15 Managing symptoms

assess, plan, implement and evaluate

Introduction

In any clinical setting you will have the potential to care for a person with a cancer diagnosis who is experiencing one or more of the distressing symptoms explored in this chapter. By engaging in the exercises for each symptom, you are given the opportunity to consider how the symptom can be managed in any specific placement. It is important to apply the principles of assessment and holistic care of a patient introduced below. Patient care must also take into consideration the cultural and ethnic needs of patients and family members. These are explored in more detail in the Chapter 16, however it is important to start to consider the implications as you develop cultural competence in symptom management. This chapter explores some of the principles in supporting a patient with a cancer diagnosis who is experiencing one or more distressing symptom. This can happen during treatment for the cancer, as well as if the patient is in the palliative care stage of the illness. Some symptoms can continue after the patient has completely recovered from the cancer. For example, fatigue or taste changes can sometimes occur following chemotherapy or radiotherapy and may last for many years. Sometimes symptoms can occur as ‘acute events’ and need to be dealt with swiftly. These include hypercalcaemia and spinal cord compression.

The principles of assessment

The nursing process (Roper et al 2000) suggests assessment is the ‘first step’ in the four-step cycle of planning, implementing and evaluating care. Uys and Habermann (2005) recognise the importance of collecting information in the assessment process, while Holland et al (2008) refer to assessment as a ‘cyclical activity’ that includes collecting and reviewing information and linking this assessment to impact on activities of living.

Remember, the information we gather includes that from the patient, family and professional teams.

The principles of planning care

When we have gathered information about a patient, we are then able to plan the care we are going to provide. It is important that any information is clarified and communicated with wider team members in an appropriate way. Remember that any information we have about a patient is confidential and must be respected and kept safe at all times. The NMC code of conduct (NMC 2008) states confidentiality as a patient’s right so, as you gather information, it is important to inform patients how this will be used. Doing this shows the patient respect.

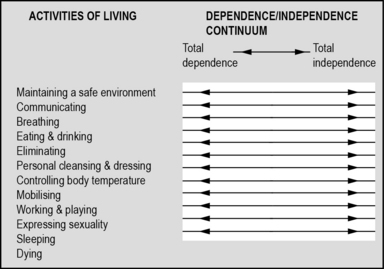

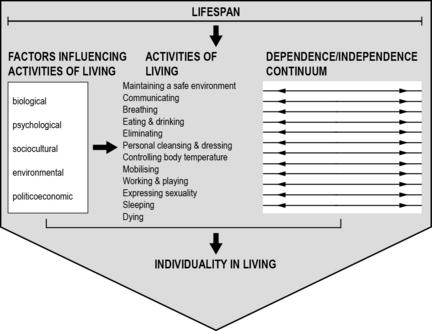

One way to collate this information in a logical and holistic way is by using the Roper, Logan and Tierney model (Roper et al 2000) (Figs 15.1 and 15.2). This model was originally developed in 1980 by Nancy Roper and published under the title The Elements of Nursing and is a collection of core themes around activities of living. They were developed with the idea that activities of living can be applied to patients in any clinical area, are patient focused and can give a clear idea of the needs of a patient and their family at any point in time. You may have already seen this model used in a previous practice placement. Sometimes they are referred to as the activities of daily living (ADLs). Admission assessment forms for both acute hospitals and community settings are often based on this model.

There are 12 activities of living which take a holistic approach:

1. Maintaining a safe environment.

6. Personal cleansing and dressing.

These activities of living are not separate themes but are linked through biological, psychosocial and political factors. Each of the activities are interlinked and will impact on a person’s degree of dependence or independence (Holland et al 2008).

Gathering information about a patient and their family is not easy. There are many things that can hinder the effective collection of data and this can have a direct impact on the care given or understanding of what the priority needs are for a patient and their family. Information can be gathered about a patient at admission (part 1). If the patient dies, part 2 can be completed about what happened at the time of death and how the family reacted. This information can help with planning ongoing bereavement support (See Appendix 2).

Read through the following scenario and consider the information you have about the patient:

You are helping to care for a man who has been admitted from another ward in the hospital and you have been invited to go with the staff nurse on the ward round.

You are helping to care for a man who has been admitted from another ward in the hospital and you have been invited to go with the staff nurse on the ward round.

In this morning’s evaluation of patient care, the following has been written by the night staff:

In this morning’s evaluation of patient care, the following has been written by the night staff:

The doctor says to the patient, ‘I hear you are not sleeping’. The patient answers ‘No Doctor’.

