Mandible-First Analytic Model Planning for Orthognathic Surgery

Immediate presurgical records include current dental impressions of the maxillary and mandibular arches; accurate bite registration in centric relation (CR); a face-bow registration; and the recording of specific facial measurements, including deviations from normal. The dental models are placed on a semi-adjustable articulator for further analysis, and they are then used to complete analytic model planning.1,2,10,13,15,39,40 Acrylic splints are fabricated and used intraoperatively to further ensure the reliable execution of the predetermined reorientation of the maxilla and mandible to achieve facial aesthetic and functional objectives.

Although the making of clinical decisions about the preferred aesthetic repositioning of the jaws remains both an art and a science (see Chapter 12), the technical aspects of model planning should be precise and consistent. Analytic model planning and the use of prefabricated splints continue to represent the standard of care for bimaxillary and segmental maxillary osteotomies.6,14,17,52

Despite the benefits of this time-honored model planning approach, there is the potential for the introduction of error. For example, if an inaccurate CR bite registration is obtained from the patient preoperatively. The surgeon’s ability to obtain an accurate and reproducible bite registration in CR during the immediate presurgical clinical examination, during the occlusion of the dental models on the articulator in the laboratory, and when using the splints in the operating room is essential to avoid errors when standard analytic model planning is employed.5,12,13,17–28,32,33,35,36,53

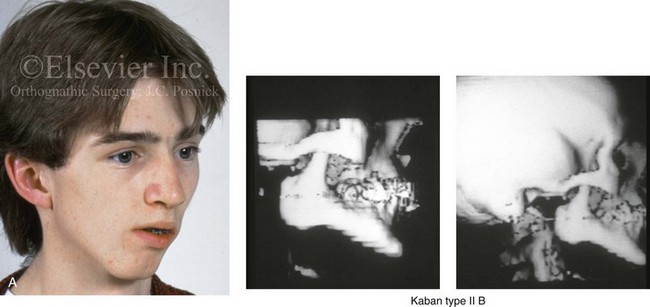

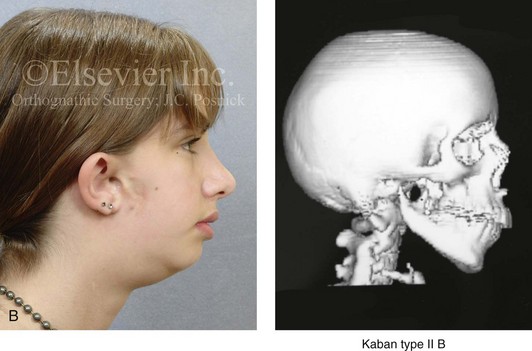

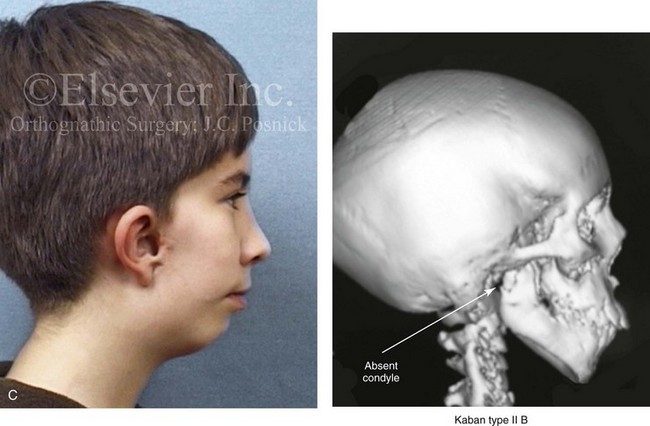

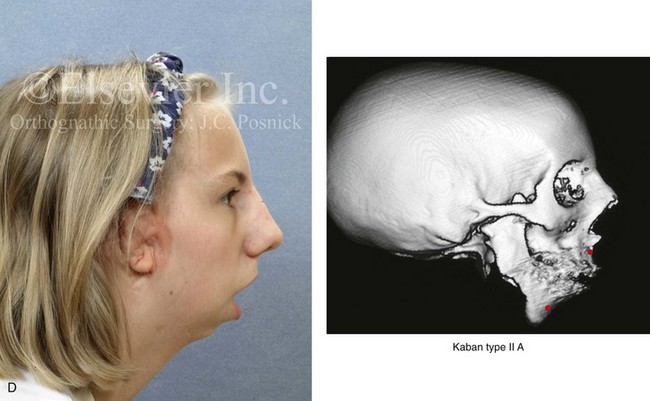

There are specific clinical settings in which the obtaining of an accurate and reliable CR can be problematic.8,11,34,37,39,52 Examples include the following individuals: 1) those who are missing a condyle after tumor resection 2) those with severe atrophy of the condyle after trauma and 3) those with specific syndromes in which the condyle-ascending ramus is aplastic (e.g., Treacher Collins syndrome, or hemifacial microsomia with Kaban type IIB or III malformation; see Chapters 27 and 28) (Fig. 14-1) For those patients with an unreliable CR, a “mandible-first” approach to analytic model planning is required.

