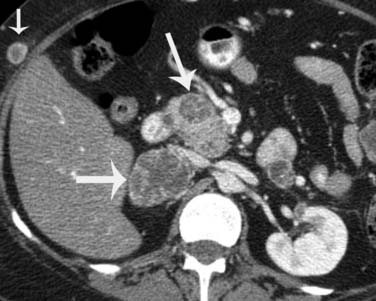

Liver

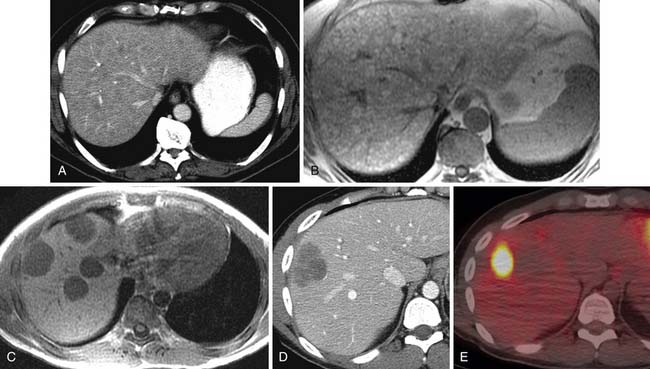

As found on autopsy series, the liver is the third most common site of metastatic melanoma.36 On CT, most melanoma metastases are low in attenuation compared with the normal liver on pre- and postintravenous contrast imaging (Figure 36-9). Abdominal MRI is performed for indeterminate lesion characterization seen on other imaging modalities including CT and ultrasound (see Figure 36-9). Metastatic melanoma liver lesions that do not have a high melanin content, the typical presentation as seen on MRI, will be hypointense on T1-weighted images. On MRI, 20% to 25% of liver lesions with high melanin content and/or hemorrhage will be hyperintense on T1-weighted images (see Figure 36-9).41 This hyperintensity can also be seen in lesions containing fat or protein. On ultrasound, melanoma liver metastases are typically hypoechoic relative to the surrounding liver. Hepatic melanoma metastases on PET/CT are fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG)–avid and appear as foci of increased metabolic activity (see Figure 36-9).

Brain

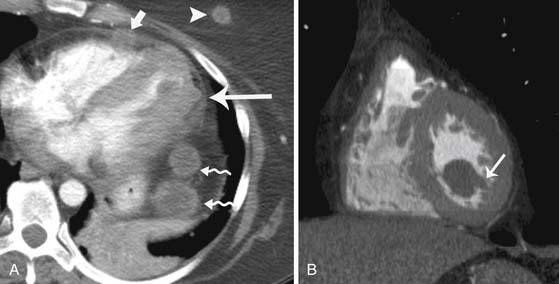

Melanoma is the third most common cause of brain metastases, following breast and lung cancer. Metastatic disease to the brain is associated with a worse prognosis compared with metastatic disease to other visceral organs and tends to occur late in the disease course. After the development of brain metastases, the median survival is 3 to 4 months.42,43 Patients with melanoma can present with acute neurologic symptoms. A nonintravenous contrast brain CT can be performed to evaluate for the cause of the acute symptoms such as stroke or hemorrhage. Brain MRI is sometimes obtained based on patient symptoms; it is also performed in patients with stage IV disease to exclude asymptomatic disease. Brain MRI may also be obtained in patients with advanced regional disease to exclude brain metastasis.

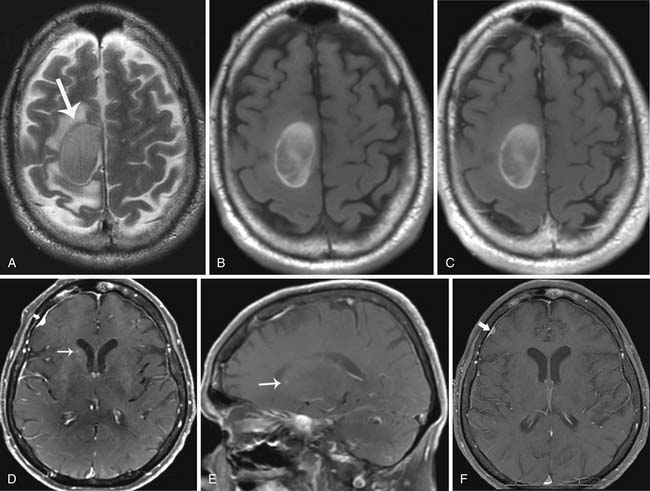

If melanoma metastases are present on CT, they are hyperdense compared with the surrounding normal brain tissue. Brain metastases, however, are best detected after the administration of intravenous contrast, with MRI being more sensitive than CT. Imaging characteristics of brain metastases from melanoma can vary. Melanin decreases T1 relaxation time on MRI. Therefore, if enough melanin is present, lesions will be hyperintense on T1-weighted MRI (Figure 36-10). T1 hyperintensity can also be secondary to hemorrhage or fat. Melanin can shorten T2* relaxation times so lesions will have decreased T2 signal intensity.44 A T1 hyperintense lesion can be due to melanin, hemorrhage, or both.45–48 An amelanotic pattern in which metastases contain less than 10% melanin-containing cells can also be seen and associated with a signal intensity pattern that is seen in metastases from other primary tumors. Such lesions will generally be isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted images and isointense or hyperintense on T2-weighted images (see Figure 36-10).46

