Synonyms/Description

None

Etiology

Cervical cancer accounts for the majority of cervical malignancies and is second to breast cancer in incidence worldwide. Approximately 85% to 95% of cervical cancers are squamous cell carcinomas and develop at the squamous-columnar junction.

Adenocarcinomas represent only 5% of cervical cancers and arise from glandular cells found in the endocervical canal. Squamous cell lesions of the cervix are typically detected early using conventional cytologic screening methods (Pap test) because they are easy to sample. The majority of endocervical glands are deep within the cervical canal, so detection usually occurs at more advanced stages of disease; hence they have a poorer prognosis than squamous cell cancers. The survival for stages I, II, and III cervical adenocarcinoma is 60%, 47%, and 8% compared with 90%, 62%, and 36% for squamous cell carcinoma.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the cervix is rare, accounting for 1% of all extranodal lymphomas. Clinically it may present as a large lobular vascular solid mass of the cervix. Metastatic disease, such as melanoma and breast, lung, and ovarian cancers, may also involve the cervix.

Malignant mixed Müllerian tumors and leiomyosarcomas occur more frequently in the uterine corpus, but may arise in the cervix in rare cases. Embryonal rhabdomyosarcomas typically occur in the pediatric age group.

Benign masses of the cervix include fibroids and polyps, which are similar in origin and appearance to their counterparts in the uterine corpus. Nabothian cysts are also commonly seen.

Ultrasound Findings

Cervical masses can obstruct the cervical canal and result in a hematometra, which may be the first sonographic sign of a cervical malignancy. Cervical carcinomas, especially squamous, are often subtle or undetectable sonographically as they can be quite small. As they grow, they appear as solid lobulated masses with abundant vascularity. Sarcomas and lymphomas are typically large solid vascular tumors when discovered. The appearance of these malignant tumors is nonspecific, although the excessive and disorganized blood flow within the tumor suggests a malignancy. Epstein and colleagues compared the sonographic characteristics of squamous cell and adenocarcinoma of the cervix. The ultrasound appearances of the tumors were all solid masses; however, 73% of the squamous cell carcinomas were hypoechoic, whereas 68% of the adenocarcinomas were isoechoic (p = 0.03). Mixed echogenicity was a nonspecific finding, and Doppler color flow was abundant in almost all the tumors of both types.

Benign masses of the cervix also tend to be solid sonographically, although the blood flow pattern seen with color Doppler tends to be different from that of the cancers. Polyps typically have a single feeding vessel, and are usually echogenic, sometimes containing a cystic center. Fibroids are solid masses with a similar appearance to those in the uterine corpus. They are well circumscribed, with acoustic shadowing, often with a pattern of stripes or swirls caused by these shadows. The blood flow in fibroids is variable although less abundant than in malignant lesions and more peripheral.

Nabothian cysts appear as very smooth and round, cystic, hypoechoic masses without any areas of Doppler color flow, and are extremely common, especially in women with previous pregnancies.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for a cervical mass includes the common entities such as a polyp or fibroid. If the mass is lobulated and highly vascular, a cervical malignancy such as a carcinoma, lymphoma, sarcoma, or metastatic tumor must be considered. A biopsy is necessary to arrive at a definitive diagnosis because these cervical malignancies have a similar sonographic appearance. Transvaginal ultrasound can also be helpful for staging of cervical cancers although MRI, CT, and PET/CT are typically used for these work-ups.

Clinical Aspects and Recommendations

The management of a sonographically detectable cervical mass depends on the etiology. Masses that are hypervascular or that appear atypical should be biopsied. However, simple punch biopsy may be inadequate, especially for tumors arising or metastasizing deep in the cervix. A bulky cervical non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma may present as an irregular, palpable, bulky mass, but a punch biopsy will often reveal normal squamous tissue. A cone or excisional biopsy is required in cases in which the initial biopsy does not correlate with the sonographic findings. Management then depends on the diagnosis. Malignancies are treated with multiple modalities, including, but not limited to, surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy. Asymptomatic fibroids do not typically require treatment, except in cases in which they may affect reproductive outcomes. When indicated, treatment is generally surgical. Cervical polyps often present with spotting and usually can be excised, although dilation and curettage may be required to get the entire stalk removed. Nabothian cysts are not pathologic, and thus no treatment is indicated.

