Maternal medicine

Introduction

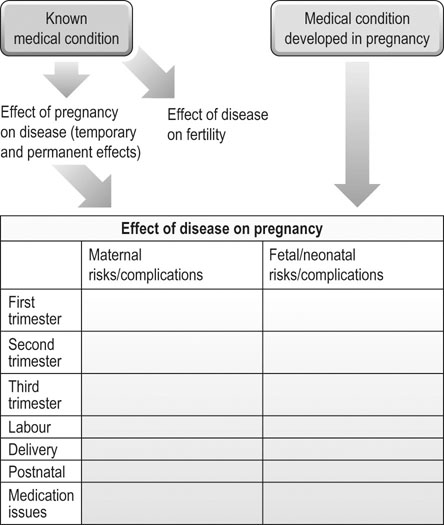

Whether a woman is known to have a medical condition prior to pregnancy or develops one within pregnancy, the key to successful management is to have a framework to ensure that all the implications of the condition are considered (Fig. 9.1). This enables robust pregnancy plans to be made whether a disease is common or rare. Multi-disciplinary and multi-professional team-working are also essential elements in caring for these women.

Minor complaints of pregnancy

Abdominal pain

• stretching of the abdominal ligaments and muscles

It is important to differentiate physiological abdominal pain from pathological causes in women with severe, atypical or recurrent pain. These include:

• early pregnancy problems such as ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage

• gynaecological causes such as ovarian torsion

• surgical causes such as appendicitis and pancreatitis

• later obstetric causes such as placental abruption and labour.

Social causes, particularly domestic abuse, should be considered in women who present with recurrent episodes of abdominal pain where organic pathology has been excluded.

Heartburn

• other causes of chest pain such as angina, myocardial infarction and muscular pain

• causes of upper abdominal pain that can mimic reflux, for example, pre-eclampsia, acute fatty liver of pregnancy and gallstones.

Conservative management includes dietary advice to avoid spicy and acidic foods and to avoid eating just prior to bed. Symptoms can be improved by changing sleeping position to a more upright posture. If conservative measures are not successful antacids are safe in pregnancy and can be used at any time. Histamine-receptor blockers, such as ranitidine, and proton pump inhibitors have a good safety profile in pregnancy and can be used if antacids alone are insufficient to improve symptoms.

Medical problems arising in pregnancy

Anaemia

Aetiology

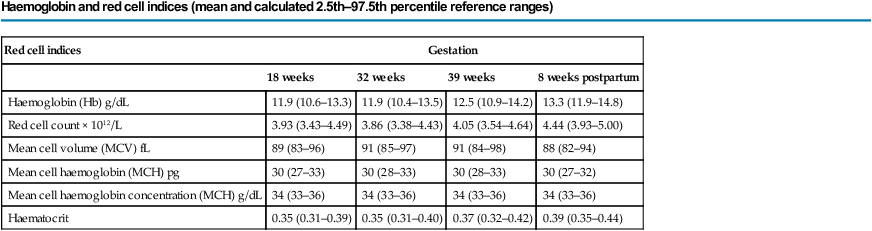

Pregnancy causes many changes in the haematological system, including an increase in both plasma volume and red cell mass; the former is greater than the latter with the result that a ‘physiological anaemia’ often occurs. There is an increased iron and folate demand to facilitate both the increase in red cell mass and fetal requirements, which is not always met by maternal diet. Iron deficiency anaemia is thus a common condition encountered in pregnancy, particularly in the third trimester. Table 9.1 shows the changes of haemoglobin and red cell parameters in normal pregnancy.

Table 9.1

Haemoglobin and red cell indices (mean and calculated 2.5th–97.5th percentile reference ranges)

Haemoglobin and red cell indices (mean and calculated 2.5th–97.5th percentile reference ranges)

| Red cell indices | Gestation | |||

| 18 weeks | 32 weeks | 39 weeks | 8 weeks postpartum | |

| Haemoglobin (Hb) g/dL | 11.9 (10.6–13.3) | 11.9 (10.4–13.5) | 12.5 (10.9–14.2) | 13.3 (11.9–14.8) |

| Red cell count × 1012/L | 3.93 (3.43–4.49) | 3.86 (3.38–4.43) | 4.05 (3.54–4.64) | 4.44 (3.93–5.00) |

| Mean cell volume (MCV) fL | 89 (83–96) | 91 (85–97) | 91 (84–98) | 88 (82–94) |

| Mean cell haemoglobin (MCH) pg | 30 (27–33) | 30 (28–33) | 30 (28–33) | 30 (27–32) |

| Mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCH) g/dL | 34 (33–36) | 34 (33–36) | 34 (33–36) | 34 (33–36) |

| Haematocrit | 0.35 (0.31–0.39) | 0.35 (0.31–0.40) | 0.37 (0.32–0.42) | 0.39 (0.35–0.44) |

(Reproduced with permission from Shepard MJ, Richards VA, Berkowitz RL, et al (1982) An evaluation of two equations for predicting fetal weight by ultrasound. Am J Obstet Gynecol 142:47–54. © 1982 Elsevier.)

