Chapter 6 Mechanobullous disorders

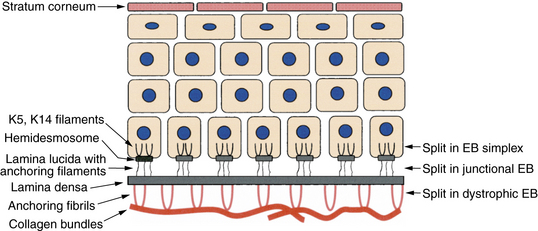

Figure 6-1. Layers of the skin with major sites of splitting in epidermolysis bullosa (EB).

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

Key Points: Heritable Blistering Disorders

Figure 6-5. Recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Severe scarring resulting in loss of functional digits.

Das BB, Sahoo S: Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa, J Perinatol 24:41–47, 2004.

Lai-Cheong JE, McGrath JA: Kindler syndrome, Dermatol Clin 28(1):119–124, 2010.

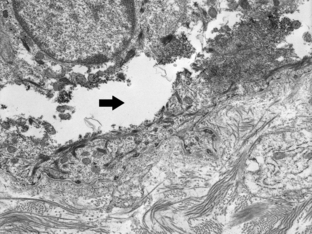

Figure 6-7. Electron microscopic study of an induced blister in EB simplex demonstrating a split (arrow) in the cytoplasm of the basilar keratinocyte.

(Courtesy of James E. Fitzpatrick, MD.)

When dealing with a newborn with suspected EB it is best to contact one of the national organizations that deals with EB, such as the Dystrophic EB Research Association (www.DebRA.org), which can provide both clinical as well as family support. In addition, one can contact one of the five large multidisciplinary EB clinics in North America (Stanford University, Stanford, CA; Children’s Hospital, Aurora, CO; Cincinatti Children’s Hospital, OH; Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada; and Columbia University, New York).

Fassihi H, Ashton GH, Denyer J, et al: Prenatal diagnosis of Herlitz junctional epidermolysis bullosa in nonidentical twins, Clin Exp Dermatol 30:180–182, 2005.