Figures

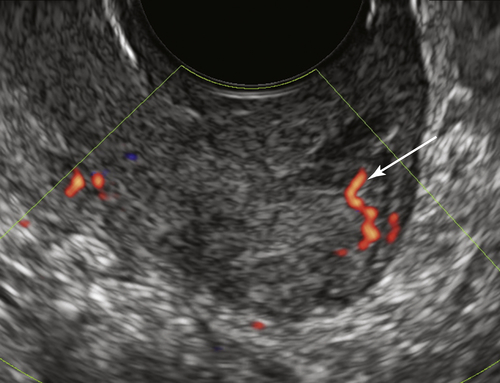

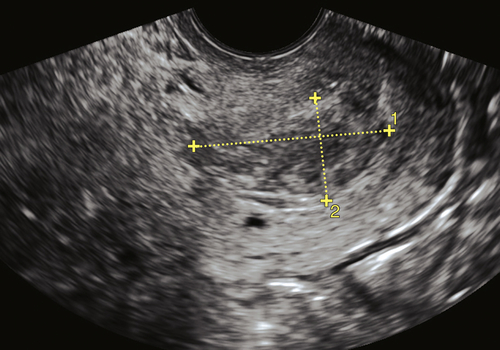

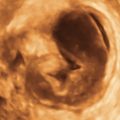

Figure C1-1 Small squamous cell carcinoma of the surface of the cervix, identified by the cluster of blood vessels (arrow) on the external os region.

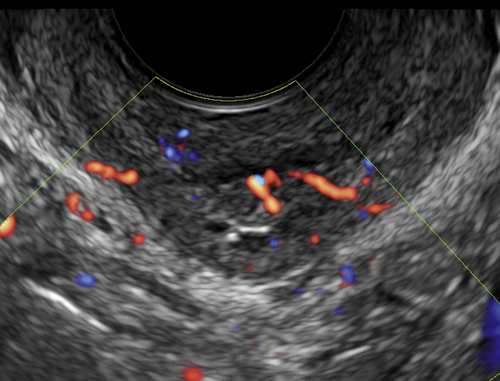

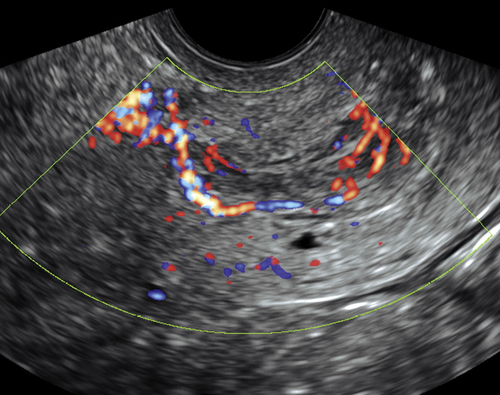

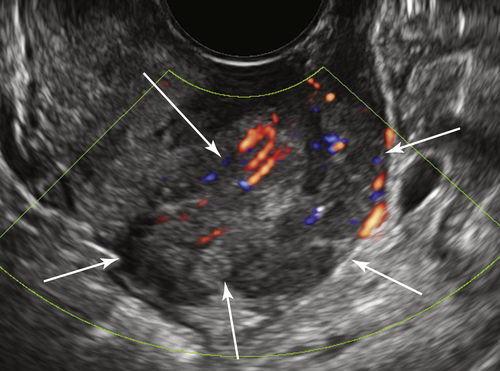

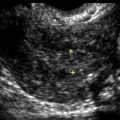

Figure C1-2 Transvaginal view of a large cervical tumor (arrows) with abundant blood flow, arising from the endocervical canal and protruding through the cervix. This proved to be an adenocarcinoma of the cervix.

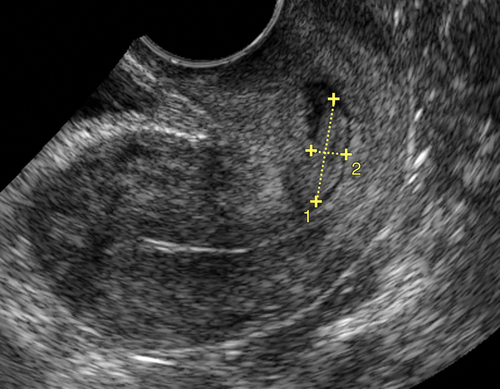

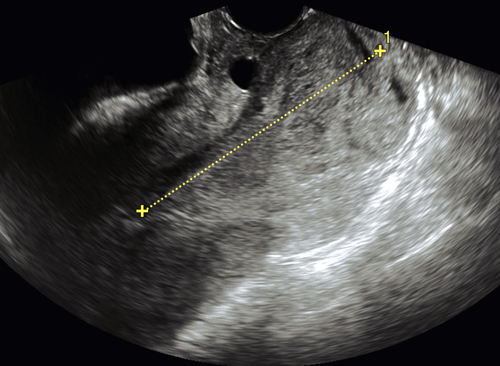

Figure C1-3 Cervical polyp originating from the lower uterine segment and protruding through the cervix. Note the feeding vessel.