The doctor says to the patient, ‘I hear you are not sleeping’. The patient answers ‘No Doctor’.

On the ward round, the doctors discuss a prescription for sleeping tablets.

On the ward round, the doctors discuss a prescription for sleeping tablets.

On the activities of living admission sheet, the following is written:

On the activities of living admission sheet, the following is written:

You were on a late shift last night and overheard a conversation between this patient and the waitress who was serving the evening drinks:

You were on a late shift last night and overheard a conversation between this patient and the waitress who was serving the evening drinks:

Consider the information we have about this patient, his sleep pattern and his current needs.

Here is a list of what we already know about the patient:

1. He has a long-term sleep pattern that has not changed for several years.

2. He is open with this information with some members of the care team.

3. He appears reluctant to freely offer information to the doctor.

4. Having a cup of tea in the night seems to help him feel settled.

Where can other information be found?

1. Admission notes from his previous ward and possible previous admissions.

2. A conversation with the patient to ask what his sleep pattern means to him. Is it a problem? What helps?

The principles of managing common symptoms experienced by cancer and palliative care patients

• Communication: this includes the information gathering phase and involves how information about the patient is communicated with the patient as well as other members of the care team. Understanding what the key issues are, discussing treatment options and communicating options is the first stage in ensuring care planned considers all the important factors that are relevant to the patient.

• Choice: giving information to the patient about what is happening is essential for the patient to make an informed choice about treatment. This includes the concept of consent and is one of the underpinning ethical principles of autonomy. To refresh your knowledge of ethical principles, go back to Chapter 5. If patients feel they have choices in their treatment regimen, they are more likely be compliant with taking medication, attending appointments, etc. For example, if a patient understands the link between a specific medication and risk of constipation, they are more likely to take the prescribed laxatives.

• Care: this must be planned, holistic and patient centred. Attention to detail is vital. Care must be continually evaluated by all members of the multidisciplinary team, documented and then renegotiated with the patient and family. Always consider the needs of patients.

Under each of the ‘three C’ headings, list all the activities you can undertake as a nurse to ensure principles of symptom management are achieved. To help you do this, reflect back on the observations you have made in current and previous placements. To refresh your knowledge of the principles of assessment, go back to page 129.

Good symptom management relies on an effective assessment process.

Pain: causes, assessment and management

A universally accepted definition of pain is that it is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience that is associated with actual or potential tissue damage (International Association for the Study of Pain 2007). Pain is complex and understanding what is both initiating the pain and maintaining it is important for effective management. Chapter 5 on palliative care introduced you to the concept of ‘total pain’. The contemporary way of referring to total pain is from a ‘biopsychosocial’ perspective (Holdcroft & Power 2003) and can be divided into three factors:

1. The person – includes biological and psychological influences.

2. Type of disease – includes past history and present disease.

3. Environment – includes cultural expectations, upbringing, roles, lifestyle.

The most challenging part of managing pain is the subjectivity of pain; what it means to one person is different from another person, as is the individual’s ability to manage the pain. ‘Pain is whatever the person experiencing it says it is, existing whenever he says it does’ (McCaffery 1968:95). While this work of McCaffery is old, it continues to be a fundamental principle of pain management.

1. Transduction – involves the process of converting mechanical, thermal or chemical noxious or painful stimulus into a nervous impulse.

2. Transmission – involves the nervous impulse being conducted by sensory nerves to the central nervous system. Different nerves carry different impulses.

3. Perception – conscious perception of pain is perceived by an individual once all the incoming nervous messages are interpreted by the brain.

4. Modulation – throughout the process, various physiological and psychological mechanisms can adjust the nociceptive message to either increase or decrease the pain experienced.

Re-read the notes you made about your personal experiences of pain on page 39. Now consider how you might know a patient is in pain. Make a list of the words that a person might use to describe pain followed by a list of the behaviours you might observe. Consider how this information might have been gathered and be documented in the patient’s case notes and communicated across the care team.