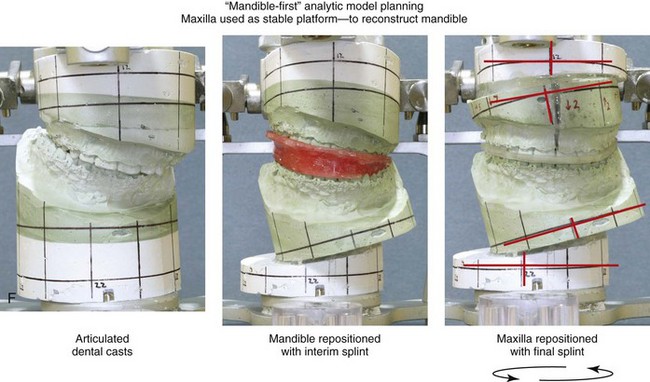

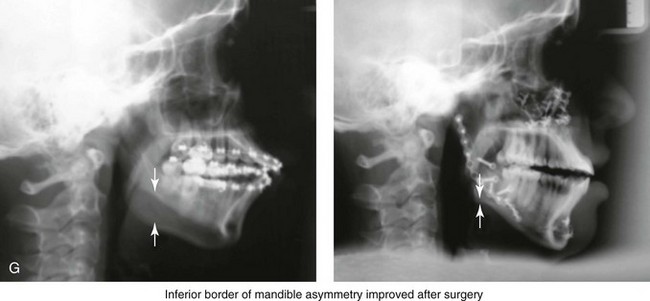

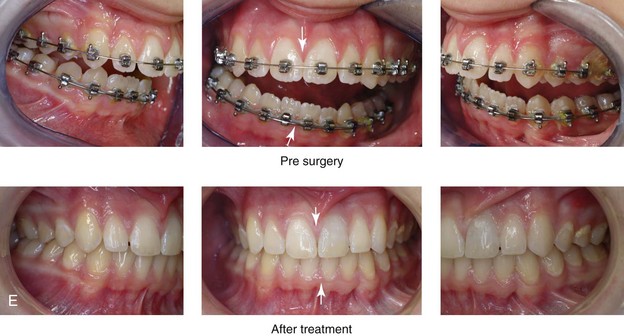

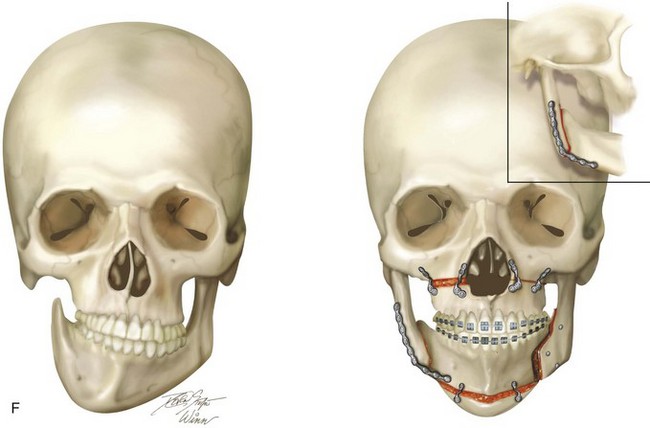

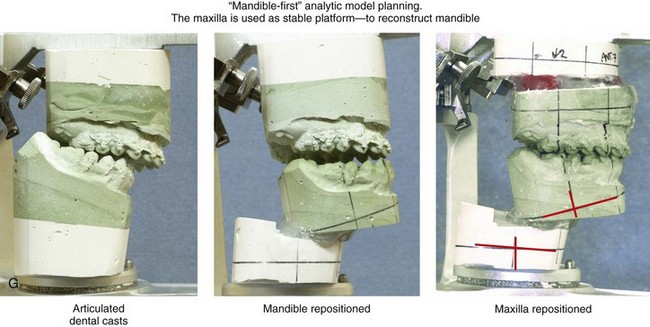

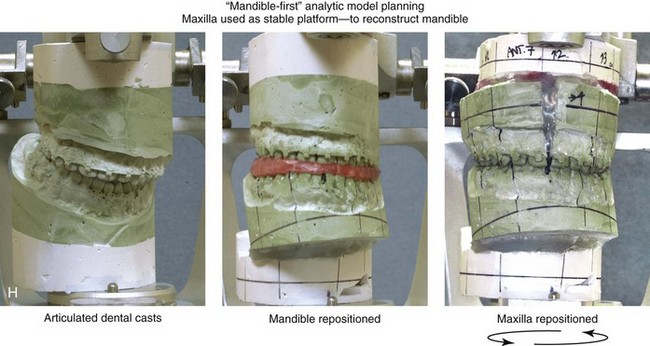

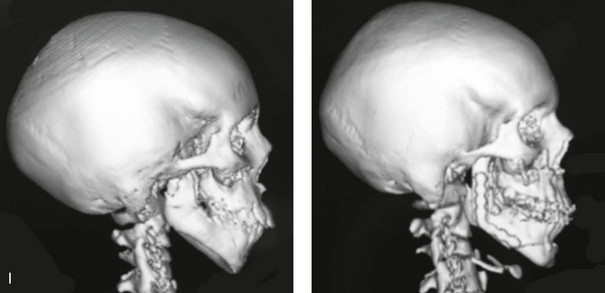

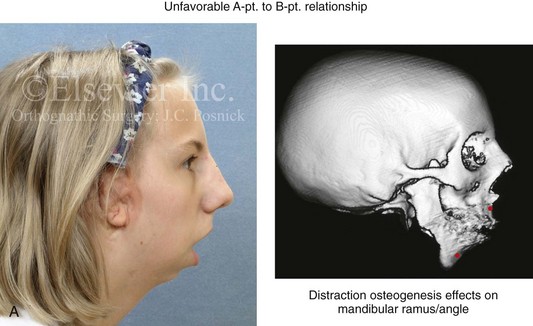

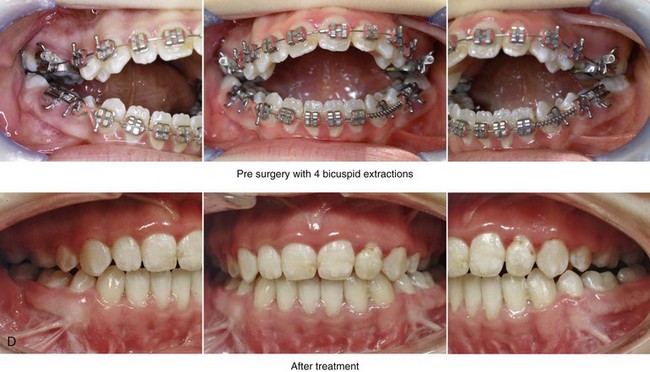

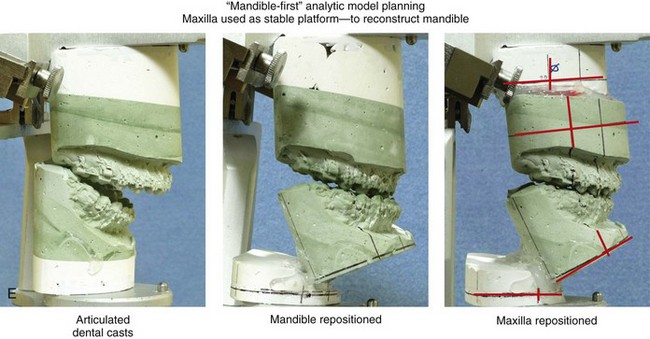

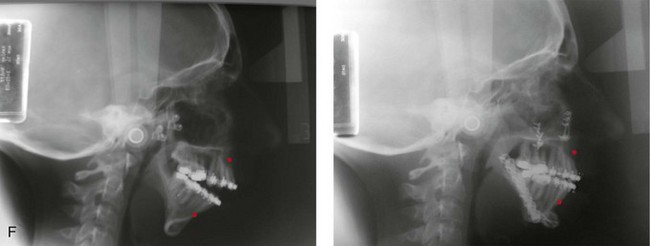

Figure 14-1 There are specific clinical settings in which obtaining an accurate and reliable centric relation (CR) can be problematic. Examples include individuals with atrophy of a condylar head (e.g., after a displaced condyle fracture) or those with specific syndromes in which aplasia of the glenoid fossa and condyle of the ascending ramus is extensive (e.g., Treacher Collins syndrome, hemifacial microsomia [HFM] with Kaban type IIB or III mandibular malformations). In addition, there are unique circumstances in which patients undergo bimaxillary procedures that require posterior maxillary lengthening to the extent that clockwise rotation of the mandible would result in a translational movement of the condyles in the glenoid fossa. In these cases, a mandible-first approach to analytic model planning is indicated. Several clinical examples are shown. A, A 16-year-old boy who had sustained a fracture of the right condyle of the mandible earlier during his childhood presented as a teenager with facial asymmetry. Complete atrophy of the right condyle had occurred, with a loss of posterior facial height. For this reason, a stable CR bite registration was not possible. Facial and computed tomography (CT) scan views are shown to confirm these facts. B, A 14-year-old girl with right-sided HFM and a Kaban type IIB condyle and ascending ramus malformation is shown. Because of these conditions, obtaining a consistent CR bite registration was not possible. Facial and CT scan views confirm these findings. C, An 11 year-old-boy