Meibomian Gland Disease

Treatment

Introduction

Meibomian gland disease is one of the most commonly encountered clinical problems and can occur as focal or diffuse involvement of the meibomian glands. Meibomian glands are anatomically located in the tarsal plate of both upper and lower eyelids, as holocrine sebaceous glands that open directly on the eyelid margin and discharge their entire contents onto the lid margin. A full description of the anatomy and physiology of the glands is provided in the Report of the Meibomian Gland Workshop published in 2011.1 The meibomian gland is a type of sebaceous gland and it is susceptible to disease entities that affect all sebaceous glands, such as seborrhea and rosacea.1 Since obstruction of the gland orifice and alteration of the meibomian secretion are the predominant pathophysiological causes of disease, management of the clinical problem centers around relief of obstruction and modification of the abnormal secretion, as well as control of inflammation when it occurs as part of the disease process.

Classification of Meibomian Gland Disease

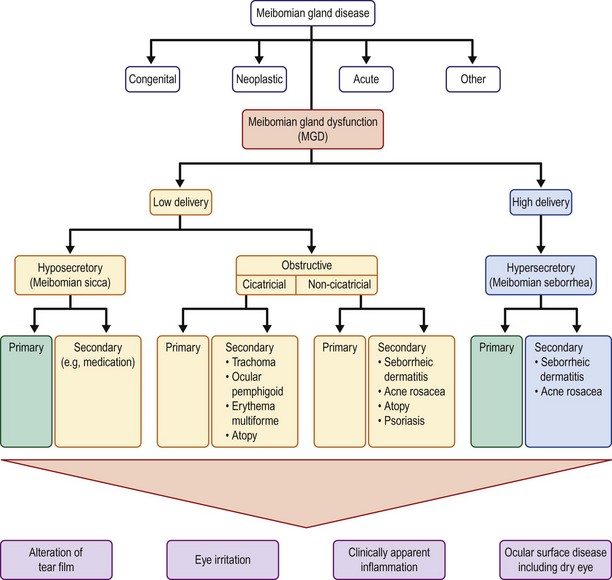

The etiology of meibomian gland disease can be congenital or acquired. A classification system proposed by the International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction is depicted in Figure 10.1.2 Congenital absence of the meibomian gland occurs and is particularly severe in association with anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia.3

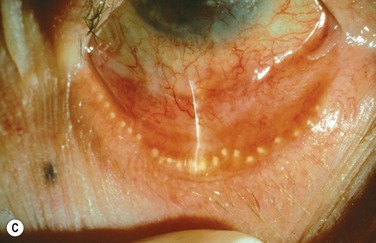

Acquired disease occurs as both focal (internal hordeolum or chalazion) or diffuse (meibomian gland dysfunction: MGD) involvement. Although obstruction of the glandular orifice is the likely first event, the clinical appearance is very different, as the internal hordeolum (Fig. 10.2) is the result of an acute bacterial infectious inflammation, while chalazion (Fig. 10.3) is the result of a chronic localized lipogranulomatous inflammation, and meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) (Figs 10.4 and 10.5) is primarily obstructive with variable inflammatory reaction and typically no active infectious component, although lid margin flora may influence metabolism of the meibum secretion.4 Thus, the management of the various clinical manifestations of meibomian gland disease differs in both the pathophysiological target and recommended therapy.

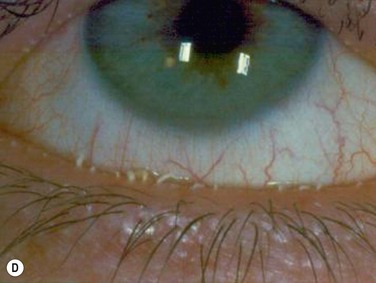

Figure 10.4 (A) MGD with epithelial obstruction of meibomian gland orifice. (B) MGD with meibomian gland secretion turbidity. (Reproduced with permission of Elsevier. From Foulks GN, Bron AJ. Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. A Clinical Scheme for Description, Diagnosis, Classification, and Grading. The Ocular Surface 2003;1:107–26.) (C) MGD with meibomian gland secretion that is turbid with clumps. (D) MGD with meibomian gland secretion that is paste consistency.

