Chapter 22 Mass casualty, chemical, biological and radiological hazard contingencies

AIMS AND OBJECTIVES

Incidents involving mass casualties are infrequent. However, they have the potential to overwhelm usual health resources with very little notice. It is therefore important that contingencies are developed, tested and ready for immediate implementation. Such contingencies outline the responsibilities for overall medical control, coordination and effective casualty management in major emergencies and disaster situations. They include the procedures for triage, first aid and resuscitation, some of which require modification when resource availability needs to be rationed.

PHASES OF A DISASTER

The phases of disaster management are prevention, preparedness, response and recovery.

Prevention

The prevention phase concentrates on strategies that minimise the severity of an incident. It aims to cushion the severity, reduce the effects, minimise adversity and contain the impact of a disaster. Prevention strategies also include incorporation of lessons learned from previous experiences.

ADMINISTRATIVE AND LEGISLATIVE MANDATES

Very broadly these legislative frameworks provide for:

MEDICAL RESPONSE PLANS AND AGENCIES

Components of a state medical response

Agencies or organisations responsible for health

The health department ensures coordination of:

The health department has direct responsibilities as the control agency for:

The ambulance service

Pre-hospital medical coordination/disaster scene

Area medical coordinator (AMC)/senior field emergency medical officer

Central medical coordinator (CMC)

The CMC is usually located in the ambulance communications centre. The CMC’s role is to:

Site medical control

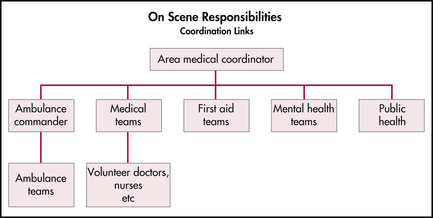

As an AMC or ambulance commander arrives on site, further assessments will be made and a joint medical command post established. All incoming medical responders report to the command post where tasks within the CCP are allocated. Further medical assistance required on site is requested through the central medical coordinator to avoid convergence and duplication of resources. A typical communication structure is outlined in Figure 22.1.

Life-saving procedures, such as airway management, immediate decompression of tension pneumothorax, arrest of haemorrhage, fracture stabilisation and relief of pain where necessary, may be the limit of medical assistance where medical resources are few. Thus effective triage or classification of casualties by a casualty collecting (ambulance) officer (CCO), medical officer or team leader from a medical team is essential.

Triage and reverse triage

Sieve

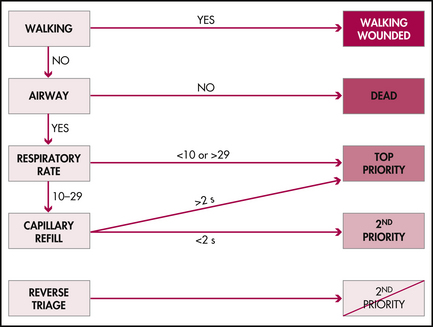

This triage method is used during the initial phase of managing mass casualties. It focuses on determining which patients will survive and channels resources to initially moving that cohort of patients from the scene to a casualty clearing post or station. Triaging in this manner is a repeated process to ensure refinement of urgency stratification and to respond appropriately to the ongoing evolution of a casualty’s injury complex and consequent physiology.

A standard clinical reasoning scheme for triage is outlined in Figure 22.3. SIEVE triage categories are as follows:

Table 22.1 Triage groupings and criteria for mass casualty situations

| Group | Priority | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red—priority 1 |

