Martius Fat Pad Transposition and Urethral Reconstruction

Martius Fat Pad Transposition

Transposition of a labial fat pad with or without the bulbocavernosus muscle has been used to facilitate closures of fistulas involving the anterior and posterior vaginal wall. The procedure yields tissues that can fill in dead space and provide an excellent blood supply. The fact that this operation does not alter the anatomy of the vulva and is cosmetically pleasing is also important.

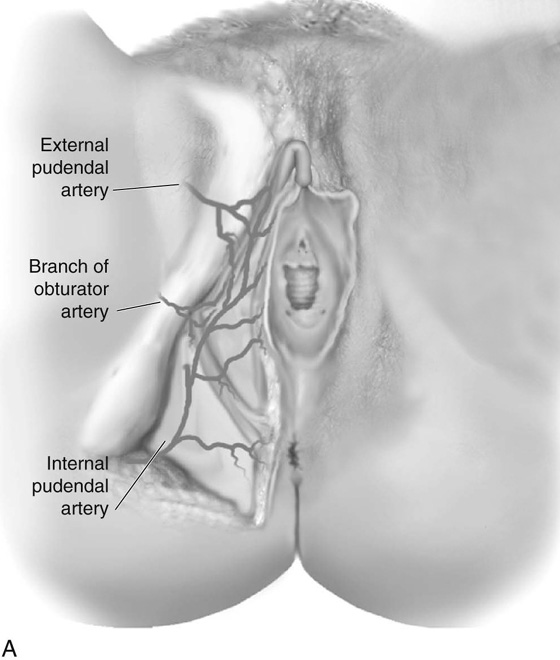

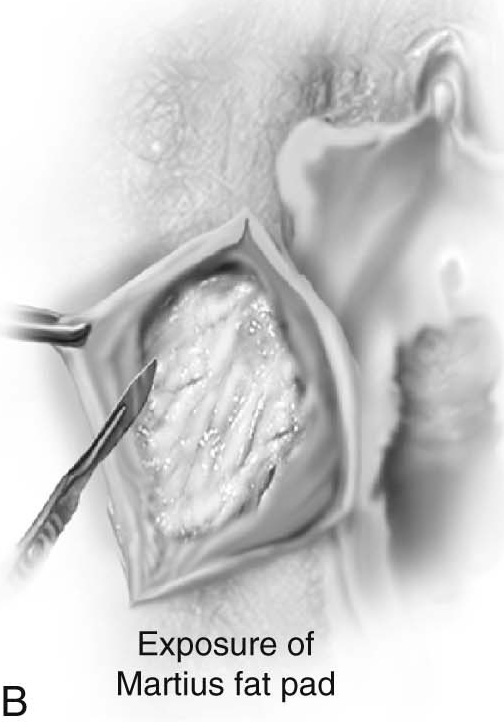

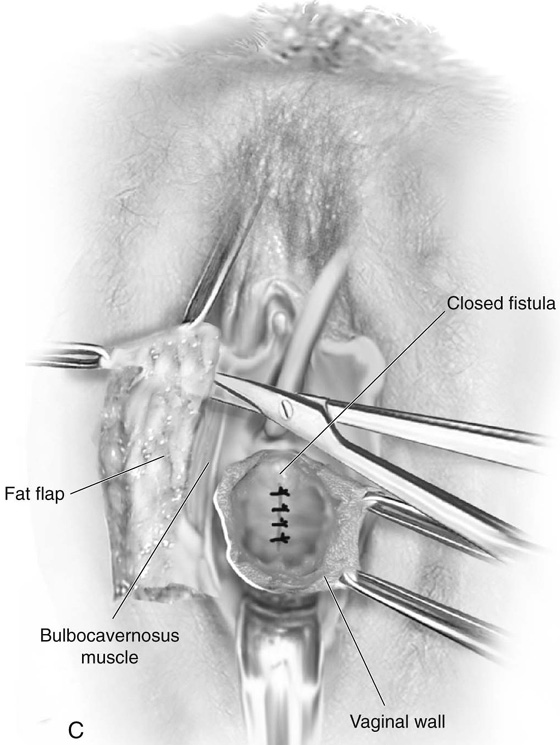

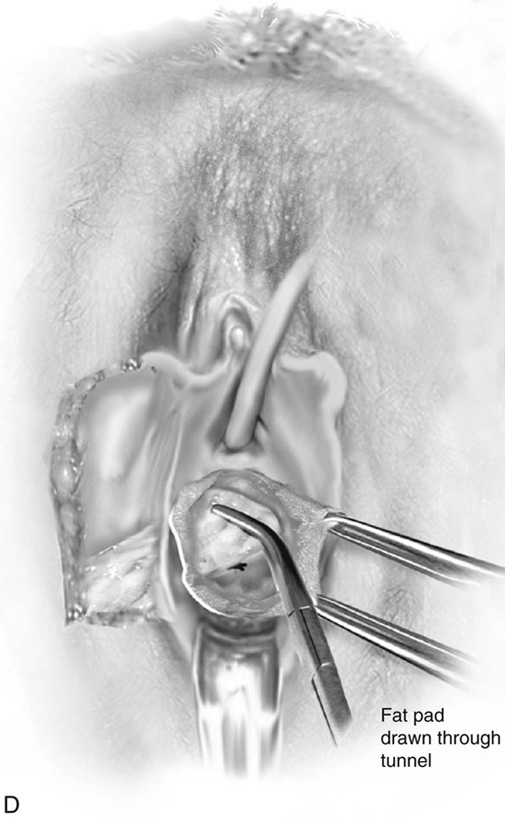

Fig. 85–1A demonstrates the abundant blood supply to the labial fat. It has been empirically stated that the majority of the blood supply comes from the inferior direction (internal pudendal artery); thus the detachment of the fat should be anterior. Our dissections and experience with the procedure would indicate that sufficient blood supply is present from both directions; thus detachment should be at the discretion of the surgeon and more related to the anatomic location of the defect in the vagina. The procedure begins by marking an incision over the labial fat. The fat pad is mobilized on each side. After the vaginal dissection has been completed, a long curved clamp is passed medially into the vaginal incision, thus creating a tunnel that the fat pad will pass through to reach the vaginal area. The fat pad is then detached either anteriorly or posteriorly and passed into the vaginal area and fixed with delayed absorbable sutures. The vaginal and labial incisions are closed without tension (see Figs. 85–1 and 85–2).