Types of pain

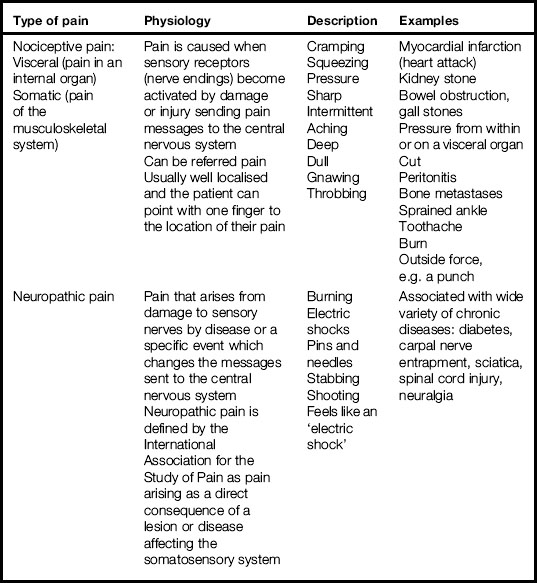

Table 15.1 gives a simple overview of two types of pain, the basic physiology and words associated with how pain might be experienced.

Using Table 15.1, write a few sentences about the impact the different types of pain can have on the activities of living.

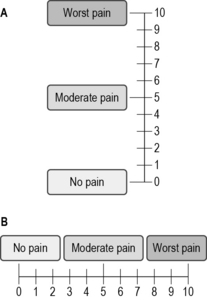

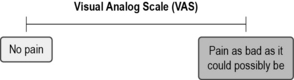

Assessing pain correctly is fundamental to ensuring analgesia prescribed is appropriate and effective. Asking how the pain is and getting the patient to describe the pain is a useful way to establish possible causes. Also finding out what makes it worse and what makes it better is important too. The assessment tool in Figure 15.3 is called the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) and is used in many clinical areas and is a quick way to explore pain with a patient.

Fig 15.3 Pain assessment tool

(reproduced with permission from McCaffery M, Pasero C (1999) Pain, clinical manual, 2nd edn. Mosby, St Louis)

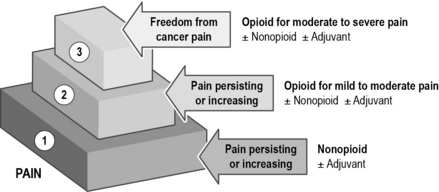

Management of pain

The World Health Organisation (WHO) analgesic step ladder is shown in Figure 15.4. Here we can see that analgesia is staged from a non-opioid, to a weak opioid and then to a strong opioid. This is the recommended ladder by which analgesia is prescribed.

Sometimes morphine analgesia is not prescribed or given ‘as required’ (prn) for fear it will harm the patient. Equally, this may be the reason a patient may refuse to take analgesia or admit to being in pain. An article which will help you to understand this issue in more depth is Stannard (2008) (see References).

Nausea and vomiting

The symptoms of nausea and vomiting are often associated together, bit this is not the right approach. It is important to consider the causes and management of nausea as separate to the causes and management of vomiting. Some patients will have both symptoms. Forty-two percent of patients with cancer have just nausea at some point while 32% have both nausea and vomiting together (Twycross et al 2009).

Nausea and vomiting can be caused by a wide range of factors, so understanding physiological processes is an important part of being able to gather the correct information in the assessment process. In the brain, there are specific areas that provoke the vomiting response: the vomiting centre and chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) in the medulla oblongata, which is at the base of the brain, the cerebral cortex and the vestibular centre. In addition, right through the gastrointestinal tract there are peripheral pathways where receptors send messages via the vagus nerve to the brain to activate the CTZ and vomiting centre. Figure 15.5 is a simple diagram demonstrating how the pathways work.

Fig 15.5 Vomiting pathways

(adapted from: Campbell T, Hately J (2000) The management of nausea and vomiting in advanced cancer. International Journal of Palliative Nursing 6(1):18–25)

1. Raised intracranial pressure: if intracranial pressure is raised, this will stimulate the vomiting centre which produces histamines. Effective management is to use antihistamines to reduce the histamines collecting in the vomiting centre.

2. Irritation of the visceral and gastrointestinal serosa, the lining of the gastrointestinal wall which secretes fluid to keep the bowel wall lubricated: once irritated, the peripheral nerves activate the vagus nerve to stimulate the vomiting centre.

3. Gastric stasis/gastric outlet obstruction: if the contents of the stomach or intestine become static or are obstructed, the peripheral nerves are stimulated to send messages via the vagus nerve to the vomiting centre. Stasis and obstruction can be caused by cancer or medication that slows down bowel movements, for example diamorphine.

4. Oesophageal obstruction: this can be caused directly by cancer, oral thrush or painful swallowing (odynophagia). As well as a stimulation of the vomiting centre by the peripheral nerves in the gastrointestinal tract, the flow of saliva can be increased. If this becomes a problem for the patient, medication can be prescribed to reduce saliva flow.

