Chapter 49 MEDICAL PROBLEMS AFTER LIVER TRANSPLANTATION

REJECTION OF THE LIVER GRAFT

Chronic rejection

Chronic rejection, despite the inference that it is a late event, can occur within 6 weeks of liver transplantation. It is characterised by an elevated serum bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltransferase. It is more insidious in progression than acute rejection and is characterised by histological features of paucity of bile ducts associated with arteriole obstruction by foamy macrophages. Chronic rejection does not respond to pulse methylprednisolone. Some patients who are on cyclosporine will benefit from conversion to tacrolimus, and patients already using tacrolimus may benefit from an increased dosage to achieve higher serum levels.

INFECTIONS IN THE LIVER TRANSPLANT RECIPIENT

It is useful to consider the type of infections in relationship to the time since liver transplantation. Bacterial infections are extremely common in the first month after liver transplantation and common sites of infection include the abdomen (peritonitis, cholangitis, hepatic abscess, wound infection), chest (pneumonia, empyema), urinary tract (a consequence of prolonged catheterisation) and intravenous access sites. A definitive focus of bacterial sepsis may not be found or may be unusually located (e.g. teeth or prostate gland). The viral infections that occur early after liver transplantation include herpes simplex virus (HSV) reactivation, which may be manifest by oral or genital lesions, and HHV-6, which may cause pancytopenia and interstitial pneumonia. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is extremely common after liver transplant but tends to occur after the first month. The clinical manifestations may be protean and include cytopenia, hepatitis, upper and lower gastrointestinal tract ulceration, pulmonary involvement and an infectious mononucleosis syndrome. Diagnosis may be confirmed by the characteristic histological appearance of inclusion bodies in addition to the detection of a circulating structural protein (pp65) and direct identification of virus by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). However, it is recognised that diagnosis may be very difficult on occasions. Ganciclovir is the antiviral of choice and dose adjustments are required for patients with renal failure (see below for antimetabolite interactions). Similarly, reactivation of varicella tends to occur slightly later after liver transplant and can manifest as shingles, disseminated cutaneous disease or visceral involvement. Epstein-Barr virus infection tends to present as a post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder that may respond to a reduction in the intensity of immunosuppression. The prevalence of opportunistic infections also relates to the intensity of the immunosuppressive regime. While the frequency of opportunistic infection is proportional to the intensity of the immunosuppression regime, patients are always at risk. Vigilance is required for infections with fungi (Aspergillus, Cryptococcus, Candida), protozoans (Pneumocystis carinii, Toxoplasma gondii) and bacteria (Nocardia, Legionella).

IMMUNOSUPPRESSION THERAPY

Drug interactions

The terminal metabolism of cyclosporine and tacrolimus occurs via the cytochrome P450 system. Therefore, agents that alter cytochrome P450 activity—whether it be increased or decreased—have the potential to influence their blood levels resulting in drug toxicity or under-immunosuppression. Important inducers of cytochrome P450 metabolism include the following medications:

Two other immunosuppressive drug interactions are worthy of note. An increased incidence of rhabdomyolysis has been reported in patients receiving concomitant cyclosporine and HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (‘statins’) and rhabdomyolysis can occur at any time while patients are on these medications. Unfortunately, hyperlipidaemia is a well recognised side effect of cyclosporine and lipid lowering agents are frequently indicated in the post-transplant patient. Statins should be commenced at low dose and routine monitoring of creatinine phosphokinase is recommended. Grapefruit juice can markedly augment levels of immunosuppressive agents by selective post-translational down-regulation of intestinal wall cytochrome P450. There is significant interindividual variation in the susceptibility to this interaction, however patients should be warned about the potential for this interesting drug interaction.