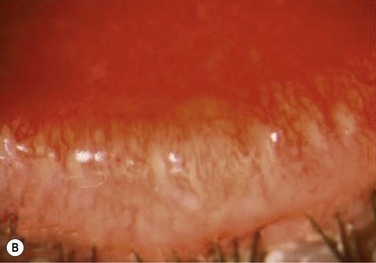

Figure 10.5 (A) Chronic MGD change of telangiectasia of eyelid margin. (B) Chronic MGD with cicatricial obstruction of meibomian gland orifice. (Reproduced with permission of Elsevier. From Foulks GN, Bron AJ. Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. A Clinical Scheme for Description, Diagnosis, Classification, and Grading. The Ocular Surface 2003;1:107–26.) (C) Chronic MGD with posterior traction of meibomian gland orifice due to cicatricial change. (Reproduced with permission of Elsevier. From Foulks GN, Bron AJ. Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. A Clinical Scheme for Description, Diagnosis, Classification and Grading. The Ocular Surface 2003;1:107–26.)

Pathophysiological Targets and Goals of Therapy

Since internal hordeolum is acute suppurative inflammation of the meibomian gland, antibiotic therapy of the infectious component and anti-inflammatory therapy to control the acute inflammation are both appropriate treatments. Relief of obstruction of the gland is also important. The infecting organism is most often Staphylococcus but other bacteria can be present.5 No good comparative clinical trials have been published to compare effectiveness of treatment options for internal hordeolum,6 but the use of topical antibiotic drops or ointments includes topical erythromycin, bacitracin, tobramycin, or fluoroquinolones. In adults with severe or recurrent disease, oral doxycycline can be prescribed as systemic therapy. Application of warm compresses periodically during the day helps to reduce inflammation and encourages the infection to localize to a point which may spontaneously erupt to relieve the obstruction. Occasionally, surgical lancing of the pointing hordeolum speeds resolution. Anti-inflammatory therapy with topical corticosteroid can be helpful when inflammation is severe.

Since chalazion is a chronic focal reaction of the tissue to altered lipid components of meibum occurring in an obstructed gland, the primary therapy is first anti-inflammatory. Warm compresses and massage of the eyelid are a usual first step but this alone is often not curative.7 Antiinflammatory therapy with topical corticosteroid drops can reduce inflammation but the chronic granulomatous nature of the inflammatory response may not completely resolve with topical therapy. Intralesional steroid injection has been advocated to reduce inflammation.7–9 In recalcitrant cases, evacuation of the chalazion by surgical incision and curettage is necessary.10 Randomized controlled clinical trials have been published that compare efficacy and safety of treatment options and show that treatment with intralesional steroid is as effective as incision and curettage (84 % versus 87%, respectively) in contrast to the conservative management with hot compresses, that resulted in only a 46% resolution.8,9

Repeatedly recurrent or unusually irregular lid lesions mimicking chalazion can be more difficult to diagnose and can certainly be more dangerous, as they are neoplasms of the meibomian gland. It is, therefore, wise to submit curettage specimens for histopathological evaluation in recurrent or unusual circumstances. Sebaceous cell carcinoma is the most worrisome lesion to be identified, but intratarsal keratinous cysts are also an uncommon etiology of a lesion mimicking chalazion.11,12