5. Pharyngeal stimulation: this can be caused by excessive sputum or oral thrush. Reducing histamines in the vomiting centre can relieve nausea.

6. Chemically-induced nausea: this can range from poisons to chemotherapy which stimulate the CTZ. Once stimulated, it will stimulate the vomiting centre.

7. Anxiety/anticipatory nausea/vomiting: this cause of vomiting is sometimes associated with anticipatory vomiting in patients who are waiting for a cycle of chemotherapy. Anxiety about the disease process, treatments, hospital admissions and psychosocial factors can all lead to nausea or/and vomiting. Giving the patient reassurance and medication to reduce anxiety can help to relieve nausea/vomiting.

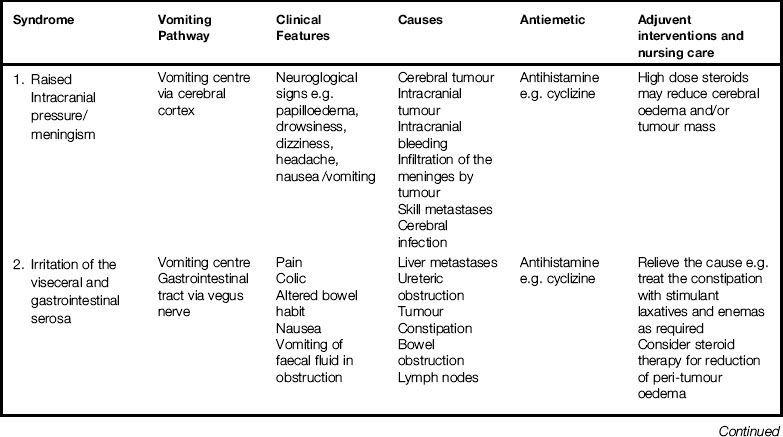

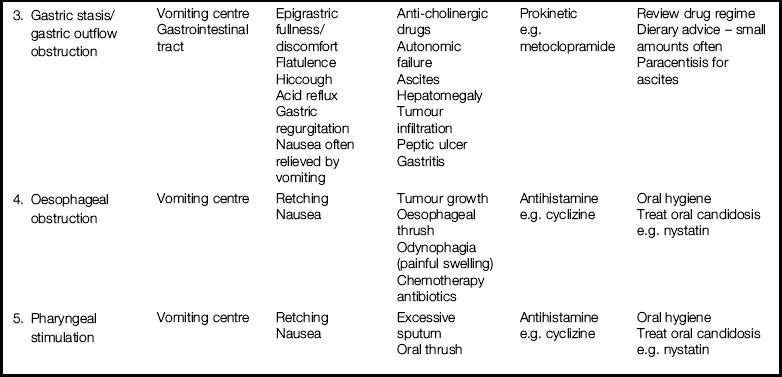

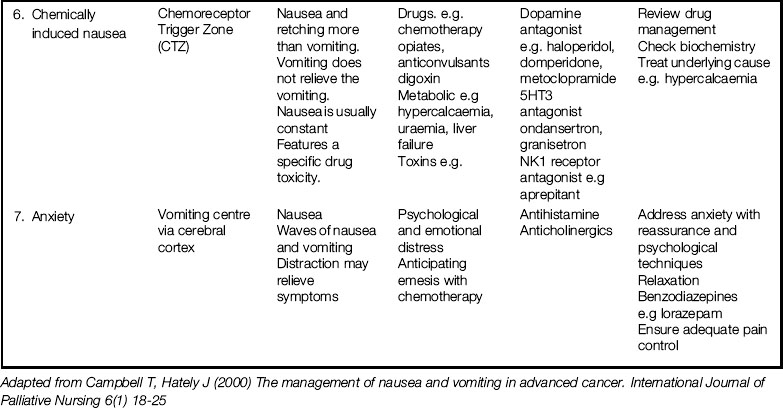

Understanding the physiology of vomiting pathways is the first step in assessment of nausea and/or vomiting. The specific treatment and care will depend on the cause(s). Table 15.2 links the vomiting pathways/syndromes to potential treatment options and nursing care and interventions.

Using the British National Formulary (BNF), find out a bit more about antiemetic drugs used for the different pathways. Look under ‘antiemetic’, ‘dopamine antagonist’ and ‘antihistamine and anxiolytic’. Jot down notes for each drug and link to the appropriate pathways using Table 15.2.

