CHAPTER 23 Massive, Irreparable Rotator Cuff Tears

Rotator cuff disease is one of the most common reasons why patients seek medical attention. The prevalence of full-thickness tears increases substantially with age, and many of these tears go undetected because of a lack of symptoms. Tempelhof and colleagues1 have evaluated 411 asymptomatic adult shoulders ultrasonographically in patients older than 50 years. There were 96 (23.4%) full-thickness tears with an increased prevalence and tear size each decade (age, prevalence: 50-59, 13%; 60-69, 20%; 70-79, 31%; older than 80, 51%). In a similar study, Yamaguchi and associates2 performed bilateral ultrasound on 588 patients who presented with unilateral shoulder pain. There were 376 full-thickness tears discovered, 83 (22%) of which were asymptomatic. The authors reported an approximately 10-year difference between three subgroups of patients; the average age was 48.7 years for patients with no rotator cuff tear, 58.7 years for those with a unilateral tear, and 67.8 years for those with a bilateral tear. Patients who have asymptomatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears represent a population at risk because the natural history of these tears is that they progress and can result in eventual disability because of limited treatment options for those patients whose tears progress beyond a state of repair.

When a patient presents with a symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tear, it is difficult to argue against repair as the optimal treatment for those patients who are willing and able to undergo surgery and the required postoperative rehabilitation. However, there are patients whose tears are irreparable, thereby presenting a difficult challenge to the treating orthopedic surgeon. Rockwood and coworkers3 have reported an 83% patient satisfaction rate in 53 shoulders at an average of 6.3 years after open subacromial decompression and débridement of irreparable rotator cuff tears. The authors cited prior studies that demonstrated durable results in patients whose rotator cuff repairs failed, but who also underwent subacromial decompression. It was concluded that the improvements noted may, therefore, be caused by subacromial decompression and débridement of the torn cuff. Since the publication of their results, several studies4–7 have demonstrated lasting pain relief but variable functional gains from débridement and subacromial decompression, whether performed as an open repair or arthroscopically. Many of these studies compared cuff repair with decompression and débridement, and patients who underwent successful repair fared better in the long term. Certainly, rotator cuff repair should be attempted when possible, but irreparable lesions of the rotator cuff are a separate entity and the treatment, rehabilitation, and goals of therapy should be as well.

ANATOMY AND PATHOANATOMY

Irreparable Cuff

The rotator cuff consists of four muscles—subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor—whose tendons coalesce to envelop the humeral head at the anatomic neck. This design enables the rotator cuff to function as a unit to stabilize the humeral head in the center of the glenoid cavity throughout the full range of shoulder motion. Full-thickness rotator cuff tears have been classified according to cause, age of the tear, size, shape, number of tendons, and topography or trophicity.8 For the purpose of this chapter, focus will remain on tears that are massive and irreparable; these are tears that are chronic (longer than12 months), involve two or more tendons (more than 5cm in maximum dimension), are retracted to the glenoid margin, and/or demonstrate poor muscle trophicity on computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

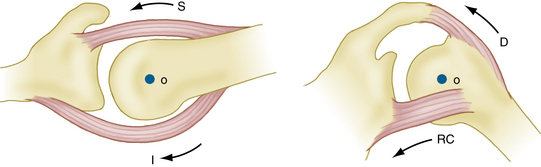

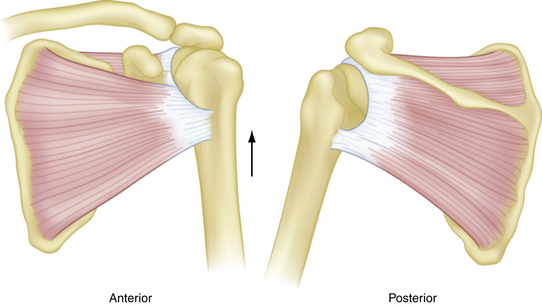

The symptoms most often associated with irreparable rotator cuff tears are pain and functional limitation. Pain can be the result of mechanical, biologic, and/or neurologic factors,9,10 any of which can mask a functional rotator cuff tear. Burkhart9 has described five essential biomechanical criteria that must be met for a tear to retain function (Table 23-1). Perhaps the most crucial of these is the integrity of the force couples about the glenohumeral joint. The remaining four criteria are a function of tear size, tear location, and degenerative condition of the tendon, all of which are important but may be considered in direct relation to the integrity (or lack thereof) of the glenohumeral force couples. Force couples exist in the coronal and transverse planes, and represent the contribution of the rotator cuff to dynamic glenohumeral joint stability during active flexion and abduction (Fig. 23-1). For review, a force couple is defined as two equal but oppositely directed forces that act simultaneously on opposite sides of an axis of rotation. Translational forces are cancelled out, linear motion is eliminated, and torque is produced. Inman and colleagues11 have described the coronal plane force couple, which provides superior-inferior stability by depressing the humeral head as resistance against the upward force of the deltoid during active abduction. Loss of the coronal plane force couple results in superior head migration, but not necessarily loss of daily function. The transverse force couple12 is composed of the subscapularis anteriorly and the infraspinatus–teres minor posteriorly, and provides anteroposterior glenohumeral stability throughout active abduction. Disruption of the anterior or posterior contribution of the transverse force couple results in loss of concavity compression, a pathologic increase in translation or subluxation of the humeral head toward the cuff deficiency, and decreased active abduction.13 As such, these patients will often complain of pain and loss of function.