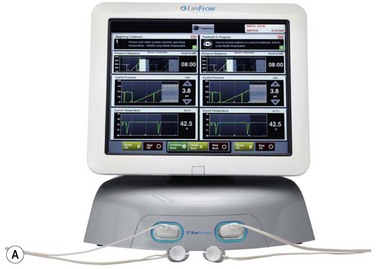

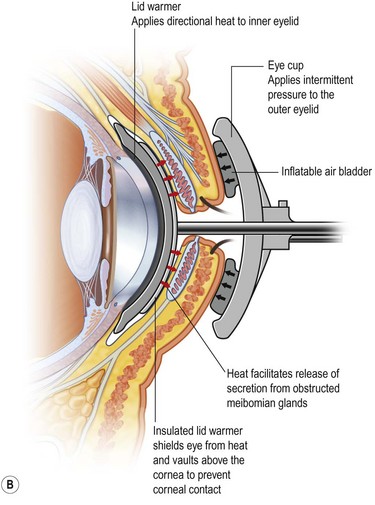

Meibomian gland dysfunction is probably the most common affliction of the meibomian glands and the pathophysiology is amply described in the MGD Report of 2011.1 Obstruction of the meibomian gland orifice by keratinized epithelium or thickened abnormal secretion is the primary initiating pathological event.1,13 Therefore, relief of obstruction is a central goal of therapy. The obstruction of the meibomian gland orifice can be visualized in many cases of MGD but as Blackie, Korb and others have emphasized, nonobvious obstruction is frequent and expression of the eyelid glands as part of the physical examination is essential to diagnosis (Fig. 10.6).14 Including expression of the meibomian glands as part of the routine evaluation of the eyelids during an eye examination, is a pivotal recommendation of the MGD Report. Mechanical options for treatment typically begin with application of warm compresses, two or more times daily, followed by firm massage of the eyelids.15 A variety of techniques have been advocated but one effective, simple approach is well described.15 Other techniques are described in the MGD Report.16 Warming of the eyelid has been accomplished by application of a washcloth soaked in hot water, but more elaborate methods have also been described. Heating a washcloth or a potato in a microwave oven has been advocated to provide a lasting heat, but overheating can occur and lead to burns of the facial skin.17 Reports from the Japanese literature describe heating of the eyelids with an infrared lamp, applied as a controlled mask.18 The application of warm, moist air or steam has also been evaluated.19 A novel approach to application of controlled temperature concurrent with mechanical expression of the eyelids is the Lipiflow™ system, which utilizes pulsed compression of the eyelids during continuous monitored thermal control (Fig. 10.7).20

Figure 10.7 (A) Illustration of the Lipiflow™ System that provides monitored temperature warming and intermittent pulsation of the eyelids. (Courtesy of Tear Sciences, Inc; Morrisville, North Carolina.) (B) Cross-sectional view of Lipiflow™ System when applied to eyelid. (www.tearscience.com/physician/in-officeprocedure/lipid-science (accessed Jan., 2013) )