Remember that a patient who is vomiting can be given subcutaneous injections. Ideally these should be continued for 3 days of non-vomiting, then given orally (Twycross et al 2009).

Constipation

Half of the people diagnosed with cancer experience a change in their bowel habits leading to constipation (Twycross et al 2009). One in six of these will class this as severe and it is the most common reported gastrointestinal problem. Constipation is defined as the passage of hard, dry stools with excessive straining and decrease in frequency (Doyle et al 2005). How we define normal bowel movement is determined by the patient and their normal pattern. Taking a comprehensive history of bowel movements, and when changes have occurred in the past, can help with management.

Oral care

You might need to refresh your knowledge of mouth anatomy and physiology from your lecture notes to complete this exercise. If you have not had a lecture yet, consult a core anatomy and physiology textbook, either one that has been recommended by your training school or, alternatively, a textbook such as Clancy and McVicar (2009) (see References).

A clean healthy mouth is essential in reducing the risk of a patient developing thrush. This is an oral fungal infection called Candida albicans which is present in the mouth of about 50% of people. It becomes a problem if the chemistry of the oral cavity changes. Early assessment by taking a history and detecting new problems are important to establish how care can be prioritised and planned (Piper 2008). Many patients may have had poor mouth hygiene prior to their illness; for others, problems are new and distressing. Sorting out poor-fitting dentures early on can prevent a severely sore mouth developing as the disease progresses.

Fatigue

Cancer-related fatigue is the most common symptom experienced by patients receiving cancer treatments (Ahlberg et al 2003) and is described as ‘a persistent, subjective sense of tiredness related to cancer or cancer treatment that interferes with usual functioning’ (Mock et al 2005:1). The incidence of cancer-related fatigue is high – 82% of people with a cancer diagnosis will experience fatigue for a few days per month (Stone et al 2000). So it is very likely you will nurse a person with fatigue in this practice placement.

Another definition of fatigue suggests it is a ‘subjective unpleasant symptom which incorporates total body feelings ranging from tiredness to exhaustion, creating an unrelenting overall condition which interferes with the individuals’ ability to function to their normal capacity’ (Ream & Richardson 1996:527). This definition gives a clearer idea of the impact fatigue may have on activities of living and a person’s capacity to maintain normality. It is one of the first definitions of fatigue and continues to be one of the core understandings on which contemporary care is planned and delivered.

There are many causes of fatigue and a patient can have just one or many interacting together. This is why fatigue can be such a complex problem to effectively manage. Fatigue during and following both chemotherapy and radiotherapy is very common. It can also occur due to the cancer growing, infections, pain, medication, co-morbidities and anxiety/depression. Often fatigue and depression are interlinked (O’Regan & Hegarty 2009) and management needs to focus on both aspects of care.

Body image and altered body image

How we view our own body is important since it is the way we tell ourselves how we look to others. This image of self is the mental picture we have of ourself but is not necessarily the way other people see us. A change in the mental picture of self can have a big impact on how we view what is happening. For example, a woman receiving chemotherapy may lose her hair and this can impact on how she views herself. It is important to be aware that anticipation of a change in body image can start at diagnosis, well before treatment begins (Frith et al 2007). A change in one’s perception of body image is called ‘altered body image’ and is a complex symptom to manage. Altered body image can be temporary or permanent, depending on the causes and the person’s ability to cope with the change (Salter 1997). Often, altered body image becomes a problem because the patient does not have the ability to cope with the changes or because of the behaviour of others towards them (Price 2000). This can include lack of support, help and information from healthcare professionals who often fail to acknowledge the importance of how patients view themselves.

To explore further the impact of weight loss associated with advancing cancer on body image, read the article by Hinsley and Hughes (2007) (see References).

Breathlessness

Breathlessness is the ‘subjective experience of breathing discomfort’ (Twycross et al 2009:145). The distress a patient feels is individual to that person and does not always correspond to how we might view their breathlessness. A lot of anxiety and fear is associated with both the onset of breathlessness or worry that it will get worse. Breathlessness can be caused by a primary lung cancer, lung metastasis, respiratory muscle weakness or fluid within the lung cavity. This is called a pleural effusion and you may see a patient regularly returning to hospital to have the fluid removed from the lung; a pleural aspiration. Recurring effusions can be a sign of advancing disease. Pain, fatigue and anxiety can exacerbate the feelings of breathlessness and have a great impact on a person’s ability to undertake their activities of living.