TABLE 23-1 Biomechanical Criteria of Functional Rotator Cuff Tear

| Grade | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Force couples must be intact in the coronal and transverse planes. |

| 2 | A stable-fulcrum kinematic pattern must exist. |

| 3 | The shoulder’s suspension bridge must be intact. |

| 4 | The tear must occur through a minimal surface area. |

| 5 | The tear must possess edge stability. |

From Burkhart SS. Reconciling the paradox of rotator cuff repair versus débridement: a unified biomechanical rationale for the treatment of rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1994;10:4-19.

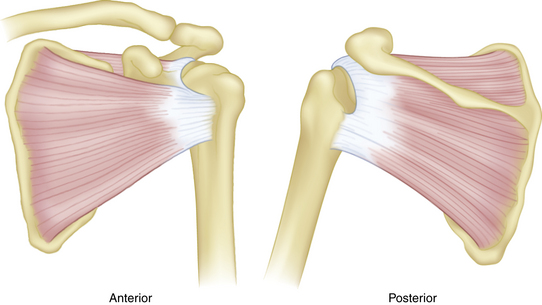

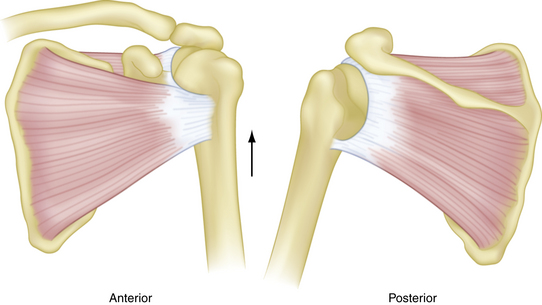

The importance of tear size and location on the transverse force couple, and the subsequent effects on function were further demonstrated by Burkhart in a fluoroscopic evaluation of 14 patients with massive rotator cuff tears.14 His observations have led to the description of three kinematic patterns (Figs. 23-2 to 23-4): type I, stable fulcrum; type II, unstable fulcrum; and type III, captured fulcrum. In essence, functional tears retain a critical portion of the anterior (subscapularis) and posterior (infraspinatus–teres minor) limbs of the transverse force couple, and the tear does not extend below the equator of the humeral head.

FIGURE 23-4 Captured fulcrum kinematics. A complete tear of the supraspinatus with extension anteriorly and posteriorly disrupts the coronal plane force couple to allow proximal humeral head migration. Patients may still be able to elevate the extremity if deltoid strength is sufficient.

(From Burkhart SS. Fluoroscopic comparison of kinematic patterns in massive rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;(284):144-152.)

The integrity of the transverse force couple does not always correlate with patient function. Kelly and associates15 have performed electromyography on normal controls, and compared their muscle firing patterns with those of patients who had symptomatic and asymptomatic combined tears of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons. None of the subjects had glenohumeral or acromioclavicular degenerative changes. Symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears demonstrated increased muscle firing patterns compared with controls. Asymptomatic patients had increased firing in the intact subscapularis, whereas symptomatic patients demonstrated increased firing of the torn supraspinatus and infraspinatus musculature, with compensatory periscapular muscle recruitment and overall symptomatic shoulder dysfunction. It was unclear why patients who had similar tear patterns demonstrated different muscle firing patterns.

Biceps Tendon

The long head of the biceps tendon, described as the fifth tendon of the rotator cuff,16 is thought to contribute to shoulder flexion and abduction and provide glenohumeral joint stability during rotation. Warner and McMahon17 have provided radiographic evidence of the superior stabilizing effect of the biceps tendon. On the other hand, Yamaguchi and coworkers18 have performed an electromyographic evaluation of biceps activity during 10 basic shoulder motions and reported very little biceps activity. Although its functional contributions may be debatable, lesions of the biceps tendon often coexist with massive rotator cuff tears and can be a significant source of pain. Walch and colleagues19 and Boileau and associates 20 have reported reliable pain relief and improved function after arthroscopic biceps tenodesis or tenotomy in patients who had irreparable massive rotator cuff tears with an intact teres minor, no pseudoparalysis, and no severe rotator cuff arthropathy.

Other Pathologic Entities

There are other pain generators that can cause functional limitations and should be evaluated clinically to determine whether they play a role in the patient’s symptoms. The acromioclavicular (AC) joint begins to degenerate during early adulthood, and is a common source of pain in patients who have rotator cuff disease. Arthroscopic resection of the distal clavicle, without destabilizing the AC joint, is a reliable method to relieve pain sufficiently to restore a degree of function.21 Subacromial bursitis is associated with increased expression of substance P in the primary afferent nerves of the bursal tissue, and is associated with chronic pain. Glenohumeral arthritis can stimulate local or proliferative synovitis, which is another potential source of pain.

CLINICAL EVALUATION

History

Patient age has important implications about the quality of the cuff tissue and the size of the tear. Older patients often present with painful, chronic, atrophic large or massive rotator cuff tears and a progressive loss of shoulder function. Cuff tissue in these patients may be less amenable to repair. Younger patients will more often describe an acute event that precipitated symptoms of pain and functional loss, and their tissues will most likely be healthier and more likely to heal. These probabilities are based on two broad categories of patients and it is important not to focus solely on age. Hattrup22 is often referenced for qualifying 65 years of age as the point at which results of rotator cuff repair decline. He reported 77% excellent results in patients older than 65 years and 89% excellent results in patients younger than 65 years after open repair of rotator cuff tears of all sizes. In this study, as patients aged, tear size increased and results declined. However, pain relief and patient satisfaction were high in both groups. Hence, these results do not make a solid argument against repair based solely on patient age.