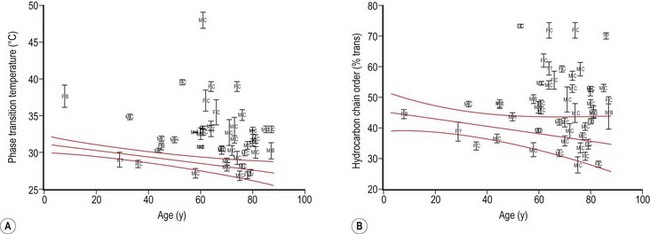

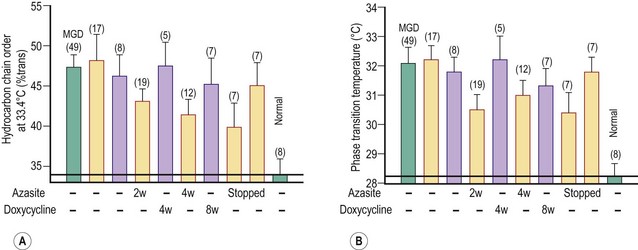

Meibum is a complex mixture of various polar and nonpolar lipids containing cholesteryl esters (CEs), triacylglycerol, free cholesterol, free fatty acids (FFAs), phospholipids, wax esters (WEs), and diesters.21–24 Reported alterations of the behavior and composition of meibum in MGD are summarized in Table 10.1. Changes in the composition and behavior of the meibomian gland secretion (meibum), occurring both with age and due to meibomian gland dysfunction, have been documented by a variety of spectroscopic techniques.38,39 These studies reveal that abnormal behavior of the secretion is due to increased viscosity, resulting from an elevated phase transition temperature that correlates with a higher degree of ordering of the lipid molecules (Fig. 10.8).40 These abnormal properties of the altered meibum can be reversed with several pharmacological therapies (Fig. 10.9).4,41–43 Tetracycline-class drugs (tetracycline, doxycycline, and minocycline) have been shown to alter the abnormal meibum, presumably by interfering with lipase enzymes that degrade the normal lipids into smaller diglycerides.4 Doxycycline has been shown to produce a number of other changes in lipid composition and the presence of caratenoids in the meibum.39 Azithromycin applied topically to the eye and eyelid over a month of therapy is a very effective agent to restore lipid behavior towards normal (Fig. 10.9).41–43 The effect is probably due to a combination of antilipase activity and anti-inflammatory activity as well.45

Table 10.1

Behavior and Composition Changes in Meibum with MGD

| Behavior | |

| Increased phase transition temperature | Borchman, et al. (FTIR)25 |

| Increased ordering of lipid | Foulks, et al. (FTIR)26 |

| Increased viscosity | Borchman, et al. (FTIR)25 |

| Composition | |

| Reduced cholesterol | Mathers, Lane27 |

| Reduced triglycerides | Mathers, Lane27 |

| Reduced polar lipids (PE, SM) | Shine, et al.28 |

| Increased lipid peroxides | Augustin, et al.29 |

| Increased free fatty acids | Shine, et al.30 |

| Increased branched chain fatty acids | Joffre, et al.31 |

| Increased triglyceride saturation | Joffre, et al.31 |

| Change in diglyceride content | Dougherty, et al.32 |

| Increased phospholipid unsaturation | Shine, et al.33 |

| Increased protein content | Borchman, et al.34 |

| Change in saturation of carbohydrate chains | Borchman, et al.10 |

| Decrease oleic acid content | Shine, et al.35 |

| Decreased cholesteryl esters | Shrestha, et al.36 |

| Decrease in terpenoid content | Borchman, et al.37 |

FTIR, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; PE, phosphoethanolamine; SM, sphingomyelin.

Finally, control of inflammation is an important part of the therapy of MGD. Although topical corticosteroids are probably the most effective and most rapid method for controlling inflammation, the duration of such therapy is limited by the side effects of elevated intraocular pressure and cataract formation. Topical therapy with cyclosporine avoids those complications with improvement of MGD but the duration of therapy required is longer than steroids.46 Supplementation of the diet with omega-3 essential fatty acids may also provide some anti-inflammatory benefit, although there are few controlled clinical trials that verify such a benefit, and measurement of meibum does not demonstrate specific effect on the production or composition of the secretion.47,48 The recommended doses of omega-3 essential fatty acids vary but it is probably wise to follow the guidelines of the American Heart Association which advise limiting omega-3 supplements to 2 to 4 grams per day, unless under physician observation.49