Psychological distress

In Chapter 5, we introduced the concept of psychological distress when exploring the definition of palliative care. Also, we have considered the wellbeing of patients when looking at the activities of living. It is important to remember that a patient can experience a wide range of distressing feelings and emotions at any stage of the cancer journey. Providing support at all stages of this journey is an important part of nursing care. Awareness of the potential for distress and being able to recognise the signs is an important part of providing holistic care. Distress is often linked to the term ‘suffering’ and you will often hear the two linked. The degree of suffering or distress is not directly linked to the diagnosis or specific symptoms but more to how a particular patient associates meaning to what is happening (Payne et al 2008).

As nurses, we cannot always prevent suffering or psychological distress. Recognising the links between the two is the first step in being able to effectively support both the patient and their relatives. It is important to allow patients to express their feelings of distress, so they can be supported to work through their feelings of suffering. They may then be able to develop strength or resilience to help them face what the cancer diagnosis and treatment options may bring. Involving family and friends is really important. Often they feel helpless and distressed themselves when they see a person they care for so ill and unhappy. Encouraging patients and relatives to express these feelings helps to develop the therapeutic relationships (Burzotta & Noble 2010) essential in providing holistic care.

The principles of good psychological care include listening to patients and giving priority to what is distressing them most. By showing an interest in their story, we can create a safe place for them to express thoughts and feelings. This may help to give patients some control back to make decisions, helping to reduce feelings of loss. This is also an important part of developing a therapeutic relationship. Being aware of the potential barriers to providing psychological care for a person who is distressed is important. Read the Burzotta and Noble (2010) article which explores barriers in more detail. Make some notes about how these barriers might be reduced from the perspective of your current clinical placement.

Spinal cord compression

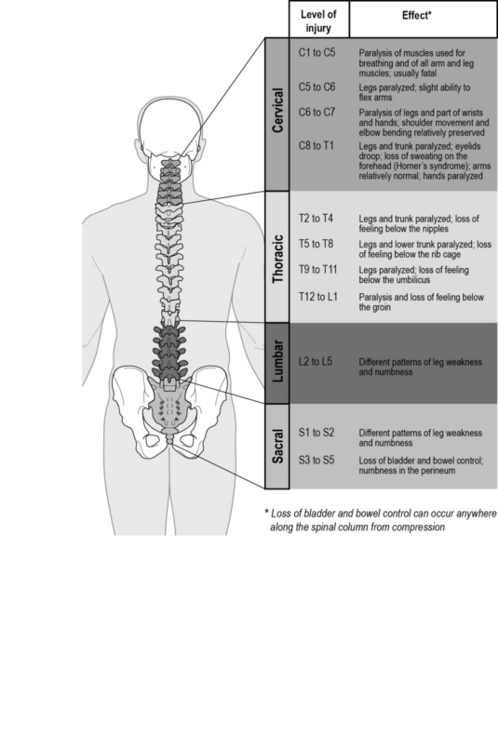

Abnormal pressure on the spinal cord is commonly referred to as spinal cord compression (SCC) and is seen predominantly in patients with advanced cancer. Compression can be caused directly or indirectly due to the spread of the cancer, often referred to as metastatic spinal cord compression (MSCC). Metastasis of the spinal column occurs in 3–5% of all patients with cancer (National Collaborating Centre for Cancer 2008). Figure 15.6 illustrates the MSCC of compression along the spinal cord.

Growth of the cancer can cause pressure or bleeding, affecting nerves around the spinal cord. It can also be caused or made worse by localised infection. Patients with MSCC may be receiving active chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatments. Alternatively, they may be in the palliative stage of their illness. For a more detailed explanation of the impact of a spinal cord compression, read the article by Drudge-Coates and Rajbabul (2008a).

Rapid assessment, diagnosis and management are vital for both groups of patients since the priority of care is to manage pain and prevent irreversible paralysis. Once paralysis has occurred, it usually cannot be reversed. Research shows that if a patient has the ability to walk at the time of diagnosis of MSCC, they are more likely to walk following treatment (Drudge-Coates & Rajbabul 2008b). Also, being mobile at the time of diagnosis indicates a better overall outcome following treatment (Levack et al 2001). Often immobility can start due to the onset of pain weeks or months before weakness occurs. MSCC is most common in patients diagnosed with breast, lung, prostate and thyroid cancer; in these patients, the incidence may be as high as 19% (National Collaborating Centre for Cancer 2008).

