Chapter 5 Maximizing Children’s Health

Screening, Anticipatory Guidance, and Counseling

Periodicity

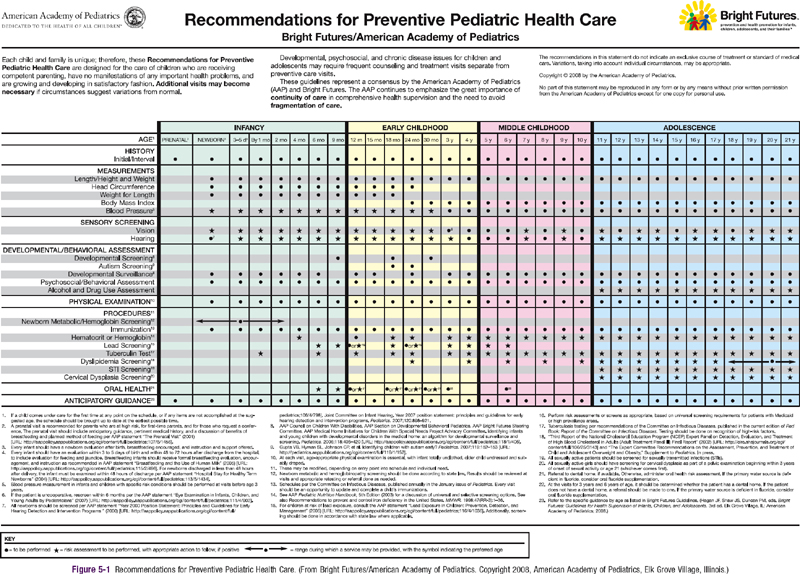

The frequency and content for well child care activities are derived from expert consensus, both from federal agencies and professional organizations such as the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and from evidence-based practice, when available. The Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care or Periodicity Schedule (Fig. 5-1) is a compilation of recommendations listed by age-based visits. It is intended to guide practitioners of pediatric primary care to perform certain services and make observations at age-specific visits.

Figure 5-1 Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care.

(From Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics.

Guidelines

Comprehensive guides for care of well infants, children, and adolescents have been developed, based on the Periodicity Schedule, which expand and further recommend how practitioners might accomplish the tasks outlined in the Periodicity Schedule. In the USA, the current guideline standard is The Bright Futures Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, 3rd Edition. These guidelines were developed by the AAP under the leadership of the Maternal Child Health Bureau of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in collaboration with the National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners, the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, Family Voices, and others. This subsumes previous guidelines and is consistent with the AAP and Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule (see Fig. 5-1).

Tasks of Well Child Care

The tasks of each well child visit include:

Office Intervention for Behavioral and Mental Health Issues

Twenty percent of primary care encounters with children are for a behavioral or mental health problem, or are sickness visits complicated by a mental health issue. Pediatricians need increased knowledge for diagnosis, treatment, and referral criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Chapter 30), depression (Chapter 24), anxiety (Chapter 23), and conduct disorder (Chapter 27), as well as an understanding of the pharmacology of the frequently prescribed psychotropic medications. Encouragement of behavioral change is also an important responsibility of the clinician. Motivational interviewing provides a structured approach that has been designed to help patients and parents identify the discrepancy between their desire for health and their behavioral choices. It also allows the clinician to use proven strategies that lead to a patient-initiated plan for change.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Community Health Services. The pediatrician’s role in community pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1999;103:1304-1307.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, Bright Futures Steering Committee. Recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1376.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Council on Children with Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, et al. Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics. 2006;118:405-420.

American Academy of PediatricsCouncil on Children with DisabilitiesJohnson CP, et al. Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120:1183-1215.

American Academy of Pediatrics, Division of Health Policy Research. Periodic survey of fellows #56: executive summary. Pediatricians’ provision of preventive care and use of health supervision guidelines. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; May 2004.

Bordley WC, Margolis PA, Stuart J, et al. Improving preventive service delivery through office systems. Pediatrics. 2001;108:E41.

Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Dong M, et al. Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: the adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:564-572.

Frankowski BL, Leader IC, Duncan PM. Strength-based interviewing. Adolesc Med. 2009;20:22-40.

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM, editors. Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents, ed 3, Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics, 2008.

