Maximizing Outcomes

Relating Interventions to an Individual’s Needs

As direct access to patients becomes globally accepted, the capacity of the physical therapist to diagnose problems that are amenable to, as well as not amenable to, physical therapy is crucial for effective, safe, and responsible care. After formulating the diagnoses in partnership, as much as possible, with the patient and consistent with the health care team overall, the physical therapist prioritizes the diagnoses to address those most critical to the patient. These diagnoses may not necessarily be the reason the individual initially sought care from, or was referred to, a physical therapist. This is the essence of evidence-informed practice in the context of epidemiological indicators as distinct from evidence-based practice that supports the effectiveness of specific interventions (see Chapter 1).

This chapter provides a basis for clinical decision making and intervention prescription in physical therapy for patients ranging from the individual who is medically unstable and critically ill to the individual who is medically stable with cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction or at risk and living in the community. In addition, physical therapists have an active role in wellness and its promotion in the form of structured programs as well as one-on-one care. Thus the individuals they counsel include those with cardiovascular and pulmonary pathologies secondary to impairments or threats of other organ systems as well as those with primary impairments or threats of the cardiovascular and pulmonary systems (see Chapter 6).

Clinical reasoning is the process of critically analyzing the patient’s status (participation in life and activities, as well as anatomic structures or physiological function) with respect to the individual’s psychosocial, cultural, and environmental contexts (see Chapters 1 and 17). What is the individual able to do (and not able to do)? What is the status of the organ systems? How do these two interrelate? The answers to these questions serve as the basis of the detailed diagnostic work-up by the physical therapist. This process results in the diagnoses or problems that are then prioritized to ensure that the patient’s needs are addressed appropriately—that is, “the right interventions targeted at the right problems at the right time.” Initial priorities include life-preserving interventions (including addressing threats) and the minimizing of physical and psychological distress. Facilitators and barriers to the patient’s adhering to the intervention recommendations, including health literacy and lifestyle education, are clearly identified, and education and interventions are adapted to meet the needs of the individual. With this database, the physical therapist prescribes interventions so that their outcomes are maximized in the short term and the long term.

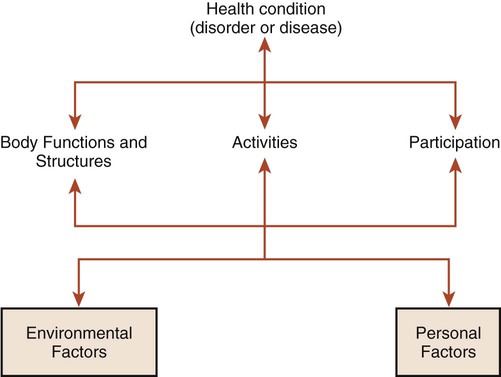

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

Participation

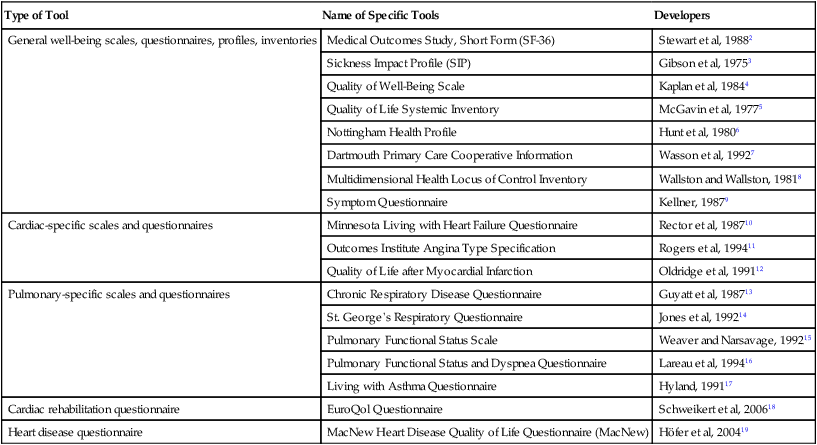

For most individuals, the highest priority is the capacity to live a life consistent with their needs and wants according to their sociocultural norms. The World Health Organization (WHO) acknowledges this in its International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, which emphasizes the interrelationship among structure and function, activity, and participation in life. Health has been defined by WHO as emotional, spiritual, intellectual, and physical well-being—not merely the absence of pathology.1 Participation refers to the capacity of individuals to fulfill these needs in a social context and thereby fulfill the multiple roles in their lives—as parent, child, sibling, employee, employer, student, or homemaker, as well as in avocational pursuits (Figure 17-1). Participation in life is assessed by open-ended questions asked during the history and interview. In addition, an increasing number of questionnaire tools and scales are available for clinical use. Table 17-1 outlines some common generic and condition-specific tools that can be used to assess quality of life, life satisfaction, sickness impact, and subjective sense of well-being. These can be useful outcome measures (technically, these scales provide scores that are indexes rather than actual measures of the constructs) for the physical therapist and the patient. Many of these scales have been shown to be reliable as well as valid. Validating these scales is conceptually and methodologically challenging; hence their limitations must be recognized.