Metastatic disease to the gray-white matter junction is most common and can be solitary but is often multiple.49 Miliary and subependymal metastases are also seen.44 Melanoma metastases can often present as punctuate or subtle lesions, often mistaken for normal blood vessels; owing to the rapid growth of metastatic disease, close follow-up imaging is needed (see Figure 36-10).

Head and Neck

Melanoma may metastasize not only to the brain parenchyma but also other intra- and extracranial structures including bone, muscle, skin, nasopharynx and mucosa, parotid gland, meninges, choroid plexus, perineural spread, the internal auditory canal, and the orbit.44 Leptomeningeal disease detection can be problematic because repeat lumbar punctures for cerebrospinal fluid testing may be inaccurate in 15% to 20% of cases.50 MRI with intravenous contrast may be helpful in leptomeningeal disease detection, in which radiologic signs include leptomeningeal, dural, and cranial nerve enhancement; superficial cerebral metastasis; hydrocephalus; subependymal enhancement; and/or enhancement of subarachnoid nodules.51 False-positive leptomeningeal enhancement, however, can be seen with hemorrhage and inflammation due to infection or intrathecal chemotherapy.51,52

Metastatic disease to the thyroid gland is not common, but it can be seen in patients with various primary cancers including renal, breast, lung, colon, or prostate cancer or melanoma.53

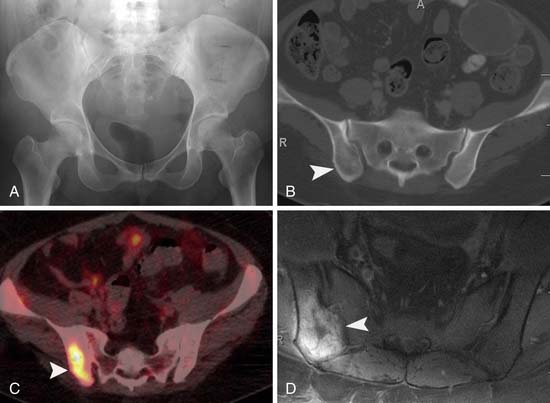

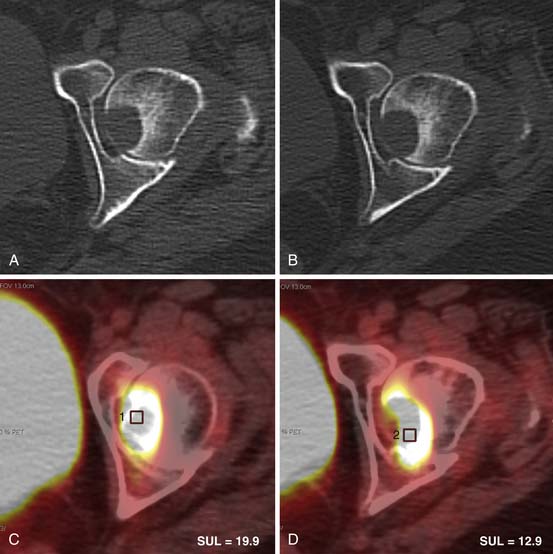

Musculoskeletal System

Potepan and associates54 reviewed 120 melanoma bone metastases and found that most metastases are osteolytic (87.5%). The second most common pattern was a mixed osteolytic-osteoblastic pattern found in 10% of cases, and a pure osteoblastic pattern was seen in 2.5% of cases. Heusner and coworkers55 studied 54 patients with non–small cell lung cancer and 55 patients with melanoma who underwent PET/CT as well as whole body MRI. Of these 109 patients, 11 patients had bone metastases (8 patients with non–small cell lung cancer and 3 patients with melanoma). They found that PET/CT and MRI were equal in detection of skeletal metastases in both these patient populations (Figure 36-11). Bone scintigraphy may be negative owing to lack of bone reaction from metastases to the bone marrow.56 Gokaslan and colleagues57 studied 133 patients with melanoma metastases to the spine. Bone scan was performed in 85 of these patients with a 15% false-negative rate compared with plain films, CT, or MRI.