Medical Home Initiatives for Children with Special Needs Project Advisory Committee, American Academy of Pediatrics. The medical home. Pediatrics. 2002;110:184-186.

Murphey DM, Hale K, Carney J, et al. Relationships of a brief measure of youth assets to health promoting and risk behaviors. J Adolesc Health. 2004;34:184-191.

National Business Group on Health. Investing in maternal and child health: an employer’s toolkit. (website) www.businessgrouphealth.org/benefitstopics/et_maternal.cfm Accessed May 9, 2009

Resnick MD. Resilience and protective factors in the lives of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2000;27(1):1-2.

Resnicow KD, DiIorio C, Soet JE, et al. Motivational interviewing in health promotion: it sounds like something is changing. Health Psychol. 2002;21:444-451.

5.1 Injury Control

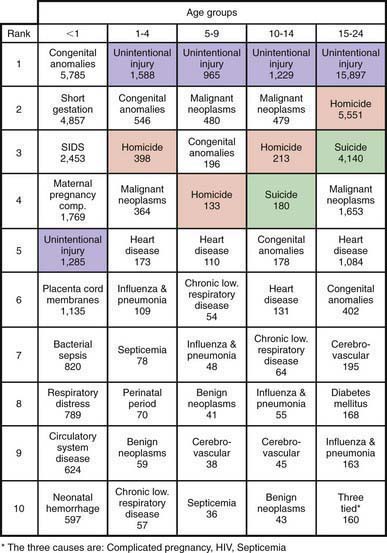

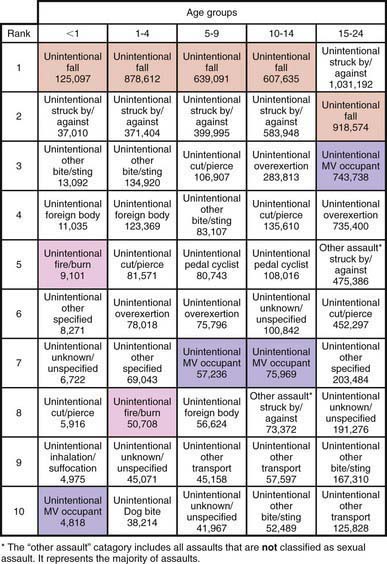

Injuries are the most common cause of death during childhood and adolescence beyond the 1st few mo of life and represent 1 of the most important causes of preventable pediatric morbidity and mortality (Figs. 5-2 and 5-3). The identification of risk factors for injuries has led to the development of successful programs for prevention and control. Strategies for injury prevention and control should be pursued by the pediatrician in the office, emergency department, hospital, and community setting.

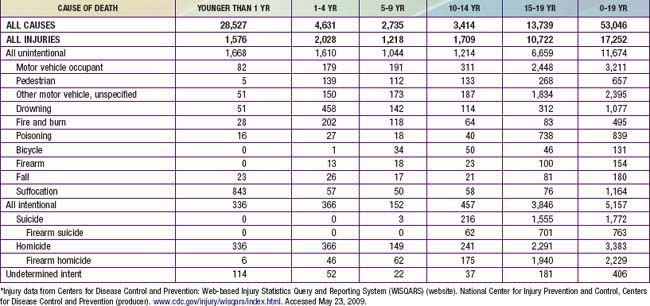

Figure 5-2 Ten leading causes of death by age group, USA, 2007.

(Modified from National Vital Statistics System, National Center for Health Statistics, CDC. Produced by Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC: 10 leading causes of death by age group, United States—2007 [PDF]. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/Death_by_Age_2007-a.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2010.)

(Modified from NEISS All Injury Program operated by the Consumer Product Safety Commission [CPSC]. Produced by Office of Statistics and Programming, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC: National estimates of the 10 leading causes of nonfatal injuries treated in hospital emergency departments, United States—2008 [PDF]. www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/pdf/Nonfatal_2008-a.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2010.)

Scope of the Problem

Mortality

In the USA, injuries cause 42% of deaths among 1-4 yr old children and 3 times more deaths than the next leading cause, congenital anomalies. For the rest of childhood and adolescence up to the age of 19 yr, 65% of deaths are due to injuries, more than all other causes combined. In 2006, injuries caused 17,252 deaths (21 deaths per 100,000) among individuals 19 yr old and younger in the USA (Table 5-1), resulting in more years of potential life lost than any other cause.

