Meckel Diverticulum

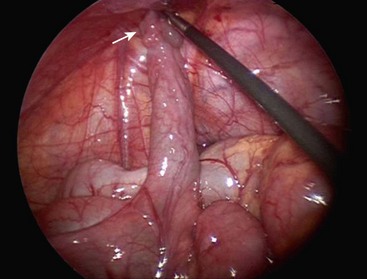

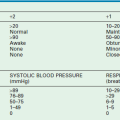

Wilhelm Fabricius Hildanus, a German surgeon, first described the presence of a small bowel diverticulum in 1598.1 However, the diverticulum is named for Johann Meckel, a German anatomist, who further described the anatomy and embryology in 1809.2 Meckel diverticulum is a remnant of the embryologic vitelline (omphalomesenteric) duct that connects the fetal gut with the yolk sac and normally involutes between the fifth and seventh weeks of gestation. Failure of duct regression results in a variety of abnormalities arising from persistence of the remnant (Fig. 40-1). The most common anomaly (90%) is the classic Meckel diverticulum. It is a true diverticulum, consisting of all normal layers of the bowel wall. Clinical symptoms and complications can arise from small bowel obstruction, bleeding, inflammation, umbilical abnormalities, or neoplasia.

FIGURE 40-1 Drawings illustrating Meckel diverticulum and other remnants of the yolk sac. (From Moore KL. The Developing Human. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1988.)

Epidemiology

The true incidence of Meckel diverticulum is unknown, since most patients are asymptomatic. While the incidence is typically estimated at approximately 2%, a recent systematic review of autopsy studies found an incidence of 1.2%.3 The incidence may be increased in patients with major anomalies of the umbilicus, alimentary tract, nervous system, or cardiovascular system.4 An estimated 4% of patients with Meckel diverticulum will become symptomatic, and the risk of developing symptoms decreases with age.5 A recent report based on data from the Pediatric Health Information System database found that 53% of Meckel diverticulectomies are performed before 4 years of age, with a male : female ratio of 2.3 : 1 overall and 3 : 1 in symptomatic patients.6 The commonly cited ‘rule of 2s’ regarding the diverticulum is: occurs in 2% of the population, has a 2 : 1 male : female ratio, usually discovered by 2 years of age, located 2 feet (60 cm) from the ileocecal valve, commonly 2 cm in diameter and 2 inches (5 cm) long, and can contain two types of heterotopic mucosa.7 Gastric is the most common type of heterotopic mucosa, followed by pancreatic (Fig. 40-2).8 More rarely, it may contain duodenal, colonic, or endometrial tissue.

Clinical Presentation

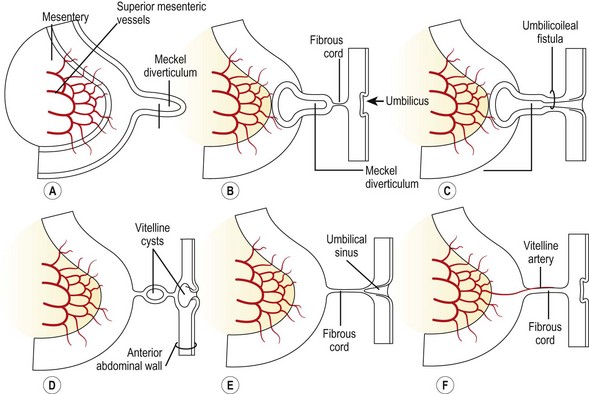

A variety of symptoms can develop depending on the configuration of the remnant structure and the presence of ectopic mucosa. The three most common presentations in children are intestinal bleeding (30–56%), intestinal obstruction (14–42%), and diverticular inflammation (6–14%).8–10 Other less common signs include a cystic abdominal mass11 and a newborn with an umbilical fistula resulting from a patent vitelline duct (Fig. 40-3). A Littré hernia refers to a Meckel diverticulum found incarcerated in a hernia which may be located at the inguinal, femoral, umbilical or Spigelian sites.12 In adults, especially the elderly, neoplasia can develop within the Meckel diverticulum. Carcinoid is the most common tumor, but other malignancies include adenocarcinoma, leiomyosarcoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and lymphoma.13 Neonatal presentation of a Meckel diverticulum is uncommon and typically is due to perforation or obstruction.14

FIGURE 40-3 This neonate was born with an obvious patent omphalomesenteric duct. (A) Meconium was seen to emanate from the stoma. (B) A circumumbilical incision was made, and the duct (arrow) was dissected to its connection with the ileum. (C) The duct was amputated from the ileum and the umbilical incision closed. The patient recovered uneventfully and has not developed any further problems.

