Vaginal Masses

Synonyms/Description

Etiology

Vaginal Cysts

Vaginal Solid Masses

Ultrasound Findings

Differential Diagnosis

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

Figures

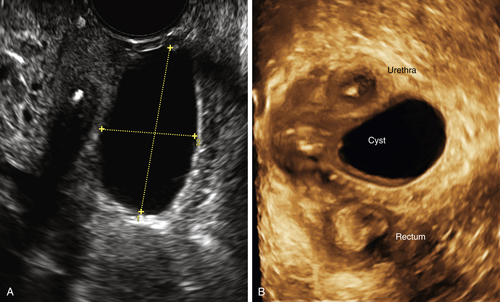

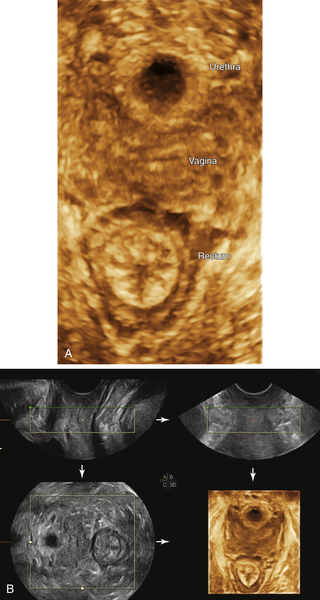

Figure V1-1 A and B, 3-D reconstructed view of the floor of the normal pelvis, showing the urethra, vagina, and rectum en face. B demonstrates the multiplanar view of the pelvic floor, showing the acquisition planes. The 3-D volume was acquired from the perineum and sweeping side to side. The A plane in the upper left-hand corner shows the acquisition view looking straight down the vagina. The B plane shows the same view at right angles from the A plane. The C plane is the reconstructed view of the floor of the pelvis, which is crucial to evaluating the perineal structures, including the length of the vagina and its relationship to neighboring structures.