SORT

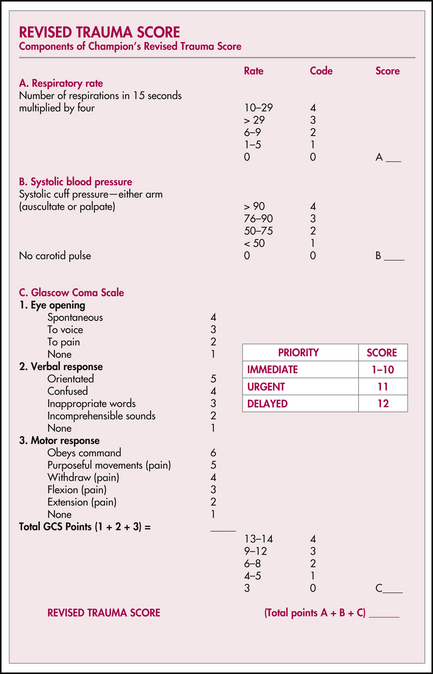

This method of triage is based on the Revised Trauma Score and is consistent with the Australasian Triage Scale, triage practices taught in emergency management of severe trauma (EMST), emergency life support (ELS), advanced paediatric life support (APLS) and major incident medical management and support (MIMMS) courses. It is identical to the practices employed by ambulance, first responder and other emergency medical services personnel for determining the time-critical patient. It is a repeated process that is dependent upon traditional ongoing patient observation.

SORT is generally implemented in the field utilising the Revised Trauma Score in order to rank physiological embarrassment and allocating an ordinal score. This assists with re-prioritisation or risk stratification of casualties. Scores of 1–10 are associated with the immediate category. A score of 11 identifies an urgent patient. A score of 12 or higher identifies casualties that can wait for delayed management (Figure 22.4).

Further refinement of triage can be assisted by attention to pattern of injuries or mechanism of injuries. However, in a trauma related mass casualty incident, a considerable number of patients may be classified as time-critical on mechanism of injury alone (Table 22.2). Close observation of this latter group is necessary. Although these patients are of lesser priority owing to normal physiological parameters or the absence of an identified pattern of injury, they are victims of major trauma, have sustained major forces and are at risk of significant and occult internal injury.

Table 22.2 Features defining victims of severe trauma or time-critical patients

| Pattern of injury | All penetrating injuries—head/neck/chest/abdomen/pelvis/axilla/groin |

| Blunt injuries— |

Hospital external disaster or emergency management plans—‘Respond Brown’

Such plans may also include the procedures for providing a trained and equipped medical team for casualty treatment at a disaster site. The provision of medical teams may reduce the emergency department effectiveness. Consideration is given to replacing or providing a team from another facility if the responding hospital is to continue to be a major casualty receiving hospital.

Certain first aid organisations such as St John Ambulance and the defence forces are also able to provide medical teams on request. Some base hospitals in rural regions also have the capability to provide such teams, with smaller hospitals having a reduced capability.

Phases of the external disaster plan

Standby

An emergency control centre (ECC) is established in the designated area. The ECC becomes responsible for the management of all aspects of the external disaster as it affects the hospital.

A representative list of support personnel and departments to be notified in the standby phase is outlined in Table 22.3. Notification is dependent upon the nature of the incident. For example, for a chemical hazard it may be decided not to advise the senior surgical staff.

| Medical staff on duty or on call |

Emergency department response

Call-in and notifications

Key clinical staff, clinical departments and management staff placed on standby are advised of the escalation (Table 22.3). Clinical staff are initially summoned to the emergency department and prepared to receive casualties.

Triage and triage officers

It is preferable for the the triage role to be undertaken by a senior doctor experienced or knowledgeable in the SORT and SIEVE methods of disaster triage. There is also an ongoing obligation to continue triage of non-disaster patients. It may be elected to simply use the Australasian Triage Scale with reverse triage of expectant cases designated as urgent.

Medical staff

It is preferable for emergency department doctors to be allocated to work in specific zones.

Additional medical officers may be requested through the emergency control centre.

An anaesthetist assists with urgent airway intervention, referrals and pre-operative assessments.

Junior medical staff may be utilised to manage ambulatory patients in designated satellite areas.

A doctor, preferably of three or more years’ experience, or senior nurse may be allocated to the care of extremely severely injured patients with low probability of survival—the expectant category. Intensive efforts to resuscitate these patients may jeopardise the survival of large numbers of other casualties because of an excessive drain on resources. Supportive and palliative care only should be given, until resources are available to commence more vigorous resuscitation, if appropriate.

In-hospital responses

The management of in-hospital responses and executive management issues are beyond the scope of this chapter. However, Box 22.1 identifies the other departments and resource areas that contribute to the overall response.