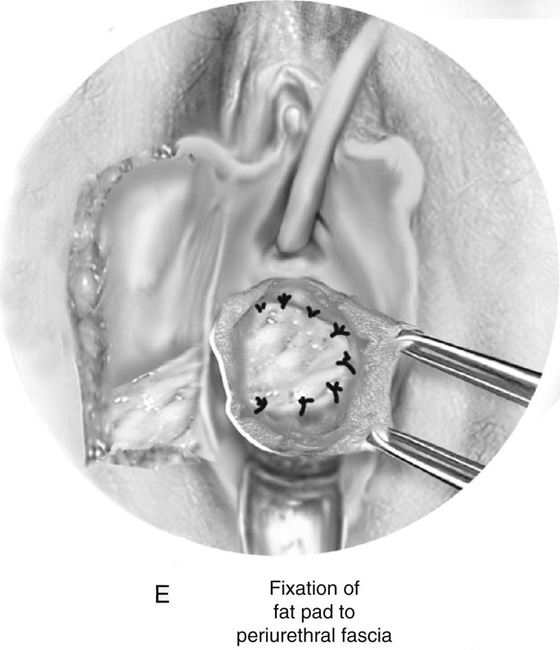

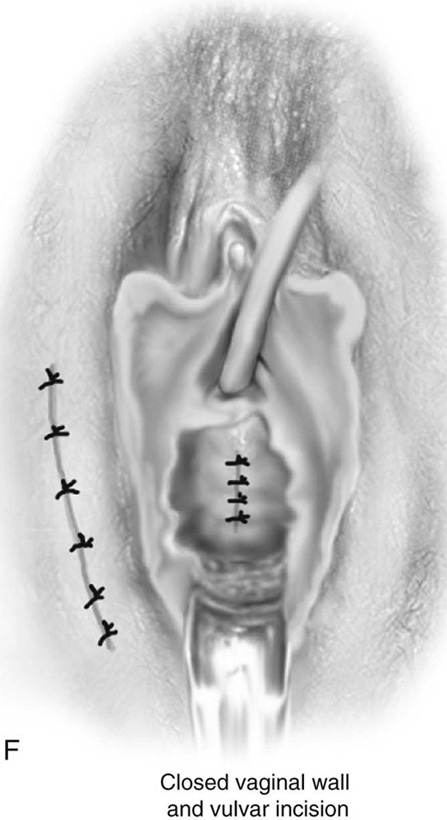

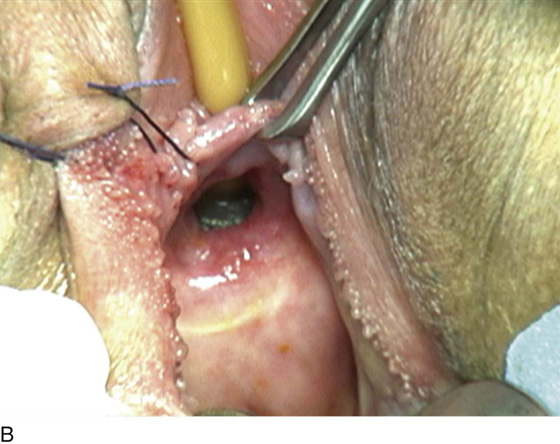

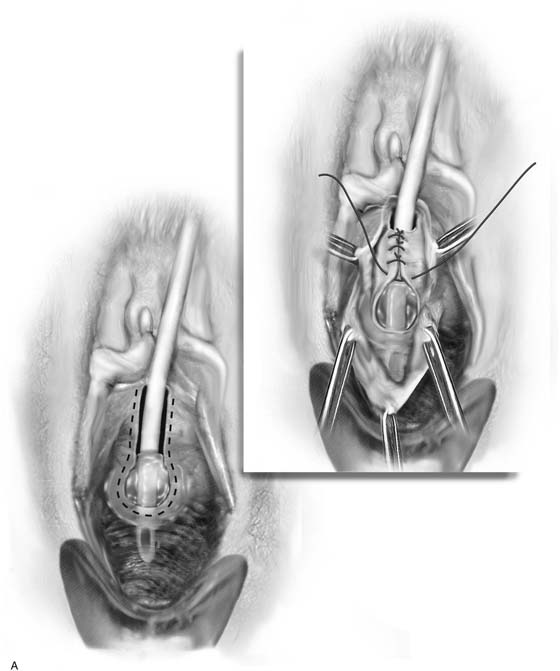

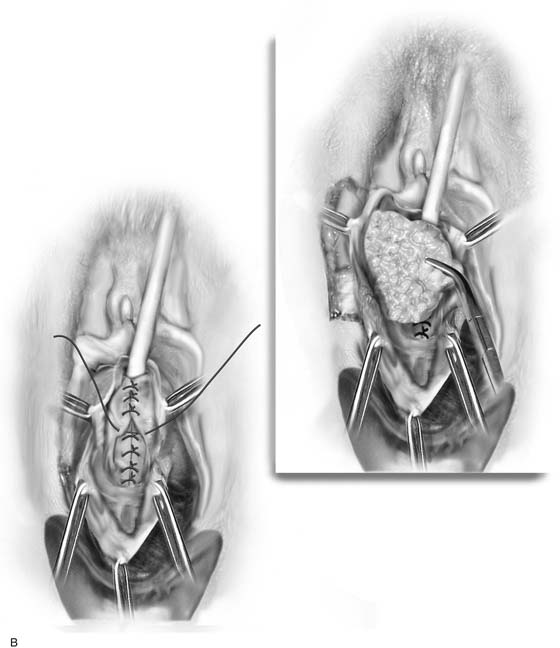

FIGURE 85–1 Technique of Martius fat pad transposition. A. Blood supply to the labial fat. B. Exposure of the fat pad via labial incision. C. Mobilization of fat. D. Anterior detachment of the fat pad with tunneling into the vaginal incision and fixation of the fat pad over the closed urethrovaginal fistula. F. Closure of the vaginal and labial incisions.