Management of MGD

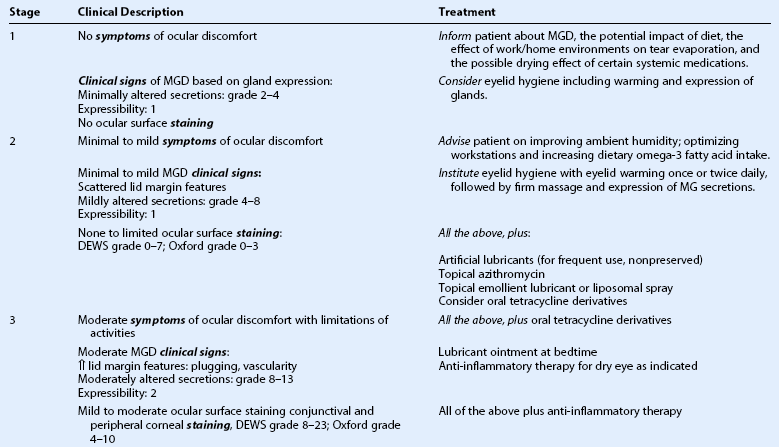

The management strategies for MGD have been well defined and referenced in the 2011 Report of the TFOS Meibomian Gland Workshop with therapy based upon clinical staging of the disease process and the concurrent effect on the tear film and ocular surface.16 In brief, the clinical staging of the meibomian gland dysfunction evaluates the degree of obstruction of the gland orifices, due both to the number of glands obstructed and the amount of pressure needed to release expressate from the gland.50,51 Grading of the character of the meibum is typically done in four categories: clear, turbid, turbid with clumps, and paste (see Fig. 10.4).43,44 The amount of lid swelling and erythema of the lid margin determines the grading of degree of inflammation.50,51 Other lid margin changes indicate the chronicity of the MGD, as cicatricial dragging of the orifices posteriorly onto the conjunctiva, telangiectasia of the lid margin, notching of the eyelid at the site of scarred orifices, and loss of eyelashes occur over time and do not resolve with therapy (see Fig. 10.5).50,51

Expressibility is assessed on a scale of 0 to 3 in five glands in the lower or upper lid, according to the number of glands expressible:

Staining scores are obtained by summing the scores of the exposed cornea and conjunctiva:

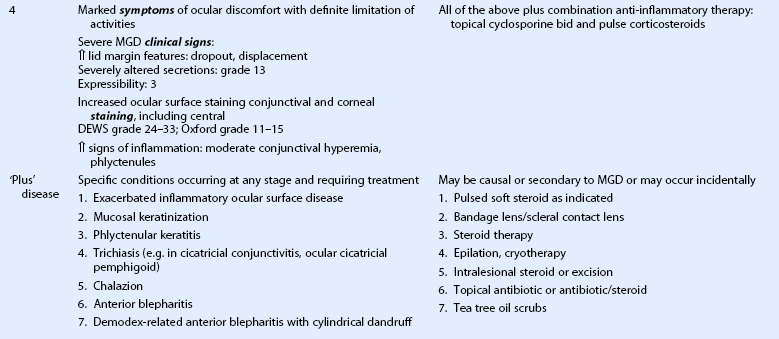

Once the severity level of MGD is determined, an appropriate level of therapy can be selected from the treatment algorithm (Table 10.2).16 Asymptomatic but evident MGD (stage 1) should prompt education of the patient as to the nature and potential progression of disease and the value of prophylactic lid hygiene and massage. Mildly symptomatic disease with increasing evidence of MGD (stage 2) should be treated. If it is determined that the patient’s diet is deficient in omega-3 essential fatty acids, oral supplementation can also be considered.47,48 The clinical trials evaluating the effectiveness of omega-3 essential fatty acid supplementation are few, but the anecdotal evidence is encouraging that there is benefit. The optimal dosage has not been determined for MGD therapy but it is reasonable to follow the American Heart Association guidelines that recommend 2000 to 4000 milligrams per day but no more than 4000 milligrams per day without physician supervision.49 Use of essential fatty acid supplements in patients taking oral anticoagulants is not advisable, as they may alter coagulation of the blood.

Table 10.2

(Adapted and modified from the treatment algorithm of the International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction. Geerling G, Tauber J, Baudouin C, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2011 Mar 30;52:2050–64.)

Concurrent with the evaluation of meibomian gland function, evaluation of the ocular surface/tear film effects of MGD needs to be done by evaluation of tear film stability (tear break up time (TBUT) ) and ocular surface staining.51,53 Therapy to stabilize the tear film is generally directed at restoring the lipid layer of the tear film by use of topical lipid-enhanced lubricants used two to four times daily.54,55 A more recent option to restore the lipid layer stabilizing effect to the tear film is liposomal spray.56 If inflammation of the ocular surface is also present, the use of topical steroid drops or cyclosporine is indicated.

The category of ‘Plus’ disease identifies associated problems that can occur as a result of MGD or in association with MGD. Treatments specific for each associated problem are recommended and are listed in Table 10.2.

There are a number of possible options for relieving obstruction of the meibomian glands that have not yet been fully evaluated in randomized clinical trials but which have been reported to provide relief of symptoms by reducing meibomian gland orifice obstructions. The LipiflowTM System provides pulsed thermal compression of the eyelids. Cannulation of the gland orifices with a specially designed small-bore needle has been reported to relieve symptoms in 75% of patients with MGD.57 Further evaluation of these options in controlled clinical trials is warranted.