who was born with right-sided HFM and a Kaban type IIB condyle and ascending ramus malformation is shown. Because of these conditions, obtaining a consistent CR bite registration was not possible. Facial and CT scan views confirm these findings. D, A teenage girl with a bilateral form of HFM and a Kaban type IIA condyle and ascending ramus malformation is shown. Although a stable CR bite registration could be obtained, the correction of the bimaxillary deformity requires significant counterclockwise rotation of the maxilla, including the lengthening of the posterior facial height of the maxilla. The use of standard maxilla-first analytic model planning would require clockwise rotation of the mandible to place the intermediate splint to the extent that translational movement of the condyles in the glenoid fossa would occur. For this reason, a mandible-first approach is required. Facial and CT scan views confirm these findings.

Controversies Surrounding Centric Relation

Definition of Centric Relation

The definition of CR remains somewhat controversial, and it is frequently misstated.46–49 In 1987, the definition of CR underwent a change in terminology from being considered a mandibular position in which the condyles are seated in the most “posterior superior” position to one in which the condyles are placed in the most “superior anterior” position in the glenoid fossa.45,46 For analytic model planning in preparation for orthognathic surgery, defining the exact position of each condylar head during mandibular protrusion and lateral excursions is not critical. However, it is essential to locate a mandibular position that is reproducible with the teeth in occlusion. This must be obtained without the assistance of the patient (i.e., with fully relaxed masticatory muscles), and it needs to be reliably accomplished both preoperatively and intraoperatively. This position must also be transferable to the articulator in the laboratory for model planning to be accomplished accurately. An erroneous and inconsistent recording of CR will lead to the malpositioning of the maxilla or mandible during surgery.

