Chapter 18 Mastopexy

Summary

Indication

Regardless of the etiology, a useful tool for the surgeon is to classify patients by the degree of ptosis present. The classification system used most frequently was first described by Regnault1 and grades the breast based on the position of the nipple relative to the inframammary fold (IMF) (Table 18.1).7 The amount of preoperative ptosis can be used as a guide to selecting the operation necessary to achieve correction.

| Grade I | Nipple at the level of the IMF, above the lower contour of the gland |

| Grade II | Nipple below the IMF, above the lower contour of the gland |

| Grade III | Nipple below the IMF and at the lower contour of the gland |

| Pseudoptosis | Normal nipple position with glandular tissue below the IMF |

IMF, inframammary fold.

Preoperative History and Considerations

For each patient, the surgeon should develop a strategy for reshaping and positioning the breast parenchyma and determine the need, if any, for additional soft tissue augmentation with an implant or autologous flap. Breast shaping can be elaborate or simple and may include combinations of suturing, local flaps, muscle slings, or placement of internal mesh support.2–5

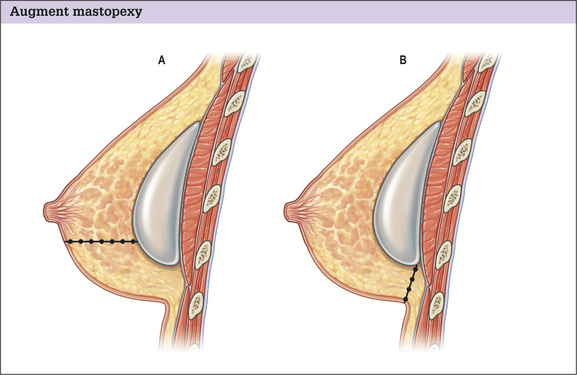

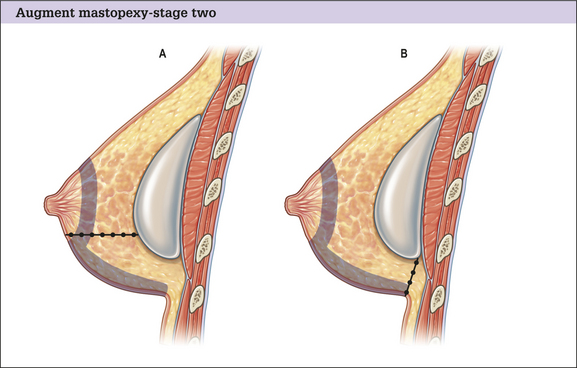

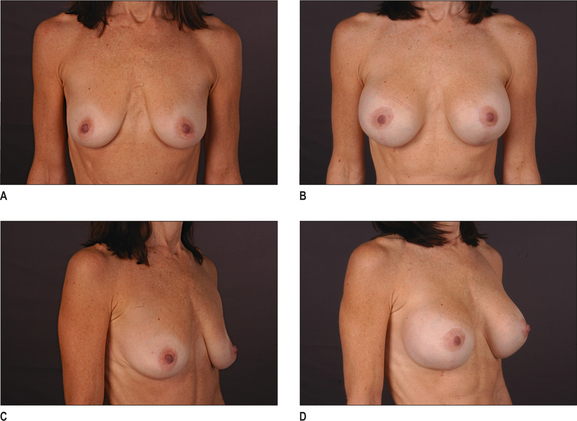

Combining augmentation with mastopexy can be accomplished safely for many patients. Clearly, adding an implant to an already complex operation will increase the number of variables that the surgeon must consider. Many women with ptotic breasts focus more on the loss of upper pole volume that has occurred as their breasts have aged, than on the change in nipple position that has accompanied it. An implant can be a very powerful tool in restoring youthful fullness to the upper pole.

Preoperative planning and dimensional analysis

Preoperative physical exam should include measurements as well as an assessment of tissue qualities and distribution. Significant asymmetries will be noted in most patients when carefully examined.6 It is important to recognize and point out any pre-existing asymmetries, spinal curvature, or chest wall deformities because these may be difficult to correct and can become noticeable in the postoperative period. Preoperative photographs with multiple views are obtained on all patients and maintained as part of the office record.