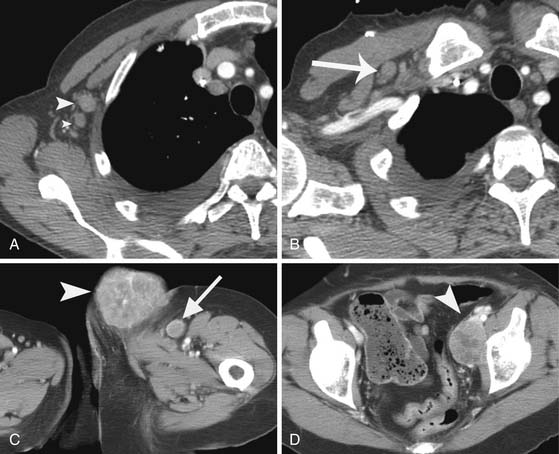

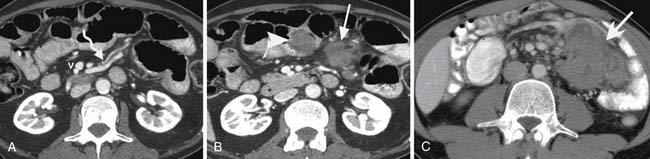

Gastrointestinal Tract

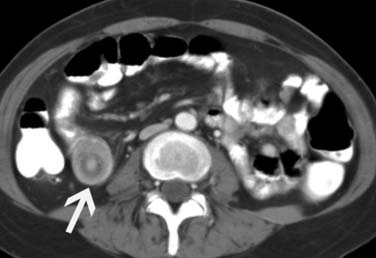

The most frequently involved sites in the gastrointestinal tract are the small and large bowel (75% and 25%, respectively).8 Disease can vary in size and present as single or multiple nodules, but can also be irregular or polypoid or have an infiltrating appearance.8 Complications of small bowel metastases include intussusception, small bowel obstruction, and perforation (Figure 36-12).

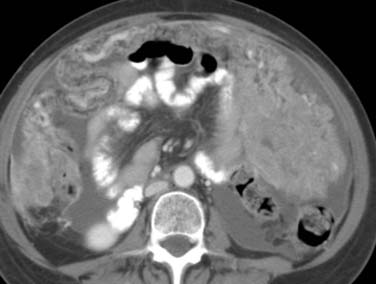

Genitourinary Tract

Metastatic disease to the adrenal gland is nonspecific and has imaging characteristics similar to other cancers that metastasize to them. They can present as lobulated, heterogeneously enhancing soft tissue masses and typically metastasize unilaterally (Figure 36-13); however, they can be bilateral in some patients.58

Melanoma metastases to the kidney may be solid or cystic. Disease can also present as perirenal solid nodules.8 Urothelial metastases is less common but, when they occur, can appear as an intraluminal filling defect on the excretory phase as seen in transitional cell cancers. Metastases to the urinary bladder can also be similar to transitional cell carcinomas presenting as a soft tissue mass involving the urinary bladder wall.

Metastatic disease to the ovaries can present as solid or solid/cystic masses. Metastasis from melanoma to the uterus or cervix is also rare. In an analysis of 63 cases of metastatic cancers to the uterine corpus from extragenital neoplasms, the most common extragenital neoplasm to metastasize to the uterine corpus was found to be from breast cancer.59

Gallbladder, Pancreas, and Spleen

Metastatic disease to the pancreas and spleen is rare. The incidence of melanoma metastasis to the spleen is less than 5%.60,61 Both splenic and pancreatic metastases can vary in size and number and may be solid or cystic (see Figure 36-13). Metastatic disease to the pancreas may present as a hypervascular solid mass, similar to metastases from renal cell carcinoma or primary pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors.

Mesentery

Melanoma involving the small or large bowel mesenteries can manifest as single or multiple nodules or have an infiltrative appearance that is confluent insinuating into surrounding tissues, a similar finding seen in lymphoma, carcinoid, or desmoid tumors (Figure 36-14).8,62 Detection of jejunal small bowel adenopathy can be found by locating the superior mesenteric vein and tracing the jejunal veins to the left side of the abdomen into the jejunal small bowel mesentery. Although uncommon, disease manifestation as seen in ovarian cancer can also occur in patients with melanoma including peritoneal nodules or carcinomatosis (Figure 36-15).

Thorax

Melanoma can metastasize to rare sites in the thorax including the pleura, bronchi, breast, heart, and pericardium. Melanoma metastases have a propensity to metastasize to the myocardium (Figure 36-16).63

Key Points Imaging

• The radiology report should include all sites of metastatic disease with a thorough search of all organ systems including subcutaneous tissues and muscle.

• In patients undergoing sentinel node biopsy, preoperative lymphoscintigraphy is generally first performed to identify site(s) of regional nodal drainage, including those patients with multiple draining nodal basins, as well as to locate unpredictable nodal basins outside the standard nodal basins.

• Recognition of vertebral metastases causing spinal cord compression and neurologic compromise is important for possible radiotherapy.

Treatment*

Surgery

Surgical resection of the primary tumor is performed by wide local excision and represents the mainstay of treatment for early-stage disease. The recommended margin of excision is based on the tumor thickness of the primary tumor, with recommendations of 1 or 2 cm based on tumor thickness. Patient-specific surgical planning may vary, however, based on anatomic constraints associated with the location of the primary tumor. For example, facial lesions cannot often be excised with more than a 1-cm margin owing to the proximity of nearby vital structures.64 The technique of intraoperative lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy is generally offered to patients with primary cutaneous melanoma who have intermediate- to high-risk occult regional nodal disease in an effort to identify microscopic nodal disease by accurate pathologic regional lymph node staging and to patients who have occult disease for regional disease control and potential cure.64 Regional lymph node metastases are generally treated by lymphadenectomy.