Table 17-1

Tools for Evaluating Domains of Quality of Life (Activity and Participation)

| Type of Tool | Name of Specific Tools | Developers |

| General well-being scales, questionnaires, profiles, inventories | Medical Outcomes Study, Short Form (SF-36) | Stewart et al, 19882 |

| Sickness Impact Profile (SIP) | Gibson et al, 19753 | |

| Quality of Well-Being Scale | Kaplan et al, 19844 | |

| Quality of Life Systemic Inventory | McGavin et al, 19775 | |

| Nottingham Health Profile | Hunt et al, 19806 | |

| Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information | Wasson et al, 19927 | |

| Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Inventory | Wallston and Wallston, 19818 | |

| Symptom Questionnaire | Kellner, 19879 | |

| Cardiac-specific scales and questionnaires | Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire | Rector et al, 198710 |

| Outcomes Institute Angina Type Specification | Rogers et al, 199411 | |

| Quality of Life after Myocardial Infarction | Oldridge et al, 199112 | |

| Pulmonary-specific scales and questionnaires | Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire | Guyatt et al, 198713 |

| St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire | Jones et al, 199214 | |

| Pulmonary Functional Status Scale | Weaver and Narsavage, 199215 | |

| Pulmonary Functional Status and Dyspnea Questionnaire | Lareau et al, 199416 | |

| Living with Asthma Questionnaire | Hyland, 199117 | |

| Cardiac rehabilitation questionnaire | EuroQol Questionnaire | Schweikert et al, 200618 |

| Heart disease questionnaire | MacNew Heart Disease Quality of Life Questionnaire (MacNew) | Höfer et al, 200419 |

Activity

Participation in life and fulfilling one’s roles and obligations require the ability to perform a range of certain activities to some level of proficiency (see Figure 17-1). The role of a parent, for example, requires being able to identify the needs of children, as well as to plan and coordinate activities involved with their care (e.g., picking them up, bathing and dressing them, performing physical activities and playing with them, and taking them to school). With respect to occupational roles, for example, to fulfill the needs of being a truck driver, the individual needs to be able to get to work, climb into the truck, check the engine, crawl under the truck, load and unload the truck, read a map, and operate a standard transmission. To be an elementary school teacher requires being able to move around the classroom, help children with physical tasks, and anticipate their needs, stay alert to danger, and respond quickly. The physical therapist’s assessment must identify the composite activities that are limited and that affect an individual’s capacity to participate in fulfilling his or her roles.

Structure and Function

Limitations of anatomic structure and physiological function often interfere with the performance of specific activities that are involved in fulfilling roles and obligations in life (i.e., participating in life) (see Figure 17-1). Some limitations may be specific to a particular role, and some may interfere across roles. The physical therapy assessment identifies the limitations of structure and function and the degree to which they interfere with given activities and roles in life. Some limitations of structure and function related to oxygen transport do not necessarily limit activity or participation; yet they can be the most clinically important, life-threatening problems (e.g., high blood pressure, cardiac dysrhythmias, abnormal clotting factors, high blood glucose, and aerobic deconditioning). Given the prevalence of lifestyle-related conditions and their risk factors, each individual needs to be assessed for risk for heart disease, smoking-related conditions, hypertension and stroke, diabetes, and cancers (see Chapter 1). Assessment of a patient’s bone health and risk for osteoporosis and arthritis is also prudent, especially now that individuals are generally living longer and often have lifestyles that predispose them to osteopenia and osteoporosis. Physical therapists have a primary role in assessing these risks for several reasons:

First, these problems can be the most important clinically in terms of health and threat to life (chronic morbidity and premature death) for the patient, either directly or indirectly.

Second, identifying these problems enables the physical therapist to work collaboratively with the health care team in addressing and following the patient in a coordinated, integrated manner. If a patient was not referred and new problems are detected, the physician needs to be alerted. With direct-access practice, this is a primary responsibility of the contemporary physical therapist. If risk factors have been identified or have manifested clinically, the patient may be taking medication or may be a candidate for surgery. The physical therapist has a primary role in avoiding or minimizing the need for invasive care (specifically, drugs and surgery)—this is a particularly important and often underestimated goal of the physical therapist, who is committed to using and promoting noninvasive care. The physical therapist must closely monitor a patient’s responses to invasive care (i.e., drugs and surgery) in relation to problems of direct relevance to them, with the intention of reducing such intervention.

Third, the physical therapist needs to institute relevant and targeted health education for lifelong behavior change (i.e., assess the patient’s needs, including health literacy, knowledge deficits about health and health status, learning readiness, and learning style; tailor the education materials to the learner; and assess the outcome of the educational intervention comparable to other physical therapy interventions) (see Chapters 1 and 27).

Fourth, the presence of risk factors may require a higher level of patient monitoring, including the results of invasive testing (e.g., blood work for cholesterol, triglycerides, and blood glucose) and other tests such as imaging results and ECGs.

Fifth, physical therapy interventions and their prescriptive parameters may need to be modified based on an individual’s risk factors for lifestyle-related conditions.

Sixth, special attention to medications may be indicated, and these may need to be coordinated with physical therapy management.

Seventh, the presence of risk factors for lifestyle-related conditions requires long-term management and follow-up.

Psychosocial and cultural factors are assessed to identify beliefs, attitudes, lifestyle behaviors, and expectations of care (see Chapter 1). A learning assessment (see Chapter 28) is conducted to identify health literacy and knowledge deficits, the learning style of the patient, and readiness to participate in intervention. Identifying facilitators and barriers that will impact the outcome of the therapeutic relationship is central to ensuring maximal therapeutic outcomes, including an individual’s subjective sense of well-being and empowerment.

What are the problems with respect to participation, activity, and structure and function (impairments)? What are the interrelationships among these problems? (Remember: The interrelationships will be specific to the individual).

What are the problems with respect to participation, activity, and structure and function (impairments)? What are the interrelationships among these problems? (Remember: The interrelationships will be specific to the individual).

What is the prognosis—with and without intervention?

What is the prognosis—with and without intervention?

What is the relationship between the prognosis for each problem and the objectives of intervention and prescription?

What is the relationship between the prognosis for each problem and the objectives of intervention and prescription?

What are the intervention priorities, and why?

What are the intervention priorities, and why?

What are the interventions of choice, and why?

What are the interventions of choice, and why?

What are the prescriptive parameters for each, and why? How should they be sequenced, and why?

What are the prescriptive parameters for each, and why? How should they be sequenced, and why?

What is the course of intervention, and why? What are the requirements for follow-up in the short and long term, and why?