The soft tissue envelope should be characterized and the desired resultant breast form planned (Box 18.1). Once accomplished the surgeon can assimilate the information to select an appropriate implant, if desired, and plan the mastopexy approach. Use of the BioDIMENSIONAL® preoperative planning system (INAMED Corporation) can be used on patients requiring ptosis correction with augmentation.

Patient marking

Preoperative markings are made with the patient in an upright position and begin with:

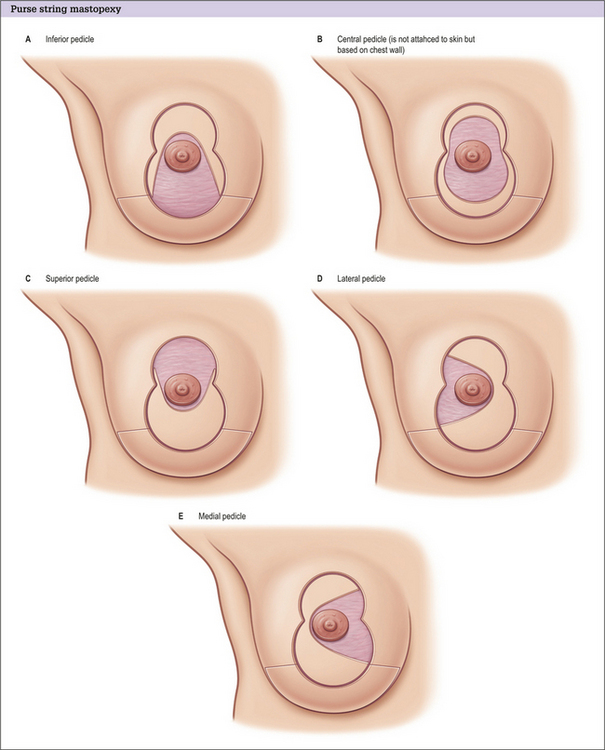

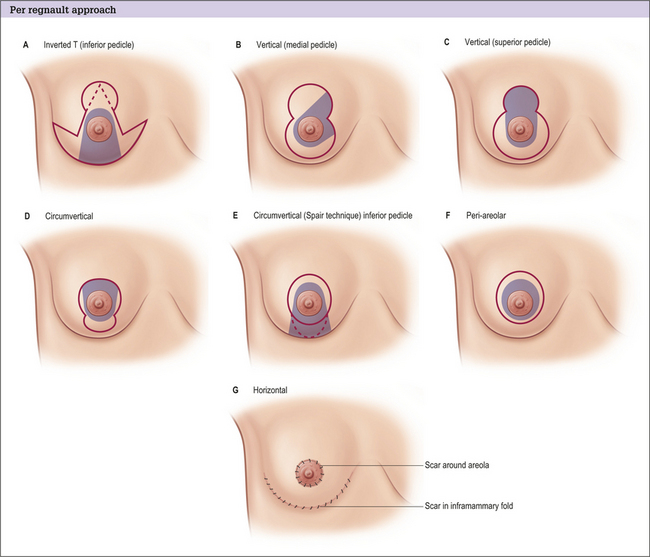

At this point, the surgeon should determine the planned excision pattern (Figs 18.1 and 18.2) and proceed with the appropriate marks. The degree of mastopexy will vary from a periareolar approach to a full inverted-T scar based on the amount of ptosis present. Variations in incision patterns are the same for augmentation mastopexy and mastopexy alone and are gradually increased to accommodate increasing amounts of breast tissue and ptosis.

Fig. 18.1 An individualized approach to skin tightening and excision is applied with increasing degrees of mammary ptosis.1 Thus lesser degrees of ptosis require no or little skin excision whereas increasing degrees require the most skin tightening or excision. A, Periareolar approach with internal rearrangement or insertion of implant. B, Periareolar excision. C, Circumareolar with vertical excision. D, Circumareolar plus ‘J’ excision, which with increasing ptosis, turns into a wider ‘J’ or ‘B’ excision. E, Circumareolar with vertical and small transverse excision. F, Wise pattern-type excision. With all these skin patterns an implant may be inserted, internal tissue rearrangement performed, or simply skin tightening.