A survey study conducted by Truitt and colleagues confirmed that 98% of oral and maxillofacial surgeons define CR as the most posterior superior seating of the condyle in the fossa.51 Interestingly, a majority of the orthodontists surveyed agree with the surgeons’ definition of CR, but there was less consistency.22,41 According to the survey, surgeons and orthodontists do agree that, in preparation for orthognathic surgery, analytic model planning requires that casts of the teeth be mounted in CR on a semi-adjustable articulator.

Capturing Centric Relation

Hellsing and McWilliam used a subtraction technique to assess the repeatability of CR that is recorded with a one-handed push-back technique.21 They found that, with the use of this technique, the mandibular condyles can be seated in a reproducible position and thus be well suited for the registration of CR. Campos and colleagues compared the swallowing technique with the chin-point guidance technique when the patient was in both upright and supine body positions.3,5,9,15,21 Both techniques were found to establish physiologic CR in a reproducible manner. Interestingly, when the chin-point guidance method was used, the work of these authors suggested that reliability was greater with the patient in the upright, seated position as compared with the supine position.

Simon and Nicholls compared the chin-point guidance, chin-point guidance with ramus support, and bimanual manipulation techniques.43 They found that there were no significant differences in the range of mandibular positions that were observed. Interestingly, their study patients did not include individuals with jaw deformities. It is known that patients with specific patterns of jaw deformity (e.g., Class II retrognathism) are more likely to involuntarily posture the mandible forward during the swallowing technique.