The duration of symptoms also provides a clue to the quality of the cuff tissue, amount of retraction, and overall reparability of the tendons. Lam and Mok23 have reported 44% good or excellent and 23% poor results after open repair of massive (more than 5 cm) rotator cuff tears in 69 patients who were 65 years or older (mean, 75 years). Preoperative symptoms for longer than 34 months predicted poor outcome, with 100% sensitivity, 98% specificity, and 94% positive predictive value. Female gender and medical comorbidities (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] grade higher than III) were also associated with poor outcomes. Women accounted for 23 of 24 patients whose cuff tissue was graded as poor intraoperatively, with subsequent inability to adequately repair the torn tendon to bone in 16 of these patients. There was no discussion of ASA severity in relation to patient gender, and age was not independently related to poor outcomes.

Corticosteroid injections are used by many surgeons as a component of nonoperative treatment in subacromial impingement. However, the risks of this treatment may eventually outweigh any potential benefits. Watson24 has demonstrated that increasing numbers of injections lead to softening of the cuff tissue, larger tears, and poorer results. In this study, however, it was the older patients who had received more injections, had larger tears, and demonstrated worse cuff tissue. These factors may represent the natural history of the disease as much as the impact from the number of injections received. The study concluded by recommending that a decision regarding repair should be made early, before patients received the critical number of four injections.

It is crucial to know whether patients have had previous surgery (or surgeries) on the affected shoulder. The results of revision rotator cuff repair decline when there is deltoid detachment, an aggressive prior acromionectomy, poor quality cuff tissue, enlargement of the tear, and/or retraction. Obtaining a copy of the operative report can provide abundant information to help plan the next step in treatment. Deep infection after rotator cuff repair occurs in up to 1.9% of patients,25 with Propionibacterium acnes as the most common pathogen. Infection with P. acnes can be an indolent, subclinical source of pain, and must be ruled out as a cause of failure. Other important factors to address in the history are the patient’s functional status, goals of treatment, and hand dominance. An older sedentary patient whose primary complaint is pain in their nondominant arm may not wish to undergo rotator cuff repair or other reconstructive procedure, even if he or she is a candidate for a more aggressive approach.

Physical Examination

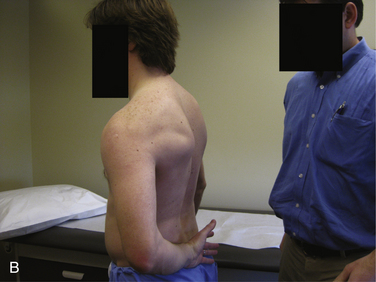

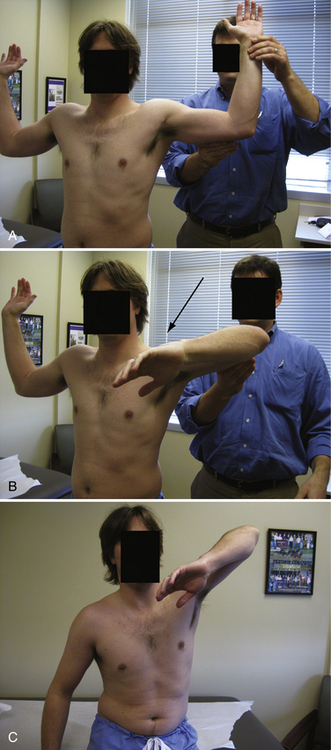

The drop arm sign (Fig. 23-5) is positive when the patient cannot maintain the arm at 90 degrees of abduction, which indicates supraspinatus insufficiency. The belly press test (upper subscapularis) is positive when the patient is unable to maintain the elbow anterior to the midsagittal plane of the body with the palm pressing on the abdomen (Fig. 23-6). The lift-off test (lower subscapularis) is positive when the patient cannot hold the hand off the lower lumbar region with the shoulder in full internal rotation and the elbow maintained in approximately 60 degrees of flexion (Fig. 23-7). Massive irreparable tears demonstrate typical findings, known as lag signs, that are characteristic of the specific pathology. The external rotation lag sign (infraspinatus) is positive when the patient cannot maintain a position of full external rotation in adduction when the hand is placed in that position by the examiner (Fig. 23-8). The hornblower sign (teres minor) is positive when the patient cannot maintain full external rotation in 90 degrees of abduction when the hand is placed in that position by the examiner (Fig. 23-9). Because pain can severely limit shoulder strength, strength testing should be performed before and after diagnostic anesthetic injection to evaluate for differences.

FIGURE 23-8 A, B, The external rotation lag sign tests the infraspinatus. It is positive when the patient cannot maintain a position of full external rotation in adduction when the hand is placed in that position by the examiner (arrow).

Cuff tear arthropathy is the end stage of rotator cuff disease and patients’ treatment options typically are limited to open reconstructive procedures. In patients who, for various reasons, are not candidates for these more invasive procedures, a diagnostic suprascapular nerve block may be placed 2 cm medial to the posterior border of the acromioclavicular joint and may provide a reasonable prediction of pain relief if the patient and surgeon are exploring palliative options such as suprascapular nerve decompression. In our practice, diagnostic injections are routinely performed, and the small investment of time is rewarded by a substantial amount of information that helps formulate a successful treatment plan.