Drowning ranks 2nd overall as a cause of unintentional trauma deaths, with peaks in the preschool and later teenage years (Chapter 67). In some areas of the USA, drowning is the leading cause of death from trauma for preschool-aged children. The causes of drowning deaths vary with age and geographic area. In young children, bathtub and swimming pool drowning predominate, whereas in older children and adolescents, drowning occurs predominantly in natural bodies of water while the victim is swimming or boating.

Fire and burn deaths account for 4% of all unintentional trauma deaths and 8% in those younger than 5 yr of age (Chapter 68). Most of these are due to house fires; deaths are caused by smoke inhalation and asphyxiation rather than severe burns. Children and the elderly are at greatest risk for these deaths because of difficulty in escaping from burning buildings.

Homicide is the 3rd leading cause of injury death in children 1-4 yr of age and the 2nd leading cause of injury death in adolescents (15-19 yr old). Homicide in the pediatric age group falls into 2 patterns: infantile and adolescent. Infantile homicide involves children younger than the age of 5 yr and represents child abuse (Chapter 37). The perpetrator is usually a caretaker; death is generally the result of blunt trauma to the head and/or abdomen. The adolescent pattern of homicide involves peers and acquaintances and is due to firearms in >80% of cases. The majority of these deaths involve handguns. Children between these 2 age groups experience homicides of both types.

Suicide is rare in children younger than age 10 yr; only 1% of all suicides occur in children younger than age 15 yr. The suicide rate increases markedly after the age of 10 yr, with the result that suicide is now the 3rd leading cause of death for 15-19 yr olds. Native American teenagers are at the highest risk, followed by white males; black females have the lowest rate of suicide in this age group. Approximately one half of teenage suicides involve firearms (Chapter 25).

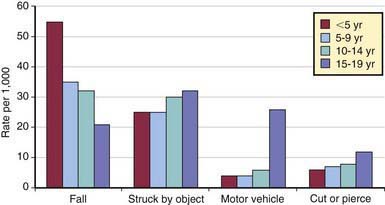

Nonfatal Injuries

The distribution of these nonfatal injuries is very different from that of fatal trauma (Fig. 5-4). Falls are the leading cause of both emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Bicycle-related trauma is the most common type of sports and recreational injury, accounting for approximately 300,000 emergency department visits annually. Nonfatal injuries, such as anoxic encephalopathy from near-drowning, scarring and disfigurement from burns, and persistent neurologic deficits from head injury, may be associated with severe morbidity, leading to substantial changes in the quality of life for victims and their families.

Principles of Injury Control

Efforts to control injuries include education or persuasion, changes in product design, and modification of the social and physical environment. Efforts to persuade individuals, particularly parents, to change their behaviors have constituted the greater part of injury control efforts. Speaking with parents specifically about using child car seat restraints and bicycle helmets, installing smoke detectors, and checking the tap water temperature is likely to be more successful than offering well-meaning but too-general advice about supervising the child closely, being careful, and “childproofing” the home. This information should be geared to the developmental stage of the child and presented in moderate doses in the form of anticipatory guidance at well-child visits. Important topics to discuss at each developmental stage are shown in Table 5-2.

Table 5-2 INJURY PREVENTION TOPICS FOR ANTICIPATORY GUIDANCE BY THE PEDIATRICIAN

NEWBORN

INFANT

TODDLER AND PRESCHOOLER

PRIMARY SCHOOL CHILD

MIDDLE SCHOOL CHILD

HIGH SCHOOL AND OLDER ADOLESCENT

The most successful injury prevention strategies generally are those involving changes in product design, as shown in Table 5-3. These passive interventions protect all individuals in the population, regardless of cooperation or level of skill, and are likely to be more successful than active measures that require repeated behavior change by the parent or child. However, for some types of injuries, effective passive interventions are not available or feasible; we must rely heavily on attempts to change the behavior of individuals. Turning down the water heater temperature, installing smoke detectors, and using child-resistant caps on medicines and household products are examples of effective product modifications. Many interventions require both active and passive measures. Smoke detectors provide passive protection when fully functional, but behavior change is required to ensure annual battery changes and proper testing.