Box 22.1 Hospital-wide services necessary for external disaster plan

Departments and services contributing to external disaster responses:

Receiving and non-receiving wards

Supply and materials department

Central sterilising supply department

Engineering and facilities department

Management of families of disaster victims

CHEMICAL, BIOLOGICAL AND RADIOLOGICAL HAZARDS

Mode of presentation

Education of all staff in recognising a contaminated or CBR-hazard-exposed person is necessary in order to minimise the risk of emergency department exposure and contamination. Self-presentation prior to notification by emergency services agencies is common in chemical incidents. Occasionally, emergency services may be unaware of the incident. In this situation the health service has a system initiation function. In biological incidents, there is often a trickle followed by an epidemic flood of patients. Radiological incidents may involve burns, the consequences of initial radiation illness or the management of ongoing radioactivity.

Chemical agents

Blood agents—the cyanides

These agents impair cellular function by uncoupling oxidative phosphorylation.

Biological hazards

Patients exposed to microbiological agents may be recognised when a number of patients present with unusual similar symptoms or clinical signs. Alternatively an influx of patients with similar symptoms may present with diagnostic refinement identifying a common broad illness such as pneumonia with isolation of an unusual causal agent. Other dilemmas include when to immunise and when to definitively treat. These decisions must be made in conjunction with infectious disease physicians and public health agencies. Rationalisation of available therapeutic substances is a logistical problem. The principles of managing this issue are no different to those of disaster triage and reverse triage. However, within this context, development of inclusion and exclusion criteria is more relevant. The impact of the espouser on hospitals is likely to increase the workload of laboratory facilities in initial identification and ongoing examinations for isolation of infective agents or bacterial endotoxins and exotoxins.

Radiological hazards

Prodrome

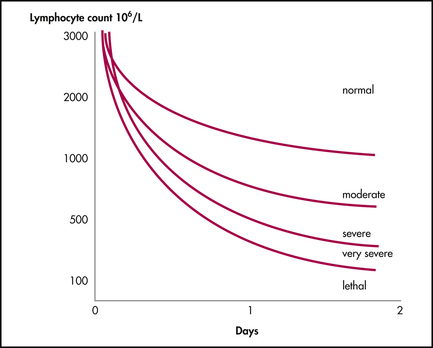

Initial symptoms often appear within 6 hours of exposure. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, anorexia and general malaise. Treatment is largely symptomatic and supportive. A 48-hour lymphocyte count and chromosomal analysis of lymphocytes for dicentric fragments are predictors of likely bone marrow suppression and haempoietic syndrome (see Figure 22.5).

Figure 22.5 Lymphocyte count as a guide to severity of haempoietic syndrome

Reproduced with permission from Emergency management practice manual 3: health aspects of chemical, biological and radiological hazards. Provisional edn, In: Australian emergency manuals series, part 3. Emergency Management Australia; 1999

Manifest illness

The symptoms of the gastrointestinal syndrome are similar to those of the prodrome phase with additional problems of diarrhoea, fever and gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Bowel perforation and septicaemia are complications of severe illness. Treatment is supportive with intravenous fluid resuscitation, dehydration and parenteral nutrition

The cerebral syndrome comprises nausea, vomiting, cardiovascular instability, confusion, ataxia, seizure and loss of consciousness. There is a high mortality within 24–48 hours.

Goals of emergency department management of CBR exposure

The emergency department goals are to:

Personal protective equipment (PPE)

There are various safety standards of protective equipment. Hospitals generally require safety standard C equipment. The suggested contents of a level C PPE kit are outlined in Box 22.2.

Isolation areas

Hot zone

The hot zone is an area of contamination. For practical purposes, this is an isolation area for dealing with contaminated casualties. In selecting an appropriate area for the hot zone, consideration needs to be given to wind direction, slope for run-off, access to water and drainage, ability to provide screening for privacy, traffic management and proximity to the emergency department.

Warm zone

The warm zone is a buffer area between hot and cold zones to minimise cross-contamination.

Decontamination

For safety reasons, only those staff designated as members of the decontamination team wearing full PPE are permitted to decontaminate patients. If protective respiratory equipment is required, only staff trained in the equipment are to be deployed.