Unstable (Unreliable) Centric Relation

Alternative methods to the standard analytic model planning approach to bimaxillary orthognathic surgery have been described in an attempt to improve the accuracy and predictability of outcomes.8,11,34,37,50,52 Recently, surgeons have also begun looking to computer-aided design and computer-aided modeling software to assist with the planning and implementation of orthognathic procedures (see Chapter 13).3,4,7,14,16,18,19,20,29,30,31,38,42,44,54,55,56

The subset of patients in which obtaining an accurate CR is not feasible are well suited for a “mandible-first” approach. Common clinical examples of these patients include the following: 1) those with specific congenital anomalies (e.g., hemifacial microsomia with Kaban Type IIB or III malformations) (Fig. 14-2 and 14-3) 2) those with specific types of trauma (e.g., after condylar fracture with resorption or after ankylosis release with condylar resection) 3) those with specific pathology (e.g., after condylar resection for tumor) and 4) those with the inability to cooperate in the office setting (e.g., those with neuropsychiatric disorders that involve uncontrolled masticatory muscle spasticity).

A mandible-first approach to analytic model planning is also indicated in unique clinical circumstances in which significant posterior maxillary lengthening is planned to the extent that the clockwise rotation of the mandible will require the translational movement of the condyles in the glenoid fossa during the use of the intermediate splint (Fig. 14-4). Fortunately, these cases are not common; very few patients require the actual lengthening of the posterior maxillary height. Furthermore, those who do generally either require the closure of baseline posterior open bites (i.e., cases that involve the failure of the posterior dentition to erupt) or are undergoing simultanous advancement. For example, the advantage of the counterclockwise rotation of the maxillary and mandibular planes (i.e., pitch orientation) is frequently seen in the clinical setting of a long face growth pattern. This counter clockwise rotation is generally accomplished via the differential intrusion of the maxilla (i.e., anterior more so than posterior). This does not require the lengthening of the posterior maxillary height or the overall posterior facial height (see Chapter 21).

Mandible-First Analytic Model Planning Technique

We prefer to use the mandible-first analytic model planning technique, in only specific clinical situations (see Fig. 14-1 through 14-4).8,11,34,37,39,52 However, whichever method of model planning is used, all orthognathic patients require a thorough clinical history and physical examination. A maxillofacial and focused dental assessment is also completed with particular emphasis on the accurate documentation of the following: 1) any maxillary occlusal cant (i.e., role orientation) 2) the maxillary and mandibular dental midline positions relative to the facial midline (i.e., yaw orientation) 3) any disproportions in vertical facial height 4) any disproportions in the horizontal projection of each jaw and 5) any advantage to the alteration of the maxillary or mandibular planes (i.e., pitch orientation); (see Chapter 12).

The basic technical aspects of mandible-first analytic model planning include the following:

1. To register the bite in a patient with a unilateral “free-floating” condyle–glenoid fossa relationship (e.g., Kaban type IIB or III hemifacial microsomia, the absence of the condyle after tumor resection or trauma), the mandible is manipulated with the “normal” condyle placed reliably in the terminal hinge position and with the “abnormal” (i.e., contralateral) condyle seated in its most posterior-superior position. This will demonstrate the maximum mandibular deformity. A wax bite registration is taken in this position.

2. A face-bow registration is obtained. Care is taken to accurately reproduce the patient’s existing maxillary plane (pitch orientation), cant (role orientation), and midline (yaw orientation) in relationship to the upper face. If the cranial base and the external auditory canals have essentially normal morphology, this is accomplished in a traditional fashion with the use of the standard face-bow technique, which involves placing an earpiece in each ear canal. If the patient’s ear canals are abnormally formed or positioned (e.g., in a patient with hemifacial microsomia with external auditory canal atresia), adjustments are made by using references to the parallelism of the floor and the morphology of the orbits. When doing so, the earpieces maybe placed against the patient’s cheek skin (rather than in the dysmorphic or absent external auditory canal). The patient’s head and neck are positioned by the operator in the natural head position for the face-bow registration (see Chapters 12 and 13).

3. Two maxillary and one mandibular alginate impressions are taken. The three dental impressions are poured in green die stone. The first maxillary cast is mounted onto the articulator in the standard fashion with white plaster and the use of the face-bow registration for orientation. The wax bite registration is then used to articulate the maxillary and mandibular casts to each other. The mandibular cast is then mounted on the articulator in the standard fashion, also with the use of white plaster (see Chapter 13).

