Maxillofacial Trauma

General Treatment

1. Perform a primary survey, paying particular attention to airway compromise from aspiration of blood, avulsed teeth or dental appliance, direct trauma and swelling, or a retrusive tongue secondary to a mobile mandibular fracture. The most important part of care for maxillofacial trauma is maintenance of a clear airway. If the airway is threatened by edema or inability of the patient to keep the airway clear, early intubation is recommended. Cricothyrotomy (see Chapter 10) may be necessary.

a. Remove any loose material (teeth, clots, soft tissue, foreign material) from the oropharynx to clear the airway.

b. Note any deformity or asymmetry of the facial structures, which may indicate underlying bone fracture.

c. Enophthalmos may be one sign that an orbital blowout fracture is present.

d. Look for malocclusion or a step-off in the teeth as an indication of mandibular or maxillary fracture.

e. Observe the position and integrity of the nasal septum. If the septum is bulging on one side into the nasal cavity, it could indicate a septal hematoma. A septal hematoma can be drained in the field by making a small incision into the septum with a safety pin or point of a knife, allowing the blood to drain out.

f. Examine soft tissue injuries, looking for foreign bodies, including avulsed teeth.

g. Test motor and sensory function by checking for sensation on each side of the face and by having the patient wrinkle the forehead, smile, bare the teeth, and close the eyes tightly.

h. Gently palpate the facial structures, noting areas of tenderness, bony defects, crepitus, and false motion.

i. Test dental integrity by grasping the front and bottom anterior teeth and checking for motion.

j. If the patient is unconscious but breathing well and shows no sign of hemorrhaging into the airway, you can use an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway to ensure airway patency.

2. Anticipate cervical spine trauma, and immobilize the spine if indicated (see Box 12-5). If cervical spine injury is possible and airway protection is required, perform endotracheal intubation or cricothyrotomy while maintaining manual cervical spine immobilization.

3. Control bleeding with direct pressure.

a. For intraoral bleeding, have the patient bite firmly on a gauze pad.

b. For bleeding from the nose, squeeze and hold the nostrils together, use nasal packing, or deploy a Foley catheter (see Nasal Fracture and Epistaxis, later).

4. Treat shock (see Chapter 13).

5. Recover any completely avulsed teeth or other tissues, irrigate with normal saline solution, and transport in a saline-soaked gauze sponge.

Disorders

Signs and Symptoms

1. Lacrimal drainage system: injury confirmed if a probe inserted into the punctum at the medial canthus of the eye emerges from the laceration

2. Parotid duct: injury suspected if there is buccal nerve paralysis or leakage from the wound when Stensen’s duct is irrigated with saline solution or water

3. Facial nerve: asymmetry when the patient moves the eyebrows, eyelids, and mouth

Treatment

1. Wash and irrigate wounds copiously with soap and clean water or sterile saline.

2. Remove any foreign debris and devitalized tissue

3. Local anesthesia and primary suture closure may be appropriate in the field for small, minimally contaminated lacerations (see Chapter 20).

4. Lacerations involving the salivary ducts, facial nerves, or complicated facial structures, such as the vermilion border of the lips, nasal alar rims, or auricular helical rims of the ears, should be repaired by experienced providers or cleaned and bandaged for delayed closure following evacuation.

5. Clean, simple, and uncontaminated facial wounds less than 6 hours old may be appropriate for skin glue or adhesive tape closure.

Midface (Le Fort) Fractures

1. Tenderness, ecchymosis, and swelling over fracture site

2. Le Fort 1 fracture—facial edema and mobility of the hard palate and upper teeth

3. Le Fort II fracture—facial edema, telecanthus, subconjunctival hemorrhage, mobility of the maxilla at the nasofrontal suture, epistaxis, and possible cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea

4. Le Fort III fracture—massive edema with facial elongation and flattening. An anterior open bite may be present because of posterior and inferior displacement of the facial skeleton. Movement of the entire upper dental arch or face on grasping the alveolar process and anterior teeth between the thumb and forefinger and rocking gently back and forth, epistaxis, and cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea

Treatment of Mandibular or Midface Fracture

1. Elevate the patient’s head to reduce bleeding and swelling.

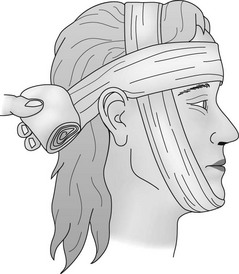

2. Stabilize the site with bandages (Fig. 17-1).

3. Control epistaxis (see later).

4. Evacuate the patient immediately.

5. Administer antibiotic prophylaxis with phenoxymethyl penicillin or clindamycin if penicillin allergic (see Appendix H).

Nasal Fracture and Epistaxis

Treatment

Treatment of epistaxis depends on whether the source is anterior or posterior.

1. If a septal hematoma is present, make a small incision through the mucosa and perichondrium to allow drainage. Pack the anterior nasal cavity (see later) to prevent reaccumulation of blood.

a. If bleeding cannot be controlled by firmly pinching the nostrils against the septum for a full 10 minutes, nasal packing may be necessary. Insert a piece of cotton or gauze soaked with a vasoconstricting agent, such as oxymetazoline hydrochloride 0.05% (Afrin) or phenylephrine hydrochloride (Neo-Synephrine), into the nose, and leave it in place for 5 to 10 minutes. Next, layer-pack petrolatum-impregnated gauze or strips of a nonadherent dressing into the nose so that both ends of the gauze remain outside the nasal cavity to lessen the likelihood that the patient might inadvertently aspirate the packing.

b. To pack an adult’s nasal cavity completely, at least 3 to 4 feet (approximately 1 m) of 0.6-cm ( -inch) material is required to fill the nasal cavity and tamponade the bleeding site.

-inch) material is required to fill the nasal cavity and tamponade the bleeding site.

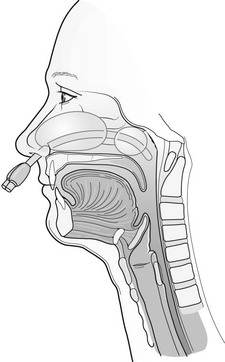

c. Expandable packing materials, such as Weimert Epistaxis Packing, Epi-Max, Rapid Rhino, or Rhino Rocket balloon catheters, are available for treatment of anterior, posterior, or both anterior and posterior epistaxis (Fig. 17-2). They should be used only if compression and simple anterior packing with gauze fails to control bleeding. Once placed, nasal balloons should remain in place for 1 to 3 days and patients should be started on prophylactic antibiotics, such as cephalexin, erythromycin, or amoxicillin, to prevent sinusitis and toxic shock syndrome (see Appendix H).

FIGURE 17-2 Commercially available nasal packing balloons are lightweight, inexpensive, and easy to deploy.

d. A tampon or balloon tip from a Foley catheter can also be used as improvised packing.

a. Use a 14- to 16-French Foley catheter with a 30-mL balloon to tamponade the site. The catheter should be lubricated with either petrolatum or a water-based lubricant. Insert the catheter through the nasal cavity into the posterior pharynx. Next, inflate the balloon with 10 to 15 mL of water and gently draw it back into the posterior nasopharynx until resistance is met. Inflation should be done slowly and should be stopped if painful. Secure the catheter firmly to the patient’s forehead with several strips of tape. Finally, pack the anterior nose in front of the catheter balloon with gauze as described earlier.

b. Alternatively, use a commercially available balloon catheter, such as the Epi-Max or Rapid Rhino, specifically designed to control both posterior and anterior epistaxis.

c. Administer a prophylactic antibiotic, such as cephalexin, erythromycin, or amoxicillin (see Appendix H).

Foreign Body in the Nose

Treatment

1. Attempt to visualize the object and extract it. Do not proceed if you find the object moving deeper into the nostril or the patient is in extreme pain. Leave the object in place, and prepare the patient for evacuation.

2. If the patient develops a fever, administer an antibiotic, such as cephalexin, erythromycin, or amoxicillin (see Appendix H).