Table 15.3 compares prognosis for a number of spinal cord compression factors.

Table 15.3 Spinal cord compression factors (National Collaborating Centre for Cancer 2008:40)

| Good prognosis | Poor prognosis |

|---|---|

| Breast cancer as the primary site | Lung or melanoma primary |

| Solitary or few spinal metastases | Multiple spinal metastases |

| Absence of visceral metastases | Visceral metastases |

| Ability to walk aided or unaided | Unable to walk |

| Minimal neurological impairment | Severe weakness |

| No previous radiotherapy | Recurrence after radiotherapy |

The position of compression on the spine determines the symptoms patients experience (Fig. 15.7).

Accurate assessment is important in diagnosing MSCC. Low back pain is commonly the first symptom, occurring in 95% of patients, with weakness of limbs occurring in 85% of patients (Levack et al 2001). Changes in sensation are common and include numbness of the fingers and toes. It is also important to remember that a diagnosis if MSCC can be the first time a patient is aware that he/she has a diagnosis of cancer – 23% of patients diagnosed with MSCC have no prior cancer diagnosis (National Collaborating Centre for Cancer 2008).

Chapter 3 of the Metastatic Spinal Cord Compression Full Guidance document developed for NICE (National Collaborating Centre for Cancer 2008) explores the patient experience.

On the 4th day he had surgery to stabilise the spine but sadly this was all done far too late as the damage was done and he was left with no use of his legs, trunk or right arm (National Collaborating Centre for Cancer 2008:16).

In particular, consider the impacts the following may have on both the patient and family:

Hypercalcaemia

An increase in the normal amount of calcium in the blood is called hypercalcaemia. This is caused by cancer cells stimulating the release of calcium into the blood and involves osteoclast activity, bone resorption and the parathyroid gland. Normal blood calcium is between 2.2 mmol and 2.6 mmol. In a patient who has symptoms of hypercalcaemia, the blood calcium can be raised to over 3.5 mmol, and 3.75 mmol is an emergency situation which may lead to unconsciousness. For a patient with a cancer diagnosis, raised blood calcium is a sign of advancing disease and occurs in 10–20% of patients (Stewart 2005). Hypercalcaemia occurs more commonly in cancers of the breast, myeloma, lung, stomach, small intestine and prostate.

Symptoms are associated with the rate of increase of calcium in the blood, rather than the actual amount of calcium. Commonly a patient will experience nausea or/and vomiting, abdominal pain, dehydration, delirium and drowsiness. Sometimes a patient can get aggressive and this can be mistaken for terminal agitation. This is something we will look at in more detail in the Chapter 16.

Treatment is primarily by immediate rehydration using an intravenous infusion of normal saline over 24 hours. Once this is completed, medication called bisphoshonates will be started intravenously. The drugs used are either pamidronate or zolodronic acid. Bisphosphonates help to reduce bone resorption and lowered blood calcium can be seen after 2 to 3 days. Once a patient has had hypercalceamia, they can have repeated episodes that can occur close together. Application of the ethical principles we looked at on page 47 must be applied when re-treating a patient.

Remember, it is always important to treat the person, not the blood result.

The principles of evaluating care

Another useful model in supporting patients with complex symptoms is the ‘EEMMA’ model (Twycross et al 2009). This is a more complex model than the three Cs model, providing a comprehensive way of assessing, planning, administering and evaluating care from the perspective of the whole team, and is used extensively in many specialist palliative care units.

The EEMMA model

• Evaluation: looking at a patient’s story so far and includes considering what the cause of symptoms might be, the impact on the patient and what treatment has already been tried. Impeccable assessment is an essential part of the evaluation process.

• Explanation: considers what the patient and family understand about what is happening. Giving information and checking that the patient and family understand what is happening is an important part of ensuring they are fully involved in decision making.

• Management: this builds on the assessment process and looks at what symptoms are reversible. This is the first step and can be motivating to both the patient and family to see an improvement in symptoms, even if they are small.

• Monitoring: this is the responsibility of all team members. Noticing just a small change can have a big impact on the treatment plans. It is important to let patients know if there is a variety of treatment options available. This means that patients will not become disillusioned if medication or care intervention doesn’t work as they know there are more options.

• Attention: keep showing an interest in the patient’s story. It is always important to

focus care on their experience of events and this avoids assumptions being made. Remember to avoid using jargon or making an assumption about the impact of symptoms on a patient’s psychological wellbeing.