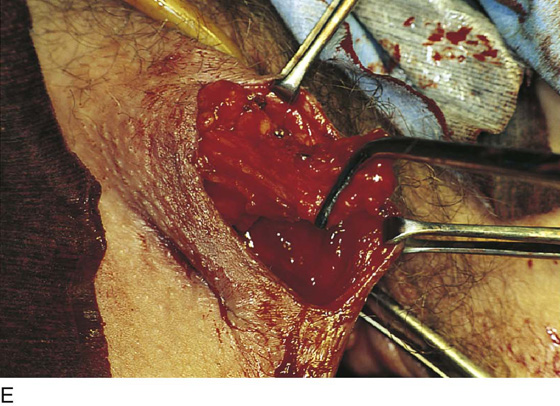

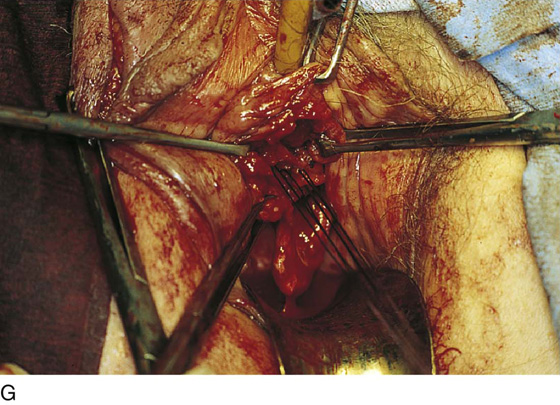

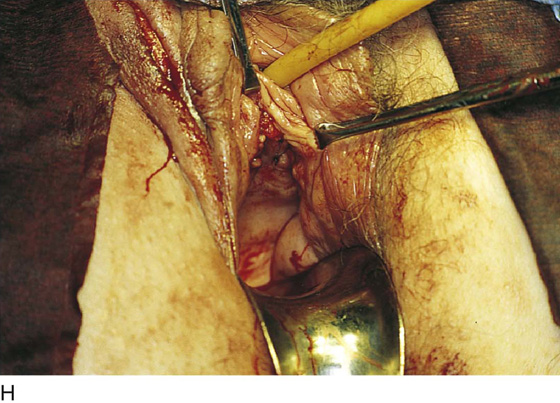

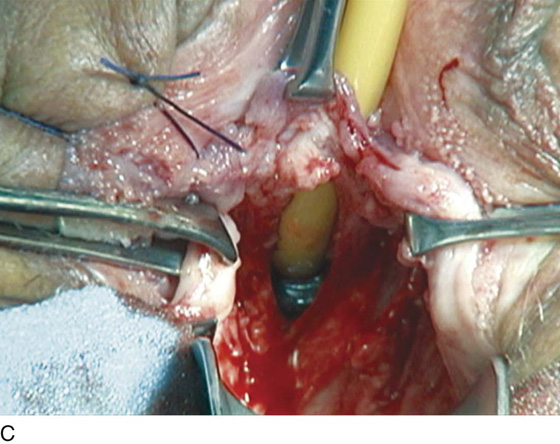

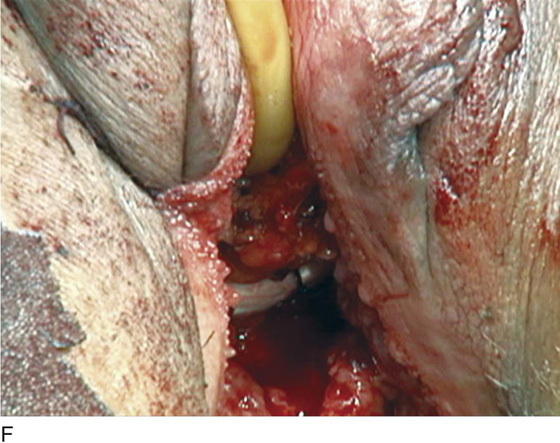

FIGURE 85–2 Technique of labial fat pad transposition. A. Site of the labial incision. B. Mobilization of skin off of the fat pad. C. Mobilization of the fat pad. D. A long clamp is used to tunnel under the skin into the vaginal incision. E. The labial fat pad is detached posteriorly. F. The labial fat pad is transposed into the vaginal incision. G. The labial fat pad is fixed into place with delayed absorbable sutures. H. The labial and vaginal incisions are closed.