What is the course of intervention, and why? What are the requirements for follow-up in the short and long term, and why?

What are the boundaries of knowledge that would guide a physical therapist to refer a patient to another health care professional (e.g., counselor, nutritionist, personal trainer, physician, psychologist)?

What are the boundaries of knowledge that would guide a physical therapist to refer a patient to another health care professional (e.g., counselor, nutritionist, personal trainer, physician, psychologist)?

The principles involved in relating cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapy interventions to the patient’s needs depend on an analysis of those needs with respect to the patient’s level of participation in life and ability to perform the identified composite activities. The degree to which limitations of anatomic structure and physiological function (with a focus on impairments of the steps in the oxygen transport pathway; Chapter 2) affect activity and participation is assessed. The relationship of impairment to an individual’s ability and participation cannot be assumed. Verification can be extracted from the history and overall assessment, including measures and indexes of the individual’s capacity to perform activities and participate in life. These aspects of the assessment can be obtained through the use of standardized questionnaire tools that reveal the impact of health-related quality of life and sickness; these tools can be used as outcome measures in conjunction with measures of anatomic structure and physiological function (see Table 17-1). Changes in structure and function with intervention may or may not have a corresponding effect on health-related quality of life or sickness. For example, high blood pressure is most often asymptomatic, but the patient may be prescribed a stringent exercise program and education program. Such knowledge may help to identify those individuals whose quality of life is most likely to improve, as well as where intervention should be targeted.20

The physical therapist formulates a physiologically based intervention hierarchy based on the premise that physiological function, including oxygen transport, is optimal when humans are upright and moving (see Chapters 18, 19, and 20). Applying a systematic physiological approach to diagnosis and the analysis of the patient’s problems, with respect to limitations in the oxygen transport pathway, leads directly to identifying effective interventions. Such an approach provides a rational basis for modifying or discontinuing intervention based on the use of appropriate outcome measures.

What Is the Problem?

Consistent with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, there are three primary levels of analysis:21

These components are affected by facilitating factors and barriers (see Figure 17-1).21 Structure and function refer to the underlying anatomic and physiological limitations that may or may not contribute to the patient’s symptoms but are clinically important and warrant remediation or being addressed in management. Limitation of activities contributes to a compromised capacity to fulfill one’s roles in life, such as those of occupation, profession, parent, and member of various groups that make up an individual’s identity. Usually, a patient presents clinically with complaints of being unable to complete tasks or fulfill roles because of pathophysiological, psychological, or environmental and physical barriers and limitations.

Measures and tools are standardized (concerning validity and reliability, see Chapter 7) for the assessment of each of these levels. With an increased focus on the quality of participation in life, numerous scales have emerged to quantify the subjective sense of well-being and health-related quality of life (see Table 17-1 for some examples).

Oxygen transport is determined by a multitude of factors that affect the steps in the oxygen transport pathway, thereby affecting participation in life and related activities (see Figure 17-1; see Chapter 2).22–24 For intervention to be directed specifically to the underlying problems, the physical therapist needs to consider several levels of analysis of the deficits contributing to impaired or threatened oxygen transport. To be proficient in such analysis, the physical therapist must have a thorough knowledge of the multiple factors that contribute to normal gas exchange and those that contribute to abnormal gas exchange. This knowledge base includes a thorough understanding of the relevant anatomy and physiology; the multisystem and integrative pathophysiology; the impact of medical, surgical, and nursing procedures; the effects of various laboratory tests and procedures; and the impact of pharmacological agents on cardiovascular and pulmonary function (Box 17-1). Assessment of oxygen transport reserve and reserve capacity is fundamental to the management of all patients25 and their risk factors,26 regardless of disease acuity. Routine procedures contribute to fluctuations in oxygen demands.27 Maximizing the ratio of oxygen delivery to consumption improves clinical outcomes in patients who range from being medically stable to being unstable.28,29,30

For a given patient, the cardiovascular and pulmonary physical therapist prescribes intervention by extracting the relevant information from the history, the laboratory tests and investigative procedures, and the assessment (Box 17-2; see Part II). Although physical therapists are primarily noninvasive practitioners, they use and request the results of invasive tests and investigations in their assessments and evaluations. Problems are prioritized on the basis of the relative magnitude of each problem’s threat or effect on oxygen transport limitation, along with the evidence supporting the effectiveness of various noninvasive interventions in addressing each diagnosis or problem. Once the mechanisms of the cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction have been identified, specific interventions are selected and prioritized and the prescriptive parameters of each intervention are then defined. With respect to education, a learning assessment is an essential component of the overall assessment; it identifies health status knowledge deficits and prescribes learning interventions consistent with the patient’s needs (see Chapter 28).