Ahlberg K., Ekman T., Gaston-Johansson F., Mock V. Assessment and management of cancer-related fatigue in adults. Lancet. 2003;363:640–650.

Burzotta L., Noble H. Providing psychological support for adults living with cancer. End of Life Care. 2010;4(4):9–16.

Clancy J., McVicar A.J. Physiology and anatomy: a homeostatic approach, third ed. London: Hodder and Arnold; 2009.

Doyle D., Hanks G., Cherney N., Calman K. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine, 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005.

Drudge-Coates L., Rajbabul K. Diagnosis and management of malignant spinal cord compression: part 1. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2008;14(3):110–116.

Drudge-Coates L., Rajbabul K. Diagnosis and management of malignant spinal cord compression: part 2. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2008;14(4):175–180.

Frith H., Harcourt D., Fussell A. Anticipating an altered appearance: women undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2007;11(5):385–391.

Hinsley R., Hughes R. The reflections you get: an exploration of body image and cachexia. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2007;13(2):84–89.

Holdcroft A., Power I. Management of pain. British Medical Journal.. 2003;326:635–639.

Holland K., Jenkins J., Solomon J., Whittam S. Applying the Roper–Logan–Tierney model in practice, 2nd ed, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingston, 2008.

International Association for the Study of Pain. Classification of chronic pain. Online. Available at: http://www.iasp-pain.org, 2007. (accessed June 2011)

Levack P., Graham J., Collie D. Don’t wait for sensory level – listen to the symptoms: a prospective audit of the delays in diagnosis of malignant cord compression. Clinical Oncology. 2001;14:472–480.

McCaffery M. Nursing practice theories related to cognition, bodily pain and main environment interactions. Los Angles: University of California Student Store; 1968.

McCaffery M., Pasero C. Pain: clinical manual, 2nd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1999.

Mock V., Atkinson A., Barsevick A., et al. Cancer related fatigue. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Fort Washington, PA: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology; 2005.

Morgan H., Cawley D. Recognising metastatic spinal cord compression and treatment. End of Life Care. 2009;3(4):15–21.

National Collaborating Centre for Cancer. Metastatic spinal cord compression: diagnosis and management of patients at risk of or with metastatic spinal cord compression. National Collaborating Centre for Cancer, London: Full guidance. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; 2008.

Nursing and Midwifery Council. The code: standards of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives. London: NMC; 2008.

O’Regan P., Hegarty J. Fatigue and depression in patients with advanced disease. End of Life Care. 2009;3(2):26–32.

Payne S., Seymour J., Ingleton C. Palliative care nursing: principles and evidence for practice, 2nd ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press; 2008.

Piper C. Assessment and management of the mouth at the end of life. End of Life Care. 2008;2(1):8–14.

Price B. Altered body image: managing social encounters. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 2000;6(4):179–185.

Ream E., Richardson A. Fatigue: a concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 1996;33(5):519–529.

Roper N., Logan W., Tierney A.. The Roper–Logan–Tierney model of nursing: based on activities of living, Edinburgh:Churchill Livingstone ;2000.

Salter M. Altered body image: the nurse’s role, 2nd ed, Edinburgh: Baillière Tindall, 1997.

Stannard S. Morphine: dispelling the myths and misconceptions. End of Life Care. 2008;2(3):7–12.

Stewart A. Clinical practice: hypercalcaemia associated with cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:373–379.

Stone P., Richardson A., Ream E., et al. Cancer-related fatigue: inevitable, unimportant and untreatable? Results of a multi-centre patient survey. Annals of Oncology. 2000;119(8):971–975.

Twycross R., Wilcock A., Stark Toller C. Symptom management in advanced cancer, 4th ed. Nottingham: palliativedrugs.com; 2009.

Uys L., Habermann M. The nursing process: globalisation of a nursing concept – an introduction. In: Habermann M., Uys L. The nursing process – a global concept. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2005.

National End of Life Care Programme in England and Wales – gives details of best practice tools and national initiatives, http://www.endoflifecareforadults.nhs.uk/ (accessed November 2011).

East Midlands Cancer Network education site for the public and professionals. Contains news of local initiatives, practice guidelines on symptom management, communication and breaking bad/significant news: http://www.eastmidlandscancernetwork.nhs.uk/ (accessed November 2011).

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), Recommends evidence-based practice for a wide range of illnesses. There is a large section on cancer and cancer treatments offering guidance for clinicians: http://www.nice.org.uk (accessed November 2011).