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Plain Radiographs

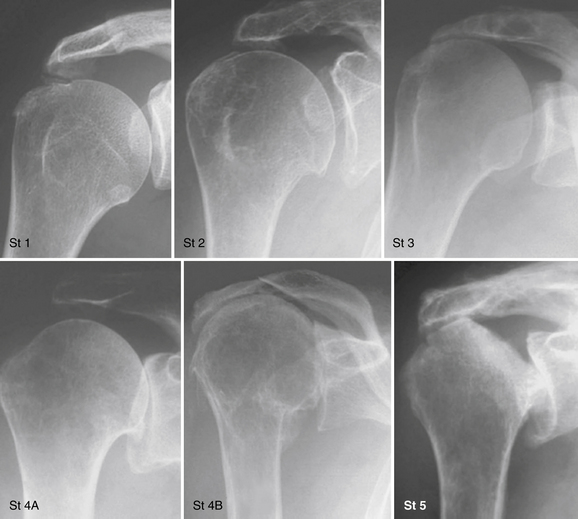

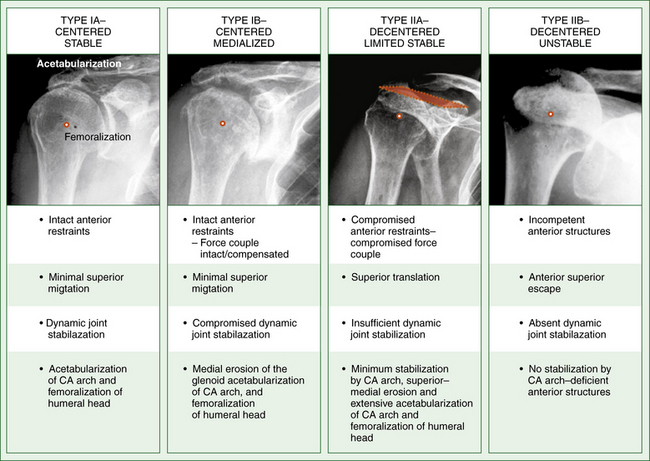

Plain radiographs are a routine element in the initial examination of patients who present with shoulder pain. The standard views are always obtained perpendicular to the plane of the scapula; these include anteroposterior views in internal and external rotation, a scapular Y view (10 to 15 degrees of caudal tilt in the lateral scapular plane), and an axillary lateral view. Osseous changes that are observed in patients with massive rotator cuff tears include acromiohumeral narrowing secondary to proximal humeral head migration, greater tuberosity sclerosis and excrescences, subacromial spurs, and acromioclavicular joint arthritis. Accurately measuring the acromiohumeral distance without fluoroscopic control is difficult because of projection and magnification differences, but can suggest a massive cuff tear when it is less than 6 mm.19,26 In patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears, the Hamada staging system27 is useful for grading degenerative changes of the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 23-10). Hamada stages 4 and 5 are associated with radiographic glenohumeral degenerative changes, which presents a relative contraindication to arthroscopic débridement of massive cuff tears. The Seebauer classification28 system is useful for evaluating glenohumeral joint stability in the presence of massive rotator cuff tears (Fig. 23-11). Glenoid bone loss caused by erosive changes is graded according to the Favard classification (Fig. 23-12).

Computed Tomography

Computed tomography is useful for the evaluation of rotator cuff tears and is ideal for grading the severity of bone loss in severe cuff tear arthropathy. The Goutallier grading system (Table 23-2) of rotator cuff muscle atrophy and fatty infiltration is based on CT imaging, and remains an important method for determining whether a tear has potential to heal.29 A higher degree of preoperative fatty infiltration on CT (grade 3 or higher) was associated with recurrent tears and lower Constant scores.

| Grade | Features |

|---|---|

| 0 | No fatty deposits |

| 1 | Some fatty streaks |

| 2 | More muscle than fat |

| 3 | As much muscle as fat |

| 4 | Less muscle than fat |

From Goutallier D, Postel JM, Gleyze P, et al. Influence of cuff muscle fatty degeneration on anatomic and functional outcomes after simple suture of full-thickness tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:550-554.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is an excellent method for evaluating rotator cuff tears, the number of tendons involved, the degree of fatty infiltration and muscle atrophy, and the potential for healing after repair. The degree of fatty infiltration on MRI is graded in the same manner as on CT, and is best visualized on sagittal T1-weighted image sequences. Grade 3 or 4 fatty infiltration associated with chronic cuff tears is irreversible and is indicative of poor tendon quality.30 In an older patient with low functional demands, this represents a tear with poor healing potential. Evaluation of bone defects with MRI is not as reliable as CT, and both techniques should be considered when appropriate for deciding on ultimate treatment. There is likely no added benefit of MR arthrography over standard MRI in patients who have massive tears.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is useful for detecting rotator cuff tears, is less expensive than MRI or CT arthrography, and is noninvasive. It has been shown to be a moderately accurate method for assessing atrophy and fatty infiltration of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles.31 However, this imaging modality requires an experienced technician and, although the accuracy rate has been reported to be high (96%),32 it is highly dependent on the skill of the ultrasonographer.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Conservative Management