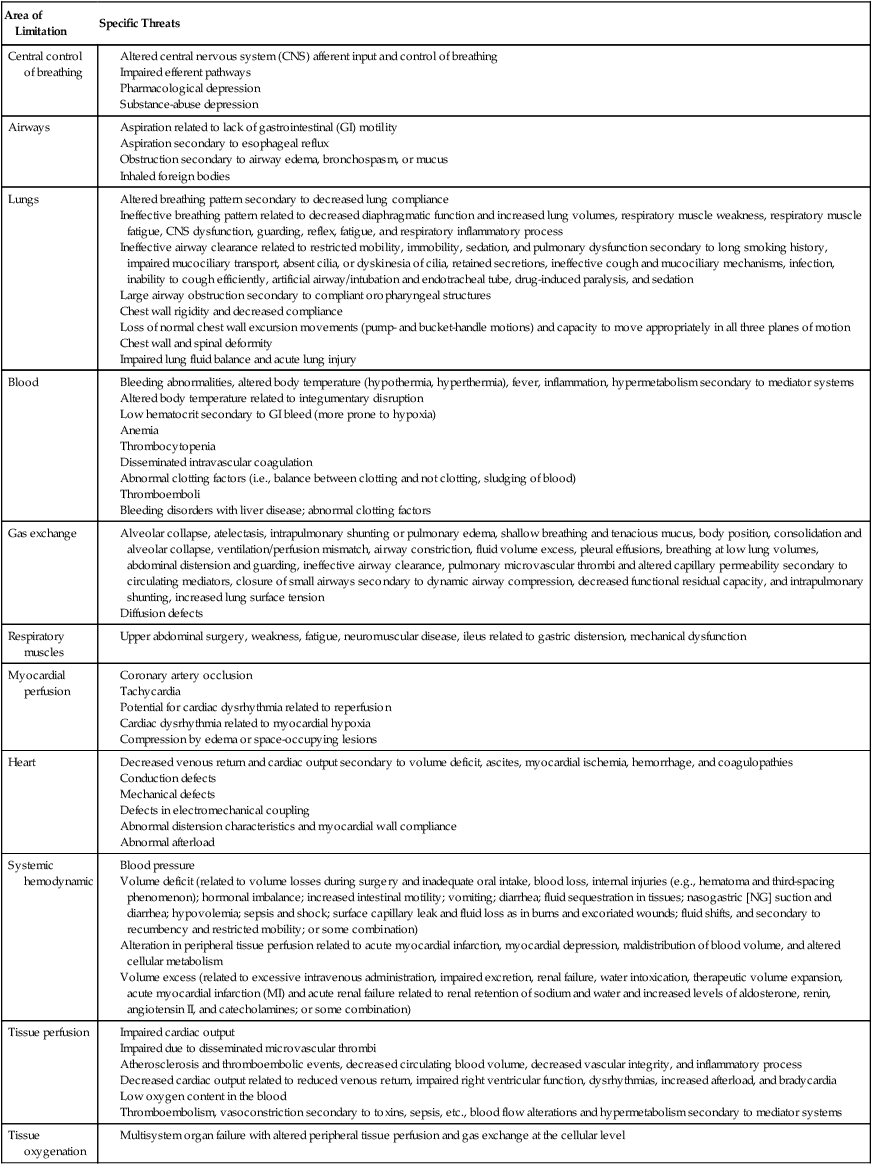

The Diagnoses or Problems

Impaired Oxygen Transport

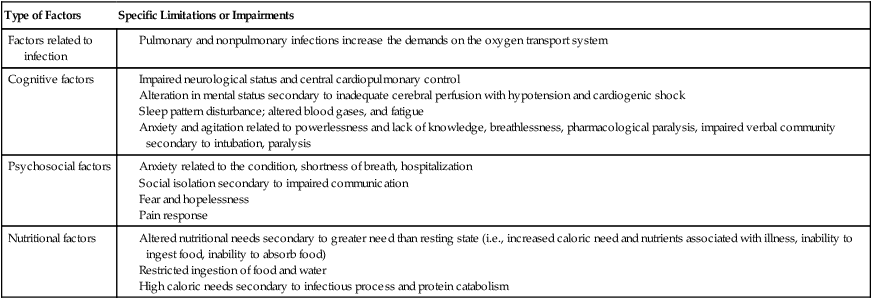

Anatomic and physiological limitations are the individual’s overall deficits in oxygen transport and those that specifically arise at the individual steps in the pathway. Examples of the limitations at each step in the pathway appear in Tables 17-2 and 17-3.

Table 17-2

Examples of Limitations and Threats to the Steps in the Oxygen Transport Pathway

| Area of Limitation | Specific Threats |

| Central control of breathing |

Altered breathing pattern secondary to decreased lung compliance

Ineffective breathing pattern related to decreased diaphragmatic function and increased lung volumes, respiratory muscle weakness, respiratory muscle fatigue, CNS dysfunction, guarding, reflex, fatigue, and respiratory inflammatory process

Ineffective airway clearance related to restricted mobility, immobility, sedation, and pulmonary dysfunction secondary to long smoking history, impaired mucociliary transport, absent cilia, or dyskinesia of cilia, retained secretions, ineffective cough and mucociliary mechanisms, infection, inability to cough efficiently, artificial airway/intubation and endotracheal tube, drug-induced paralysis, and sedation

Large airway obstruction secondary to compliant oropharyngeal structures

Chest wall rigidity and decreased compliance

Loss of normal chest wall excursion movements (pump- and bucket-handle motions) and capacity to move appropriately in all three planes of motion

Bleeding abnormalities, altered body temperature (hypothermia, hyperthermia), fever, inflammation, hypermetabolism secondary to mediator systems

Altered body temperature related to integumentary disruption

Low hematocrit secondary to GI bleed (more prone to hypoxia)

Disseminated intravascular coagulation

Abnormal clotting factors (i.e., balance between clotting and not clotting, sludging of blood)

Bleeding disorders with liver disease; abnormal clotting factors

Alveolar collapse, atelectasis, intrapulmonary shunting or pulmonary edema, shallow breathing and tenacious mucus, body position, consolidation and alveolar collapse, ventilation/perfusion mismatch, airway constriction, fluid volume excess, pleural effusions, breathing at low lung volumes, abdominal distension and guarding, ineffective airway clearance, pulmonary microvascular thrombi and altered capillary permeability secondary to circulating mediators, closure of small airways secondary to dynamic airway compression, decreased functional residual capacity, and intrapulmonary shunting, increased lung surface tension

Volume deficit (related to volume losses during surgery and inadequate oral intake, blood loss, internal injuries (e.g., hematoma and third-spacing phenomenon); hormonal imbalance; increased intestinal motility; vomiting; diarrhea; fluid sequestration in tissues; nasogastric [NG] suction and diarrhea; hypovolemia; sepsis and shock; surface capillary leak and fluid loss as in burns and excoriated wounds; fluid shifts, and secondary to recumbency and restricted mobility; or some combination)

