Chapter 16 Managing the Open Abdomen

1 Clinical Anatomy

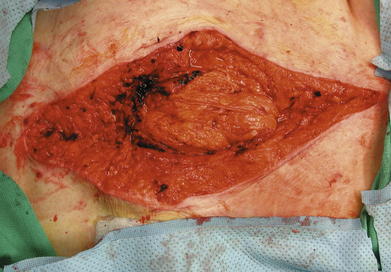

Management of the open abdomen does not depend so much on recognition of the anatomy of the abdominal wall but on the maintenance of the anterior peritoneal space (Fig. 16-1). If this space is maintained, there is the potential to continue to work toward closure of the abdominal wall. If this space is lost, then the surgeon must move on to protecting the viscera from the external environment and trying to obtain skin closure over the bowel.

2 Preoperative Considerations

1 Resuscitation

Patients who require open abdomens usually fall into one of two categories: those who still have an acute process ongoing (Fig. 16-2) and those who are in the stable phase and are in the process of having their abdomens closed (Fig. 16-3).

Those in the acute phase need to have physiologic abnormalities—acidosis, hypothermia, and coagulopathy—corrected. Providing crystalloid and blood products will accomplish this, although volume resuscitation can itself have adverse effects, specifically on intraabdominal pressure and the development of abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). Even if the abdomen has a temporary covering in place, intraabdominal pressures need to be monitored. This is typically done with monitoring of bladder pressure. If bladder pressure is elevated or if the patient is clinically developing ACS, then the closure that was placed on the abdomen needs to be loosened to allow the viscera to expand and take pressure off of the vena cava, kidneys, and lungs.

2 Pharmacologic Management

Nutrition also can be considered a pharmacologic intervention. There is no contraindication to enteral nutrition just because the abdomen is open. Although there may be other reasons not to institute enteral feedings, the presence of an open abdomen is not one of them.

3 Operative Steps

1 Decision to Leave the Abdomen Open

The decision to leave an abdomen open depends on the clinical scenario, as previously stated. It does not matter if the patient’s condition is acute or chronic; anatomy and physiology are what drive the decision. Once the decision is made, the steps are similar no matter the reason.

2 Technique

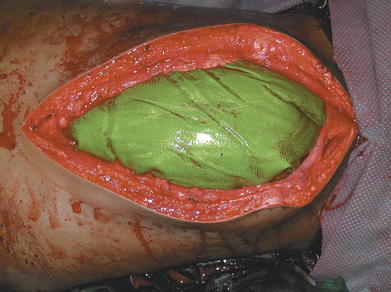

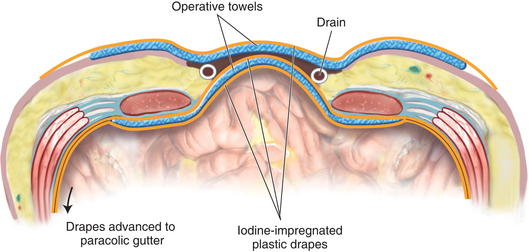

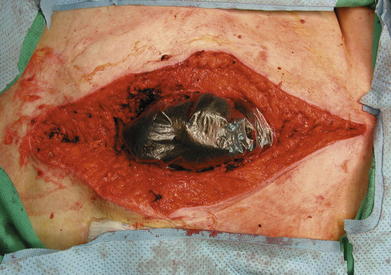

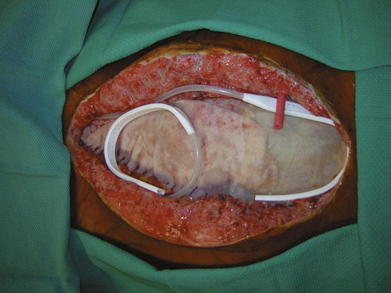

All visceral surgery should be completed, if possible. Once this is done, a temporary coverage for the intestine is fashioned. This can be a plastic drape, iodine-impregnated drape (Figs. 16-4 to 16-9), or a commercially available visceral drape (Figs. 16-10 to 16-13). The key point is to get the drape under the abdominal wall and passed all the way laterally to the paracolic gutters. The author believes that some sort of support of the visceral drape is needed to accomplish this. The Barker technique, in which an operative towel is sandwiched between two iodine-impregnated drapes, is favored. This provides enough support such that the covering will not shift once placed.

A blue operative towel is placed over the drains and is then covered by another sheet of iodine-impregnated plastic. Before placing this final sheet of plastic, the drains are connected to wall suction and maintained on wall suction until just before transfer out of the operating room.

3 Fascial Closure

While none of these patients are candidates for complete fascial closure, most patients can have part of their abdominal wall reapproximated at each operation (Figs. 16-14 to 16-16). Every time a patient goes to the operating room, an attempt should be made to bring at least some of the fascia back together. This may be just one or two stitches, but in the end, it is progress, and progress is what is needed in these difficult patients.

4 Postoperative Care

2 Reoperation

Patients should be taken to surgery whenever it is felt that more progress can be made with regards to their closure. Usually this means every day or every other day. At the time of these procedures, every attempt should be made to reapproximate some fascia.

5 Pitfalls/Pearls

A time will come when the patient is not getting any better, and the reason for this is the open abdomen. This patient has developed tertiary peritonitis, and the only way they are going to get better is to cover the viscera. In this patient, a biologic-type mesh is believed to be the most appropriate closure. It prevents adhesions (good for reoperation at a later date); protects the viscera during dressing changes (lower fistula rate); and in select patients, may function as their definitive closure.

Brock W.B., Barker D.E., Burns R.P. Temporary closure of open abdominal wounds: The vacuum pack. Am Surg. 1995;61:30-35.

Diaz J.J., Cullinane D.C., Dutton W.D., et al. The management of the open abdomen in trauma and emergency general surgery: Part 1- Damage Control. J Trauma. 2010;68(6):1425-1438.

Vargo D., Richardson J.D., editors. “Management of the Open Abdomen: From Initial Operation to Definitive Closure,”. Am Surg, Vol. 75. 2009, S1-S22. (2)