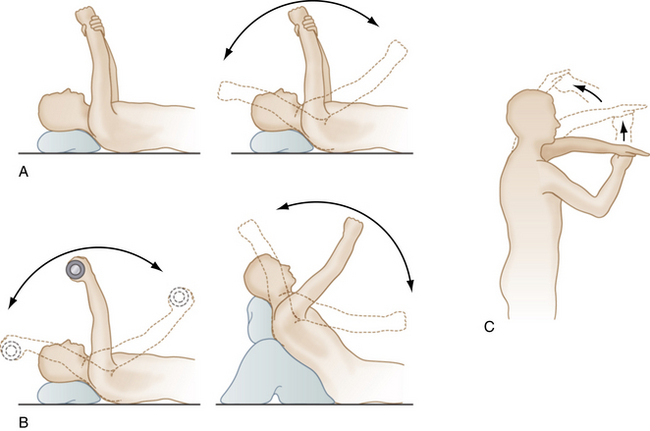

Conservative therapy is the traditional first line of treatment in many conditions about the shoulder. It involves activity modification, physical therapy, and pain management with consideration of periodic corticosteroid injections and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Aggravating activites should be avoided, and consideration should be given to more aggressive management (even surgical) in younger patients to maximize potential functional return. Physical therapy includes rehabilitation of the cuff-deficient shoulder, with limited goals in mind (Fig. 23-13). These limited goals focus on pain relief, personal hygiene, and the ability to feed oneself with a utensil. Levy and coworkers33 have recently demonstrated the effectiveness of anterior deltoid retraining in 17 older patients (mean age, older than 80 years) with irreparable, massive, three-tendon rotator cuff tears and pseudoparalysis. Degenerative changes were classified according to the Hamada staging system and there were 5 patients who demonstrated stage 2 degenerative changes, 7 with stage 3 changes, and 5 with stage 4 degeneration. The average Constant score improved from 26 to 60 points at a minimum follow-up of 9 months. Prior to initiation of deltoid retraining exercises, no patient could elevate the affected arm above 60 degrees. At the time of follow-up, average forward elevation was 160 degrees (range, 150 to 180 degrees). Pain relief (no pain medication) and ability to perform daily activities was achieved in 14 of 17 patients. One patient went on to reverse shoulder arthroplasty with a good functional result, and another achieved pain relief after arthroscopic subacromial decompression. The authors indicated that the 14 patients who improved with rehabilitation were converted from an unstable fulcrum to captured fulcrum kinematics, as described earlier.14 Anterior deltoid retraining can help some older patients avoid surgery, and those patients who fail conservative therapy will nevertheless gain the added benefit of preoperative deltoid strengthening to assist with postoperative rehabilitation.

Arthroscopic Treatment

Older patients who fail conservative therapy face the decision of whether to proceed with surgical management. Arthroscopic treatment of massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears includes débridement, decompression of the subacromial space, biceps, and/or partial distal clavicle resection, suprascapular nerve release and, in certain situations, partial rotator cuff repair. Rockwood and colleagues,3 Gartsman,7 and Ellman and associates5 have demonstrated good pain relief, improved function, and higher patient satisfaction rates following arthroscopic débridement and subacromial decompression in patients with large or massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Kempf and coworkers34 have recommended against this treatment in patients younger than 50 to 60 years of age because of less satisfying subjective and functional results. Recently, Liem and colleagues35 have reported improved Constant scores from 24 preoperatively to 69 postoperatively in 31 patients (average age 70.6 years) following arthroscopic débridement and subacromial decompression at a mean of 47 months of follow-up. Biceps tenotomy was performed in 77% and acromioplasty was not performed in any patient to prevent loss of the coracoacromial arch.

Boileau and associates20 and Walch and coworkers19 have reported good pain relief following biceps tenotomy or tenodesis in patients without severe cuff arthropathy or pseudoparalysis. Klinger and colleagues36 found no difference between arthroscopic decompression and decompression with biceps tenotomy in 32 patients at an average 31 months of follow-up. Similar increases in Constant scores were observed for both groups, and outcomes supported the use of tenotomy for older patients with massive irreparable tears. Klinger and associates, in a separate study,37 listed preoperative glenohumeral arthritis, poor passive range of motion, a high-riding humeral head, and a subscapularis tear as potential predictors of poor outcome from this technique.

Occasionally, a patient may present with an acute, symptomatic extension of a massive, previously asymptomatic irreparable tear with an associated abrupt loss of function. In the absence of significant glenohumeral degenerative changes (Hamada stages 1 to 4A), arthroscopic partial rotator cuff repair may be a feasible option to restore the recently disrupted force couple and potentially return the patient to the previous level of function. For posterosuperior tears, this includes reattaching and advancing at least the lower portion of the infraspinatus tendon. Anterosuperior tears require reattachment of as much of the subscapularis tendon as possible. Patients for whom these techniques are unlikely to be successful are those who demonstrate Hamada stage 4B or 5 degenerative changes, stage 3 or 4 fatty infiltration of the teres minor and/or subscapularis, and/or anterosuperior escape.

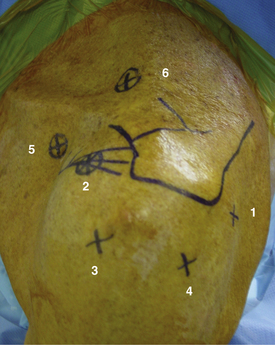

Patient Positioning and Portal Placement

Patients are placed in a modified, upright beach chair position (the dinner chair position; Fig. 23-14). All patients are placed on a bean bag that helps maintain body position throughout the procedure. Two or three pillows are placed beneath the knees and feet to minimize hamstring and lumbar stress. All bony prominences are well padded to prevent pressure points. Articulated head and arm holders are used to provide complete shoulder exposure and stable, yet versatile, arm positioning during the operation. Anatomic landmarks are drawn on the skin for portal placement identification (Fig. 23-15), with the arm in neutral rotation. Three portals are used for standard arthroscopic débridement, decompression, and distal clavicle excision. A fourth portal is used for rotator cuff repair. If biceps tenodesis will be performed, another portal is used directly, anterior to the intertrabecular groove. Arthroscopic suprascapular nerve decompression requires two additional portals, one placed 1 cm medial to the coracoid process tip and another placed 2 cm medial to the posterior margin of the acromioclavicular joint.