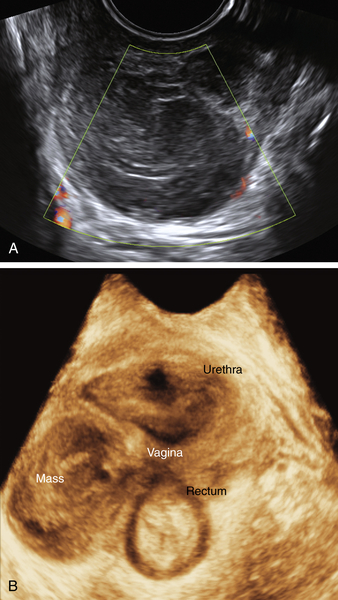

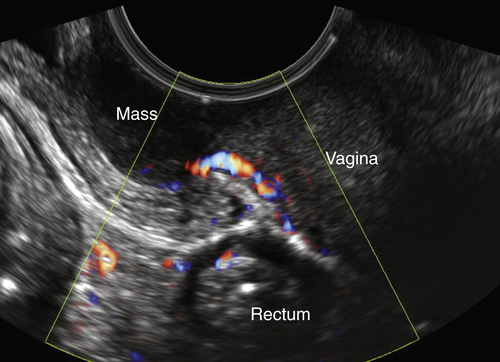

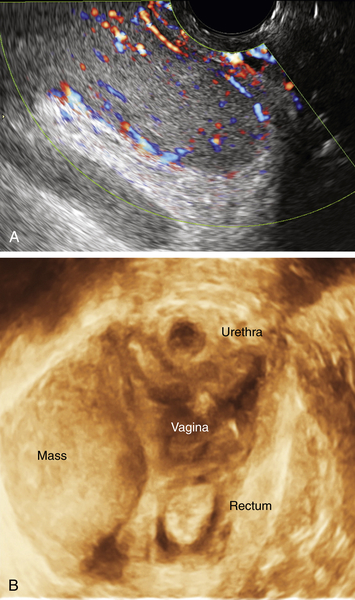

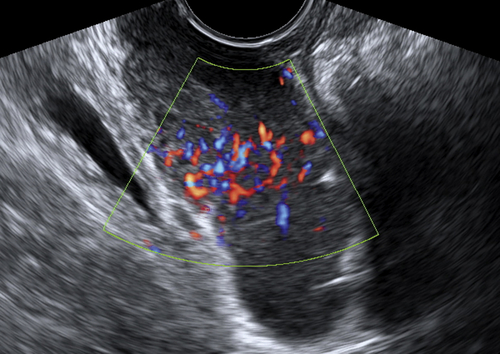

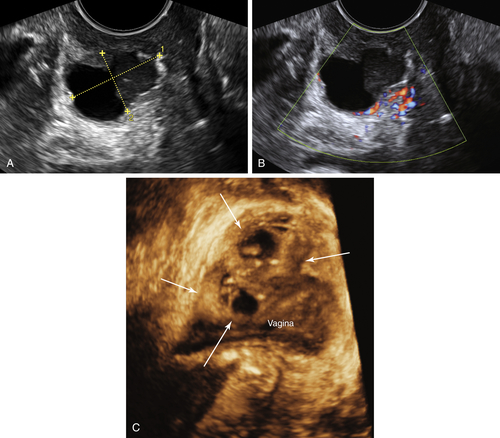

Figure V1-3 Urethral diverticulum. A and B, 2-D view of a complex cystic mass with irregular borders and internal debris. Note that the vascularity is only in the peripheral aspect of the mass. The mass was located anterior to the vagina and lateral to the urethra. The patient was quite symptomatic, particularly upon voiding. C, 3-D reconstructed view of a different case of a urethral diverticulum. Note the complex, multicystic mass anterior to the vagina where the urethra should be. The exact location of the urethra is obscured and likely encapsulated by this cystic mass, which was quite symptomatic.

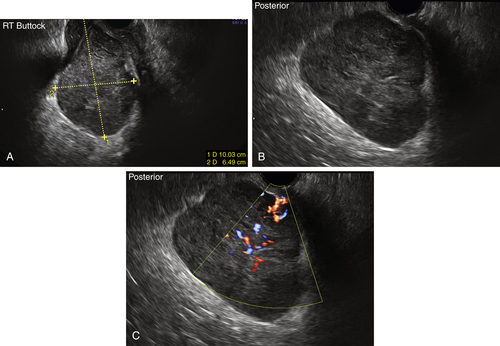

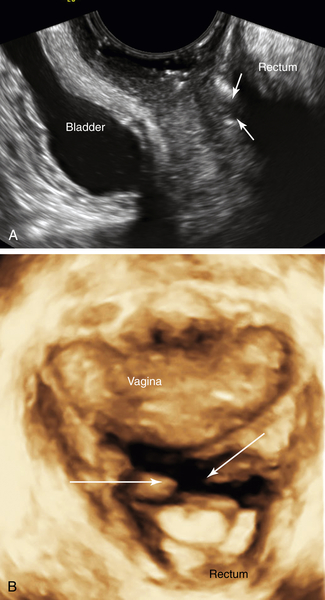

Figure V1-9 A and B, Recto-vaginal fistula. 2-D and 3-D views of the perineum looking down the vagina in a patient with Crohn’s disease who had clinical evidence of a fistula. Arrows demonstrate the location of the fistula, which was identified first on the 3-D reconstruction (B) and then recognized on standard 2-D imaging (A). An MRI done the same day had been read as negative.

Suggested Reading

Dai Y., Wang J., Shen H., Zhao R.N., Li Y.Z. Diagnosis of female urethral diverticulum using transvaginal contrast-enhanced sonourethrography. J Int Urogynecol. January 31, 2013 [Epub ahead of print].

Elsayes K.M., Narra V.R., Dillman J.R., Velcheti V., Hameed O., Tongdee R., Menias C.O. Vaginal masses: magnetic resonance imaging features with pathologic correlation. Acta Radiol. 2007;48:921–933.

Fletcher S.G., Lemack G.E. Benign masses of the female periurethral tissues and anterior vaginal wall. Curr Urol Rep. 2008;9:389–396.

Hwang J.H., Oh J.M., Lee N.W., Hur J.Y., Lee K.W., Lee K.J. Multiple vaginal Müllerian cysts: a case report and review of literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:137–139.

Kondi-Pafiti A., Grapsa D., Papakonstantinou K., Kairi-Vassilatou E., Xasiakos D. Vaginal cysts: a common pathologic entity revisited. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2008;35:41–44.