| PRODUCT MODIFICATION | ENVIRONMENTAL MODIFICATION | EDUCATION |

|---|---|---|

| Child-resistant caps | Cabinet locks | Anticipatory guidance |

| Airbags | Roadway design | Public service announcements |

| Fire-safe cigarettes | Smoke detectors | School safety programs |

Risk Factors for Childhood Injuries

Mechanisms of Injury

Motor Vehicle Injuries

Occupants

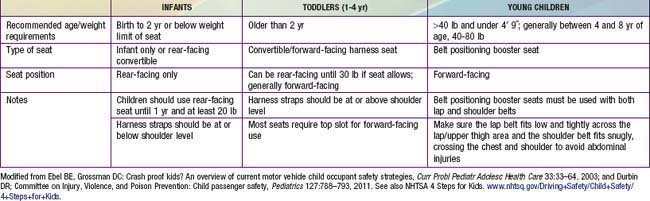

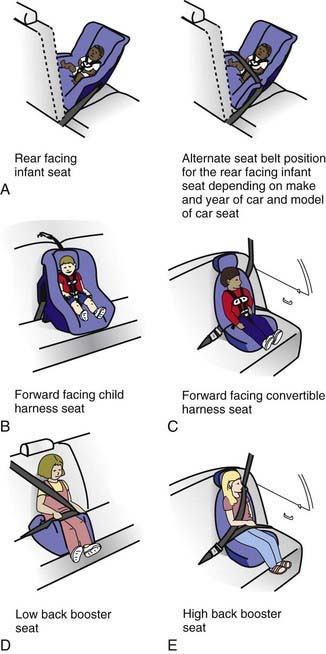

Injuries to passenger vehicle occupants are the predominant cause of motor vehicle deaths among children and adolescents, with the exception of the 5-9 yr old group, in whom pedestrian injuries make up the largest proportion. The peak injury and death rate for both males and females in the pediatric age group occurs between 15 and 19 yr of age (see Table 5-1). Proper restraint use in vehicles is the single most effective method for preventing serious or fatal injury. The recommended restraints at different ages are shown in Table 5-4. Examples of car safety seats are noted in Figure 5-5.

(From Ebel BE, Grossman DC: Crash proof kids? An overview of current motor vehicle child occupant safety strategies, Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care 33:33–64, 2003. Source: NHTSA; graphics courtesy of Transportation Safety Training Center, Virginia Commonwealth University: Types of child safety seats [website]. www.nhtsa.dot.gov/people/injury/childps/safetycheck/typeseats/index.htm. Accessed November 1, 2010.)

A detailed guide and list of acceptable devices is available from the American Academy of Pediatrics (www.healthychildren.org/English/safety-prevention/on-the-go/pages/Car-Safety-Seats-Information-for-Families-2010.aspx). Children weighing <20 lb may use an infant seat or be placed in a convertible infant-toddler child restraint device. Infants younger than 2 yr or if less than manufacturer’s weight limit should be placed in the rear seat facing backward; older toddlers and young children can be placed in the rear seat in a forward-facing child harness seat, until it is outgrown. Emphasis must be placed on the correct use of these seats, including placing the seat in the right direction, routing the belt properly, and ensuring that the child is buckled into the seat correctly. Government regulations have made the fit between car seats and the car easier, quicker, and less prone to error. Children younger than age 13 yr should never sit in the front seat, especially if an airbag is present. Inflating airbags can be lethal to infants in rear-facing seats and to small children in the front passenger seat.

Teenage Drivers

Alcohol use is a major cause of motor vehicle trauma among adolescents. The combination of inexperience in driving and inexperience with alcohol is particularly dangerous. Approximately 20% of all deaths from motor vehicle crashes in this age group are the result of alcohol intoxication, with impairment of driving seen at blood alcohol concentrations as low as 0.05 g/dL. Approximately 30% of adolescents report riding with a driver who had been drinking and about 10% report driving after drinking. All states have adopted a zero tolerance policy, which defines any measurable alcohol content as legal intoxication, to adolescent drinking while driving. All adolescent motor vehicle injury victims should have their blood alcohol concentration measured in the emergency department and be screened for high-risk alcohol use with a validated screening test (such as the CRAFFT or AUDIT screening tools) to identify those with alcohol abuse problems (Chapter 108.1). Individuals who have evidence of alcohol abuse should not leave the emergency department or hospital without plans for appropriate alcohol abuse treatment. Interventions for problem drinking can be effective in decreasing the risk of subsequent motor vehicle crashes. Even brief interventions in the emergency department using motivational interviewing can be successful in decreasing adolescent problem drinking.