Diagnostic Arthroscopy, Débridement, and Decompression

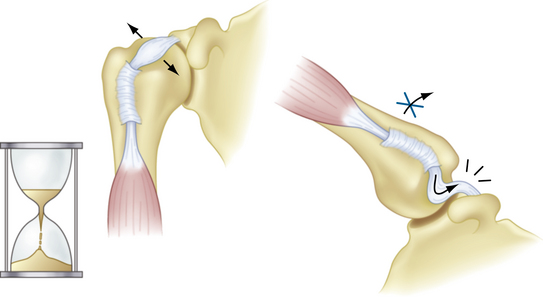

The patient’s affected arm is secured in the sterile portion of the articulated arm holder in neutral rotation and the arthroscope is inserted through a posterior viewing portal. A spinal needle is used to confirm placement of the anterior portal through the rotator interval, and a disposable cannula is inserted into the joint. Diagnostic arthroscopy begins with evaluation of the superior labrum and biceps tendon. Biceps pathology may present as partial or complete detachment, fraying, instability (subluxation or dislocation), or an hourglass appearance (Fig. 23-16). In this population of patients, biceps tenotomy is typically performed. Occasionally, in active male patients with the dominant side affected, biceps tenodesis may be considered. If the rotator interval capsular tissue is thickened and restricts glenohumeral motion in external rotation, an electrothermal ablation device is used to release this tissue. The articular surfaces are evaluated, and the size and retraction of the rotator cuff tear are determined. A shaver is inserted through the anterior portal and débridement of inflamed synovium and degenerative labral tissue is performed. When biceps tenodesis is planned, a spinal needle is inserted percutaneously to transfix the tendon at its entry into the intertrabecular groove prior to biceps release from the supraglenoid tubercle. When the intra-articular work is complete, the arthroscope is moved into the subacromial space. A spinal needle is placed percutaneously through the marked site for the anterolateral portal in the same transverse plane as the camera. A skin incision is made and a blunt trocar is inserted into the subacromial space. An electrothermal ablation device is inserted atraumatically through the anterolateral portal, and the undersurface of the anterior acromion is cleared of bursal tissue. The anterior edge, anterolateral corner, and lateral margin of the anterior third of the acromion are carefully exposed by removing bursal tissue from the undersurface of the acromion. As bursal tissue is resected, the obliquely oriented fibers of the coracoacromial ligament will come into view, marking the anterior margin of the débridement. The anterior-most fibers of the coracoacromial ligament, which attach to the anterior acromion, are preserved intact. Along the lateral margin of the acromion, the coracoacromial ligament is intimately attached to the deep deltoid fascia and the rounded edge of the acromion marks the extent of débridement, with care taken to not detach the coracoacromial ligament. It is critically important to exercise caution during this step to ensure that the integrity of the deltoid origin and coracoacromial arch are not disrupted. A burr is inserted through the anterolateral working portal and a limited acromial smoothing is performed to remove subacromial excrescences from the anterolateral and lateral margins of the acromion. The arthroscope is then placed in the anterolateral portal. The electrothermal ablation device is inserted through the posterior portal. The anterior acromial edge is cleared of any residual bursal tissue. The burr is then inserted posteriorly to smooth the inferior portion of the anterior third of the acromion gently, without destabilizing the coracoacromial arch. Once the inferior acromion is smooth and flat from medial to lateral, further decompression, if required, can be achieved on the humeral side by removal of bony prominences on the greater tuberosity (tuberoplasty). Subacromial bursectomy is then performed to remove thickened, hypertrophic bursal tissue that surrounds the irreparable cuff.