Surgery is also often considered as a component of the treatment plan for satellite and in-transit disease, particularly when solitary or confined. Hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion or, more recently, minimally invasive isolated limb infusion—both relatively specialized techniques involving regional administration of cytotoxic agents (most commonly melphalan) to the involved extremity—is also employed for the management of in-transit disease.

Nonsurgical Therapy

Adjuvant Therapy

The risk of recurrence in patients with thick primary melanomas or positive lymph nodes can be significant; therefore, adjuvant therapies have been used in an attempt to minimize disease recurrence. Interferon-alpha (IFN-α) is a natural protein produced by immune cells in response to pathogens by stimulating a T-cell response. IFN-α has been shown to have an impact on disease-free survival in the adjuvant setting for stage III melanoma.64

Melanoma cells express various antigens that are recognized by T cells. Some included antigens expressed by melanocytes and melanoma cells (e.g., MART-1, gp100), cancer-testis antigens (MAGE-1), and mutated antigens (e.g., beta-catenin).65 It is thought that using vaccine therapy will prevent recurrent disease in patients with metastatic melanoma. With the administration of multiple immunizations, activation of antigen-specific immune cells can be achieved.64 This form of treatment approach currently remains in the clinical research environment.

Chemotherapy

Dacarbazine (DTIC) is the standard chemotherapy used in the treatment of metastatic melanoma. Temozolomide, an oral congener of dacarbazine, is also used for treatment of metastatic disease. Combination chemotherapeutic regimens including cisplatin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine (CVD) or carboplatin and taxol in some series have shown higher response rates but no survival advantages compared with single-agent DTIC.66–68

Cytokine Therapy

Melanoma antigens are recognized by cytotoxic T cells. Interleukin-2 (IL-2) is a protein produced by T cells. Infusion of IL-2 stimulates the immune response and has been shown to induce responses in some patients.64 In patients with cutaneous or subcutaneous metastases and no visceral metastases, response rates have been seen as high as 50%, and therefore, high-dose IL-2 may be used as a first-line agent in some patients.69

Biochemotherapy

Biochemotherapy is the combination of both chemotherapy and cytokine therapy and has been used in some patients with aggressive locoregional disease. CVD in conjunction with IL-2 and IFN-α has been used as a biochemotherapy treatment regimen. The majority of studies have shown no difference in overall survival of patients treated with biochemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone. Bedikian and associates,70,71 however, studied patients with metastatic melanoma treated with biochemotherapy and reported a 10-year survival of 12.5%.

Adoptive T-Cell Therapy

Adoptive T-cell therapy is the practice of infusion of autologous antigen-specific T cells that have been isolated from tumors harvested from individual patients that have been expanded in culture in the laboratory. This approach has been used to treat a variety of diseases, including melanoma, with the most success seen with treatment with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). In some patients, tumor-specific T cells can be cultured from the patient’s tumor and reinfused back into the patient.64 Clinical trials employing this promising, albeit labor-intensive, approach are under way.

Radiation Therapy

Even though surgery is the mainstay of treatment for localized or regional metastatic melanoma, radiation therapy may be used for locoregional disease control in patients with high-risk features or when complete surgical resection cannot be performed. In some patients, radiation therapy can be used for long-term control and palliation. Sites of disease for which radiotherapy may be offered include osseous metastases or other sites not amenable to surgery, such as fungating or bleeding cutaneous metastases or bleeding from visceral sites. Radiotherapy is often used for treatment of vertebral metastases causing spinal cord compression and neurologic compromise.72 Stereotactic radiosurgery is also used for brain metastasis.

Key Points Treatment

• Surgical resection of the primary tumor is performed by wide local excision and is the mainstay of treatment for early-stage melanoma.

• Sentinel lymph node biopsy is generally offered to patients with primary cutaneous melanoma who have intermediate- to high-risk primary cutaneous melanoma in an effort to identify occult microscopic regional nodal disease.

• Regional disease is usually treated by lymphadenectomy.

• Surgery may be performed in patients with distant metastases for palliation for isolated or oligometastatic disease.

• Biochemotherapy is the combination of both chemotherapy and cytokine therapy and has been used in patients with aggressive locoregional or distant metastases.

• Radiotherapy is often used for treatment of metastases causing spinal cord compression, brain metastasis, or bone metastasis.