Risk factors

Pre-pregnancy risk factors are those associated with chronic anaemia:

• iron deficiency secondary to poor diet

• short interval between pregnancies

• presence of anaemic conditions, such as sickle cell disease, thalassaemia and haemolytic anaemia.

Risk factors within pregnancy include multiple pregnancy due to the increased iron demand in multiple pregnancy scenarios.

Gestational diabetes

Risk factors

Risk factors are the same as those for type 2 diabetes and are listed in Box 9.1. This list is taken from the NICE Clinical Guideline ‘Diabetes in pregnancy’ (2008). The Guideline only recommends that some of the risk factors should be used for screening in practice. The presence of one or more of these risk factors should lead to the offer of a75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). However, many clinicians feel that the presence of any risk factor, rather than a subset, should trigger the offer of an OGTT.

Clinical features and diagnosis

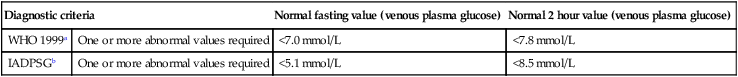

Gestational diabetes may be asymptomatic. As such, a screening programme needs to be in place that can either be universal or selective. Most units prefer a selective approach for practical and financial reasons. Selective screening is offered to the at-risk groups listed in Box 9.1. As described above, screening is by an 75 g OGTT at 28 weeks, or if very high risk, early in the second trimester and then repeated at 28 weeks (if normal at the first test). In the OGTT, a fasting glucose level is first measured, then a 75 g loading dose of glucose is given and a further glucose level taken at 2 hours post-sugar load. There is an ongoing debate as to the levels of glucose at which gestational diabetes should be diagnosed. Table 9.2 indicates the two most commonly used diagnostic criteria.

Table 9.2

Diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes using a 75g oral glucose tolerance test

| Diagnostic criteria | Normal fasting value (venous plasma glucose) | Normal 2 hour value (venous plasma glucose) | |

| WHO 1999a | One or more abnormal values required | <7.0 mmol/L | <7.8 mmol/L |

| IADPSGb | One or more abnormal values required | <5.1 mmol/L | <8.5 mmol/L |

Comment: In a given population, use of the IADPSG criteria results in more diagnoses of ‘gestational diabetes’ than using the WHO criteria. WHO, World Health Organization; IADPSG, International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups.

aWorld Health Organization: Definition, Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus and its Complications: Report of a WHO Consultation. Part 1: Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1999.

bMetzger, B.E., Gabbe, S.G., Persson, B., et al. International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:676–682.

Implications on pregnancy

Gestational diabetes is predominantly a disease of the third and sometimes second trimester (Table 9.3). In the mother, the presence of gestational diabetes increases the risk of recurrent infections and of pre-eclampsia developing. For the fetus there is increased risk of polyhydramnios and macrosomia, the latter being related to the degree of glucose control. There is an increased risk of stillbirth. Considering birth, women with gestational diabetes are more likely to have an induction of labour. If vaginal birth occurs, shoulder dystocia, an instrumental birth and extended perineal tears are more common. Women with diabetes are more likely to have a caesarean section. Babies are more likely to need admission to the neonatal unit. They are at increased risk of neonatal hypoglycaemia due to the relative over-activity of the fetal pancreas in utero. This is less likely to occur if maternal blood sugars are well controlled around the time of birth. Maternal glucose readily crosses the placenta whilst insulin does not.