Urethral Reconstruction

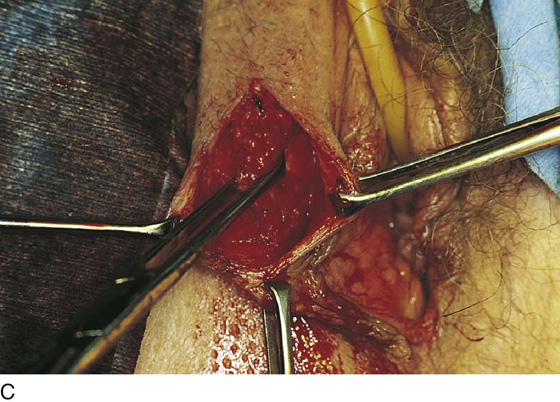

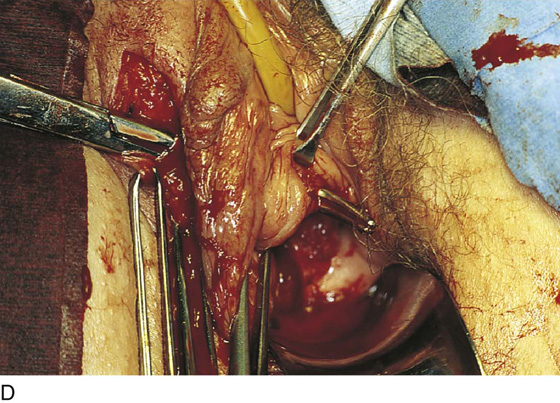

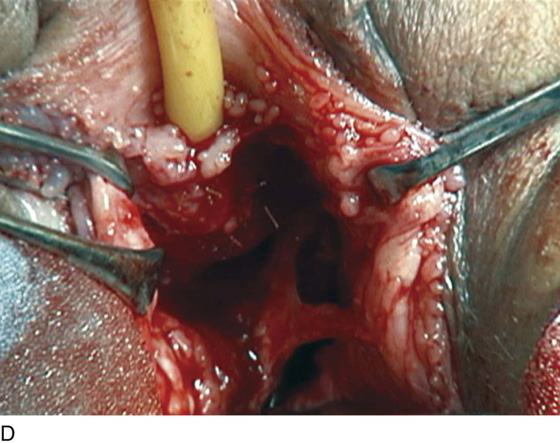

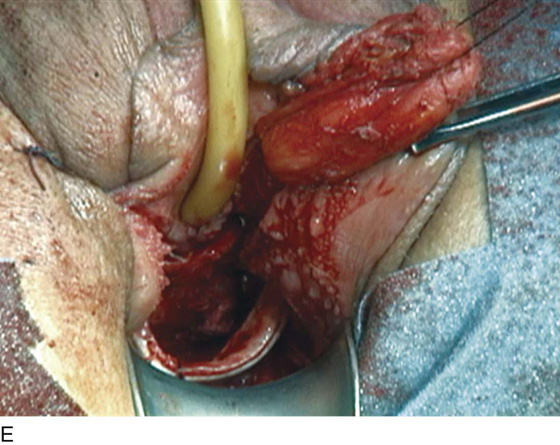

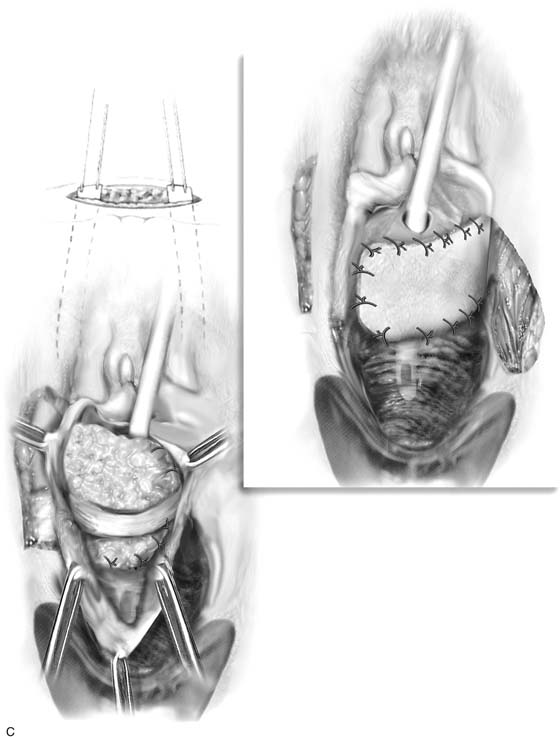

Repair of a damaged urethra is one of the most challenging problems in vaginal surgery. Indications for urethral reconstruction can include congenital abnormalities, radiation, multiple previous surgeries, and pelvic trauma. The goals of the surgical correction include creation of a continent sphincter mechanism, construction of a conduit for the urine to flow in a normal location, and covering the area with fresh vascularized tissue to avoid subsequent breakdown or fistula formation. In patients who have loss of a major portion of the posterior urethra, urethral reconstruction may be difficult, and normal urinary function, even in what appears to be a well-constructed urethral tube, is very unpredictable. The patient in Fig. 85–3 initially presented in her early thirties with a congenitally short urethral tube and an ectopic ureter implanting into the midportion of the urethra on the right side. The patient underwent a reimplantation of her right ureter (which was her only ureter) and a suburethral sling procedure. She presented approximately 2 years following this procedure with a complete breakdown of the anterior vaginal wall and loss of the entire posterior wall of the urethra, extending up into the region of the trigone (Fig. 85–4A, B). The basic principles of the repair are very similar to those of urethrovaginal fistula repair. In this situation an incision is made in the anterior vaginal wall adjacent to the margins of the defect. The vaginal wall is widely mobilized laterally to well beyond the pubic ramus. The retropubic space is entered bilaterally on each side to facilitate mobilization of the urethra. Once the vaginal mucosa has been mobilized laterally and the urethra has been mobilized as much as possible, the urethral tube is reconstructed. Usually the closure of the urethral tube is done over a No. 10 or 12 F urethral Foley catheter. This permits accurate approximation of the free edges of the roof of the urethra and the reconstruction of the tube. The sutures are placed in an interrupted fashion with 4-0 delayed absorbable sutures positioned extramuscosally. Ideally, the initial suture line should be followed by a second layer approximating the periurethral tissues to aid and support the initial suture line. A third layer of tissue, usually pubocervical fascia, is then mobilized from the inside of the vaginal wall. Since this is commonly very damaged tissue, a vascular pedicle in the form of a Martius fat pad is usually indicated. In patients who have a slough of the entire urethra including the bladder neck, it is necessary to attempt to preserve a continence mechanism, which is usually accomplished