4. The first maxillary mounting is removed, and the second maxillary cast is mounted. This is accomplished with the use of the original bite registration against the already mounted mandibular cast. Vertical and horizontal reference lines are created on each maxillary and mandibular unit (see Chapter 13). The Erickson Model Table is used to make baseline millimeter reference measurements on both maxillary units and the mandibular unit (see Chapter 13).

5. The original maxillary cast is then separated from its plaster base and three-dimensionally repositioned and reoriented according to the treatment plan. The Erickson Model Table is used to confirm the correct reorientation. If segmentation is required, it is completed before the reorientation of the maxilla to the plaster base (see Chapter 13). The reorientation of the maxilla takes into account the preferred horizontal, vertical, transverse (segmental) midline (yaw), cant (roll), and plane (pitch), needs (see Chapter 12). The maxillary cast is then secured to the plaster base with hot glue in the planned treatment position on the articulator (see Chapter 13).

6. The mandibular cast is then separated from its base and repositioned into the preferred final occlusion to the reoriented maxillary unit with the use of hot glue. The mandibular cast is remounted to its plaster base in the new position on the articulator with hot glue. The occlusion is released (i.e., the glue that secured the occlusion is removed), and a “maxillary-positioning” splint is fabricated with acrylic (see Chapter 13).

7. Next, the repositioned (reoriented) maxillary unit is removed from the articulator and replaced with the “uncut” second maxillary unit. This indicates the new mandibular location and the “unoperated” maxillary position. The “mandibular-positioning” splint is then fabricated with acrylic.

Technical Aspects of Executing the Mandible-First Approach During Orthognathic Surgery

Consider as an example an individual with hemifacial microsomia and a Kaban type IIB mandibular malformation ((Fig. 14-2 and 14-3). When using the mandible-first approach, the “normal” side of the ramus of the mandible is split sagittally in the usual way (i.e. sagittal ramus osteotomy of mandible). The distal mandible is then placed into its treatment-planned final position with the use of the prefabricated “mandibular-positioning” splint, and intermaxillary fixation (IMF) is established. To fully mobilize the distal mandible and secure it into the new occlusion, it may be necessary to 1) complete an ipsilateral coronoidectomy, 2) excise portions of the rudimentary (ipsilateral) mandible, or 3) both.

After the distal mandible is in the splint and secured with IMF, the proximal segment on the “normal” side is seated into the terminal hinge position. Rigid internal fixation (e.g., bicortical screws) is then established across the ramus osteotomy site (see Chapter 15).

The “mandibular-positioning” splint is removed, and the maxillary (Le Fort I) osteotomy is performed. After down-fracture and disimpaction (including segmentation, if indicated), the “maxillary-positioning” splint is used to achieve the treatment-planned maxillary reorientation. Plate and screw fixation is secured across the maxillary osteotomy sites in the usual manor (see Chapter 15). The IMF is released, and an accurate and reproducible occlusion is confirmed. The splint is either removed or left in place, depending on the patient’s clinical healing needs.

Mandible-First Analytic Model Planning: Step-by-Step Approach

1. Obtain a wax bite registration with the normal (unaffected) condyle seated in the terminal hinge position and with the abnormal (hypoplastic) condyle positioned as posterior and superiorly against the skull base as possible.

2. Use the face-bow device to register the relationships of the maxilla, glenoid fossa, and the skull base while the patient is in the natural head position (NHP). Use a modified technique if ear canals and the orbital symmetry are abnormal.

3. Take alginate impressions (two maxillary, one mandibular).

4. Pour alginate impressions in green die stone with a 25- to 30-mm base.

5. Mount the first maxillary cast onto the articulator base plate with the use of white plaster and the face-bow recording.

6. Turn the articulator upside down and place the mandibular cast onto the already mounted maxillary unit with the use of the wax bite registration. Mount the mandible cast onto the articulator base plate with white plaster.

7. Remove the mounted maxillary unit, and mount the second maxillary cast onto the articulator base plate with white plaster and the use of the same CR bite registration.

8. Mark vertical and horizontal reference lines on all three units, and take baseline measurements on the first maxillary unit with the use of the Erickson Model Table.

9. Perform model surgery on the first maxillary cast (including segmentation, if indicated). Place the maxilla in its treatment-planned location. Use the Erickson Model Table to confirm correct positioning. Secure the maxillary cast to the articulator (in its new location) with hot glue.