Alteration in peripheral tissue perfusion related to acute myocardial infarction, myocardial depression, maldistribution of blood volume, and altered cellular metabolism

Volume excess (related to excessive intravenous administration, impaired excretion, renal failure, water intoxication, therapeutic volume expansion, acute myocardial infarction (MI) and acute renal failure related to renal retention of sodium and water and increased levels of aldosterone, renin, angiotensin II, and catecholamines; or some combination)

Impaired due to disseminated microvascular thrombi

Atherosclerosis and thromboembolic events, decreased circulating blood volume, decreased vascular integrity, and inflammatory process

Decreased cardiac output related to reduced venous return, impaired right ventricular function, dysrhythmias, increased afterload, and bradycardia

Low oxygen content in the blood

Thromboembolism, vasoconstriction secondary to toxins, sepsis, etc., blood flow alterations and hypermetabolism secondary to mediator systems

Table 17-3

Factors That Can Contribute Indirectly to Oxygen Transport Limitations or Impairments

Threatened Oxygen Transport

Although the complications of restricted mobility and static body positions are well understood, the precise prescription parameters for mobilization and body positioning to avoid these complications have not been defined in detail (see Chapters 18, 19, and 20). With respect to cardiovascular and pulmonary complications, a 1- or 2-hourly turning regimen is commonly accepted. For the patient who is flaccid or comatose, range-of-motion (ROM) exercises every several hours facilitates blood flow through dependent areas and enhances alveolar ventilation, as well as mobilizing joints and muscles. Antiembolic stockings and pneumatic compression devices are routinely used to minimize circulatory stasis in the legs and thereby the potential for thrombi formation.

Factors That Contribute to or Threaten Oxygen Transport

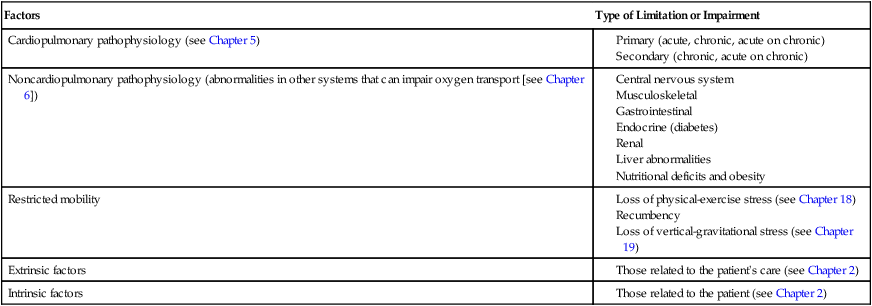

The factors that can impair oxygen transport directly or can threaten it fall into four primary categories (Table 17-4): the underlying cardiovascular and pulmonary pathophysiology, restricted mobility (loss of physical exercise stress), recumbency (loss of vertical gravitational stress), extrinsic factors (i.e., factors related to the patient’s care), and intrinsic factors (i.e., factors related to the patient).

Table 17-4

Factors That Can Limit or Impair Oxygen Transport

| Factors | Type of Limitation or Impairment |

| Cardiopulmonary pathophysiology (see Chapter 5) |

Restricted Mobility and Recumbency

Although bed rest can be considered an extrinsic factor (i.e., a therapeutic intervention that contributes to cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction), the negative consequences of this intervention are often not appreciated fully because of the widespread use of rest in bed. To emphasize the importance of considering the effects of this intervention with each patient, the effects of restricted mobility and recumbency are analyzed separately (see Chapters 18, 19, and 20).

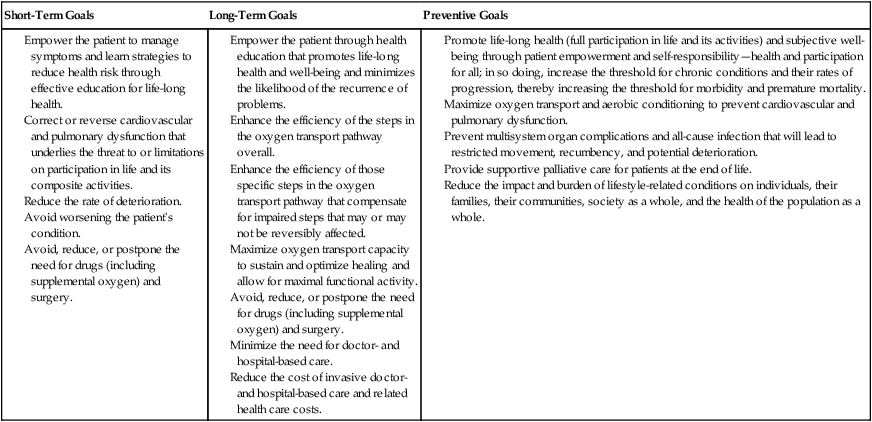

Intervention Goals

Once the deficits and threats to oxygen transport have been determined by the physical therapist, the goals of intervention fall into three categories: short-term, long-term, and preventive (Table 17-5). In addition to improving the outcomes of primary physical therapy interventions, physical therapists seek to eliminate, reduce, or delay the need for invasive care (i.e., drugs and surgery) as much as possible. These are core contemporary physical therapy goals.

Table 17-5

Empower the patient through health education that promotes life-long health and well-being and minimizes the likelihood of the recurrence of problems.

Enhance the efficiency of the steps in the oxygen transport pathway overall.

Enhance the efficiency of those specific steps in the oxygen transport pathway that compensate for impaired steps that may or may not be reversibly affected.

Maximize oxygen transport capacity to sustain and optimize healing and allow for maximal functional activity.

Avoid, reduce, or postpone the need for drugs (including supplemental oxygen) and surgery.

Minimize the need for doctor- and hospital-based care.

Reduce the cost of invasive doctor- and hospital-based care and related health care costs.

