CHAPTER 34 Mastopexy after Implant Removal

Preoperative Assessment (Table 34.1)

There are several important aspects of the preoperative assessment that will guide one’s operative plan. As shown in Table 34.2, it is important to consider the degree of ptosis present – patients with grade 2 or 3 ptosis should be considered for mastopexy after explantation (Table 34.3). One must also consider the patient’s skin tone, as a patient with loose, inelastic skin and multiple striae is likely to require mastopexy in order to preserve favorable breast aesthetics. An accurate assessment of the native breast parenchymal volume and distribution will also weigh in one’s decision regarding mastopexy after explantation. For example, a woman with a small amount of breast tissue will likely have an accentuation of breast ptosis and a loss of superior pole fullness after explantation, and will often require mastopexy to preserve a favorable shape. It is also important to evaluate for potential breast asymmetries, as such differences may actually be masked by augmentation. Asymmetry after explantation may also be present in the patient who had previous problems with implant infection, capsular contracture, or perhaps required multiple previous implant revisions. Lastly, one must evaluate the patient’s own sense of her breast aesthetics, particularly with regard to the patient’s acceptance of visible mastopexy scars on the breast.

Table 34.2 Degrees of breast ptosis

| Grade 1 – minor ptosis | Nipple is positioned at the inframammary fold but above the lower contour of the gland and skin brassiere. |

| Grade 2 – moderate ptosis | Nipple lies below the level of the fold but remains above the lower contour of the breast and skin brassiere. |

| Grade 3 – major ptosis | Nipple lies below the level of the fold and at the lower contour of the breast and skin brassiere. |

| Pseudoptosis | Characterized by a hypoplastic breast in which the full lower quadrants appear to have descended while the nipple remains above the inframammary fold. |

| Glandular ptosis | Characterized by descent of the lower breast quadrants with retention of the nipple at its normal level. |

Adapted from Regnault P. Ptosis, asymmetry, tubular breast, and congenital anomalies. In: Owsley JQ, Peterson RA, editors. Symposium on aesthetic surgery of the breast. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1978.

Table 34.3 Factors predictive of need for mastopexy after explantation

| Favorable | Unfavorable |

|---|---|

| Minimal ptosis (grade 1) | Moderate to severe ptosis (grade 2–3) |

| Excellent skin tone | Poor skin tone, striae |

| Dense/adequate breast tissue (>4 cm thick) | Minimal breast tissue (<4 cm thick) |

| Modest augmentation | Large augmentation |

Operative Technique

Patient markings

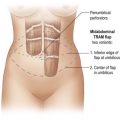

The patient should be marked in a standing position, noting the sternal notch, breast meridian, inframammary fold (IMF), and the new position of the nipple–areola complex. For the patient with mild ptosis and favorable breast characteristics, a short scar vertical mastopexy will often be appropriate. As the amount of skin to be resected will often change after implant removal, we favor a tailor tacking approach in the sitting position after the implant has been removed. For patients with moderate to severe ptosis, a Wise pattern mastopexy affords the versatility to move the nipple–areola complex greater distances and effectively manages large skin excess. The IMF is marked first with the lateral extension following the lateral breast curve rather than following the IMF to prevent a dog ear from occurring laterally. A circumferential wire areola marker (McKissock keyhole marker) is used to mark the new position of the nipple–areola complex. The device is centered 2 cm above the projection of the inframammary fold on the patient shown in Figure 34.1A–F (Fig. 34.1G, H). Curvilinear lines are then drawn from the bottom of the areola marking to the breast meridian at the IMF with the breast on tension superiorly (Fig. 34.1I). The degree of outward curvature is estimated based on the degree of breast laxity and can be confirmed on the operating room table after implant removal. The areola to new IMF distance is then marked and is typically 5–7 cm (Fig. 34.1J). Using the line from this marking to the IMF as the base of an isosceles triangle (a triangle with two equal sides and two equal angles), the remaining medial and lateral triangles are marked (Fig. 34.1K–M). The triangles marked may result in a shorter horizontal scar if wider vertical limbs are able to be drawn based on the laxity of the breast tissue.

Intraoperative technique

After completion of markings, the patient is brought to the operating room and placed supine on the operating room table. Preoperative antibiotics are given. General anesthesia is usually administered, although in cases of minor ptosis, local anesthesia with intravenous sedation will often suffice. Skin incisions are then made, depending upon the mastopexy pattern selected. The nipple–areola complex is stretched and incised to a diameter between 38 and 42 cm. De-epithelialization is then performed (Fig. 34.1N). For implant removal, an extracapsular dissection with capsulectomy is performed usually through the lower pole of the breast. The parenchymal incision is usually limited to 4–6 cm. If the implant is ruptured, a small opening is made in the capsule and the implant material removed prior to removing the remaining capsule. We favor complete capsulectomy, although in cases with a thick or densely adherent subpectoral capsule, dissection is occasionally limited to the anterior aspect of the capsule (Fig 34.1O).

Regardless of the mastopexy pattern selected, it is important to sit the patient up after capsulectomy and implant removal. The degree of skin removal is often much greater than the preoperative markings indicated, and it is often best to utilize a tailor-tacking approach in order to best shape the central breast mound. We favor conservative parenchymal undermining in order to recreate the central breast mound, and maintain our flaps at least 1 cm thick (Fig. 34.1P). Final closure is performed with absorbable inverted dermal sutures, followed by subcuticular closure and dermabond (Ethicon) or Steri-strips. Drains are usually placed. A second patient example is shown in Figure 34.2A–F.

Conclusion

It is always important to assess the patient’s needs as carefully as possible, so that both patient and physician are satisfied with the outcome of surgery (Fig. 34.2 shows a representative example). Implant removal will often exacerbate the degree of ptosis present, and both the patient’s skin quality, and amount and distribution of native breast tissue will determine postexplantation breast aesthetics. Proper recognition of the need for mastopexy following explantation helps to reduce the necessity of an anesthetic at a delayed date. For high risk patients such as smokers or those requiring the nipple–areola complex to be moved greater than 4 cm, we advocate mastopexy 2 to 3 months following explantation.

Chang BW. Mastopexy. In: Evans G, editor. Operative plastic surgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000:631-634.

Netscher DT. Aesthetic outcome of breast implant removal in 85 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113(3):1057-1059.

Netscher DT, Sharma S, Thornby J, Peltier M, Lyos A, Fate Mosharrafa A. Aesthetic outcome of breast implant removal in 85 consecutive patients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100(1):206-219.

Regnault P. Ptosis, asymmetry, tubular breast, and congenital anomalies. In: Owsley JQ, Peterson RA, editors. Symposium on aesthetic surgery of the breast. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1978.

Rohrich RJ, Parker TH. Aesthetic management of the breast after explantation: evaluation and mastopexy options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120(1):312-315.

Rohrich RJ, Beran S, Restifo RJ, Copit SE. Aesthetic management of the breast following explantation: evaluation of mastopexy options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(3):827-837.