by the placement of a suburethral sling. Usually patients with a linear loss of the urethral floor also have loss of a significant portion of the anterior vaginal wall, and thus at the completion of the reconstruction it is impossible to cover the area with vaginal wall without creating significant unwanted tension. In these cases the size of the defect is accurately evaluated and an appropriate tongue of tissue from the labia minora is identified to be incised and swung into the vagina to replace the anterior vaginal wall. This fibro-fatty flap is usually hinged anteriorly. Usually a U flap is made and the base of the U is developed, mobilized and sutured to the edges of the vagina, thus covering the defect in the anterior vaginal wall. The site of the graft is then closed by approximating the skin edges with 4.0 delayed absorbable sutures (see Figs. 85–3 and 85–4).

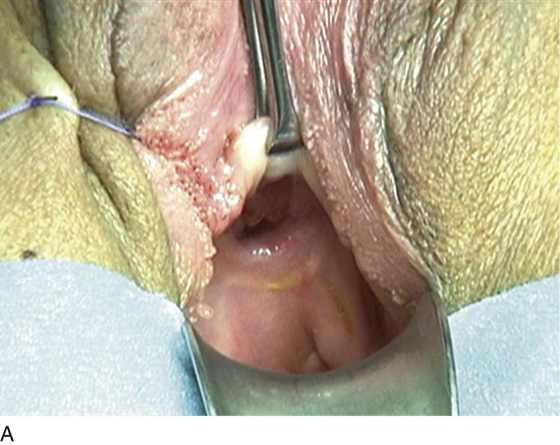

FIGURE 85–3 A. A vaginal view of a patient who has suffered complete linear loss of the posterior urethra. B. With a Foley catheter in place, one can see that the loss of tissue extends up into the trigone of the bladder. C. The initial dissection involves freeing and mobilizing the anterior wall of the vagina from the posterior wall of the urethra in preparation for layered closure of the posterior wall of the urethra. D. The urethra has been closed with interrupted 4-0 absorbable sutures, and the urethra has been mobilized completely to the inferior pubic ramus on each side to facilitate this closure in a tension-free fashion. E. A layer of fascia has been mobilized off the vaginal wall, laid across the posterior urethra, and sutured in place. F. A Martius fat pad has been transposed from the right labial area. It is sutured in place across the entire posterior urethra. A cadaveric fascia lata sling has been placed at the anatomic level of the proximal urethra. G. A skin flap from the left labia has been mobilized and sutured into the anterior vaginal wall to close the defect.

FIGURE 85–4 Urethral reconstruction. A. The dashed line depicts the location of the initial incision. Once the vagina is completely mobilized off the urethra and bladder, the defect is closed over the catheter with interrupted 4-0 delayed absorbable sutures. B. A second layer of interrupted sutures is placed to reinforce the initial layer. If possible, a third layer of pubocervical fascia is then placed over the urethral closure. This is followed by the placement of a Martius fat pad to act as a vascular pedicle for this damaged tissue. C. A pubovaginal sling is commonly placed at the level of the proximal urethra in the hope of preserving continence. Because many of these cases are associated with loss of most of the anterior vaginal wall, it is not uncommon that a labial skin flap is required to close the defect in the anterior vaginal wall in a tension-free fashion.