10. Separate the mandibular cast from the base. Secure the mandibular cast with hot glue into the optimal final occlusion against the repositioned maxillary cast. Secure the mandibular cast with hot glue or plaster back onto the base plate of the articulator.

11. Release the occlusion (i.e., remove the glue), and fabricate the “maxillary-positioning” splint in the standard fashion with the use of acrylic.

12. Remove the first maxillary (cut) unit, which is currently on the articulator, and place the second (uncut) maxillary unit.

13. Fabricate the “mandibular-positioning” splint in the standard fashion with the use of acrylic. This will be with the final (cut) mandibular unit and initial (uncut) maxillary unit.

References

1. 2000 Series Articulator, Whip Mix Corporation, 1 Farmington Ave, PO Box 17183, Louisville, KY 40217.

2. Adrien, P, Schouver, J. Methods for minimizing the errors in mandibular model mounting on an articulator. J Oral Rehabil. 1997; 24:929.

3. Amira software. TGS, Houston, Texas, 2010. http://www. tgs. com

4. Assael, LA. Editorial. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67:2041.

5. Becker, CM, Kaiser, DA, Schwalm, C. Mandibular centricity: centric relation. J Prosthet Dent. 2000; 83:158.

6. Bell, W, Proffit, W, White, R. Surgical correction of dentofacial deformities, ed 6. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Company; 1980.

7. Bell, RB. Computer planning and intraoperative navigation in orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:592–605.

8. Buckley, MJ, Tucker, MR, Fredette, SA. An alternative approach for staging simultaneous maxillary and mandibular osteotomies. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1987; 2:75.

9. Campos, AA, Nathanson, D, Rose, L. Reproducibility and condylar position of a physiologic maxillomandibular centric relation in upright and supine body position. J Prosthet Dent. 1996; 76:282.

10. Chow, TW, Clark, RKF, Cooke, MS. Errors in mounting maxillary casts using face-bow records as a result of an anatomical variation. J Dent Res. 1985; 13:277–282.

11. Cottrell, DA, Wolford, LM. Altered orthognathic surgical sequencing and a modified approach to model surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994; 52:1010.

12. Ellis, E, III. Accuracy of model surgery: evaluation of an old technique and introduction of a new one. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1990; 48:1161.

13. Ellis, E, III., Tharanon, W, Gambrell, K. Accuracy of face-bow transfer: effect on surgical prediction and postsurgical result. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1992; 30:362.

14. Ellis, E, III. Bimaxillary surgery using an intermediate splint to position the maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999; 57:53–56.

15. Erickson Model Table, Great Lakes Orthodontics, Ltd, 199 Fire Tower Drive, Tonawanda, NY 14151–15111.

16. Gateno, J, Xia, J, Teichgraeber, J, et al. The precision of computer-generated surgical splint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61:814.

17. Gateno, J, Teichgraeber, JF, Xia, JJ. Three-dimensional surgical planning for maxillary and midface distraction osteogenesis. J Craniofac Surg. 2003; 14:833–839.

18. Gateno, J, Xia, JJ, Teichgraeber, JF, et al. Clinical feasibility of computer-aided surgical simulation (CASS) in the treatment of complex cranio-maxillofacial deformities. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65(4):728–734.

19. Gateno, J, Xia, JJ, Teichgraeber, JF. New 3-dimensional cephalometric analysis for orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:606–622.

20. Gateno, J, Xia, JJ, Teichgraeber, JF. Effect of facial asymmetry on 2-dimensional and 3-dimensional cephalometric measurements. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:655–662.

21. Hellsing, G, McWilliam, JS. Repeatability of the mandibular retruded position. J Oral Rehabil. 1985; 12:1.

22. Jasinevicius, TR, Yellowitz, JA, Vaughan, GG, et al. Centric relation definitions taught in 7 dental schools: results of faculty and student surveys. J Prosthodont. 2000; 9:87.

23. Keshvad, A, Winstanley, RB. An appraisal of the literature on centric relation: part I. J Oral Rehabil. 2000; 27:823.

24. Keshvad, A, Winstanley, RB. An appraisal of the literature on centric relation: part II. J Oral Rehabil. 2000; 27:1013.

25. Keshvad, A, Winstanley, RB. An appraisal of the literature on centric relation: part III. J Oral Rehabil. 2001; 28:55.

26. Landes, C, Sterz, M. Proximal segment positioning in bilateral sagittal split osteotomy: Intraoperative controlled positioning by a positioning splint. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003; 61:1423.