The following points serve as a guide to effective patient decontamination:

Substance identification

Chemical substances may be identified using:

Radiation hazard identification may have already been advised by the relevant public health and environment protection agencies. However local nuclear medicine departments, especially those associated with radiotherapy treatment centres, may initially be of assistance. It is preferable that a radiation physicist assist with on-site assessment of patients and the local environment for radioactive contamination.

Decontamination teams

Colour-coded role-specific action cards outlining team roles should be worn around the neck.

Clean-up and decontamination of hot zone equipment

Hot zone equipment may be separated into two groups, a chemical/disaster box and supplementary equipment, as outlined in Table 22.4.

Table 22.4 Suggested equipment lists for decontamination areas

| Chemical disaster box equipment |

|---|

|

• Personal protective equipment—disposable barrier suit, overshoes, nitrile gloves and respirator with disposable filter and air hose

|

| Other equipment |

|---|

Clinical and related wastes

The underlying principles for the treatment and disposal of clinical and related wastes are the health and safety of personnel and the public and the minimisation of overall environmental impact.

Chemical exposure register

All staff, including visiting emergency service personnel, and patients involved in contaminated areas must be listed on the register. The minimum details required in the register include, name, hospital record number, designation and injuries sustained. Contact details of involved staff are recorded to ensure timely access if additional follow-up is required.

A tag stating the person has been exposed to a radiation, biological or chemical hazard and the substance involved is attached to the patient in the form of a wrist band. It is worn for a predetermined time, usually 48 hours in the case of a chemical exposure.

Beeching N.J., Dance D.A.B., Miller A.R.O., et al. Biological warfare and bioterrorism. BMJ. 2002;324:336-339.

Bradt D., Abraham K., Franks R. A strategic plan for disaster medicine in Australasia. Emergency Medicine. 2003;15:271-282.

Degg S. Chemical burns. Toxic chemical incidents. A Symposium conducted at the Australia Disaster College. Mt Macedon: Victoria; 1997.

Emergency Management Australia. Emergency management practice manual 2: safe and healthy mass gatherings, 1st edn. Emergency Management Australia; 1999. Australian emergency manuals series, part 3

Emergency Management Australia. Emergency management practice manual 3: health aspects of chemical, biological and radiological hazards. Provisional edn. Australian emergency manuals series, part 3. Emergency Management Australia; 2000.

Evison D., Hindsley D., Rice P. Chemical weapons. BMJ. 2002;324:332-335.

Hodgetts T.J., Mackway Jones K., editors. (Advanced Life Support Group). Major incident medical management and support, the practical approach, 2nd edn., London: BMJ Books, 2002.

Holmes J.L., Mark P.D. Medical planning and care in radiation accidents. Emergency Medicine. 1991;3(3):136-148. [Supp]

Koehlerr G. Hazardous materials medical management protocols, 2nd edn. California EMS Authority; 1991.

Medical Research Institute of Chemical Defence. Medical management of chemical casualties handbook, 2nd edn. Maryland: US Army; 1995.

Office of the Surgeon General. US Army. NBC Domestic preparedness training hospital provider course. Maryland: US Army; 1997.

South Australian Metropolitan Fire Brigade website: http://www.mfs.vic.gov.au.

Tan G.A., Fitzgerald M.C.B. Chemical biological radiological (CBR) response: a template for hospital emergency departments. Med J Aust. 1997;177:196-199.

Victorian Metropolitan Fire Brigade website: http://www.mfs.vic.gov.au.

Parts of this chapter were developed from the following documents:

Canestra J, Jones S, Wassertheil J, Johnstone R (Frankston Hospital External Disaster Committee), eds. Respond brown—external disaster plan. Victoria, Australia: Peninsula Health; 1999.

Jones S., Smith M., editors. Hazardous substance management. Victoria, Australia: Peninsula Health, 2000.

The section on radiation illness has been largely developed from: Holmes JL and Mark PD. Nuclear incident medical management. In: Emergency management practice manual 3: health aspects of chemical, biological and radiological hazards. Provisional edn. Australian emergency manuals series, part 3. Emergency Management Australia; 1999.