Biceps Tenodesis

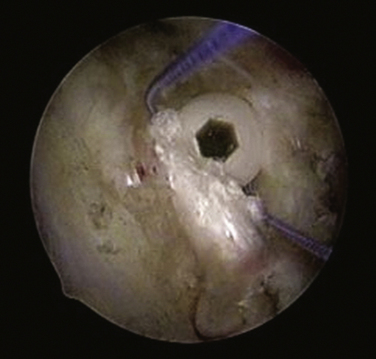

If biceps tenodesis is planned, the viewing cannula remains in the anterolateral portal and the spinal needle that stabilizes the biceps tendon is identified in the subacromial space. The arm is brought into approximately 30 degrees of flexion, which is the key to working arthroscopically in the anterior subdeltoid space. The electrothermal ablation device is used to clear any remaining bursal tissue in the region of interest surrounding the spinal needle. The previously marked portal is created directly anterior to the transverse humeral ligament, and will serve as the working portal for biceps tenodesis. A blunt trocar is inserted to dissect bursal tissue bluntly away from the pectoralis reflection (the falciform ligament) and proximally over the intertrabecular groove. The electrothermal ablation device is used to open the transverse humeral ligament over the bicipital groove down to the level of the pectoralis reflection, and great care is taken to avoid injury to the biceps tendon. An arthroscopic probe is used to deliver the biceps tendon into the subacromial space (Fig. 23-17). The spinal needle is removed once the probe has engaged the biceps tendon. A grasper is then used to exteriorize the biceps tendon through the biceps working portal. The elbow is flexed to relax the biceps and permit maximal tendon delivery through the wound (approximately 4 to 5 cm). One cm of tendon is removed sharply, and the biceps is doubled on itself over a length of 15 to20 mm with a locking suture (Fig. 23-18). The camera is reinserted into the anterolateral viewing portal, and the site for the tenodesis is located 1cm from the top of the groove. A guide pin is inserted and a 7-mm cannulated reamer is used to prepare a 30-mm-deep bony socket. A 4-mm burr is used to chamfer the inferior and lateral margins of the socket to ensure tendon to bone healing and prevent traumatic rupture of the tendon after fixation. The biceps is delivered into the socket with an arthroscopic grasper, a Nitinol guide pin is placed superior to the biceps tendon, and a 7-mm bioabsorbable interference screw is inserted to complete the biceps tenodesis (Fig. 23-19). As the screw engages the cortex, the elbow is extended to prevent overtensioning the biceps. If bone is severely osteopenic, soft tissue suture tenodesis or simple tenotomy may be the better option.

Rotator Cuff Repair

Once the posterolateral viewing portal has been established, the cuff is mobilized on its bursal and articular sides to the greatest extent possible. With the arm adducted, the torn cuff is evaluated to determine how much of the tear can be reapproximated to the tuberosity without undue tension, paying particular attention to the posterior (teres minor, lower infraspinatus) and anterior (subscapularis) limbs of the transverse force couple. On the bursal side, the adhesions are released between the scapular spine and retracted cuff tendon. In chronic, retracted massive cuff tears, the tendon may be scarred to the undersurface of the acromion; the tendon can be elevated away from the bone with an arthroscopic liberator or similar device to allow for greater cuff mobilization. On the articular side, the cuff is mobilized off the glenoid, taking care not to extend more than 2 cm medially to the glenoid rim to prevent injury to the suprascapular nerve. Anteriorly, if the subscapularis is torn, it is mobilized anterior and posterior to the tendon by releasing adhesions to the coracoid and within the subcoracoid bursa. Following mobilization, the bed for tendon repair is established. A recently developed all-arthroscopic bone-tunneling device enables cuff repair without the use of suture anchors. Each bone tunnel is triple-loaded with high-tensile strength suture (Fig. 23-20), and sutures are placed to provide a footprint compression repair. The medial bridge sutures act in a similar manner as a modified Mason-Allen stitch to prevent lateral sutures from pulling through the tendon (Fig. 23-21).

Acromioclavicular Joint and the Suprascapular Nerve

When débridement, decompression, biceps tenodesis, and/or cuff repair are complete, distal clavicle resection is performed if the joint is symptomatic and there is no acromial stress fracture or unstable os acromiale present. The anterolateral portal is used for viewing and a blunt trocar is inserted through the anterior portal to sweep tissue away from the undersurface of the AC joint. The inferior capsule of the acromioclavicular joint is opened, and a limited distal clavicle excision is performed (7 mm for men, 5 mm for women). A hooded 4-mm burr is used to set the plane of resection, and an unhooded burr is used to complete the resection. It is critically important that the posterior and superior capsules not be released or débrided to prevent symptomatic horizontal plane AC joint instability. A motorized shaver is used to remove any remnants of intra-articular disk material.

If a suprascapular nerve block was done preoperatively in the clinic setting with a good degree of pain relief, then the surgeon may proceed with suprascapular nerve decompression. Recent work has demonstrated electromyographic suprascapular nerve changes in more than 30% of patients with massive rotator cuff tears.10 The accompanying video, narrated by the senior author (SGK), provides a step by step description of the approach, dissection, identification, and decompression of the suprascapular nerve. The coracoid process is the key to this portion of the procedure because it keeps the surgeon oriented and serves as a guide for dissection to the suprascapular nerve and artery.

PEARLS& PITFALLS

POSTOPERATIVE REHABILITATION PROTOCOL

Débridement without Repair (Including Biceps Tenodesis)

Following débridement without cuff repair, no sling is used and early gentle passive range-of-motion exercises and scapular isometrics are begun immediately. Once patients have restored relatively pain-free active and passive motion in all planes (approximately 3 weeks), a strengthening program is initiated. If a biceps tenodesis is performed, strengthening is not performed during the first 6 postoperative weeks. It is imperative to strengthen and retrain both the anterior deltoid and scapular stabilizers to provide the maximum possible active elevation in patients with a cuff deficient shoulder. The Reading Shoulder Institute deltoid regimen is an excellent program for these patients, and begins with active supine strengthening exercises.33 As patients develop strength and confidence, body position gradually increases from a supine to seated position during strengthening exercises. It is anticipated that some degree of analgesia (NSAIDs, low-dose narcotics) will be required in the earlier phases of rehabilitation, and that this requirement will decrease or cease by 6 to 12 weeks postoperatively.

Débridement with Partial Rotator Cuff Repair

Patients are placed in a sling with a small abduction pillow for 6 weeks postoperatively. Weeks 0 to 3 allow passive forward flexion to 90 degrees and full passive external rotation. Scapular isometrics are begun while in the sling to reestablish shoulder girdle proprioception. During weeks 4 to 6 full passive forward flexion is allowed, along with full passive external rotation. If the subscapularis was also repaired, passive external rotation is limited to 30 degrees for the entire 6 weeks. Weeks 7 to 9 introduce active range-of-motion exercises and internal rotation is permitted. Pulley and pendulum exercises also begin at this time. Aquatic therapy (if possible) is also begun at week 7. Strengthening begins at week 10, and includes the deltoid strengthening regimen described earlier.