27. Landes, C. Proximal segment positioning in bilateral sagittal split osteotomy: intraoperative dynamic positioning and monitoring by sonography. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2004; 62:22.

28. Lapp, TH. Bimaxillary surgery without the use of an intermediate splint to position the maxilla. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999; 57:57–60.

29. Lubbers, HT, Jacobsen, C, Matthews, F, et al. Surgical navigation in craniomaxillofacial surgery: expensive toy or useful tool? A classification of different indications. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:300–308.

30. Maxilim software. Medicim Medical Image Computing, Mechelen, Belgium, 2010. http://www. medicim. be

31. McCormick, SU, Drew, SJ. Virtual model surgery for efficient planning and surgical performance. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:638–644.

32. Nattestad, A, Vedtofte, P, Mosekilde, E. The significance of an erroneous recording of the center of mandibular rotation in orthognathic surgery. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1991; 19:254.

33. O’Malley, AM, Milosevic, A. Comparison of three face bow/semi-adjustable articulator systems for planning orthognathic surgery. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2000; 38:185.

34. Perez, D, Ellis, E, III. Sequencing bimaxillary surgery: mandible first. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:2217–2224.

35. Politi, M, Toro, C, Costa, F, et al. Intraoperative awakening of the patient during orthognathic surgery: a method to prevent the condylar sag. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007; 65:109.

36. Posnick, JC, Fantuzzo, JJ, Orchin, J. Deliberate operative rotation of the maxillo-mandibular complex to alter the A-point to B-point relationship for enhanced facial esthetics. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:1687–1695.

37. Posnick, JC, Ricalde, P, Pong, NG. A modified approach to “model planning” in orthognathic surgery for patients without a reliable centric relation. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006; 64:347–356.

38. Quevedo, LA, Ruiz, JV, Quevedo, CA. Using a clinical protocol for orthognathic surgery and assessing a 3-dimensional virtual approach: current therapy. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:623–637.

39. Quick Mount Face-Bow, Whip Mix Corporation, 361 Farmington Ave, PO Box 17183, Louisville, KY 40217.

40. Rinchuse, DJ, Kandasamy, S. Articulators in orthodontics: an evidence-based perspective. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006; 129:299–308.

41. Rinchuse, DJ, Kandasamy, S. Centric relation: a historical and contemporary orthodontic perspective. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006; 137:494–501.

42. Schendel, S, Jacobsen, R. Three-dimensional imaging and computer simulation for office-based surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67:2107.

43. Simon, RL, Nicholls, JI. Variability of passively recorded centric relation. J Prosthet Dent. 1980; 44:21.

44. Swennen, RJ, Mollemans, W, Schutyser, F. Three-dimensional treatment planning of orthognathic surgery in the era of virtual imaging. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67:2080.

45. Tarantola, GJ, Becker, IM, Gremillion, H. The reproducibility of centric relation: a clinical approach. J Am Dent Assoc. 1997; 128:1245.

46. The glossary of prosthodontic terms. J Prosthet Dent. 1987; 58:713.

47. The glossary of prosthodontic terms. J Prosthet Dent. 1994; 71:40.

48. The glossary of prosthodontic terms. J Prosthet Dent. 1999; 81:39.

49. The glossary of prosthodontic terms. J Prosthet Dent. 2005; 94:10.

50. Thomas, PM. Altered orthognathic surgical sequencing and a modified approach to model surgery [discussion]. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994; 52:1020–1021.

51. Truitt, J, Strauss, RA, Best, A. Centric relation: a survey study to determine whether a consensus exists between oral and maxillofacial surgeons and orthodontists. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67:1058–1061.

52. Turvey, T. Sequencing of two-jaw surgery: the case for operating on the maxilla first. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:2225.

53. Van Sickels, JE, Larsen, AJ, Triplett, RG. Predictability of maxillary surgery: a comparison of internal and external reference marks. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1986; 61:542.

54. Xia, J, Gateno, J, Teichgraeber, J. New clinical protocol to evaluate craniomaxillofacial deformity and plan surgical correction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009; 67:2093.

55. Xia, JJ, McGrory, JK, Gateno, J, et al. A new method to orient 3-dimensional computed tomography models to the natural head position: a clinical feasibility study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:584–591.

56. Xia, JJ, Shevchenko, L, Gateno, J, et al. Outcome study of computer-aided surgical simulation in the treatment of patients with craniomaxillofacial deformities. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011; 69:2014–2024.