Bleeding

Bleeding is generally attributed to the presence of heterotopic mucosa. Gastric mucosa is present in up to 80% of Meckel diverticula that bleed.15 Gastric acid produces mucosal ulceration, typically at the junction of the ectopic mucosa and the normal ileal mucosa. The ulcer may also be located within the ectopic mucosa or even on the mesenteric side of the normal ileum, opposite the diverticulum. While Helicobacter pylori is associated with many ulcers in the duodenum and stomach, studies have shown that H. pylori is rarely present in a bleeding Meckel diverticulum.16,17

Obstruction

A Meckel diverticulum can cause intestinal obstruction through several mechanisms, but most commonly intussusception or volvulus. The diverticulum can act as a lead point for an obstructing ileo-ileal and subsequent ileo-colic intussusception. A volvulus can occur if bowel twists or kinks around a vitelline remnant with a fibrous cord between the diverticula and umbilicus (see Fig. 40-1). An internal hernia can result due to a mesodiverticular artery, coursing from the base of the mesentery to the diverticulum, under which the small bowel becomes entrapped and incarcerated. Other rare obstructing mechanisms include an incarcerated Littré hernia, and a long diverticulum that may knot on itself or twist around its base.

Inflammation

Inflammation of the diverticulum is often attributed to the presence of heterotopic gastric or pancreatic tissue. Obstruction of the diverticular lumen can also produce inflammation, similar to the mechanism for appendicitis. Lumenal obstruction can occur due to stasis of enteric contents within the diverticulum, the presence of an enterolith or foreign body, or even parasitic infections.18–20 Meckel diverticulitis is often misdiagnosed as appendicitis due to similar presenting symptoms, including periumbilical pain that may be associated with nausea, vomiting, and fever. The point of maximal tenderness on physical exam may migrate within the abdomen. Given the possibility of misdiagnosis, the intraoperative finding of a normal appendix in a child suspected of having appendicitis should lead to a careful search for a Meckel diverticulum. Due to variability in the location of the diverticulum, at least 5 feet of distal small bowel should be examined, starting at the terminal ileum and working proximally. Meckel diverticulitis can also result in perforation, intra-abdominal abscess, and obstructive signs and symptoms.

Diagnosis

In patients presenting with obstruction or inflammation, the diagnosis of a Meckel diverticulum is not typically determined preoperatively. On the other hand, in a child older than 5 years of age who has not undergone an abdominal operation and presents with signs and symptoms of small bowel obstruction, a Meckel diverticulum should be strongly considered as the etiology. The diagnosis of intussusception is often confirmed by ultrasound (US) or air enema, but rarely identifies a pathologic lead point, such as a Meckel diverticulum. Air enema may reduce the ileocolic portion of the intussusception, but often the ileo-ileal component is not successfully reduced. If it is reduced, symptoms will often recur. When present, the diverticulum will be discovered either intraoperatively or when the resected segment of intestine is examined. An inflamed Meckel diverticulum is often misdiagnosed as appendicitis and found intraoperatively after a normal appendix is removed. In some cases, a preoperative computed tomography scan or ultrasound may find an inflamed midline mass with a normal appendix, suggesting the correct diagnosis.