Operative Approach

Implant selection and placement

Implant selection and placement are judged according to the preoperative measurements.

Decisions on implant size, shape, surface texture, and filling material are made based on the soft tissue components present. Selection of an implant with enhanced projection can offer the mechanical advantage of raising the position of the nipple-areola complex. In patients with minor amounts of ptosis, this approach can sometimes alleviate the need for a mastopexy. Likewise, it may in a sense ‘downstage’ a patient from one degree of ptosis to the next. Therefore, a patient who would need a circumvertical scar to achieve an adequate result may only need a periareolar tightening once the implant is in place. Our preference is to use form-stable highly cohesive gel anatomical implants with enhanced projection (F or X) for optimal results.

Once a device is selected, the surgeon must determine the implant’s location.

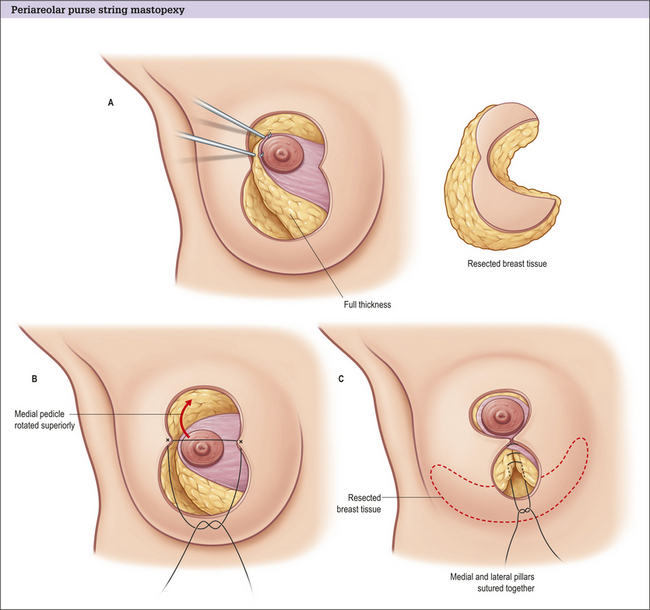

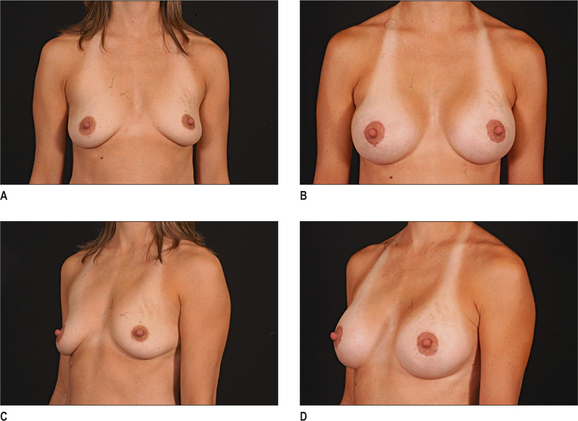

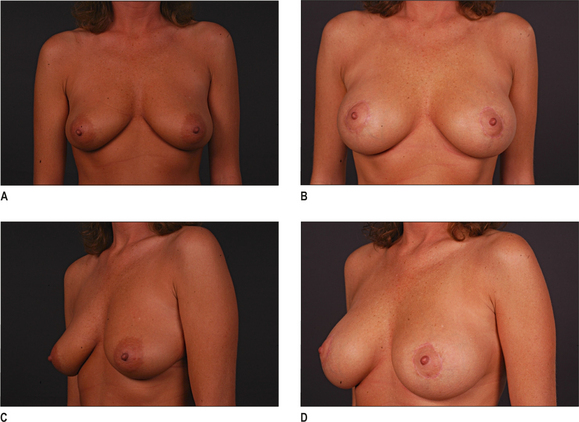

Closure is secured with a non-absorbable Gore-Tex® suture on a straight needle using a ‘pin-wheel’ or ‘wagon-wheel’ technique.11 When correctly placed, this suture controls the areolar diameter, helps to prevent areolar widening, and reduces periareolar wrinkling and pleats by evenly distributing tissues. A running subcuticular 5-0 Monocryl is then placed superficially, with care not to disrupt the previous suture (Fig. 18.5). (Post-operative results are in Figure 18.6.)