Surveillance

The utility of imaging examinations in patients with cutaneous melanoma is dependent on the melanoma stage (i.e., based on primary tumor evaluation and the presence or absence of nodal and/or metastatic disease).3 For routine surveillance, as per the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, imaging studies are not indicated for early-stage disease (stages 0-IA). For these patients, an annual skin examination and patient education of monthly skin self-examination are recommended.1 For stages IB to IV disease, in addition to annual skin examination and monthly skin self-examination, a history and physical examination focusing on nodes and skin should be performed every 3 to 6 months for 2 years, then every 3 to 12 months for 2 years, and then annually as indicated. Laboratory studies including LDH and complete blood count can be performed every 6 to 12 months. A chest radiograph can be performed for comparison with baseline studies; however, routine imaging is not recommended for stages IB and IIA. CT can be performed based on clinical signs or patient symptoms for stages IIB and higher for recurrent or metastatic disease assessment. Other modalities such as ultrasound, PET/CT, or MRI also may be indicated depending on signs or symptoms.1

Monitoring Tumor Response

Monitoring tumor response is based on decrease in size or resolution of solid organ metastases or decrease in size of nodal metastases as detected on CT or MRI using RECIST (Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors).73 For example, tumor burden for response determination is assessed by measuring the longest diameter of five lesions in the axial plane (two per organ). Lymph nodes that are 15 mm or larger in short axis are considered pathologic, and when they decrease to 10 mm or less, they are considered normal. However, these measurements are not specific for tumor involvement (because lymph nodes may enlarge secondary to infection or inflammation or metastastic lymph nodes may be < 10 mm) and have been chosen for reasons of simplicity.73 PET/CT may show improvement in disease by demonstrating decreased metabolic activity. However, there is insufficient standardization of PET/CT, a functional imaging modality, to substitute anatomic assessment described in RECIST. Further prospective clinical trials and meta-analyses are warranted in this regard.74

Detection of Recurrence

Locoregional recurrence is often found by patient self-examination or by physical examination. Ultrasound may be used to evaluate surgical resection scars or regional lymph node basins at risk for metastatic disease. FNA can be performed for local scar recurrence as well as for local satellitosis and/or in-transit recurrence. A study by Voit and coworkers75 compared the efficacy of ultrasound versus physical examination for evaluating tumor recurrence and found that ultrasound was more sensitive than physical examination.

Guidelines have been provided by the NCCN for approaches to management of patients with melanoma. It is important to note that these guidelines are a consensus of authors’ views of approaches to diagnosis, workup, and treatment. For nodal recurrence, FNA or lymph node biopsy is performed. Imaging studies such as CT, PET/CT, or MRI can be performed. For example, a pelvic CT can be performed for clinically positive inguinofemoral adenopathy.1

For distant metastatic disease, FNA or biopsy can be performed as well as chest x-ray or chest CT in addition to abdominal and pelvic CT and brain MRI or PET/CT as indicated. PET/CT may be useful to characterize lesions that are indeterminate on CT as well as image areas (arms and legs) not scanned on routine CT scanning.1

PET/CT has an extremely limited role in detecting subclinical nodal disease or distant metastases in patients with early-stage disease and is rarely recommended for staging or surveillance in this group in the absence of specific complaints for which imaging may be important for clinical assessment. PET/CT, however, may have an important role in assessing patients with advanced regional disease or oligometastatic distant disease, particularly when surgery is contemplated.3 PET/CT can be useful for evaluating resectability and to identify stage IV disease, which may preclude surgery. It can also be used in patients with equivocal findings on other imaging such as CT or MRI. False negatives, however, can occur if there is small-volume disease in which the tumor burden is below the detection of PET/CT. Conversely, false-positive disease can occur in which metabolic activity may be due to inflammation, infection, postsurgical change, brown fat, or exercised muscle. This can lead to misinterpretation of metastatic disease, which may require additional imaging or biopsy for further evaluation.

Complications of Therapy

Possible complications of lymphadenectomy include lymphedema, pain, numbness, and decreased range of motion. Possible complications with isolated limb infusion include myonecrosis, nerve injury, compartment syndrome, and arterial thrombosis. In severe cases (rare), fasciotomy or amputation may be necessary.64

Side effects of temozolomide include nausea, vomiting, headache, constipation, and myelosuppression. Complications of IL-2 therapy include hypotension, capillary leak syndrome, which can lead to pulmonary edema, and renal toxicity.64 The side effects of IFN-α include fever, fatigue, depression, and liver toxicity. For this reason, liver function tests are monitored.

Key Points Detection of recurrence and complications

• Imaging studies are not indicated for early-stage disease (stages 0-IA).

• Ultrasound can be used in evaluating surgical resection scars or regional lymph node basins at risk for metastatic disease.

• PET/CT has an extremely limited role in detecting subclinical nodal disease or distant metastases in patients with early-stage disease and is rarely recommended for staging or surveillance in this group in the absence of specific complaints.

• PET/CT can be useful for evaluating resectability and to identify stage IV disease, which may preclude surgery

• Monitoring tumor response is based on decrease in size or resolution of solid organ metastases or decrease in size of nodal metastases as detected on CT or MRI using RECIST

• No available biologic markers are available to detect the presence of melanoma metastases or gauge treatment response.