The use of topical androgen has also been advocated as there is a growing body of evidence that androgen controls meibomian gland secretion and that reduction of androgen, due to advancing age, menopause in women, or the use of antiandrogen drugs in men undergoing prostate cancer therapy leads to meibomian gland deficiency.58 No randomized clinical trials have yet proved that topical administration of androgen reverses MGD.

Therapeutic Summary (Refer to Table 10.2)

1. Internal hordeolum with acute inflammation

a. Apply hot compresses (to localize and reduce inflammation)

b. Apply topical antibiotic (erythromycin ointment t.i.d., azithromycin b.i.d, or topical fluoroquinolone t.i.d.)

c. If pointing purulent focus, consider lancing at point of lesion.

2. Diffuse disease (meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD) )

1. Evaluate and stage level of severity according to MGD Workshop Report

a. Express glands to determine degree of obstruction and character of meibum

b. Evaluate tear film stability and ocular surface damage by use of topical fluorescein or lissamine green

a. Educate patient about presence of MGD and possible progression

b. Educate patient about effects of environment and activity on tear evaporation and drying effects of systemic medications

c. Evaluate dietary intake of omega-3 essential fatty acids and encourage including fish in diet

d. Consider eyelid hygiene including warming and expression of glands

a. Increase dietary omega 3 intake, including supplements

b. Institute eyelid hygiene with lid warming and firm eyelid expression of MG secretions

c. Consider topical azithromycin daily therapy for at least one month

d. Add lipid-containing artificial tear stabilizing drop b.i.d.

a. All of the above therapy inclusive of oral doxycycline therapy

b. Anti-inflammatory topical therapy as indicated: corticosteroids and/or cyclosporine

a. All of the above therapy and combination anti-inflammatory therapy: topical cyclosporine and pulse corticosteroid

a. Exacerbated inflammatory ocular surface disease: pulsed soft steroid as indicated

b. Mucosal keratinization: bandage contact lens/scleral contact lens

c. Phlyctenular keratitis: steroid therapy

d. Trichiasis (e.g. in cicatricial conjunctivitis, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid): epilation, cryotherapy, radiofrequency ablation

e. Chalazion: intralesional steroid or excision

f. Anterior blepharitis: topical antibiotic or antibiotic/steroid

g. Demodex-related anterior blepharitis, with cylindrical dandruff: tea tree oil scrubs or topical metronidazole lotion

3. Diffuse disease with associated dermatologic condition

References

1. Knop, E, Knop, N, Millar, T, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on anatomy, physiology, and pathophysiology of the meibomian gland. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1938–1978.

2. Nelson, JD, Shimazaki, J, Benitez-del-Castillo, JM, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the definition and classification subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1930–1937.

3. Allali, J, Roche, O, Monnet, D, et al. Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia: congenital ameibomia. J Fr Ophtalmol. 2007;30:525–528.

4. Dougherty, JM, McCulley, JP, Silvany, RE, et al. The role of tetracycline in chronic blepharitis-Inhibition of lipase production in staphylococci. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1991;32:2970–2975.

5. Ramesh, S, Ramakrishnan, R, Bharathi, MJ, et al. Prevalence of bacterial pathogens causing ocular infections in South India. Ind J Pathol Microbiol. 2010;53:281–286.

6. Lindsley, K, Nichols, JJ, Dickersin, K. Interventions for acute internal hordeolum. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 8(9), 2010. [CD007742. Review].

7. Chung, CF, Lai, JS, Li, PS. Subcutaneous extralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection versus conservative management in the treatment of chalazion. Hong Kong Med J. 2006;12:278–281.

8. Goawalla, A, Lee, V. A prospective randomized treatment study comparing three treatment options for chalazia: triamcinolone acetonide injections, incision and curettage and treatment with hot compresses. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35:706–712.

9. Ben Simon, GJ, Rosen, N, Rosner, M, et al. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide injection versus incision and curettage for primary chalazia: a prospective randomized study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151:714–718.