Promote life-long health (full participation in life and its activities) and subjective well-being through patient empowerment and self-responsibility—health and participation for all; in so doing, increase the threshold for chronic conditions and their rates of progression, thereby increasing the threshold for morbidity and premature mortality.

Maximize oxygen transport and aerobic conditioning to prevent cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction.

Prevent multisystem organ complications and all-cause infection that will lead to restricted movement, recumbency, and potential deterioration.

Provide supportive palliative care for patients at the end of life.

Reduce the impact and burden of lifestyle-related conditions on individuals, their families, their communities, society as a whole, and the health of the population as a whole.

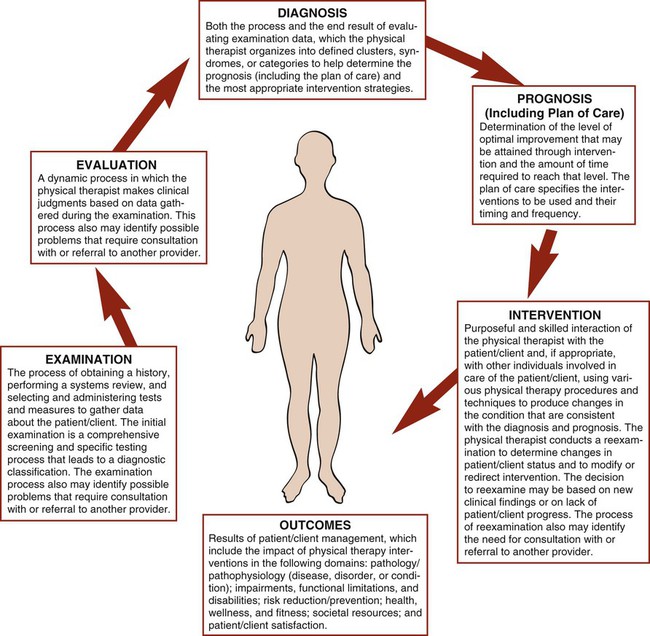

Practice Patterns

The American Physical Therapy Association’s (APTA’s) Guide to Physical Therapist Practice (2003)31 has evolved over the past couple of decades, and it currently reflects a broad scope of practice. The Guide describes examination (history, systems review, and tests and measures), evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis (including plan of care), and intervention (with anticipated goals and expected outcomes). Each physical therapy area of practice has multiple associated practice patterns. Each practice pattern addresses reexamination, global outcomes, and criteria for termination of physical therapy services. Given the APTA’s adoption of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health,21 the evaluation consists of a review of health rather than strictly a primary focus on illness. The iterative cycle of clinical decision making based on outcomes and the modification of interventions is designed to achieve the expected outcomes within a prescribed time frame (Figure 17-2). Based on the consensus of several hundred clinicians in the United States, several primary practice patterns have been defined for each specialty. Once patients are evaluated, their profiles may be described by one or more practice patterns, within one or more specialty areas of practice. There are eight practice patterns in the cardiovascular and pulmonary area (Box 17-3). These patterns and the Guide (2003)31 provide an overall frame of reference for practice rather than serving as a basis for practice. Patients are increasingly complex, given increasing life expectancy and concomitant comorbidities, coupled with lifestyle-related factors and their impact on the patient’s presenting complaint or underlying risk factors. Therefore categorizing a patient in one or more practice patterns may be insufficient to address the patient’s complaints. These patterns serve as guides only. They are not diagnoses, nor do they replace sound clinical reasoning and judgment.

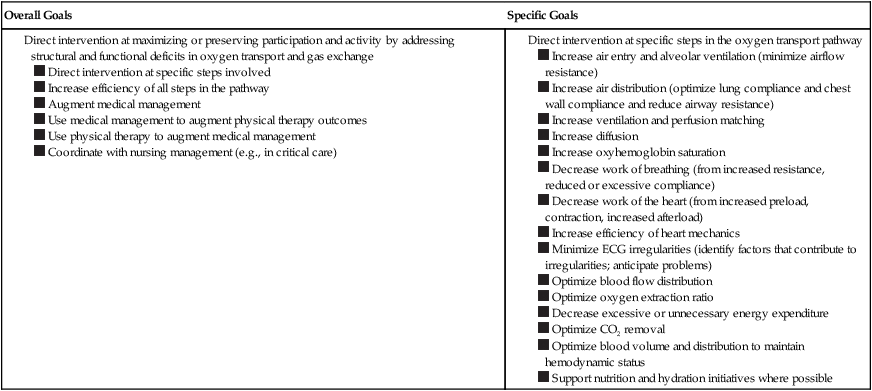

What is the Intervention, and Why?

Clinical Decision Making

Examples of some common intervention goals in managing the patient with cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction are shown in Box 17-4. Specific interventions are identified to address these goals and for each deficit or threat to oxygen transport. Intervention goals and specific interventions are prioritized according to the relative significance of the impact of each on oxygen transport.