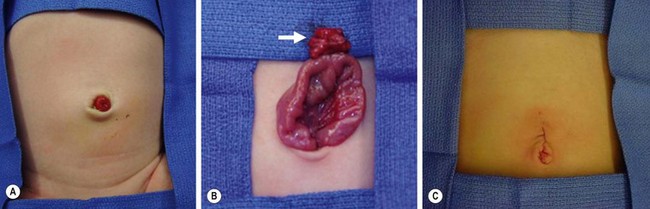

Preoperative studies can often determine the etiology in patients presenting with lower gastrointestinal bleeding. In addition to a Meckel diverticulum, the differential diagnosis includes anal fissure, intestinal polyps, inflammatory bowel disease, intestinal duplications, hemangiomas, and arteriovenous malformations. A complete history and physical can help exclude some potential bleeding sources. Placement of a nasogastric tube can exclude an upper gastrointestinal source as well. The preferred radiologic test is the technetium-99m pertechnetate radionuclide study (‘Meckel scan’). This imaging study relies on the fact that most bleeding Meckel diverticula contain ectopic gastric mucosa. The intravenously injected technetium-99m pertechnetate is taken up and secreted by the tubular gland cells of gastric mucosa. Scintigraphy can then visualize focal accumulation of the tracer in the diverticulum (Fig. 40-4).

FIGURE 40-4 Technetium-99m pertechnetate scan of a patient with a Meckel diverticulum. Note the blush (arrow) above the bladder. (Courtesy of Kyo Lee, MD.)

Active bleeding is not required to achieve a positive result with scintigraphy, unlike angiography or tagged red blood cell scan. However, false negatives can occur if the diverticulum does not contain gastric mucosa or if it is lying low in the pelvis and obscured by the bladder. Other types of ectopic mucosa will not take up the radiotracer. False positives can also occur as a result of intestinal duplications, bowel obstruction or inflammation, intussusception, arteriovenous malformations, ulcers, and some neoplasms.21 Pharmacologic uptake enhancement with the use of pentagastrin or histamine-2 blockers may improve the accuracy of the study. However, the high rate of false negatives raises some concerns. Also, while the positive predictive value of scintigraphy is near 100% and specificity is over 95%, the sensitivity may be as low as 60%, with a negative predictive value of 75%.15 Therefore, a negative scan does not exclude the possibility of a Meckel diverticulum, and several authors have recommended diagnostic laparoscopy for definitive evaluation, especially in cases with anemia and high clinical suspicion for a bleeding diverticulum.15,22

Other tests useful in the evaluation of intestinal bleeding include mesenteric angiography and a technetium-99m tagged red blood cell scan. Angiography is limited to cases with significant acute hemorrhage as it is invasive and requires active bleeding of at least 0.5 ml/min. A tagged red cell scan requires bleeding of at least 0.1 mL/min and may be more sensitive but less specific for localizing the bleeding source. Upper and lower endoscopy will not allow visualization of a Meckel diverticulum, but these tests are helpful to evaluate for other disorders that may produce rectal bleeding. Wireless capsule endoscopy and double-balloon enteroscopy techniques have also been utilized to identify a Meckel diverticulum.23,24 While these modalities are not used regularly, they may be helpful when all other tests have failed to identify the site of bleeding.