Psychosocial Consequences of Injuries

Many children and their parents have substantial psychosocial sequelae from trauma. Studies in adults indicate that 10-40% of hospitalized injured patients will have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; Chapter 23). Among injured children involved in motor vehicle crashes, 90% of families will have symptoms of acute stress disorder after the crash, although the diagnosis of acute stress disorder is not predictive of later PTSD. Standardized questionnaires that collect data from the child, the parents, and the medical record at the time of initial injury can serve as useful screening tests for later development of PTSD. Early mental health intervention, with close follow-up, is important for the treatment of PTSD and for minimizing its effect on the child and family.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement—role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention? Pediatrics. 2009;124:393-402.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention, Committee on Adolescence. The teen driver. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2570-2581.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Children in pickup trucks. Pediatrics. 2000;106:857-859.

Barrios LC, Davis MK, Kann L, et al. School health guidelines to prevent unintentional injuries and violence. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-22):1-73.

Bernard SJ, Paulozzi LJ, Wallace LJD. Fatal injuries among children by race and ethnicity—United States, 1999–2002. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2007;56:1-16.

Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LRJr, et al. 2007 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System (NPDS): 25th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2008;46(10):927-1057.

Brenner RA, Taneja GS, Haynie DL. Association between swimming lessons and drowning in childhood: a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.. 2009;163:203-210.

Bull MJ, Engle WA, Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention and Committee on Fetus and Newborn, et al. Safe transportation of preterm and low birth weight infants at hospital discharge. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1424-1429.

Bunn F, Colloer T, Frost C, et al: Area-wide traffic calming for preventing traffic related injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1):CD003110, 2003.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Unintentional strangulation deaths from the “choking game” among youths aged 6–19 years—United States, 1995–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57(6):141-144.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Injuries resulting from car surfing—United States, 1990–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1121-1124.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Illnesses and injuries related to total release foggers—eight states, 2001–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:1125-1129.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Motor vehicle-related death rates—United States, 1999–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:161-165.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School-associated student homicides—United States, 1992–2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:33-36.

Chadwick DL, Bertocci G, Castilo E, et al. Annual risk of death resulting from short falls among young children: less than 1 in 1 million. Pediatrics. 2008;121:1213-1224.

Cheng TL, Haynie D, Brenner R, et al. Effectiveness of a mentor-implemented, violence prevention intervention for assault-injured youths presenting to the emergency department: results of a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2008;122:938-946.

Chiavello C, Christoph R, Bond G. Infant walker related injuries: a prospective study of severity and incidence. Pediatrics. 1994;93:974-976.

Committee on Injury Prevention and Poison Prevention Committee on Community Health Services. Prevention of agricultural injuries among children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2001;108:1016-1019.

Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention Committee on Adolescence. The teen driver. Pediatrics. 2006;118:2571-2581.

Committee on Sports Medicine and Fitness and Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention, American Academy of Pediatrics. Swimming programs for infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2000;105:868-870.

Cummings P, Koepsell TD, Rivara FP, et al. Airbags and passenger fatality according to passenger age and restraint use. Epidemiology. 2002;13:525-532.

Dowswell T, Towner E. Social deprivation and the prevention of unintentional injury in childhood: a systematic review. Health Educ Res. 2002;7:221-237.

Du W, Hayen A, Bilston L, et al. Association between different restraint use and rear-seated child passenger fatalities. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162:1085-1089.

Duperrex O, Roberts I, Bunn F. Safety education of pedestrians for injury prevention: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2002;324:1129.

Durbin DR, Elliott MR, Winston FK. Belt-positioning booster seats and reduction in risk of injury among children in vehicle crashes. JAMA. 2003;289:2835-2840.