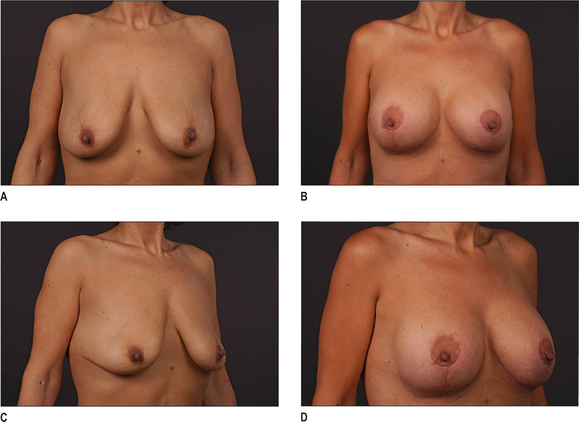

Moderate ptosis

Patients with moderate degrees of ptosis often require a vertical component to the scar with or without a short horizontal excision (Figs 20.7–20.9). The vertical component can be part of the preoperative design or added intraoperatively to distribute excess tissue encountered with the periareolar excision. In either situation, the inferior extent of the resection is kept at least 1-2 cm above the location of the IMF. As above, the preoperative markings are used as a guide and are confirmed and adjusted before making incisions.

Complications and Side Effects

Alterations in nipple sensation can be transient or permanent and are often a major source of concern for the patient. Careful attention is directed during implant placement to avoid overdissection or transection of the lateral intercostal cutaneous nerves.

1. Regnault B. Breast ptosis. Definition and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 1976;3(2):193-203.

2. Goes J.C., Landecker A., Lyra E.C., et al. The application of mesh support in periareolar breast surgery: clinical and mammographic evaluation. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2004;28(5):268-274.

3. Benelli L. A new periareolar mammaplasty: the ‘round block’ technique. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1990;14(2):93-100.

4. Benelli L.C. Mastopexy and reduction: The ‘round block’. In: Spear S.L., editor. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006:977-990.

5. Graf R., Biggs T.M. Mastopexy with a pectoralis muscle loop. In: Spear S.L., editor. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006:1008-1020.

6. Rohrich R.J., Hartley W., Brown S. Incidence of breast and chest wall asymmetry in breast augmentation: a retrospective analysis of 100 patients. Plast Reconstr Surg.. 2003;111(4):1513-1519.

7. Regnault P., Rolin D.K. Breast ptosis. In: Regnault P., editor. Aesthetic plastic surgery. Boston: Little, Brown and Co; 1984:539-558.

8. Whidden P.G. The tailor-tack mastopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;62(3):347-354.

9. Graf R.M., Bernardes A., Auersvald A., et al. Subfascial endoscopic transaxillary augmentation mammoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2000;24:216-220.

10. Graf R.M., Bernardes A., Rippel R., et al. Subfascial breast implant: a new procedure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111(2):904-908.

11. Hammond D.C. Augmentation mastopexy: general considerations. In: Spear S.L., editor. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006:1403-1416.

12. Rohrich R.J., Thornton J.F., Jakubietz R.G., et al. The limited scar mastopexy: current concepts and approaches to correct breast ptosis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(6):1622-1630.

13. Rohrich R.J., Beran S.J., Restifo R.J., et al. Aesthetic management of the breast following explantation: evaluation and mastopexy options. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;101(3):827-837.

14. Spear S.L., Kassan M., Little J.W. Guidelines in concentric mastopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1990;85(6):961-966.

15. Spear S.L., Giese S.Y., Ducic I. Concentric mastopexy revisited. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(5):1294-1299.

16. Hammond D.C. Reduction mammaplasty and mastopexy: general considerations. In: Spear S.L., editor. Surgery of the breast: principles and art. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006:971-976.

17. Hammond D.C. The SPAIR mammaplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 2002;29(3):411-421.