Treatment

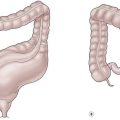

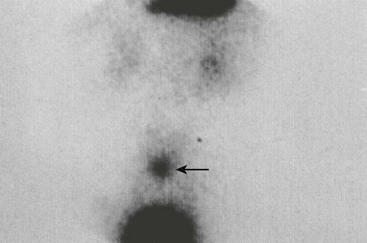

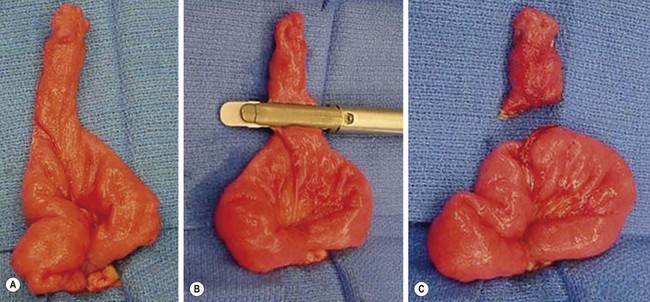

Resection may be accomplished by either simple diverticulectomy or segmental ileal resection with anastomosis. In patients with obstruction, simple diverticulectomy is often sufficient, but all ectopic tissue should be removed. If a Meckel diverticulum is discovered after reduction of an intussusception, diverticulectomy may be possible, though segmental ileal resection may be safer depending on the appearance of the bowel (Fig. 40-5). In cases of bleeding, an ulcer may be present at the base of the diverticulum or on the mesenteric side of the ileum. Therefore, segmental resection is typically regarded as the safest approach to ensure removal of the bleeding source and avoid the risk of recurrent bleeding. The specimen should be opened after resection to confirm that it contains the ulcer.

FIGURE 40-5 A 4-year-old child presented with an irreducible intussusception and required an operative reduction. (A) Note the small bowel intussuscepted into the large bowel. (B) After reduction of the ileum, a Meckel diverticulum was found to be the lead point for the intussusception. (C) The diverticulum was excised with an endoscopic stapler.

Laparoscopy is now commonly utilized for resection of a Meckel diverticulum as it can be both diagnostic and therapeutic.22,25 The diverticulum may be resected with either an intracorporeal technique, or grasped and exteriorized through the umbilicus for an extracorporeal diverticulectomy or segmental resection (Fig. 40-6). Port placement for the intracorporeal approach is similar to the set-up for laparoscopic appendectomy, with a 12 mm umbilical cannula and two 5 mm cannulas in the left lower quadrant. Laparoscopic-assisted extracorporeal resection is generally preferred in infants and small children, due to limited intra-abdominal working space, which makes the use of staplers cumbersome. Segmental resection is also more easily accomplished extracorporeally. More recently, reports have described a single-incision laparoscopic approach.26,27

FIGURE 40-6 This is the patient identified in Figure 40-2. (A) When diagnosed, Meckel diverticulum can be managed either totally intracorporeally or exteriorized through the umbilical incision. (B, C) The diverticulum and a small segment of the ileum just proximal and distal to the diverticulum were exteriorized through the umbilicus and the diverticulum was excised using the endoscopic stapler. The excision was done in an oblique direction to avoid narrowing the ileum at the site of the diverticulectomy.

Management of an asymptomatic incidentally found diverticulum remains controversial. Operative intervention is not indicated for an asymptomatic diverticulum discovered incidentally on imaging studies. When a Meckel diverticulum is found intraoperatively, several reports recommend resection due to the risk of malignancy or other future complications.9,13,28 However, other studies conclude that the risk of complications is less than the risk of complications following resection.2,4 Still others recommend a selective approach, depending on characteristics of the diverticulum, such as length >2 cm, presence of ectopic mucosa, male gender, and age younger than 50 years.8 Given the lack of clear consensus, the decision to resect an incidentally discovered Meckel diverticulum should be based on the surgeon’s clinical judgment.

References

1. Daniels, IR. Historical perspectives on health: Johann Friendrich Meckel the younger and his diverticulum. J R Soc Promot Health. 2000; 120:125–126.

2. Meckel, J. Uber die divertikel am darmkanal. Arch Physiol. 1809; 9:421.

3. Zani, A, Eaton, S, Rees, CM, et al. Incidentally detected Meckel diverticulum: To resect or not to resect? Ann Surg. 2008; 247:276–281.

4. Simms, MH, Corkery, JJ. Meckel diverticulum: Its association with congenital malformation and the significance of atypical morphology. Br J Surg. 1980; 67:216–219.

5. Soltero, MJ, Bill, AH. The natural history of Meckel diverticulum and its relation to incidental removal: A study of 202 cases of diseased Meckel diverticulum found in King County, Washington, over a fifteen-year period. Am J Surg. 1976; 132:168–173.

6. Ruscher, KA, Fisher, JN, Hughes, CD, et al. National trends in the surgical management of Meckel diverticulum. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:893–896.

7. Pepper, VK, Stanfill, AB, Pearl, RH. Diagnosis and management of pediatric appendicitis, intussusception, and Meckel diverticulum. Surg Clin N Am. 2012; 92:505–526.