Evans CAJr, Fielding JE, Brownson RC, et al. Motor vehicle occupant injury: strategies for increasing use of child safety seats, increasing use of safety belts, and reducing alcohol-impaired driving. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2001;50(RR-7):1-14.

Farrington DP, Welsh BC. Saving children from a life of crime: early risk factors and effective interventions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Greenberg JM. The challenge of care safety seats. J Pediatr. 2007;150:215-216.

Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional firearm injuries. JAMA. 2005;293:740-741.

Hahn R, Fuqua-Whitley D, Wethington H, et al. The effectiveness of universal school-based programs for the prevention of violent and aggressive behavior: a report on recommendations of the Task Force on Community Preventive Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-7):1-12.

Huang P, Kallan MJ, O’Neil J, et al. Children with special health care needs: patterns of safety restraint use, seating position, and risk of injury in motor vehicle crashes. Pediatrics. 2009;123:518-523.

Johnston BD, Rivara FP, Drowsch RM, et al. Behavior change counseling in the emergency department to reduce injury risk: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2002;110:267-274.

Karch DL, Dahlberg LL, Patel N, et al. Surveillance for violent deaths—National Violent Death Reporting System, 16 states, 2006. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2009;58(1):1-44.

Kellermann AL, Rivara FP, Somes G, et al. Suicide in the home in relation to gun ownership. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:467-472.

Kellum K, Creek A, Dawkins R, et al. Age-related patterns of injury in children involved in all-terrain vehicle accidents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28:854-858.

Kirkwood G, Pollock A. Preventing injury in childhood. BMJ. 2008;336:1388-1389.

Krug EG. Injury surveillance is key to preventing injuries. Lancet. 2004;364:1563-1566.

The Lancet. Is exposure to media violence a public-health risk? Lancet. 2008;371:1137.

The Lancet. Gun violence and public health. Lancet. 2007;369:1403.

The Lancet. On the road: accidents that should not happen. Lancet. 2007;369:1319.

Macpherson A, Spinks A: Bicycle helmet legislation for the uptake of helmet use and prevention of head injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3):CD005401, 2008.

Newgard CD, Lewis RJ. Effects of child age and body size on serious injury from passenger air-bag presence in motor vehicle crashes. Pediatrics. 2005;115:1579-1585.

Norton C, Nixon J, Sibert JR. Playground injuries to children. Arch Dis Child. 2004;89:103-108.

Parkin PC, Howard AW. Advances in the prevention of children’s injuries: an examination of four common outdoor activities. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20(6):719-723.

Peden M, Oyegbite K, Ozanne-Smith J, et al, editors. World report on child injury prevention. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

Shope JT. Graduated driver licensing: review of evaluation results since 2002. J Safety Res. 2007;38:165-175.

Spirito A, Monti PM, Barnett NP, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J Pediatr. 2004;145:396-402.

Thompson DC, Nunn ME, Thompson RS, et al. Effectiveness of bicycle helmets in preventing serious facial injury. JAMA. 1996;276:1974-1975.

Tremblay RE, Nagin DS, Seguin JR, et al. Physical aggression during early childhood: trajectories and predictors. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e43-e50.

Walton M, Cunningham R, Xue Y, et al. Internet referrals for adolescent violence prevention: an innovative mechanism for inner-city emergency departments. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43:309-312.

Wesson DE, Stephens D, Lam K, et al. Trends in pediatric and adult bicycling deaths before and after passage of a bicycle helmet law. Pediatrics. 2008;122:605-610.

Williams AF. Licensing age and teenage driver crashes: a review of the evidence. Traffic Inj Prev. 2009;10:9-15.

Winston FK, Kallan MJ, Elliott MR, et al. Risk of injury to child passengers in compact extended-cab pickup trucks. JAMA. 2002;287:1147-1152.

Winston FK, Kassam-Adams N, Garcia-Espana F, et al. Screening for risk of persistent posttraumatic stress in injured children and their parents. JAMA. 2003;290:643-649.

Wolfe DA, Crooks C, Jaffe P, et al. A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:692-699.

Ybarra ML, Diener-West M, Markow D, et al. Linkages between internet and other media violence with seriously violent behavior by youth. Pediatrics. 2008;122:929-937.