10. Duarte, AF, Moreira, E, Nogueira, A, et al. Chalazion surgery: advantages of a subconjunctival approach. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2009;11:154–156.

11. Shields, JA, Demirci, H, Marr, BP, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids: personal experience with 60 cases. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2151–2157. [Review].

12. Jakobiec, FA, Mehta, M, Iwamoto, M, et al. Intratarsal keratinous cysts of the Meibomian gland: distinctive clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features in 6 cases. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:82–94.

13. Green-Church, KB, Butovich, I, Willcox, M, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on tear film lipids and lipid-protein interactions in health and disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:1979–1993.

14. Blackie, CA, Korb, DR, Knop, E, et al. Nonobvious obstructve meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2010;29:1333–1345.

15. Paranjpe, DR, Foulks, GN. Therapy of meibomian gland disease. Ophthalmol Clin NA. 2003;16:37–42.

16. Geerling, G, Tauber, J, Baudouin, C, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the subcommittee on management and treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2050–2064.

17. Jones, YJ, Georgesuc, D, McCann, JD, et al. Microwave warm compress burns. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;26:219.

18. Mori, A, Oguchi, Y, Goto, E, et al. Efficacy and safety of infrared warming of the eyelids. Cornea. 1999;18:188–193.

19. Matsumoto, Y, Dogru, M, Goto, E, et al. Efficacy of a new warm moist air device on tear functions of patients with simple meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2006;25:644–650.

20. Lane, SS, Dubiner, HB, Epstein, RJ, et al. a new system, the lipiflow, for the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction (mgd). Cornea. 2012;31:396–404.

21. Butovich, IA. The Meibomian puzzle: combining pieces together. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2009;28:483–498.

22. Butovich, IA, Uchiyama, E, Di Pascuale, MA, et al. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometric analysis of lipids present in human meibomian gland secretions. Lipids. 2007;42:765–776.

23. Chen, J, Green-Church, KB, Nichols, KK. Shotgun lipidomic analysis of human meibomian gland secretions with electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:6220–6231.

24. Green-Church, KB, Butovich, I, Willcox, M, et al. The International Workshop on Meibomian Gland Dysfunction: Report of the Subcommittee on Tear Film Lipids and Lipid–Protein Interactions in Health and Disease. Invest Ophthal Vis Sci. 2011;52:1979–1993.

25. Borchman, D, Foulks, GN, Yappert, MC, et al. Human meibum lipid conformation and thermodynamic changes with meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3805–3817.

26. Foulks, GN, Borchman, D, Yappert, M, et al. Topical azithromycin therapy for meibomian gland dysfunction: clinical response and lipid alterations. Cornea. 2010;29:781–788.

27. Mathers, WD, Lane, JA. Meibomian gland lipids, evaporation, and tear film stability. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1998;438:349–360.

28. Shine, WE, McCulley, JP. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with meibomian secretion polar lipid abnormality. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:849–852.

29. Augustin, AJ, Spitznas, M, Kaviani, N, et al. Oxidative reactions in the tear fluid of patients suffering from dry eyes. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 1995;233:694–698.

30. Shine, WE, McCulley, JP. Meibomian gland triglyceride fatty acid differences in chronic blepharitis patients. Cornea. 1996;15:340–346.

31. Joffre, C, Souchier, M, Gregoire, S, et al. Differences in meibomian fatty acid composition in patients with meibomian gland dysfunction and aqueous-deficient dry eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:116–119.

32. Dougherty, JM, McCulley, JP. Analysis of the free fatty acid component of meibomian secretions in chronic blepharitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:52–56.

33. Shine, WE, McCulley, JP. Meibomianitis: polar lipid abnormalities. Cornea. 2004;23:781–783.

34. Borchman, D, Yappert, MC, Foulks, GN. Changes in human meibum lipid with meibomian gland dysfunction using principal component analysis. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:246–256.