• Complications of IL-2 therapy include hypotension, capillary leak syndrome, which can lead to pulmonary edema, and renal toxicity.

• Complications of lymphadenectomy include lymphedema, pain, numbness, and decreased range of motion.

New Therapies

Anti-CTLA-4

Anti-CTLA-4 therapy has been studied in trials in patients with advanced metastatic melanoma.64 CTLA-4 is a molecule expressed on T cells after activation and strongly binds to co-stimulatory molecules on antigen-presenting cells that prevent binding of these molecules needed for T-cell activation. The CTLA-4 molecule acts as a halting mechanism, decreasing the function of T cells. Antibodies that block CTLA-4, therefore, release this halting mechanism and increase the activation of T cells. Long-term disease-free survival has been seen in some patients receiving this therapy.64

PLX4032 (Vemurafenib)

V600E BRAF is the most common kinase mutation and may be identified in over 60% of patients with cutaneous melanoma. Most of the transforming activity of BRAF V600E is via activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway.76 PLX4032 (vemurafenib) is an oral inhibitor of the V600E mutant BRAF kinase. Phase I studies by Flaherty and Smalley77 have shown that PLX4032 demonstrates antitumor activity in V600E BRAF tumors. PLX4032 (vemurafenib) has shown encouraging responses in phase I/II trials. In a Phase III randomized clinical trial comparing vemurafenib versus dacarbazine in 675 patients with the BRAF V600E mutation with untreated metastatic melanoma, vemurafenib was found to show improved rates of overall and progression-free survival.78,79

1. Coit D.G., Andtbacka R., Bichakjian C.K., et al. Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7:250-275.

2. Gershenwald J.E., Thompson W., Mansfield P.F., et al. Multi-institutional melanoma lymphatic mapping experience: the prognostic value of sentinel lymph node status in 612 stage I or II melanoma patients. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:976-983.

3. Choi E.A., Gershenwald J.E. Imaging studies in patients with melanoma. Surg Oncol Clin North Am.. 2007;16:403-430.

4. Siegel R., Ward E., Brawley O., et al. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:212-236.

5. Ries L.A.G., Melber D., Krapcho M. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2005. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2008.

6. Cancer Research UK. Skin cancer—UK incidence statistics. Cancer Research UK. 2009. Available at http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerstats/types/skin/incidence/index.htm

7. Tucker M.A. Melanoma epidemiology. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am.. 2009;23:383-395. vii

8. Kamel I.R., Kruskal J.B., Gramm H.F. Imaging of abdominal manifestations of melanoma. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1998;39:447-486.

9. DeMatos P., Wolfe W.G., Shea C.R., et al. Primary malignant melanoma of the esophagus. J Surg Oncol. 1997;66:201-206.

10. Ost D., Joseph C., Sogoloff H., Menezes G. Primary pulmonary melanoma: case report and literature review. Mayo Clin Proc.. 1999;74:62-66.

11. Sanchez A.A., Wu T.T., Prieto V.G., et al. Comparison of primary and metastatic malignant melanoma of the esophagus: clinicopathologic review of 10 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2008;132:1623-1629.

12. Prieto V.G., Shea C.R. Use of immunohistochemistry in melanocytic lesions. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(Suppl 2):1-10.

13. Rigel D.S., Friedman R.J., Kopf A.W., Polsky D. ABCDE—an evolving concept in the early detection of melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1032-1034.

14. Pawlik T.M., Ross M.I., Johnson M.M., et al. Predictors and natural history of in-transit melanoma after sentinel lymphadenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:587-596.

15. Uren R.F., Howman-Giles R., Thompson J.F., et al. Interval nodes: the forgotten sentinel nodes in patients with melanoma. Arch Surg. 2000;135:1168-1172.

16. Thompson J.F., Hunt J.A., Culjak G., et al. Popliteal lymph node metastasis from primary cutaneous melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2000;26:172-176.

17. Uren R.F., Howman-Giles R., Thompson J.F. Patterns of lymphatic drainage from the skin in patients with melanoma. J Nucl Med. 2003;44:570-582.

18. Kang J.C., Wanek L.A., Essner R., et al. Sentinel lymphadenectomy does not increase the incidence of in-transit metastases in primary melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4764-4770.

19. Morton D.L., Thompson J.F., Cochran A.J., et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1307-1317.

20. Pawlik T.M., Ross M.I., Thompson J.F., et al. The risk of in-transit melanoma metastasis depends on tumor biology and not the surgical approach to regional lymph nodes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4588-4590.

21. van Poll D., Thompson J.F., Colman M.H., et al. A sentinel node biopsy does not increase the incidence of in-transit metastasis in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:597-608.

22. Bakalian S., Marshall J.C., Logan P., et al. Molecular pathways mediating liver metastasis in patients with uveal melanoma. Clin Cancer Res.. 2008;14:951-956.

23. Kath R., Hayungs J., Bornfeld N., et al. Prognosis and treatment of disseminated uveal melanoma. Cancer. 1993;72:2219-2223.