Table 9.3

Effect of gestational diabetes on pregnancy

| Maternal risks/complications | Fetal/neonatal risks/complications | |

| First trimester | – | – |

| Second trimester Third trimester |

Pre-eclampsia Recurrent infections |

Macrosomia Polyhydramnios Stillbirth |

| Labour | Induction of labour Poor progress in labour |

|

| Delivery | Instrumental birth Traumatic delivery Caesarean section |

Shoulder dystocia |

| Postnatal | Neonatal hypoglycaemia Neonatal unit admission Respiratory distress syndrome Jaundice |

|

| Longer term | Type 2 diabetes later in life | Obesity and diabetes in childhood and later life |

Whilst for the majority of women gestational diabetes will resolve post-pregnancy, in some women this diagnosis is the unmasking of type 2 diabetes and diabetic care will need to continue. Women who have had gestational diabetes remain at higher risk of developing type 2 diabetes later in life. For the babies, fetal programming effects increase the risk of obesity and diabetes in later childhood.

Pre-existing medical conditions and pregnancy

Renal disease in pregnancy

Implications of pregnancy on the disease

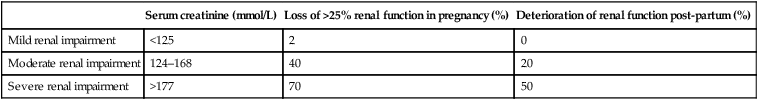

In women with chronic renal disease, pregnancy can cause a deterioration of renal function. Mostly this will recover after the end of the pregnancy, but for some women this will lead to a permanent reduction in renal functioning and a shorter time to end stage renal failure. The likelihood of renal deterioration depends on baseline creatinine as shown in Table 9.4.

Table 9.4

Maternal renal function and chronic renal disease in pregnancy

| Serum creatinine (mmol/L) | Loss of >25% renal function in pregnancy (%) | Deterioration of renal function post-partum (%) | |

| Mild renal impairment | <125 | 2 | 0 |

| Moderate renal impairment | 124–168 | 40 | 20 |

| Severe renal impairment | >177 | 70 | 50 |

(Data from Williams D, Davidson J. Chronic kidney disease in pregnancy. Br Med J 2008;336:211–215.)

Diabetes mellitus

Implications of pregnancy on the disease

• The anti-insulin effects of placental hormones (see gestational diabetes, above) result in a larger insulin requirement in pregnancy. Women have to increase their insulin requirements up to threefold to combat this. These changes revert to the prepregnancy state within hours of birth.

• Vomiting in early pregnancy can complicate diet and medication balance.

• Pregnancy can reduce the ‘warning signs’ of hypoglycaemia.

• In women with complications of diabetes, such as retinopathy and nephropathy, pregnancy can accelerate the progress of these complications.

Implications of the disease on pregnancy (Table 9.5)

Table 9.5

Risks of pre-existing diabetes in pregnancy

| Maternal concerns | Fetal/neonatal concerns | |

| First trimester | Increased insulin requirements | Miscarriage Fetal abnormality |

| Second trimester Third trimester |

Pre-eclampsia Recurrent infections Worsening retinopathy if vascular disease |

Macrosomia Polyhydramnios Stillbirth Growth restriction |

| Labour | Induction of labour Poor progress in labour |

Preterm delivery |

| Delivery | Instrumental birth Birth trauma caesarean section |

Shoulder dystocia |

| Postnatal | Return to pre-pregnancy control within hours of birth | Neonatal hypoglycaemia Neonatal unit admission Respiratory distress syndrome Jaundice |

| Longer term | – | Diabetes in childhood (2–3 % if mother has type 1; 10–15 % if mother has type 2) |

Obesity

Implications of obesity on pregnancy (Table 9.6)

Table 9.6

| Maternal risks/complications | Fetal/neonatal risks/complications | |

| First trimester | Venous thromboembolism | Miscarriage Fetal abnormality |

| Second trimester Third trimester |

Pre-eclampsia Gestational diabetes Venous thromboembolism |

Macrosomia Stillbirth Difficulty with fetal assessment |

| Labour | Induction of labour Poor progress in labour |

– |

| Delivery | Instrumental birth Traumatic birth Caesarean section Anaesthetic complications (difficulties with intubation or epidural insertion) |

Shoulder dystocia |

| Postnatal | Postpartum haemorrhage Venous thromboembolism |

Neonatal unit admission Neonatal death |

| Longer term | – | Childhood obesity Juvenile diabetes |

Cardiac disease

Management

Although the New York Heart Association classification provides some information about possible prognosis (Box 9.2) care plans should be individualized. Antenatally, stressors such as anaemia and infection should be minimized. Medication may need to be altered in some women and anticoagulation may also be required. Fetal surveillance may include serial growth scans and Doppler measurements as well as screening for cardiac defects. Maternal surveillance may involve regular echocardiograms.