35. Shine, WE, McCulley, JP. Association of meibum oleic acid with meibomian seborrhea. Cornea. 2000;19:72–74.

36. Shrestha, RK, Borchman, D, Foulks, GN, et al. Analysis of the composition of lipid in human meibum from normal infants, children, adolescents, adults and adults with meibomian gland dysfunction using 1H-NMR spectroscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:7350–7358.

37. Borchman, D, Foulks, GN, Yappert, MC, et al. differences in human meibum lipid composition with meibomian gland dysfunction using nmr and principal component analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:337–347.

38. Borchman, D, Foulks, GN, Yappert, MC, et al. Spectroscopic evaluation of human tear lipids. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids. 2007;147:87–102.

39. Wojtowicz, JC, Butovich, I, McCulley, JP. Historical brief on human meibum lipids composition. The Ocular Surface. 2009;7:145–153.

40. Borchman, D, Foulks, GN, Yappert, MC, et al. Human meibum lipid conformation and thermodynamic changes with meibomian gland dysfunction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3805–3817.

41. Foulks, GN, Borchman, D, Yappert, MC, et al. Topical azithromycin and oral doxycycline therapy of meibomian gland dysfunction: a comparative and spectroscopic pilot study. Cornea. 2013;32:44–53.

42. Luchs, J. Azithromycin in DuraSite for the treatment of blepharitis. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010;4:681–688.

43. Utine, CA. Update and critical appraisal of the use of topical azithromycin ophthalmic 1% (AzaSite) solution in the treatment of ocular infections. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:801–809.

44. Borchman, D, Foulks, GN, Yappert, MC, et al. Differences in human meibum lipid composition with meibomian gland dysfunction using NMR and principal component analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:337–347.

45. Sadrai, Z, Hajrasouliha, AR, Chauhan, S, et al. Effect of topical azithromycin on corneal innate immune responses. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2525–2531.

46. Perry, HD, Doshi-Carnevale, S, Donnenfeld, ED, et al. Efficacy of commercially available topical cyclosporine A 0.05% in the treatment of meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2006;25:171–175.

47. Macsai, MS. The role of omega-3 dietary supplementation in blepharitis and meibomian gland dysfunction (an AOS thesis). Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2008;106:336–356.

48. Wojtowicz, JC, Butovich, I, Uchiyama, E, et al. Pilot, prospective, randomized, double-masked, placebo-controlled clinical trial of an omega-3 supplement for dry eye. Cornea. 2011;30:308–314. [Erratum in: Cornea. 2011;30:1521].

49. American Heart Association Recommendations for Fish in Diet. Available at http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/GettingHealthy/NutritionCenter/Fish-101_UCM_305986_Article.jsp. [(last accessed 18 Jan 2013)].

50. Foulks, GN, Bron, AJ. Meibomian Gland dysfunction. a clinical scheme for description, diagnosis, classification, and grading. The Ocular Surface. 2003;1:107–126.

51. MGD Workshop diagnosis and gradingTomlinson, A, Bron, AJ, Korb, DR, et al. The international workshop on meibomian gland dysfunction: report of the diagnosis subcommittee. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2006–2049.

52. Bron, AJ, Evans, VE, Smith, JA. Grading of corneal and conjunctival staining in the context of other dry eye tests. Cornea. 2003;22:640–650.

53. The 2007 Report of the International Dry Eye Workshop (DEWS). Ocular Surface. 2007;5:107–152.

54. Foulks, GN. The correlation between the tear film lipid layer and dry eye disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52:369–374.

55. Benelli, U. Systane lubricant eye drops in the management of ocular dryness. Clin Ophthalmol. 2011;5:783–790.

56. Craig, JP, Purslow, C, Murphy, PJ, et al. Effect of a liposomal spray on the pre-ocular tear film. Cont Lens Anterior Eye. 2010;33:83–87.

57. Maskin, SL. Intraductal meibomian gland probing relieves symptoms of obstructive meibomian gland dysfunction. Cornea. 2010;29:1145–1152.

58. Sullivan, DA, Sullivan, BD, Evans, JE, et al. Androgen deficiency, meibomian gland dysfunction, and evaporative dry eye. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2002;966:211–222.