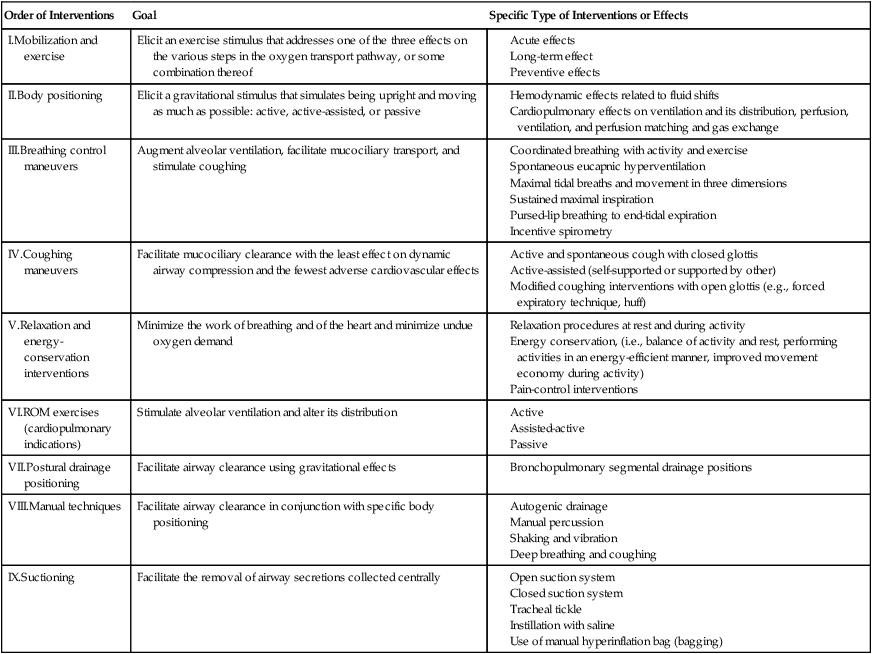

A physiologically based intervention hierarchy is shown in Table 17-6. The intervention hierarchy is based on the premise that physiological function, including oxygen transport, is optimal when a person is upright and moving. Thus the purpose of the hierarchy is to implement the interventions that are most physical first: active movement and exercise in the upright position. The hierarchy ranges from these to the interventions that are the least physical: conventional chest physical therapy techniques such as ROM, postural drainage and percussion, and suctioning. The latter may simulate some of the physiological effects of being upright and moving, but their effects are more limited and less scientifically substantiated, and they facilitate fewer steps in the oxygen transport pathway. They do not substitute for the more active physical interventions that are higher in the intervention hierarchy. Each of the interventions in the hierarchy has a role in the management of cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction or its risks, but they are implemented in descending order to ensure that the most effective interventions are used first.

Table 17-6

| Order of Interventions | Goal | Specific Type of Interventions or Effects |

| I.Mobilization and exercise | Elicit an exercise stimulus that addresses one of the three effects on the various steps in the oxygen transport pathway, or some combination thereof | |

| II.Body positioning | Elicit a gravitational stimulus that simulates being upright and moving as much as possible: active, active-assisted, or passive | |

| III.Breathing control maneuvers | Augment alveolar ventilation, facilitate mucociliary transport, and stimulate coughing | |

| IV.Coughing maneuvers | Facilitate mucociliary clearance with the least effect on dynamic airway compression and the fewest adverse cardiovascular effects | |

| V.Relaxation and energy-conservation interventions | Minimize the work of breathing and of the heart and minimize undue oxygen demand | |

| VI.ROM exercises (cardiopulmonary indications) | Stimulate alveolar ventilation and alter its distribution | |

| VII.Postural drainage positioning | Facilitate airway clearance using gravitational effects | |

| VIII.Manual techniques | Facilitate airway clearance in conjunction with specific body positioning | |

| IX.Suctioning | Facilitate the removal of airway secretions collected centrally |

Intervention Prescription

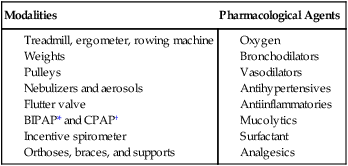

Problems amenable to physical therapy are prioritized. Optimal interventions are identified for each problem, and their parameters are prescribed. The intervention goals are identified: to reverse pathophysiological mechanisms contributing to impaired oxygen transport: to compensate for irreversible pathophysiological deficits (improve the efficiency of other steps in the oxygen transport pathway); to decelerate deterioration; to avoid making the patient worse; to provide palliative care, support, and comfort; and to prevent the occurrence of problems in the future (see Intervention Goals, earlier in this chapter). Based on the goals of intervention, the parameters of the intervention are defined. Intervention parameters in the management of a patient with cardiovascular and pulmonary problems are shown in Box 17-5. To achieve these goals, a range of modalities and aids may be needed in the short term and in the long term (Box 17-6).

What Is the Course of Intervention?