There are two issues of note regarding drug interactions with azathioprine:

Long-term medical complications

Renal complications

Renal dysfunction is common after liver transplantation and has multiple aetiologies. Hypertension, diabetes mellitus and drug-induced nephrotoxicity—either alone or in combination—are responsible for the majority of cases of renal dysfunction. The renal effects of tacrolimus and cyclosporine can take several forms including renal vasoconstriction, thrombotic angiopathy and, in the chronic form, tubular atrophy and interstitial fibrosis with preservation of glomerular structure. A complete history and physical examination are important to exclude other potential contributing factors. The dose of cyclosporine or tacrolimus should be minimised, sometimes by using a small dose of another kidney sparing agent (e.g. azathioprine).

RECURRENCE OF THE UNDERLYING DISEASE

Chronic liver disease due to hepatitis C virus infection is the most common indication for liver transplantation worldwide. Unfortunately, the infection recurs in almost every patient following transplantation. An acute lobular hepatitis develops in 75% of patients within 6 months of liver transplantation, and this can be difficult to distinguish from acute rejection on liver biopsy. A small proportion of patients (approximately 5%) will develop a specific, accelerated course of liver injury termed fibrosing cholestatic hepatitis, which is usually fatal. Approximately 30% of patients will develop cirrhosis by 5 years after transplantation. Thus the course of liver disease in patients with recurrent HCV infection following liver transplantation is greatly compressed compared with non-transplant patients. A number of factors associated with aggressive recurrence have been identified (Table 49.1). Studies utilising pegylated interferon and ribavirin have reported sustained virological response of 25%–35% although dose reductions of both pegylated interferon and ribavirin are common (80%) and therapy has to be ceased in approximately 25% of patients.

TABLE 49.1 Risk factors associated with severe histological recurrence of hepatitis C virus

Recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma is uncommon if patients are transplanted when there is a single tumour less than 5 cm in diameter, or no more than three lesions less than 3 cm (Milan criteria) and no evidence of portal vein invasion. Factors that predict increased likelihood of recurrence include vascular invasion and poorly differentiated tumours. Most units regard cholangiocarcinoma as a contraindication to transplantation as recurrence is almost universal. Extensive clinical research trials are being performed at some centres in an effort to identify patients with ‘favourable’ cholangiocarcinoma.

VASCULAR AND BILIARY COMPLICATIONS

Portal vein thrombosis

Portal vein thrombosis may occur early or some time after transplantation. Occlusion of the portal vein early after transplantation may be associated with a marked elevation of alanine aminotransferase and diagnosis is confirmed by duplex ultrasonography. Early surgical intervention or re-transplantation may be required. In the later postoperative course, portal vein occlusion may present with gastrointestinal bleeding associated with the development of collateral vessel formation or may be asymptomatic. The most appropriate management of a portal vein thrombosis in this situation is dependent on a number of different issues.

SUMMARY

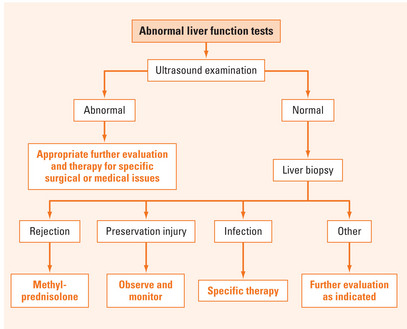

Liver transplantation is a widely available treatment for patients with liver disease. In the early years of transplantation, 1-year and 5-year survival were regarded as the core determinants of a successful transplant program. However, in recent years clinicians have recognised that medical complications related to immunosuppression are the most important determinant of long-term survival of liver transplant patients. As such, proper management of medical issues such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and renal dysfunction are the central tenets of care of these patients. This chapter highlights the importance of these issues and provides basic instruction on the medical complications seen in the liver transplant patient (Figure 49.1).

Fischer SA. Infections complicating solid organ transplantation. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:1127-1145.

Killenberg PG, Clavien P-A, editors. Medical care of the liver transplant patient, 3rd edn., Malden MA: Blackwell Science, 2006.

Muñoz SJ, Elgenaidi H. Cardiovascular risk factors after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(supp 1):S52-S56.

Wilkinson A, Pham P. Kidney dysfunction in the recipients of liver transplants. Liver Transpl. 2005;11(supp 1):S47-S51.