24. Lorigan J.G., Wallace S., Mavligit G.M. The prevalence and location of metastases from ocular melanoma: imaging study in 110 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:1279-1281.

25. Rajpal S., Moore R., Karakousis C.P. Survival in metastatic ocular melanoma. Cancer. 1983;52:334-336.

26. Peruzzi B., Bottaro D.P. Targeting the c-Met signaling pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res.. 2006;12:3657-3660.

27. Balch C.M., Gershenwald J.E., Soong S.J., et al. Melanoma of the skin. In: Edge S.E., Byrd D.R., Compton C.A., et al. AJCC Staging Manual. New York: Springer, 2009. :325-344

28. Breslow A. Tumor thickness, level of invasion and node dissection in stage I cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg. 1975;182:572-575.

29. Hayashi K., Koga H., Uhara H., Saida T. High-frequency 30-MHz sonography in preoperative assessment of tumor thickness of primary melanoma: usefulness in determination of surgical margin and indication for sentinel lymph node biopsy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:426-430.

30. Gershenwald J.E., Balch C.M., Soong S., Thompson J.F. Prognostic factors and natural history of melanoma. In: Balch C.M., Houghton A.N., Sober A.J., et al. Cutaneous melanoma. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2009:35-64.

31. Gershenwald J.E., Thompson J.F., Mozzilo N., Balch C.M. Intraoperative mapping and sentinel node technology in patients with melanoma. In: Balch C.M., Houghton A.N., Sober A.J., et al. Cutaneous melanoma. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2009:415-446.

32. Gershenwald J.E., Tseng C.H., Thompson W., et al. Improved sentinel lymph node localization in patients with primary melanoma with the use of radiolabeled colloid. Surgery. 1998;124:203-210.

33. Voit C., Van Akkooi A.C., Schafer-Hesterberg G., et al. Ultrasound morphology criteria predict metastatic disease of the sentinel nodes in patients with melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:847-852.

34. Sanki A., Uren R.F., Moncrieff M., et al. Targeted high-resolution ultrasound is not an effective substitute for sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5614-5619.

35. Pfannenberg C., Aschoff P., Schanz S., et al. Prospective comparison of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography and whole-body magnetic resonance imaging in staging of advanced malignant melanoma. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43:557-564.

36. Patel J.K., Didolkar M.S., Pickren J.W., Moore R.H. Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma. A study of 216 autopsy cases. Am J Surg. 1978;135:807-810.

37. Fishman E.K., Kuhlman J.E., Schuchter L.M., et al. CT of malignant melanoma in the chest, abdomen, and musculoskeletal system. Radiographics. 1990;10:603-620.

38. Krug B., Dietlein M., Groth W., et al. Fluor-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) in malignant melanoma. Diagnostic comparison with conventional imaging methods. Acta Radiol. 2000;41:446-452.

39. Quint L.E., Park C.H., Iannettoni M.D. Solitary pulmonary nodules in patients with extrapulmonary neoplasms. Radiology. 2000;217:257-261.

40. Nazarian L.N., Alexander A.A., Kurtz A.B., et al. Superficial melanoma metastases: appearances on gray-scale and color Doppler sonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170:459-463.

41. Burkill G J.C., King D.M. Malignant tumours of the skin. In: Husband J.E., Reznek R.H. Imaging in Oncology. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2004:1149-1168.

42. Sampson J.H., Carter J.H.Jr., Friedman A.H., Seigler H.F. Demographics, prognosis, and therapy in 702 patients with brain metastases from malignant melanoma. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:11-20.

43. Walbert T., Gilbert M.R. The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of patients with brain metastases from solid tumors. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14:299-306.

44. Escott E.J. A variety of appearances of malignant melanoma in the head: a review. Radiographics. 2001;21:625-639.

45. Hammersmith S.M., Terk M.R., Jeffrey P.B., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of nasopharyngeal and paranasal sinus melanoma. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:245-253.

46. Isiklar I., Leeds N.E., Fuller G.N., Kumar A.J. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;165:1503-1512.

47. Marx H.F., Colletti P.M., Raval J.K., et al. Magnetic resonance imaging features in melanoma. Magn Reson Imaging. 1990;8:223-229.

48. Woodruff W.W.Jr., Djang W.T., McLendon R.E., et al. Intracerebral malignant melanoma: high-field-strength MR imaging. Radiology. 1987;165:209-213.

49. Osborn A.G. Part III, brain tumors and tumorlike processes. In: Patterson A.S., editor. Diagnostic Neuroradiology. St. Louis: Mosby; 1994:656-670.

50. Glass J.P., Melamed M., Chernik N.L., Posner J.B. Malignant cells in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF): the meaning of a positive CSF cytology. Neurology. 1979;29:1369-1375.

51. Freilich R.J., Krol G., DeAngelis L.M. Neuroimaging and cerebrospinal fluid cytology in the diagnosis of leptomeningeal metastasis. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:51-57.