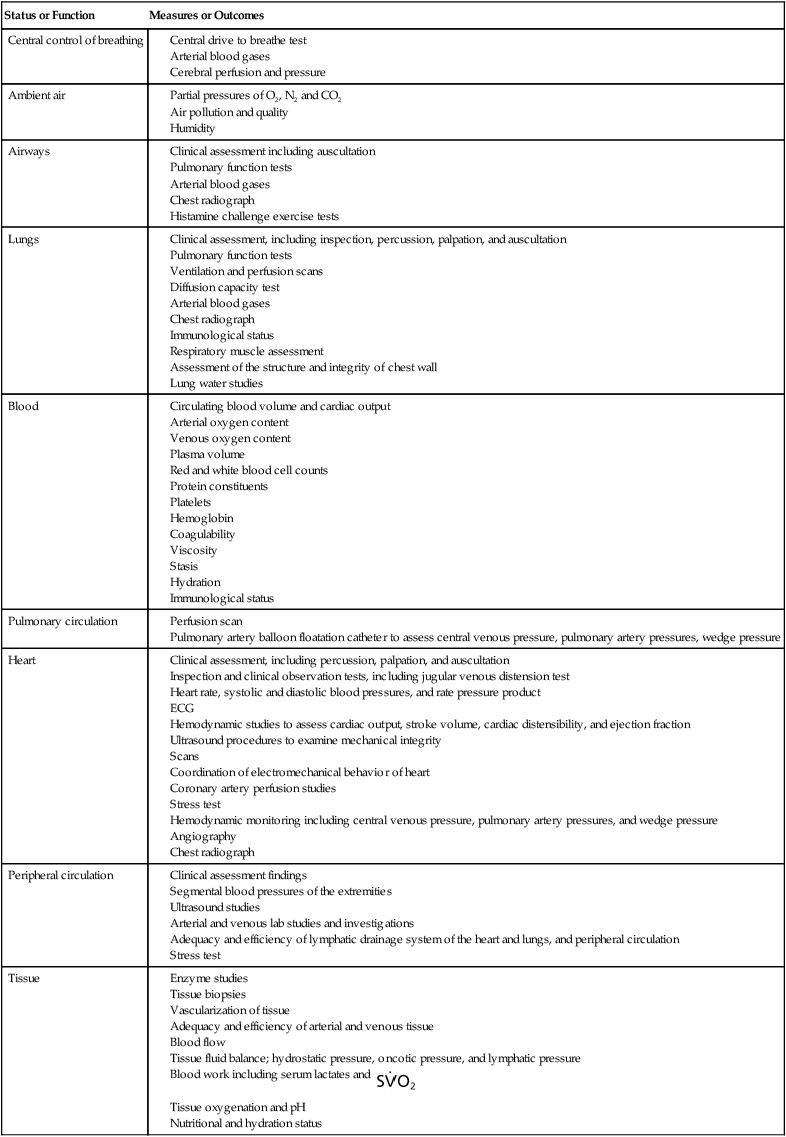

Measures to assess response and outcome to interventions are selected so that they reflect (1) activity and participation status, (2) the status of oxygen transport overall, and (3) the integrity of the step or steps in the oxygen transport pathway that were identified as being the primary problems contributing to cardiovascular and/or pulmonary dysfunction in the original assessment (Table 17-7; see Part II). Cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction is determined on the basis of the history, assessment, and laboratory investigations such as pulmonary function testing, breathing pattern, cardiac function testing, fluid balance and renal function, arterial blood gases, arterial saturation, vital signs, and hemodynamic variables, including heart rate and ECG, blood pressure, and rate pressure product. Subjective reports are also clinically relevant, such as subjective ratings of perceived exertion, breathlessness, musculoskeletal or wound pain, angina, and fatigue. These same measures are used as outcome measures to detect improved oxygen transport and gas exchange.

Table 17-7

Measures and Outcomes to Assess Limitations in the Steps in the Oxygen Transport Pathway

| Status or Function | Measures or Outcomes |

| Central control of breathing |

Clinical assessment, including percussion, palpation, and auscultation

Inspection and clinical observation tests, including jugular venous distension test

Heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, and rate pressure product

Hemodynamic studies to assess cardiac output, stroke volume, cardiac distensibility, and ejection fraction

Ultrasound procedures to examine mechanical integrity

Coordination of electromechanical behavior of heart

Coronary artery perfusion studies

Hemodynamic monitoring including central venous pressure, pulmonary artery pressures, and wedge pressure

Considering that clinical decision making is based largely on the results of tests and measures, it is essential that these measures have certain characteristics. Measurements must be objective and their procedures standardized to maximize test validity and reliability. Although physical therapists specialize in noninvasive assessment procedures as well as interventions, noninvasive measures are prone to imprecision, thereby leading to measurement error and unreliability. It is therefore essential that assessment measurements be performed in a systematic manner and according to measurement guidelines in order to maximize their quality and usefulness in guiding and directing intervention (Chapter 7). Invasive interventions, including blood work, scans, and radiographs, are also fundamental to the physical therapist’s assessment and ongoing evaluation. Assessment measurements always precede intervention to ensure that the intervention and its prescriptive parameters are appropriate. Measurements during intervention provide information about the patient’s responses, both beneficial and detrimental. This feedback determines the parameters of intervention and whether the intervention should be modified in some way or possibly discontinued. The overall intervention response is established by further monitoring and assessment at the termination of intervention and often at periodic intervals post-intervention so that delayed effects can be monitored. Frequent and periodic measurements over time are referred to as serial measurements and provide useful trend data. The pre- and post-intervention responses and any noteworthy responses during intervention are charted, along with sufficient information about the procedures that were used (i.e., assessment, as well as intervention procedures).

Summary

This chapter provides a framework for clinical reasoning and decision making based on oxygen transport characteristics that underlie a limitation in activity and participation in life as defined by the model of ability advocated by the World Health Organization.21 Carried out in partnership with the patient, as much as possible, the process includes diagnoses and intervention prescriptions in the management of patients with cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction, who range from the individual who is medically unstable and critically ill to the individual who is medically stable with cardiovascular and pulmonary dysfunction, or its risk, and living in the community. The purpose of a systematic approach to clinical decision making is to maximize intervention outcome and cost effectiveness. This is done by focusing on physiological and evidence-based practice within the context of evidence-informed practice (i.e., informed by epidemiology) and monitoring to gauge improvement after every intervention so as to ensure that the patient is progressing and time is not wasted. The clinical decision-making process involves diagnosis (i.e., specific analysis of the patient’s problems—limitations in activity and participation) in relation to the physiology and underling pathophysiology, the contribution of restricted mobility and recumbency, and extrinsic (related to the patient’s care) and intrinsic (related to the patient’s characteristics) factors. Based on this analysis, interventions and their parameters are prescribed so that they have the greatest physiological and scientific justification for being likely to return an individual to health and participation in life. Interventions and their prescription parameters should have clear and justifiable rationales. Specific monitoring of the impaired steps in the oxygen transport pathway is essential to establishing and confirming the diagnoses, determining the potentially most effective interventions, evaluating the intervention response, refining and progressing the intervention, and determining when to discontinue intervention and physical therapy overall or to discharge the patient from care. The specific components of the intervention prescription include the intervention, its intensity (if applicable), duration, and frequency, as well as its course and progression. A problem-solving approach to patient care has become essential across health care professions, given the prohibitive cost of such care and the need for health care to be physiological, evidence-based, cost-effective, and ethically justifiable. As noninvasive practitioners, physical therapists need to evaluate their effectiveness in avoiding, reducing, or postponing the need for invasive care (i.e., drugs and surgery). Although these outcomes are exceptionally important, they all too often are underestimated in practice.