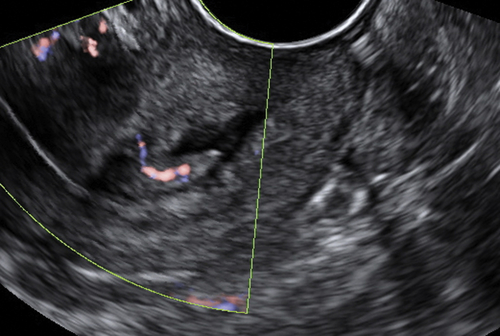

Figure C1-4 Small endocervical polyp with single feeder vessel.

Figure C1-5 Cervical fibroid. Note the round, well-demarcated mass on the side of the cervix.

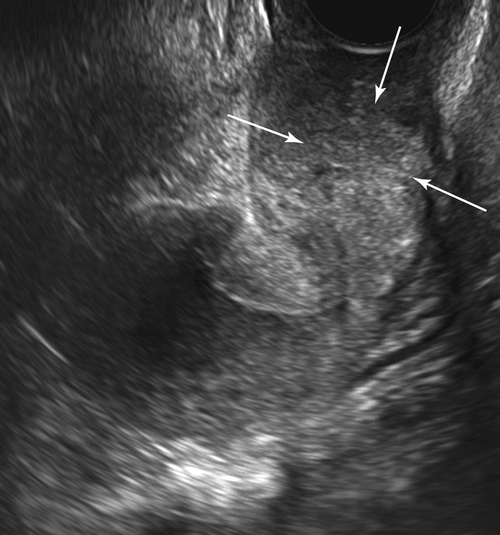

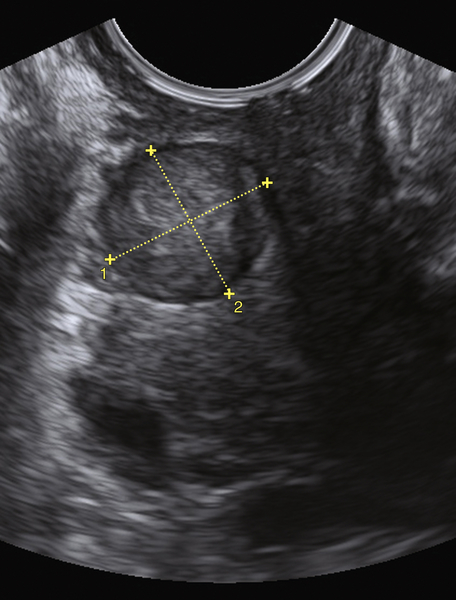

Figure C1-6 Cervical lymphoma. Note the large mass (arrows) with modest vascularity surrounding the entire outer aspect of the cervix.

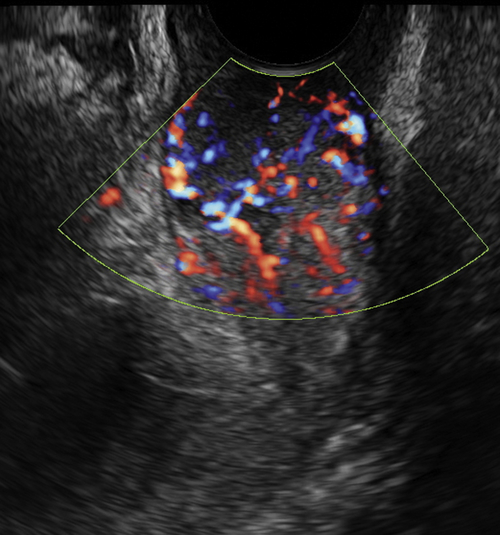

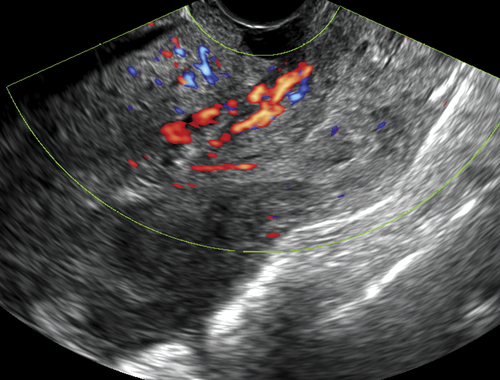

Figure C1-7 Large vascular mass protruding through the cervix. The appearance was worrisome because of the heterogeneity of the mass and the abundant blood flow. This mass proved to be a benign fibroid at surgery.