Chapter 44 MASS IN THE LIVER

APPROACHES TO THE LIVER MASS

Incidental liver mass in the well patient

With the widespread use of ultrasound for the investigation of a wide range of abdominal symptoms, focal liver masses are frequently identified. Most of these represent benign pathology, and further imaging is only required if there is doubt as to the nature of the mass on the initial study. Patients with a simple cyst can be reassured and no further investigation is needed. A recent study has shown that if a focal mass has the typical appearance of a haemangioma on ultrasound the risk of missing a malignant lesion is less than 0.5%, so further imaging is not required. Other focal lesions usually require further investigation, depending on the initial form of imaging employed.

BENIGN LIVER MASSES

Cavernous haemangioma

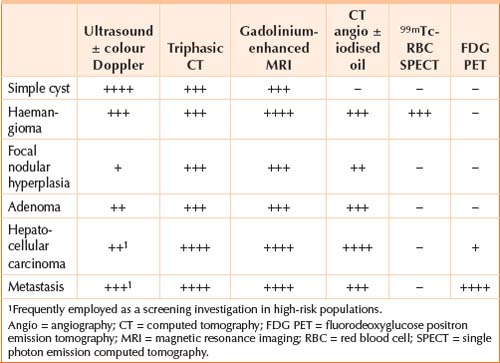

Cavernous haemangiomas are the most common benign hepatic tumour, occur in 5% of the population and are female predominant. On ultrasound they are well circumscribed, uniform, hyperechoic lesions without a peripheral halo. When found incidentally in the otherwise well patient, classical ultrasound features are usually sufficient to establish the diagnosis and further investigation or treatment is unnecessary. Atypical haemangiomas can present a diagnostic challenge but triphasic computed tomography (CT) or, preferably, gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) will confirm the diagnosis in the majority of cases and have largely replaced 99mTc-labelled red blood cell studies (Table 44.1).

Focal nodular hyperplasia

Focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) is a well circumscribed mass that typically displays a central stellate scar, a feature that is best seen with triphasic CT or gadolinium-enhanced MRI (Table 44.1). FNH is female predominant, usually asymptomatic and does not progress to malignancy. Ultrasound displays an isoechoic or hypoechoic lesion and colour Doppler may display vessels radiating outward from the artery within the central scar. Most lesions are less than 5 cm diameter and solitary. Occasionally differentiation from fibrolamellar HCC may be difficult.

Adenoma

Hepatic adenoma is an uncommon female-predominant benign liver mass with the potential for haemorrhage, rupture or malignant transformation. It is more common in women exposed to oral contraceptive steroids and men who have used anabolic steroids. Ultrasound appearance is variable, but adenomas are mostly isoechoic or hypoechoic with variable echodensity within the lesion. At triphasic CT adenomas are typically low density on pre-contrast images with rapid enhancement during the arterial phase, though differentiation from FNH and occasionally HCC is difficult (Table 44.1). Fat or blood products may be seen within the lesion on MRI. Surgical resection is recommended due to the significant complication rate associated with adenomas and the risk of misdiagnosis of HCC.

Simple cysts

Simple cysts occur in 2.5% of the population, are often multiple and appear on ultrasound as round or oval anechoic lesions with smooth, thin or imperceptible walls, showing posterior enhancement and no internal structure (Table 44.1). Usually no further investigation is required and the patient can be reassured as to the benign nature of the lesion.

Complex cysts

In contrast to simple cysts, complex cysts display internal echoes, irregular thick walls, thick septations more than 3 mm or mural nodularity on ultrasound. Differential diagnosis includes pyogenic abscess, hydatid disease and, rarely, neoplasms such as biliary cystadenoma and hepatic metastases. Further investigation is warranted, with the direction guided by associated clinical features.

MALIGNANT LIVER MASSES

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary malignant tumour of the liver, exhibits male-predominance and usually occurs on a background of chronic liver disease. Either triphasic CT or gadolinium enhanced MRI are the investigations of choice (Table 44.1), depending on availability and institutional preference; with the typical lesion demonstrating arterial enhancement followed by rapid contrast washout in the portal venous and later phases. MRI has the advantage of better differentiating between regenerative nodules, dysplastic nodules and HCC. Other imaging modalities, such as CT angiography with iodised oil, are reserved for equivocal lesions, and may assist in differentiation from regenerative or dysplastic nodules. A raised serum alpha-fetoprotein is present in 50% of patients and aids diagnosis if present. Fine needle aspiration of suspected HCC is to be avoided due to the risk of tumour seeding if there is potential for curative surgical resection or hepatic transplantation.

Metastases to the liver

After the lymphatic system, the liver is the most common site for metastatic cancer. Hepatic metastases are often first detected on ultrasound as multiple nodules of differing sizes with a hypoechoic halo usually involving both lobes of the liver. Solitary lesions are observed in 10% of cases. Large tumours may outgrow their blood supply leading to central necrosis. As hepatic metastases may be derived from a wide range of primary cancers, their appearance on imaging is quite variable. Most lesions are hypovascular and are most obvious as areas of reduced attenuation during the portal venous phase of a triphasic CT (Table 44.1), sometimes exhibiting peripheral ring-like enhancement. Hypervascular metastases are less common and include renal cell carcinoma, carcinoid, islet cell carcinoma, thyroid carcinoma, melanoma, neuroendocrine tumours and some breast carcinomas. Additional evaluation by way of MRI (Table 44.1) or (18F) fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG PET) may be undertaken if surgical resection or percutaneous ablation is being considered. Management is influenced by the nature of the primary cancer, if known, with colorectal metastasis being resected if feasible. For unresectable lesions, imaging-guided fine needle aspiration cytology confirms the diagnosis and may help guide cytotoxic therapy.

THE DIAGNOSTIC DILEMMA

Decision making not only includes reaching a diagnosis, but selecting patients with malignant disease who are candidates for liver transplantation or surgical resection as well as for less invasive procedures, including percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA), ethanol injection, cryogenic ablation, transarterial chemoembolisation (TACE) or 90Y microsphere embolisation.

American College of Radiology. ACR appropriateness criteria: liver lesion characterisation, and suspected liver metastases. Online. Available: http://www.acr.org/SecondaryMainMenuCategories/quality_safety/app_criteria/pdf/ExpertPanelonGastrointestinalImaging/LiverLesionCharacterizationDoc9.aspx

Choi BY, Nguyen MH. The diagnosis and management of benign hepatic tumors. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39:401-412.

Kinkel K, Lu Y, Both M, et al. Detection of hepatic metastases from cancers of the gastrointestinal tract by using noninvasive imaging methods (US, CT, MR imaging, PET): a meta-analysis. Radiology. 2002;224:748-756.

Leifer DM, Middleton WD, Teefey SA, et al. Follow-up of patients at low risk for hepatic malignancy with a characteristic hemangioma at US. Radiology. 2000;214:167-172.

Li D, Hann LE. A practical approach to analyzing focal lesions in the liver. Ultrasound Q. 2005;21:187-200.

Mortele KJ, Praet M, Van Vlierberghe H, et al. CT and MR imaging findings in focal nodular hyperplasia of the liver: radiologic-pathologic correlation. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:687-692.

Szklaruk J, Silverman PM, Charnsangavej C. Imaging in the diagnosis, staging, treatment, and surveillance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:441-454.

Taylor M, Forster J, Langer B, et al. A study of prognostic factors for hepatic resection for colorectal metastases. Am J Surg. 1997;173:467-471.