52. Paakko E., Patronas N.J., Schellinger D. Meningeal Gd-DTPA enhancement in patients with malignancies. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1990;14:542-546.

53. Yeung M.J., Serpell J.W. Management of the solitary thyroid nodule. Oncologist. 2008;13:105-112.

54. Potepan P., Spagnoli I., Danesini G.M., et al. The radiodiagnosis of bone metastases from melanoma [in Italian]. Radiol Med. 1994;87:741-746.

55. Heusner T., Golitz P., Hamami M., et al. “One-stop-shop” staging: should we prefer FDG-PET/CT or MRI for the detection of bone metastases? Eur J Radiol. 2011;78:430-435.

56. Aydin A., Yu J.Q., Zhuang H., Alavi A. Detection of bone marrow metastases by FDG-PET and missed by bone scintigraphy in widespread melanoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2005;30:606-607.

57. Gokaslan Z.L., Aladag M.A., Ellerhorst J.A. Melanoma metastatic to the spine: a review of 133 cases. Melanoma Res.. 2000;10:78-80.

58. King D.M. Imaging of metastatic melanoma. Cancer Imaging. 2006;6:204-208.

59. Kumar N.B., Hart W.R. Metastases to the uterine corpus from extragenital cancers. A clinicopathologic study of 63 cases. Cancer. 1982;50:2163-2169.

60. Shirkhoda A., Albin J. Malignant melanoma: correlating abdominal and pelvic CT with clinical staging. Radiology. 1987;165:75-78.

61. Silverman P.M., Heaston D.K., Korobkin M., Seigler H.F. Computed tomography in the detection of abdominal metastases from malignant melanoma. Invest Radiol. 1984;19:309-312.

62. Sheth S., Horton K.M., Garland M.R., Fishman E.K. Mesenteric neoplasms: CT appearances of primary and secondary tumors and differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2003;23:457-473. quiz 535–546

63. Gibbs P., Cebon J.S., Calafiore P., Robinson W.A. Cardiac metastases from malignant melanoma. Cancer. 1999;85:78-84.

64. Gershenwald J.E., Hwu P.. Melanoma. Hong W.K., Bast J., R C., Hait W.N., et al. Cancer Medicine. 8th ed. Shelton, CT: People’s Medical Publishing House. 2010:1459-1486.

65. Wang R.F., Rosenberg S.A. Human tumor antigens for cancer vaccine development. Immunol Rev. 1999;170:85-100.

66. Chapman P.B., Einhorn L.H., Meyers M.L., et al. Phase III multicenter randomized trial of the Dartmouth regimen versus dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2745-2751.

67. Luikart S.D., Kennealey G.T., Kirkwood J.M. Randomized phase III trial of vinblastine, bleomycin, and cis-dichlorodiamine-platinum versus dacarbazine in malignant melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 1984;2:164-168.

68. Rusthoven J.J., Quirt I.C., Iscoe N.A., et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial comparing the response rates of carmustine, dacarbazine, and cisplatin with and without tamoxifen in patients with metastatic melanoma. National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:2083-2090.

69. Chang E., Rosenberg S.A. Patients with melanoma metastases at cutaneous and subcutaneous sites are highly susceptible to interleukin-2-based therapy. J Immunother. 2001;24:88-90.

70. Bedikian A.Y., Johnson M.M., Warneke C.L., et al. Systemic therapy for unresectable metastatic melanoma: impact of biochemotherapy on long-term survival. J Immunotoxicol. 2008;5:201-207.

71. Bedikian A.Y., Johnson M.M., Warneke C.L., et al. Prognostic factors that determine the long-term survival of patients with unresectable metastatic melanoma. Cancer Invest. 2008;26:624-633.

72. Ballo M.T., Ang K.K. Radiation therapy for malignant melanoma. Surg Clin North Am.. 2003;83:323-342.

73. Eisenhauer E.A., Therasse P., Bogaerts J., et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228-247.

74. Sargent D.J., Rubinstein L., Schwartz L., et al. Validation of novel imaging methodologies for use as cancer clinical trial end-points. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:290-299.

75. Voit C., Mayer T., Kron M., et al. Efficacy of ultrasound B-scan compared with physical examination in follow-up of melanoma patients. Cancer. 2001;91:2409-2416.

76. Smalley K.S., Flaherty K.T. Integrating BRAF/MEK inhibitors into combination therapy for melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:431-435.

77. Flaherty K.T., Smalley K.S. Preclinical and clinical development of targeted therapy in melanoma: attention to schedule. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res.. 2009;22:529-531.

78. Halaban R., Zhang W., Bacchiocchi A., et al. PLX4032, a selective BRAF(V600E) kinase inhibitor, activates the ERK pathway and enhances cell migration and proliferation of BRAF(WT) melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2010;23:190-200.

79. P.B. Chapman, A.. Hauschild, C.. Robert. Improved survival with vemurafenib in melanoma with BRAF V600E. N Engl J Med... 2011;364:2507-2516.