8. Park, JJ, Wolff, BG, Tollefson, MK, et al. Meckel Diverticulum: The Mayo Clinic experience with 1476 patients (1950–2002). Ann Surg. 2005; 241:529–533.

9. St-Vil, D, Brandt, ML, Panic, S, et al. Meckel diverticulum in children: A 20-year review. J Pediatr Surg. 1991; 26:1289–1292.

10. Menezes, M, Tareen, F, Saeed, A, et al. Symptomatic Meckel diverticulum in children: A 16-year review. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008; 24:575–577.

11. Oguzkurt, P, Strlic, M, Kayaselcuk, F, et al. Cystic Meckel diverticulum: A rare cause of cystic pelvic mass presenting with urinary symptoms. J Pediatr Surg. 2001; 36:1855–1858.

12. Skandalakis, PN, Zoras, O, Skandalakis, JE, et al. Littre hernia: Surgical anatomy, embryology, and technique of repair. Am Surg. 2006; 72:238–243.

13. Thirunavukarasu, P, Sathaiah, M, Sukumar, S, et al. Meckel Diverticulum—A high-risk region for malignancy in the ileum. Ann Surg. 2011; 253:223–230.

14. Aguayo, P, Fraser, JD, St. Peter, SD, et al. Perforated Meckel diverticulum in a micropremature infant and review of the literature. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009; 25:539–541.

15. Swaniker, F, Soldes, O, Hirschl, RB. The utility of technetium 99m pertechnetate scintigraphy in the evaluation of Meckel diverticulum. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 34:760–765.

16. Ergun, O, Celik, A, Akarca, US, et al. Does colonization of Helicobacter pylori in the heterotopic gastric mucosa play a role in bleeding of Meckel diverticulum? J Pediatr Surg. 2002; 37:1540–1542.

17. Tuzun, A, Polat, Z, Kilciler, G, et al. Evaluation for Helicobacter pylori in Meckel diverticulum by using real-time PCR. Dig Dis Sci. 2010; 55:1969–1974.

18. Pantongrag-Brown, L, Levine, MS, Buetow, PC, et al. Meckel enteroliths: Clinical, radiologic, and pathologic findings. AJR. 1996; 167:1447–1450.

19. Weissberg, D. Foreign bodies within a Meckel diverticulum. Arch Surg. 1992; 127:864.

20. Chirdan, LB, Yusufu, LM, Ameh, EA, et al. Meckel diverticulum due to Taenia saginata: Case report. East Afr Med J. 2001; 78:107–108.

21. Sfakianakis, GN, Conway, JJ. Detection of ectopic gastric mucosa in Meckel diverticulum and in other aberrations by scintigraphy: ii. Indications and methods—a 10-year experience. J Nucl Med. 1981; 22:732–738.

22. Shalaby, RY, Soliman, SM, Fawy, M, et al. Laparoscopic management of Meckel diverticulum in children. J Pediatr Surg. 2005; 40:562–567.

23. Fritscher-Ravens, A, Scherbakov, P, Bufler, P, et al. The feasibility of wireless capsule endoscopy in detecting small intestinal pathology in children under the age of 8 years: A multicentre European study. Gut. 2009; 58:1467–1472.

24. Uchiyama, S, Sannomiya, I, Hidaka, H, et al. Meckel diverticulum diagnosed by double-balloon enteroscopy and treated laparoscopically: Case report and review of the literature. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010; 20:278–280.

25. Chan, KW, Lee, KH, Mou, JWC, et al. Laparoscopic management of complicated Meckel diverticulum in children: A 10-year review. Surg Endosc. 2008; 22:1509–1512.

26. Clark, J, Koontz, C, Smith, L, et al. Video-assisted transumbilical Meckel diverticulectomy in children. Am Surg. 2008; 74:327–329.

27. Garey, CL, Laituri, CA, Ostlie, DJ, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic surgery in children: Initial single-center experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:904–907.

28. Onen, A, Cigdem, MK, Ozturk, H, et al. When to resect and when not to resect an asymptomatic Meckel diverticulum: An ongoing challenge. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003; 19:57–61.