1. Tempelhof S, Rupp S, Seil R. Age-related prevalence of rotator cuff tears in symptomatic shoulders. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1999;8:296-299.

2. Yamaguchi K, Ditsios K, Middleton WD, et al The demographic and morphological features of rotator cuff disease: a comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 88; 2006:1699-1704.

3. Rockwood CA, Williams GR, Burkhead WZ. Débridement of degenerative, irreparable lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:857-866.

4. Esch JC, Ozerkis LR, Helgager JA, et al Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: results according to the degree of rotator cuff tear. Arthroscopy, 4; 1988:241-249.

5. Ellman H, Kay S, Wirth M Arthroscopic treatment of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: 2-7 year follow-up study. Arthroscopy, 9; 1993:195-200.

6. Levy HJ, Gardner RD, Lemak LJ. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression in the treatment of full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1991;7:8-13.

7. Gartsman GM. Massive, irreparable tears of the rotator cuff. Results of operative débridement and subacromial decompression. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:715-721.

8. Ciepiela MD, Burkhead WZJr. Classification of rotator cuff tears. In: Burkhead WZJr, editor. Rotator Cuff Disorders. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:100-107.

9. Burkhart SS Reconciling the paradox of rotator cuff repair versus débridement: a unified biomechanical rationale for the treatment of rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy, 10; 1994:4-19.

10. Costouros JG, Porramatikul M, Lie DT, Warner JJ. Reversal of suprascapular neuropathy following arthroscopic repair of massive supraspinatus and infraspinatus rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1152-1161.

11. Inman VT, Saunder CM, Abbott LC. Observations on the function of the shoulder joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1944;26:1-30.

12. Saha AK. Dynamic stability of the glenohumeral joint. Acta Orthop Scand. 1971;42:491-505.

13. Parsons IMIV, Apreleva M, Fu F, Woo S. The effect of rotator cuff tears on reaction forces at the glenohumeral joint. J Orthop Res. 2000;20:439-446.

14. Burkhart SS Fluoroscopic comparison of kinematic patterns in massive rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res (284); 1992:144-152.

15. Kelly BT, Williams RJ, Cordasco FA, et al. Differential patterns of muscle activation in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:165-171.

16. Habermeyer P, Walch G. The biceps tendon and rotator cuff disease. In: Burkhead WZJr, editor. Rotator Cuff Disorders. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1996:142-159.

17. Warner JJ, McMahon PJ. The role of the long head of the biceps brachii in superior stability of the glenohumeral joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:366-372.

18. Yamaguchi K, Riew KD, Galatz LM, et al Biceps activity during shoulder motion: an electromyographic analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 336; 1997:122-129.

19. Walch G, Edwards TB, Boulahia A, et al Arthroscopic tenotomy of the long head of the biceps in the treatment of rotator cuff tears: clinical and radiographic results of 307 cases. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 14; 2005:238-246.

20. Boileau P, Baqué F, Valerio L, et al. Isolated arthroscopic biceps tenotomy or tenodesis improves symptoms in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:747-757.

21. Mullet H, Benson R, Levy O. Arthroscopic treatment of a massive acromioclavicular joint cyst. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:446.

22. Hattrup SJ Rotator cuff repair: relevance of patient age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 4; 1995:95-100.

23. Lam F, Mok D Open repair of massive rotator cuff tears in patients 65 years of age or over: is it worthwhile. J Shoulder Elbow Surg, 13; 2004:517-521.

24. Watson M. Major ruptures of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1985;67:618-624.

25. Athwal GS, Sperling JW, Rispoli DM, Cofield RH. Deep infection after rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2007;16:306-311.

26. Green A Chronic massive rotator cuff tears: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg, 11; 2003:321-331.

27. Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res (254); 1990:92-96.

28. Visotsky JL, Basmania C, Seebauer L, et al Cuff tear arthropathy: pathogenesis, classification, and algorithm for treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 86; 2004:35-40.

29. Goutallier D, Postel JM, Gleyze P, et al. Influence of cuff muscle fatty degeneration on anatomic and functional outcomes after simple suture of full-thickness tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:550-554.

30. Gerber C, Fuchs B, Hodler J. The results of repair of massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:505-515.

31. Strobel K, Hodler J, Meyer DC, et al Fatty atrophy of supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles: accuracy of US. Radiology, 237; 2005:584-589.

32. Teefey SA, Hasan SA, Middleon WD, et al Ultrasonography of the rotator cuff: a comparison of ultrasonographic and arthroscopic findings in one hundred consecutive cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am, 82; 2000:498-504.

33. Levy O, Mullett H, Roberts S, Copeland S. The role of anterior deltoid reeducation in patients with massive irreparable degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:863-870.

34. Kempf JF, Gleyze P, Bonnomet F. A multicenter study of 210 rotator cuff tears treated by arthroscopic acromioplasty. Arthroscopy. 1999;15:56-66.

35. Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, et al. Arthroscopic débridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:743-748.

36. Klinger HM, Spahn G, Baums MH, Steckel H. Arthroscopic débridement of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears—a comparison of débridement alone and combined procedure with biceps tenotomy. Acta Orthop Belg. 2005;105:297-301.

37. Klinger HM, Steckel H, Ernstberger T, Baums MH Arthroscopic débridement of massive rotator cuff tears: negative prognostic factors. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg, 125; 2005:261-266.